Citizen Smith

Thirty-six years as the gold-standard courtside tactician would have been plenty. The man hired to plug holes in a crisis brought Carolina and his community so much more.

by Beth McNichol ’95

Dean Smith is rightly remembered as a legend. But even that word, with all of its heft, is too tidy a term to capture what he meant to Carolina and to college basketball. He was an architect who took over a storied but scarred program and created an organism of confidence, fidelity and integrity that weathered more than three decades’ worth of enormous change in college athletics.

Over the course of the 36 years in which he created and delighted Tar Heel fans at home and around the world, the incomparable coach mastered the beautiful complexities of a simple game on the court and lived and taught his players the simple truths of a complex humanity away from it.

His passing on Feb. 7 at age 83 ended his fight against a progressive neurocognitive disorder, announced by his family in 2010, which had affected his daily activity and limited his formerly undaunted memory. He had retired from coaching in 1997.

Smith was a teacher whose pulse raced with as much excitement during practice as it did during games. He was a mentor to hundreds of players and coaches on the Carolina campus — and dozens off of it, too — who sought his advice on their own personal and professional lives. And he was an uncompromising believer in the freedom of men and women of every color and every background, and in their right to think, feel and act without the affront of prejudice.

Carolina Coach Roy Williams ’72 said: “It’s such a great loss for North Carolina — our state, the University, of course the Tar Heel basketball program, but really the entire basketball world. We lost one of our greatest ambassadors for college basketball for the way in which a program should be run. We lost a man of the highest integrity who did so many things off the court to help make the world a better place to live in.

“He set the standard for loyalty and concern for every one of his players, not just the games won or lost. He was the greatest there ever was on the court but far, far better off the court with people.”

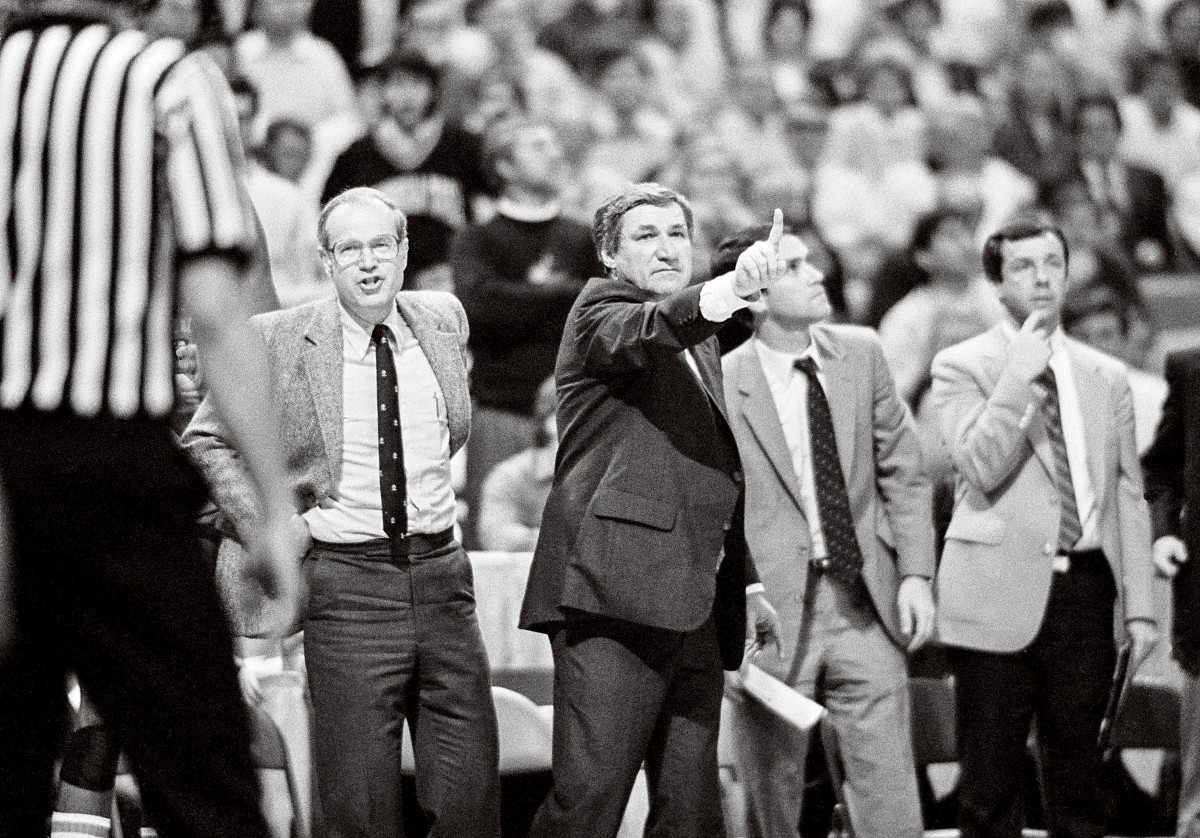

Bill Guthridge, who coached alongside Smith for 30 years and then took the reins of the program from him, said: “Dean was a great friend and a great coach. I will miss him dearly. He was devoted to me and I to him, and I will forever be grateful for our friendship.”

Eddie Fogler ’70 and Roy Williams ’72 are among many who left Smith’s nest to coach. Bill Guthridge tested the waters but wouldn’t leave. (Photo by Associated Press/Joe Sebo)

Retired with the most wins

Smith’s resume was as complete as any in sports. He broke Adolph Rupp’s all-time wins record in 1997 and finished with 879 victories, best among college basketball coaches at the time he retired. He amassed 20-win seasons for 27 straight years and in 30 of his final 31, a feat no other coach has ever matched. His teams collected two national titles; 13 ACC Tournament championships; 17 ACC regular season titles; 11 Final Four appearances and 23 consecutive trips to the NCAA tournament, with 27 appearances in all. He was named National Coach of the Year four times, ACC Coach of the Year nine times and taught five National Players of the Year and 26 All-Americans.

The coach traveled a long, frustrating and doubt-filled road to the March day in 1967 — not far from the spot outside Woollen Gym where he once was hanged in effigy — when Carolina fans showered him with love as the team departed for the Eastern Regional and, later, the Final Four. (Photo by Jock Lauterer ’67)

In 2013, Smith received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, an award that his wife, Linnea, accepted on his behalf from President Barack Obama at a White House ceremony.

“I don’t think people really know the depth of his intelligence,” said Phil Ford ’78 at the time of the award. “Coach Smith would have been great in whatever profession he chose, whether it be a politician or a banker or a scientist or a mathematician.”

Smith was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1983 and is a member of the international FIBA Hall of Fame, the N.C. Sports Hall of Fame, the Kansas Sports Hall of Fame and the College Basketball Hall of Fame. In 2006, he was named to the inaugural class of the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame along with James Naismith, Oscar Robertson, Bill Russell and John Wooden.

Smith also became the first recipient of the Mentor Award for Lifetime Achievement, given by the UNC Committee on Teaching Awards for “a broader range of teaching beyond the classroom.” In 1989, he received the General Alumni Association’s Distinguished Service Medal.

In 1976, he coached the U.S. Olympic team to the gold medal in Montreal.

Still, of all his accomplishments, the one that mattered most to Smith was family — his own (he was married to Dr. Linnea Weblemoe Smith ’76 (MD) and had five children, including three from his previous marriage to Ann Cleavinger) and his basketball family.

From the beginning, he sought to create an environment in which players and coaches trusted one another and comported themselves with selflessness, a team that was as character-driven and compassionate as it was athletic. The evidence was in the details: His players could signal to leave the game at any time for a rest, knowing they wouldn’t be punished and could return whenever they felt ready. Coaches and players — on the court and from the bench — knew to point to the passer to acknowledge an assist following a basket, for you can’t have one without the other.

And Smith solicited his players’ thoughts on the world around them away from the court, infusing in their coach-athlete relationship a mutual respect as remarkable as any of his defensive sets.

His great rival eight miles away, Coach Mike Krzyzewski, said in a statement: “Dean possessed one of the greatest basketball minds, and was a magnificent teacher and tactician. While building an elite program at North Carolina, he was clearly ahead of his time in dealing with social issues. However, his greatest gift was his unique ability to teach what it takes to become a good man. That was easy for him to do because he was a great man himself.”

“I wanted our players to be involved in the issues of the day and to feel they could talk freely about them to me,” Smith wrote in 2004 in The Carolina Way: Leadership Lessons From a Life in Coaching. “I was eager to know their opinions, so I often mentioned current events in individual meetings. … I rarely gave my own opinion; I would just try [to get him to talk] so [he] would feel he had the same freedom of expression as other students.”

‘My father died when I was 12 years old, and Dean Smith is the only father I ever had.’

Charles Scott ’70

‘To me, the presence of Charles Scott on the court for us was nothing to commemorate or remark on. It was simply past due. It should have happened, no more and no less.’

Coach Dean Smith

Having inserted himself into civil rights issues off the court, Smith knew road games would be tough on the superstar everybody called Charlie. The first black scholarship athlete at Carolina, Scott ’70 was a two-time All-American. The coach called him by his preferred Charles. (Photo by Rich Clarkson/Sports Illustrated)

In an era of coaching titans who routinely launched into jumping jacks on the sidelines, Smith’s controlled manner stood out. Although he was deeply competitive, he did not engage in cheap fuming at his players at the expense of teaching. He worked to understand the men he coached. In the voluminous annals of Carolina history, he became Chapel Hill’s most famous surrogate parent.

“When they introduce Coach Smith’s family, why don’t they say my name?” asked Carolina’s first black scholarship athlete, Charles Scott ’70, when Smith received the University Award in 1998. “My father died when I was 12 years old, and Dean Smith is the only father I ever had.”

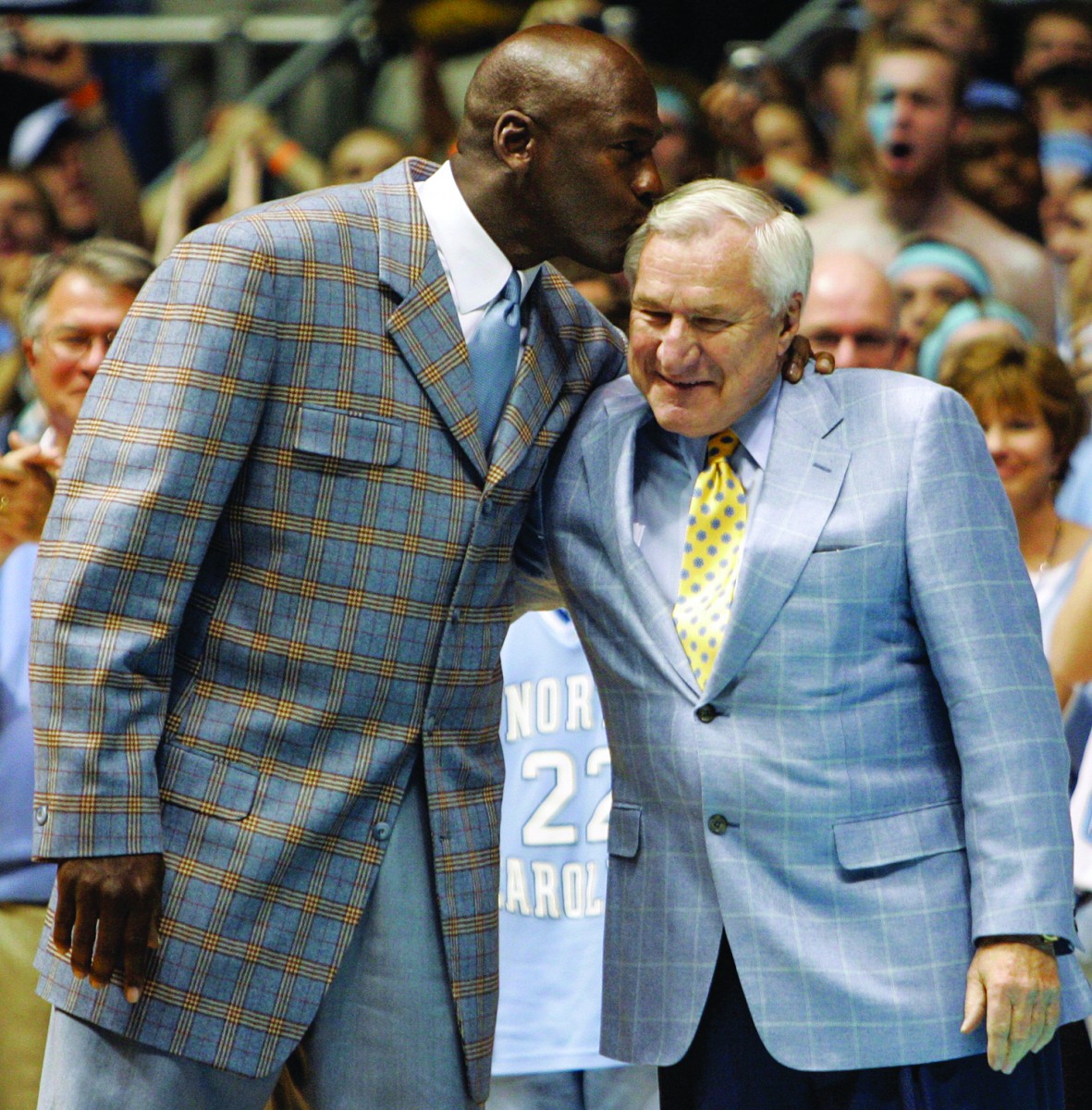

‘Thanks, Pops, for all the advice, all the education. … There’s no way you guys ever would have gotten to see Michael Jordan play without Dean Smith teaching me.’

Michael Jordan ’86, recalling what he was thinking when he planted a kiss on Smith’s head during a 2007 celebration for Smith

Many fans wonder what would have happened if Smith had unleashed Michael Jordan ’86 from his rigid system. At a reunion of the players from championship teams in 2007, Jordan personified the loyalty Smith shared with Carolina players, during and after their time in Chapel Hill. (Photo by Associated Press/Gerry Broome)

When another peerless basketball figure, six-time NBA champion Michael Jordan ’86, planted a kiss on Smith’s head at a celebration of Smith’s two national titles in 2007, Jordan recalled what he was thinking at the time: “Thanks, Pops, for all the advice, all the education.”

“The man he made out of me, in addition to my parents, and the basketball skills he elevated to another level …,” said the player who sank the jumper that gave Smith his first national championship, against Georgetown in 1982. “There’s no way you guys ever would have gotten to see Michael Jordan play without Dean Smith teaching me.”

‘Each person with dignity’

Born Feb. 28, 1931, Dean Edwards Smith grew up a Baptist son in Emporia and Topeka, Kan., with teacher parents. His father, ?Alfred, was a high school basketball coach who integrated the all-white Emporia High team in 1934, 32 years before the younger Smith would recruit Charlie Scott to Chapel Hill to do the same.

Smith greeted Scott’s presence on the Carolina team in 1966 with the same inconspicuous conviction that he learned from his father, “a fundamental understanding that you treated each person with dignity.”

“To me, the presence of Charles Scott on the court for us was nothing to commemorate or remark on,” Smith said. “It was simply past due. It should have happened, no more and no less.”

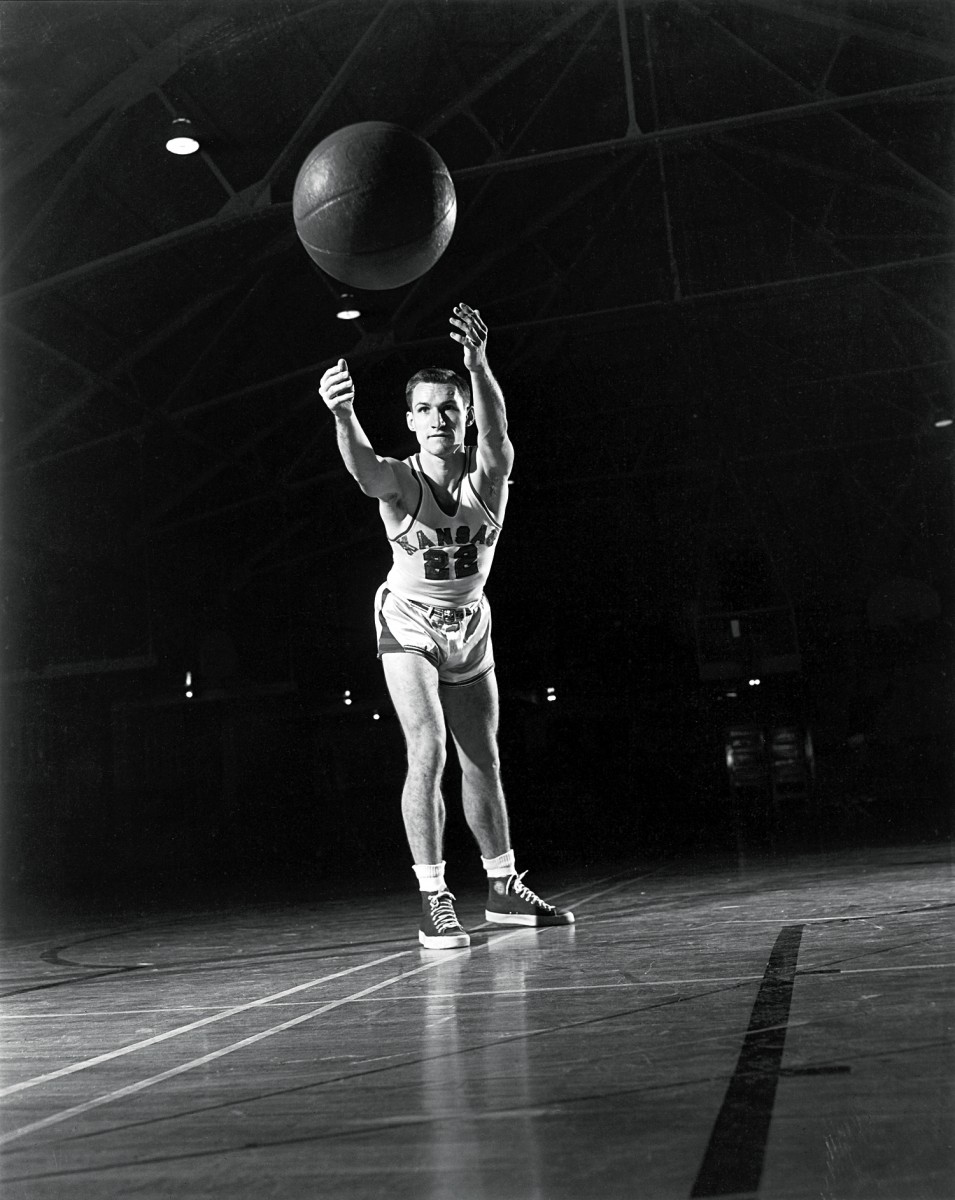

A publicity shot of the Kansas player seems to portend his philosophy that nobody was bigger than the game (and that the pass can be as important as the shot). (Photo by Rich Clarkson/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images)

Smith competed in football, baseball and basketball at Kansas, where he was in the Air Force ROTC. ?A mathematics major, he played guard on the Phog Allen-coached 1952 national championship team for the Jayhawks, who also were national runners-up the following year, his senior season.

He was an assistant coach at the Air Force Academy when Frank McGuire first asked him to be his No. 2 in Chapel Hill; the brash New Yorker posed the question to Smith over breakfast the morning after the 32-0 Tar Heels had defeated Smith’s beloved Kansas in an epic triple overtime contest to win the 1957 NCAA title.

The loss had stung Smith badly, but the job offer was more warmly received.

The next year, he came to UNC for good. From the moment he first set foot in Chapel Hill on an April day in 1958, “with dogwoods and cherry trees in blossom and petals floating in the breeze and dusting the footpaths,” as he wrote in his biography, Smith was in love with the town and the University.

‘I’ll support you. Don’t worry about the winning and the losing.’

UNC Chancellor William Aycock ’37, reassuring Smith during the tough early years

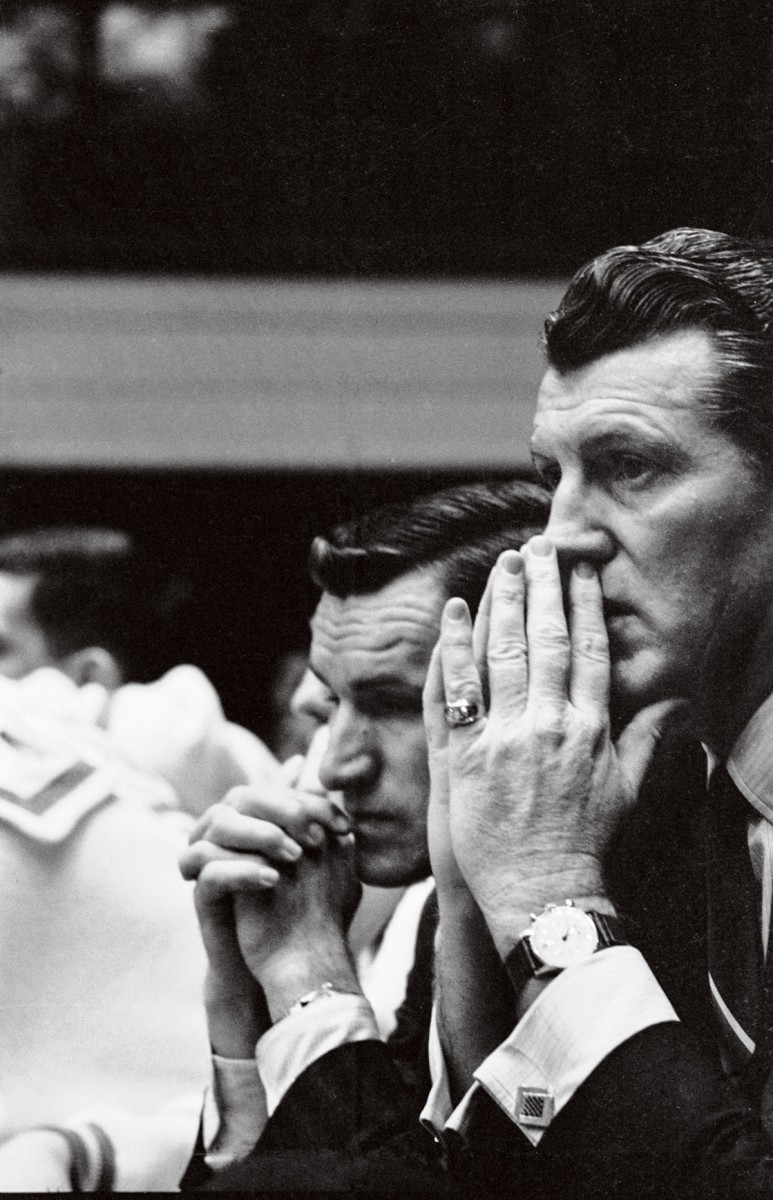

Frank McGuire was stylish, brash and, soon, in trouble. His assistant, quiet and analytical, was sent in to clean up the Carolina program. (Photo courtesy of the Hugh Morton Collection)

UNC Chancellor William Aycock ’37 (MA, ’48 JD) soon would come to learn the value, and values, of the young Kansan. In 1961, Smith helped Aycock sort the facts behind the Tar Heels’ NCAA violations over excessive entertainment spending, which resulted in sanctions that included a postseason ban and probation. McGuire, asked to change his extravagant ways by Aycock, resigned that year, prompting Aycock to elevate his 30-year-old assistant to head coach — the only person he bothered considering.

Aycock told Smith: “I’ll support you. Don’t worry about the winning and the losing.” The two built a friendship bolstered by a shared belief that victories were secondary to the journey, a concept that might seem more a quaint ideal than a doable mantra in the modern athletic landscape.

But over more than three decades, Smith’s teams never came under NCAA scrutiny. The fact that he kept his program’s integrity intact while amassing a .776 winning percentage, graduating a staggering 96 percent of his athletes and preparing more than 50 future ABA and NBA players was a dividend Aycock could not have foreseen.

Smith’s early tenure was not without its grumblings. His hanging in effigy by Carolina fans during the 1965 season, following an ugly 22-point loss — the team’s fourth straight defeat — was a scar in the program’s history that bothered others more than it bothered Smith. His teams answered thereafter by winning, and winning regularly.

Smith rarely let the public see his practices, but with the Four Corners, what was the difference? Opponents seldom were able to do much to counter it. The late-game strategy was made for Phil Ford ’78, and he for it. (Photo by Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images)

Tar Heels rising

The three-year run beginning with the 1966-67 season that saw the Tar Heels win three consecutive ACC regular season and tournament titles and make three straight trips to the Final Four was the beginning of Smith’s long string of excellence on the court. This was when Smith’s Four Corners offense, later eponymous with the gifted point guard Phil Ford ’78, first appeared in Carolina blue. Although the delay game — and the introduction of the shot clock it caused, in 1985 — became the strategic imprint for which he was best known, he was an innovator on defense as well. His 1981 book, Basketball: Multiple Offense and Defense, became the all-time best-selling technical book about the game.

Even as success bloomed in Chapel Hill, Smith kept the game in perspective when it mattered most. He allowed his players to lend their weighty, well-known voices to causes they believed in, such as when Bill Chamberlain ’72 asked to miss practice to attend a rally for UNC cafeteria workers fighting for higher wages in 1968.

“He stood on solid footing, whether it was popular or not,” said Eric Montross, shown here with Smith at the ACC Tournament in 1994. (Photo by Bob Donnan /Sports Illustrated/Getty Images)

“We’re human beings first, coaches and players second, and in the ’60s we had to strike an extremely delicate balance between the two,” Smith wrote. “Sometimes there was a dichotomy at work. But I was aiming to show our players that there was nothing wrong with that because complexity is part of life. There is something to be said for having your own convictions and views and your own way of living, regardless of your vocation.”

Years before, while Smith was still an assistant coach at Carolina, his pastor at Binkley Baptist Church, Robert Seymour, asked Smith to dine with him and an African-American student at The Pines restaurant at a time when Chapel Hill had not yet integrated its eateries. Seymour felt The Pines would have no choice but to seat them with Smith in the party; the basketball team and McGuire were regular patrons. Smith agreed, and the trio was seated without incident.

Smith often bristled at suggestions that he had been a pioneer in civil rights; when a reporter told him that he should be proud of his role in integrating Chapel Hill institutions, he dismissed the assertion as supercilious.

“You should never be proud of doing the right thing,” he said. “You should just do it.”

Smith took seriously the “human family” that his father taught him to value, speaking out against issues that moved him. He was against nuclear arms; opposed a state lottery that he believed would prey on those in poverty; and took his teams to visit prisoners, a symbiotic gesture meant to lift both groups up in gratitude. Steered by a deep faith, he adamantly disagreed with capital punishment, sometimes phoning death row inmates in the hours before their executions to let them know he would remember them.

He lived a life he believed in, while he coached a game he loved.

“To me, the players got the wins, and I got the losses,” he said. “Caring for one another and building relationships should be the most important goal, no matter what vocation you are in.”

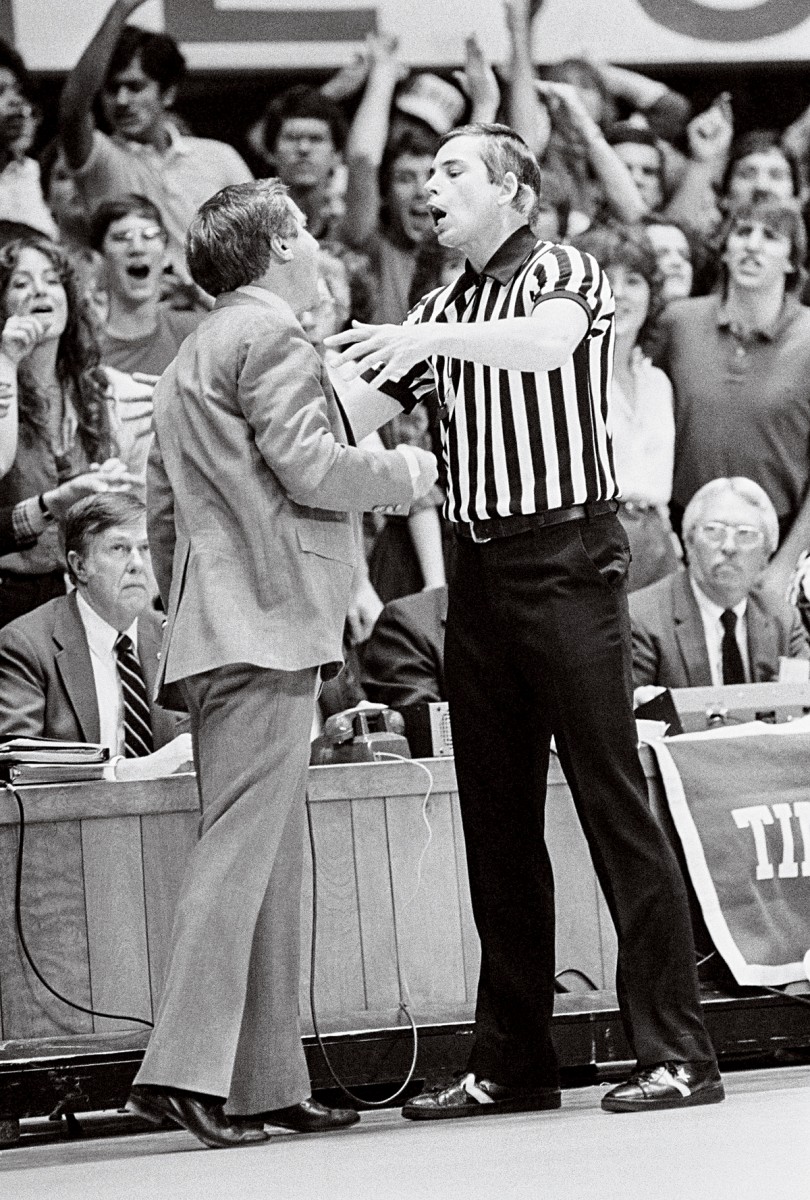

“Sit down, Dean!” Smith was a master at working the referees, which often stemmed from fierce protectiveness of his players. Some opposing coaches thought his behavior gave the lie to the clean-cut image he liked to portray. Sometimes when he appeared to the TV viewer to be addressing his team, he really was screaming at the ref. (Photo by Associated Press/Bob Jordan)

‘Are you having fun?’

He believed in comebacks, too. They were a cross-generational art form under Smith, whether the Tar Heels (and Walter Davis ’77) were demoralizing Duke after being down eight with 17 seconds to play (1974); or steamrolling back against Florida State, outscoring the Seminoles 28-4 over the final nine minutes (and cutting a 21-point lead to four in just two and a half minutes) during Smith’s sparkling, second national championship season (1993). Those contests were gifts with giant Carolina blue bows for college basketball fans, who delighted in the ride whether in the stands or on their couches.

And they were some of Smith’s favorite moments, too. In the midst of the excitement, his timeouts were never just about X’s and O’s. They were about reassuring 12 young men that they had prepared exhaustively for whatever may come. So in a close huddle and closing in on an otherwise improbable win, with a raucous excitement from the crowd echoing in his ears, Smith often would look at his players and say four words that reminded them why they play the game, and why Smith himself had decided to become a coach.

On his way to the showers after being ejected from the 1991 national semifinal, Smith paused to congratulate the Kansas players who would wind up sending the Tar Heels home prematurely. He often wrote letters of praise to worthy opponents, but woe be to those he thought had roughed up his players. (Photo by Bob Donnan/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images)

“Are you having fun?” he would ask, grinning.

We all were. The era belonged to a man too selfless to claim it as his own, and that made it all the more sweet, a kind of baby blue lightning in a bottle. Those 879 wins will always belong to Coach Smith. His loss belongs to the rest of us.

“One of the striking things about my profession,” Smith wrote, “is that not many coaches retire on their own timetable. Most of us were not that lucky. I was. Again, thanks go to my players. I do remember all of them.”

Beth McNichol ’95, a freelance writer based in Raleigh, is a former associate editor for the Review.

‘One of the striking things about my profession is that not many coaches retire on their own timetable. Most of us were not that lucky. I was. Again, thanks go to my players. I do remember all of them.’

Coach Dean Smith

Once criticized for a style not conducive to winning the big one, Smith took “time out” to cut pieces of the net for the Heels who won him his second national title against Michigan in 1993. With the lean years included, his teams went to the NCAA tournament 27 times in 36 years. (Photo by Scott Sharpe ’83/The News & Observer)

More stories about Dean Smith

- “Long Ago He Won the Big One: Dean Smith’s best victory,” by Frank Deford in Sports Illustrated

- “A Credible Saint: How Dean Smith Became North Carolina’s Moral Compass,” by Will Blythe ’79 in To Hate Like This Is to Be Happy Forever

- “An appreciation of Dean Smith’s life,” by John Feinstein in The Washington Post

- “The Relentless Scrimmage in Dean Smith,” by Gary Smith in Inside Sports

- “Dean Smith: Ties That Bind,” Matt Morgan ’05 in Inside Carolina

- May/June 1997 Review: “Coach,” by David E. Brown ’75 commemorating Smith’s 877th win, and “Carolina’s Dream Team,” column by Doug Dibbert ’70, about how Coach Smith will always be proudest of his players’ graduation rate

- November/December 1997 Review: “About the Players,” by David E. Brown ’75 just after Smith’s retirement

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.