From Video Store to the Oscars

Posted on Sept. 15, 2020

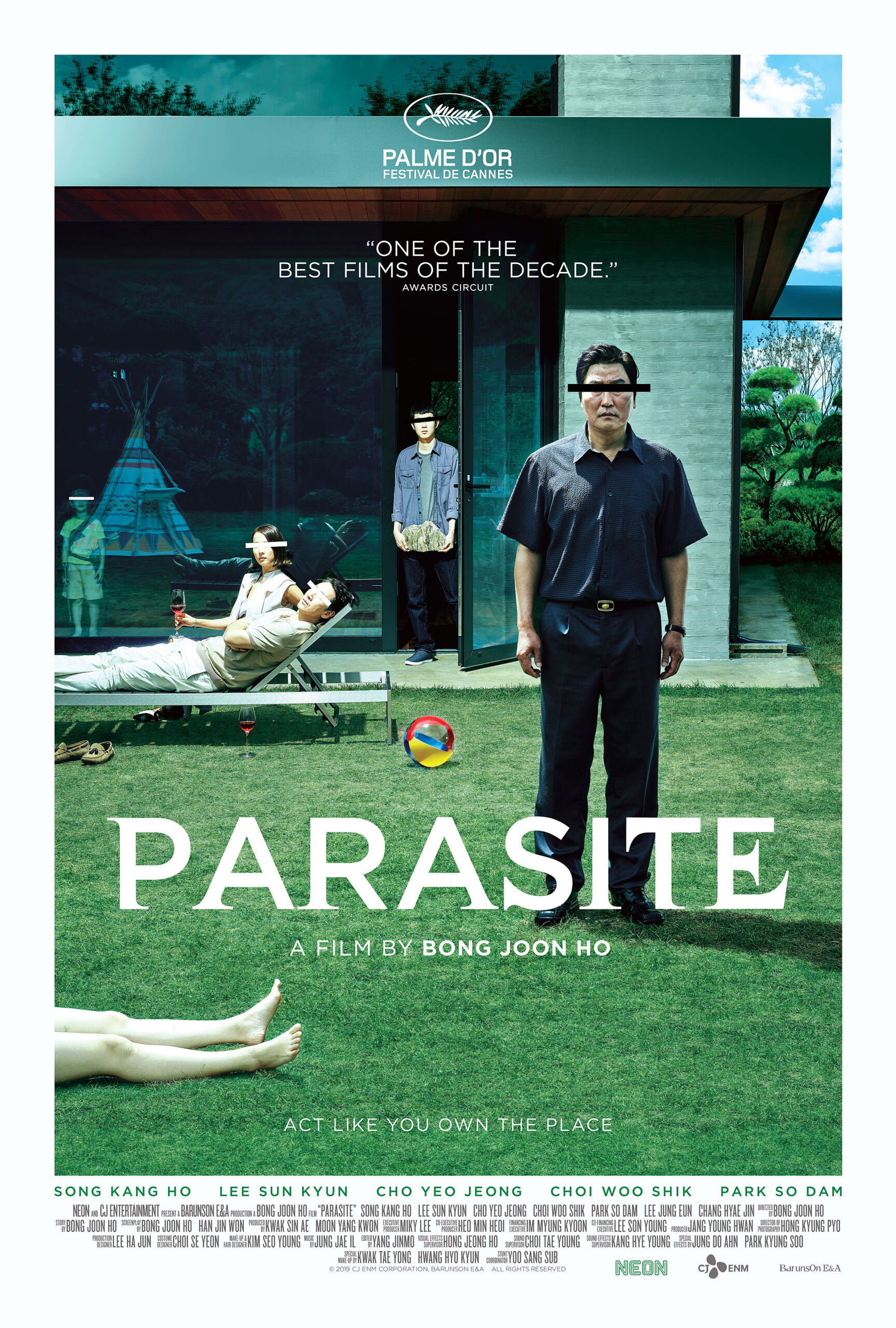

Tom Quinn ’93 has championed directors such as Bong Joon Ho, whose Parasite this year became the first non-English language film to win the Academy Award for best picture. (Photo by Michael Kovac/Getty Images for NEON)

When Parasite became the first non-English language film to win the Academy Award for best picture this year, the spirit of Chapel Hill’s VisArt Video hovered inside the Dolby Theatre in Los Angeles like a house ghost at Hogwarts.

Tom Quinn ’93 — founder and chief executive officer of film distributor NEON and a key driver in the genre-bending movie’s journey to Oscar history — credits his college gig at the now-defunct video rental shop with introducing him to the magic of film.

In the decades since that part-time job, the once-aspiring actor rose to prominence in the independent film industry, developing a knack for recognizing consumer tastes while ushering the art of directors like Parasite’s Bong Joon Ho to the masses. Since 2013, when he was president of The Weinstein Company’s boutique label Radius, Quinn has released films that have garnered 16 Academy Award nominations and seven wins, including back-to-back best documentary champions 20 Feet From Stardom and Citizenfour.

Launching NEON in 2017, Quinn was determined to show that small-budget films deserved a distribution plan wider than the living room couch. He had immediate success, beating out Netflix to acquire I, Tonya, which snagged a supporting actress Oscar for Allison Janney. Then came the lightning bolt that was 2019, in which films like Apollo 11, Three Identical Strangers, the critically lauded Honeyland and, of course, Parasite, established NEON as the company small enough to find auteur gems and big enough to expand the boundaries of film’s influence.

Launching NEON in 2017, Quinn was determined to show that small-budget films deserved a distribution plan wider than the living room couch. He had immediate success, beating out Netflix to acquire I, Tonya, which snagged a supporting actress Oscar for Allison Janney. Then came the lightning bolt that was 2019, in which films like Apollo 11, Three Identical Strangers, the critically lauded Honeyland and, of course, Parasite, established NEON as the company small enough to find auteur gems and big enough to expand the boundaries of film’s influence.

Quinn was born in Greenville and raised internationally. His father, Tom Quinn Sr., coached the East Carolina men’s basketball team from 1965 to 1974 before moving the family overseas, where he coached professional teams and later led the United Arab Emirates national team. The younger Quinn dreamed of being a basketball player himself, until reality set in that he “was not gonna be as tall as my hero, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.”

His fallback career choice — discovering gifted directors and sharing their work with film-lovers everywhere — isn’t too shabby.

“Any complaints that anybody would make about working in film,” he said, “it’s a high-class problem.”

Quinn spoke to the Review in May from his home in Los Angeles, where he was riding out the pandemic that had shuttered theaters by planning new ways to bring the communal spirit of cinemas to socially distanced audiences. Among them: vintage drive-in theater premieres and pop-up cityscape screenings that project films across buildings, allowing viewers to watch from apartment windows. In June, NEON donated $250,000 to Black Lives Matter organizations and turned its focus to screening its catalog of films created by Black artists.

Many of us have been inside for months, predominately watching life unfold on small screens. Meanwhile, the outside world grows exponentially more complicated each day.

Yeah. And I’m not doing a particularly good job of making sense of it. The days are endless. And marked by maybe caffeine meltdowns and alcohol. [laughs]

That drives home the point that we still need shared stories — real and imagined — to help process what’s happening. How do you achieve that collective experience during a pandemic?

We’re doing things we’ve never done before. NEON’s whole ethos is built on the power of cinema, and it only exists in theaters. The shutdown has clearly delineated that. There’s no such thing as virtual cinema; cinema is a precious, sacred thing that is born out of live theater, which is what I spent most of my time doing at UNC. So the more you can do to create that live experience, as if it’s only happening there and then, the more you can still create what makes it special. In great movies, sometimes audiences are the best characters in the film. That one night, that one showing, is an opportunity to create that.

You moved to Los Angeles after Chapel Hill and began to build a career that you had not planned for — from scratch. How did you go from aspiring stage actor to film executive?

Within two weeks of being in LA, I realized that I just didn’t like the industry of acting, wasn’t a huge fan of my fellow actors, and that I wasn’t a particularly good kiss-ass and wasn’t going to get far. The other young actors I met had a criminal amount of confidence they were going to make it, and I did not. [laughs] The amount of integrity you had to leave by the wayside to make it … it just wasn’t for me. So I had to find something else. Luckily, I got a temp job for the head of publicity at Samuel Goldwyn and stuck around.

Slowly but surely, I charted my way. It took me 25 years to get here, but it was pretty methodical. And I was very stubborn. At first, I wanted to get a job where I could get paid to watch movies. That’s acquisitions. Then I wanted to get paid to learn how to distribute films. And I wanted more of a say in what we did as a company, so I started my own label [at Radius]. And then I wanted to have real equity and full decision-making power over everything we did, so I created my own company with NEON. It’s been four very, very long-winded steps to get there, but it’s been a really fun ride.

You’ve said that your college job with VisArt helped you develop a keen eye for films others might miss, like Honeyland or Parasite. Tell us about that love affair.

I mean, VisArt was an institution, you know? Known nationally, had every possible film you could ever imagine. I worked there for a little over a year. We were allowed to rent six movies a day, and I did. I found myself falling in love with foreign-language films that, even though I had lived overseas, and even though I spoke multiple languages, had never been a part of my upbringing. Without VisArt, I don’t know that I would be working in film.

Is it true that when you are screening movies at festivals, you have to leave the theater sometimes because you get emotional?

Yeah, I get really passionate. I cry. I laugh at really awkward moments. I am a very engaging audience member. And the nerves that set in immediately thereafter of, “How am I gonna get this movie? It’s going to be so wildly competitive.”… And then the heartbreak of not getting it. …

I’ve been delusionally wrong, too. Some films that I absolutely adore crash and burn. I’m lucky that I’ve been more successful than not. But at some point, that may not be the case. That’s the fun in building your own company is others embracing that vision and seeing them go out and find the films that drive them the way that Parasite drives me.

Before you started NEON, you had worked with director Bong Joon Ho on his earlier movies — The Host, Mother, Snowpiercer. Is that why you bought the rights to Parasite before a single frame had been filmed?

I’ve been a fan of his for so long, so I’m not objective. I’m not anything but a champion of who I believe to be the world’s greatest filmmaker. The hope at NEON was always that we were gonna work with Bong when and if a film of his became available, and so it was, and we did.

You have to go with your instincts, and at some point, if it doesn’t work, at least you’re left with the belief that you are consistent about what you want to be a part of. Our whole team is invested in the same philosophy that cinema is everything. And setting a very high bar for ourselves about how we produce and distribute those films, and the filmmakers we want to work with — it is everything. My favorite thing that people asked me after the Oscars was, “Well, what are you gonna do now? Doesn’t this change everything?” I was like, “No, that was the point. This is what we’re doing, and we’re not going to change a thing.”

For those of us who are not in the film industry, put the Parasite win in context. What did it mean for Hollywood?

I mean, it upended paradigms that have been in place since the beginning of time. [laughs] The film deserved it. Multiple nominations, not a shock, and Bong had earned it for an exceptional film. But to win best picture was definitely an incredible result, not something that I could say, “Yes, I knew it.”

And it was great validation for me and all my friends who’ve been on these fool’s errands supporting our favorite filmmakers, on tours all over the world, for small foreign-language films, documentaries, whatever it may be. We broke the pattern and went all the way. Why can’t another film do the same? At the Oscars that evening, anything was possible. Cinema looked more powerful than ever going forward.

Anything was possible, and yet anything was possible except exactly this. [laughs]

Speaking of the pandemic: How do you adjust to the uncertainty after such a successful year?

It was exciting to move past the point of being a startup, of working through what they call the “trough of sorrow,” the graph where everything just sort of dips low and you don’t know how you’re going to make it from one quarter to the next. But then it all came together in this beautiful year of so many awesome films. And so now we get to think about the future. And it’s been accelerated and compounded by this quarantine, but … with so much uncertainty, I felt the least that we could do is let’s keep doing our job. Let’s keep bringing new films to audiences and not get paralyzed by this moment.

We can’t change the world. And on a good day, we enlighten and entertain. Even if we only distract, it’s a contribution we should stay committed to. The idea of not bringing new movies to the marketplace, even without the benefit of theaters and cinemas … that, to me, seemed more unfathomable than the situation we’re in now.

— Beth McNichol ’95

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.