Artist of the Portrait

Life often was a struggle for Bayard Wootten, and for many of her subjects, as she pursued early 20th-century photography on her own terms.

The north-facing windows above 142 E. Franklin St. were modified, long ago, to let in maximum light. It was the photography studio where Mary Bayard Morgan Wootten imagined and experimented — and also trudged through just getting the bills paid.

Bayard Wootten: “Anything necessary to get a picture.”

She was a businesswoman by necessity but an artist at heart. She started taking pictures just as the picture-takers’ first interpretive movement was peaking and starting to wane, and she just kept going, sticking to what was known as pictorialism as if she hadn’t heard the news. Just being “she” was challenge enough in a male-dominated field. Though gone now for 57 years and no longer a familiar name, she was a prominent figure about Chapel Hill at the height of her career in the 1930s.

Her meticulously composed images of people and of landscapes make her as important as any photographer to the preservation of the way North Carolina and the South looked in the early 20th century.

Her spirit is captured in the opening words of the book Jerry Cotten wrote about her 18 years ago: “Stop the car!” Speaking to her driver, she’d spotted something she must have on film. Bayard (BY-ard) Wootten would climb, crawl and swim to the vantage point she favored; she’d wait for hours until a cloud formation framed her subject just the way she wanted; she patiently talked a good picture out of Appalachian mountain people who often were suspicious.

“When photography started up about 1839 or so, and going up until the late 1800s, most people who practiced it were tradesmen,” said Cotten, who was the photographic archivist in Wilson Library for more than 30 years. “Toward the end of the 1800s, some photographers wanted to elevate it to an art form similar to painting. They started to incorporate features of painting into their photographs” in the choice of subjects and in techniques such as retouching negatives, even manipulating the composition.

“It peaked around 1910, and a lot of photographers who had embraced that movement gravitated to a more realistic style — they stopped trying to emulate painting.”

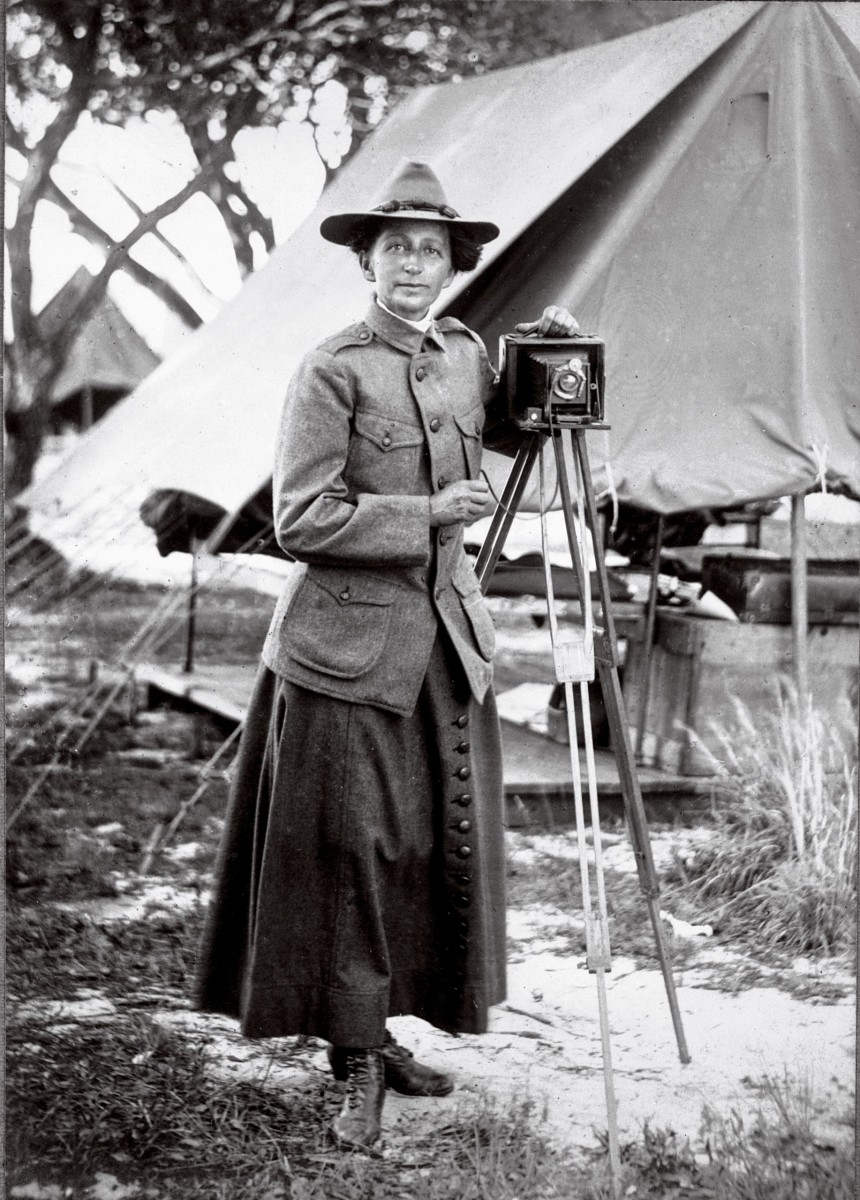

Wootten while working at Camp Glenn in Morehead City, ca. 1914.

Bell Tower, ca. 1931.

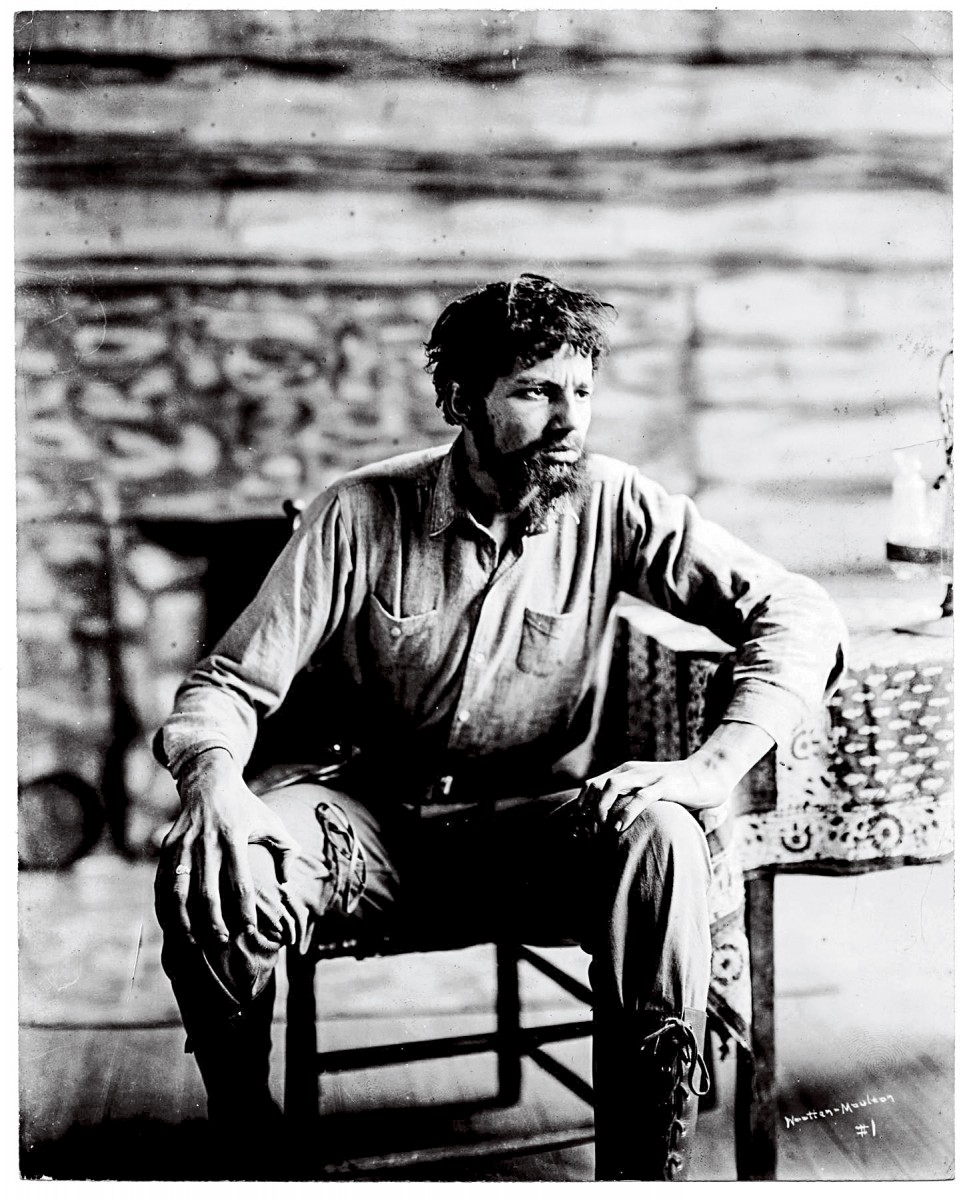

Thomas Wolfe ’20 in the PlayMakers’ The Return of Buck Gavin, Chapel Hill, 1919.

Wootten was born in a New Bern house with a view of the Neuse River, and though there was a touch of aristocracy in her family, it was not accompanied by money. She would never be more than comfortable financially, and at her death in 1959 she depended on family to care for her most basic needs.

Her 1897 marriage to Charles Wootten was over in 1901, apparently when he discovered the absence of money he’d counted on. With two children in tow, she never remarried.

Wootten took to painting flowers and other images on anything that would sell — greeting cards, calendars, china. As a graphic artist living next door to the man who invented Pepsi-Cola, she is believed to have drawn the company’s first logo.

She was first attracted to the camera just after the turn of the century, as innovations in photographic processes transformed picture taking from a simple trade to an art form. She pursued her art with abandon, but she also recognized the practical necessity of making a living. She hit upon the idea of the natural market for postcards among soldiers in a military camp and pursued it first at a National Guard camp in Morehead City and later at the fledgling Fort Bragg. Brushed off at first by officers, she later was given a military uniform and set up a studio at Bragg.

Sand dunes, North Carolina, 1930s.

Net fishers, Ocean Drive, South Carolina, 1930s.

Horse traders, Bryson City, 1930s.

The business lasted for 16 years, and it got Wootten noticed. Frederick Koch, UNC drama professor and founder of the Carolina PlayMakers, engaged her as the troupe’s photographer. She began a 26-year stint as the Yackety Yack’s photographer in 1921 and opened a Chapel Hill studio with her half-brother, George Moulton, in 1928.

Wootten’s signature work was yet to come.

A tobacco farmer and his three sons, North Carolina, 1930s.

An old home, Murrells Inlet, S.C., ca. 1937.

Tobacco workers at the barn, 1930s.

A woman at rest, Murrells Inlet, S.C., 1930s.

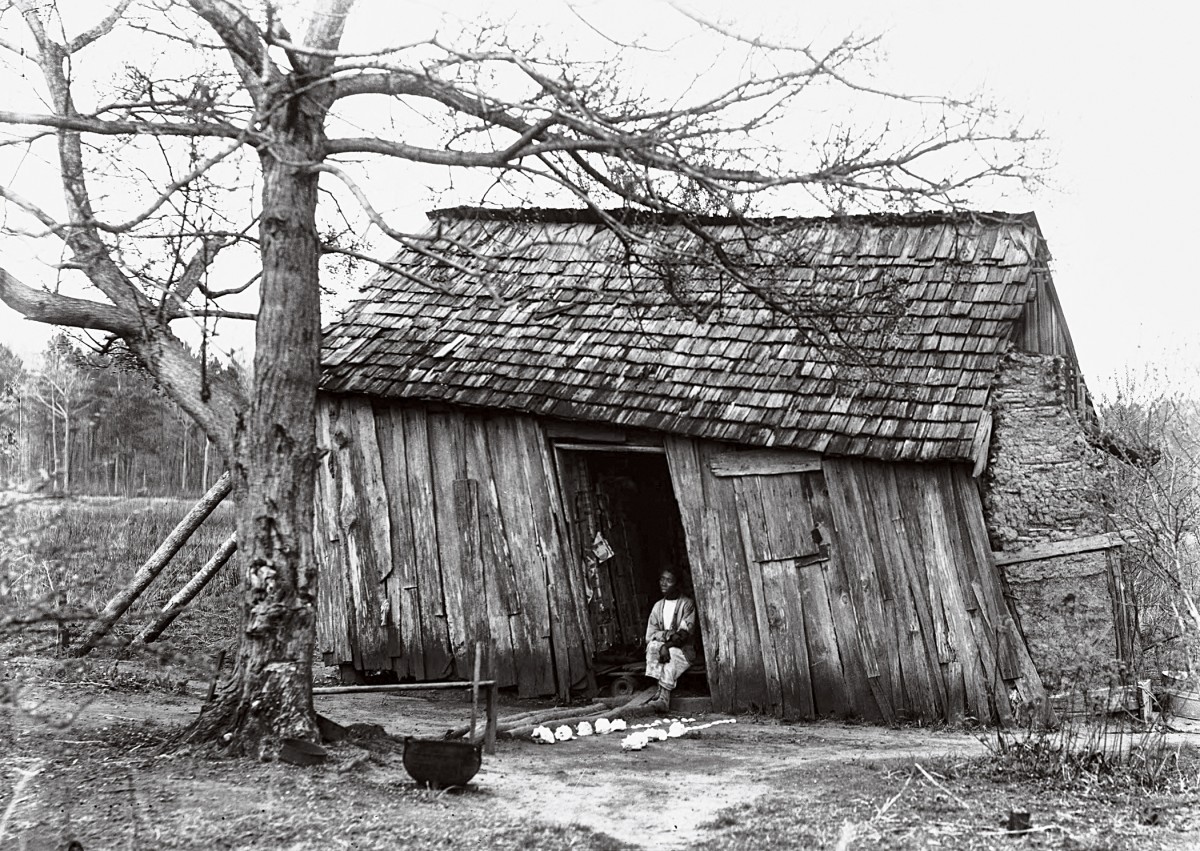

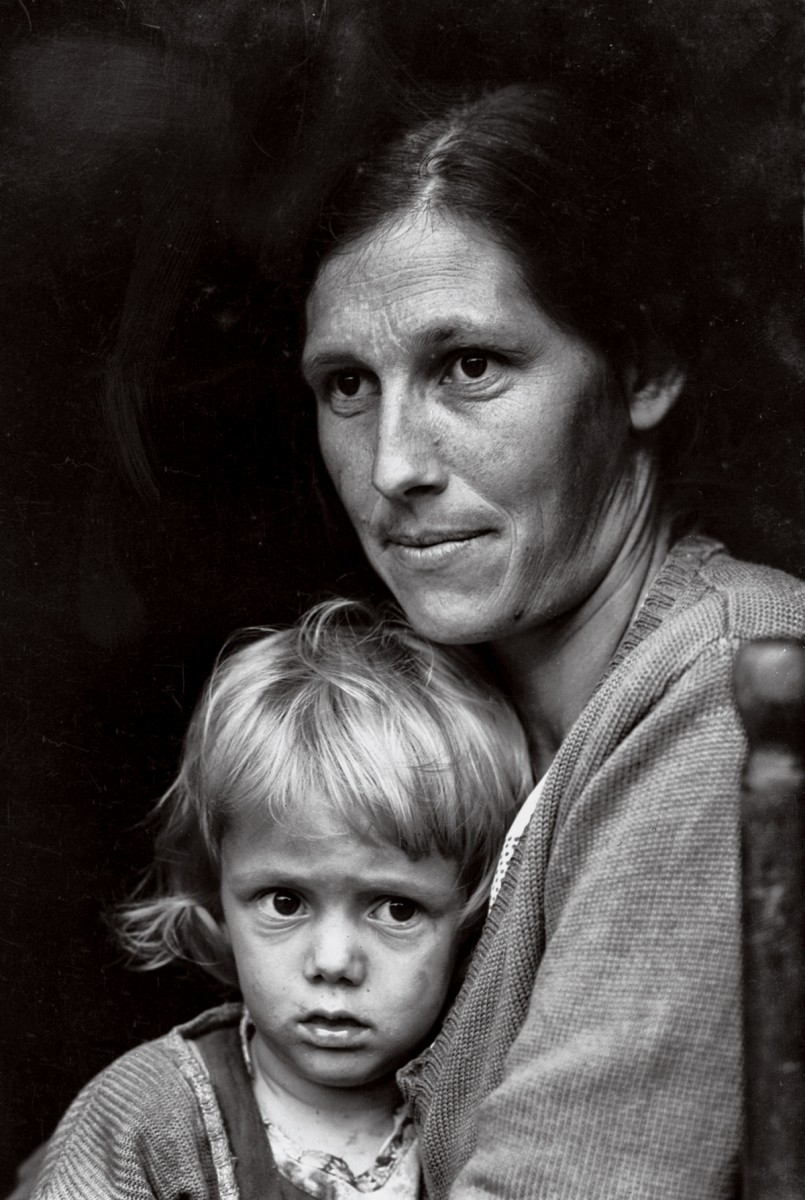

In the late 1920s, she took an invitation from her cousin, Lucy Morgan, to visit her at the Penland School of Crafts in the North Carolina mountains. That was the first of many visits and the springboard to Wootten’s wanderings on the backroads of the Southeast during the Depression, photographing landscapes and, in the faces of the people, rural struggle.

Cotten is convinced it was her best work. It caught the eye of Terry Crouch, director of the UNC Press, who used Wootten’s photographs to illustrate two Depression-era documentary books, Backwoods America and Cabins in the Laurel. Her extensive work in Southern gardens was featured in other books.

Eventually, her photographs were exhibited in the South and in Chicago, Boston and New York.

“The camera is not a free agent as brush or pencil,” she told a newspaper in 1926, “but relentlessly records things as they are. So the artist must bring to her aid strong contrasts of light and shade, artistic groupings and rhythmic lines. To use a camera as a means of artistic expression, a certain quality of spirit must be brought to aid light and air.”

— David E. Brown ’75

An exhibit of the architectural photography of Wootten and Frances Benjamin Johnston, both of whose work helped launch the architectural preservation movement in North Carolina, is in Wilson Library through Jan. 31. UPDATE: This exhibit has been extended through Feb. 7.

The library’s North Carolina Collection has more than 90,000 images Wootten and her studio created; dozens of them can be seen at alumni.unc.edu/wootten.

Mrs. Will Carpenter, Penland, 1930s.

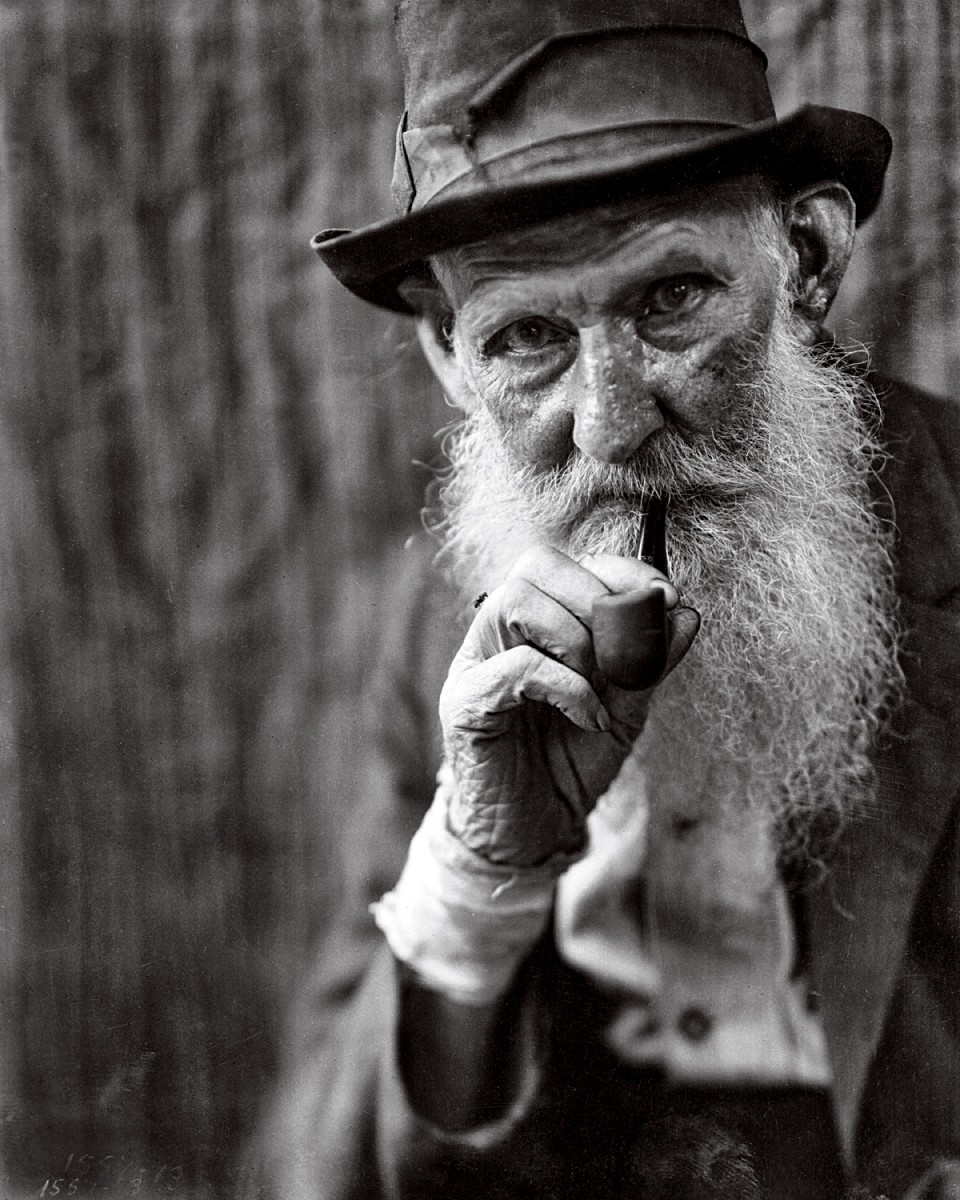

Tom Sparks, Mitchell County, ca. 1934.

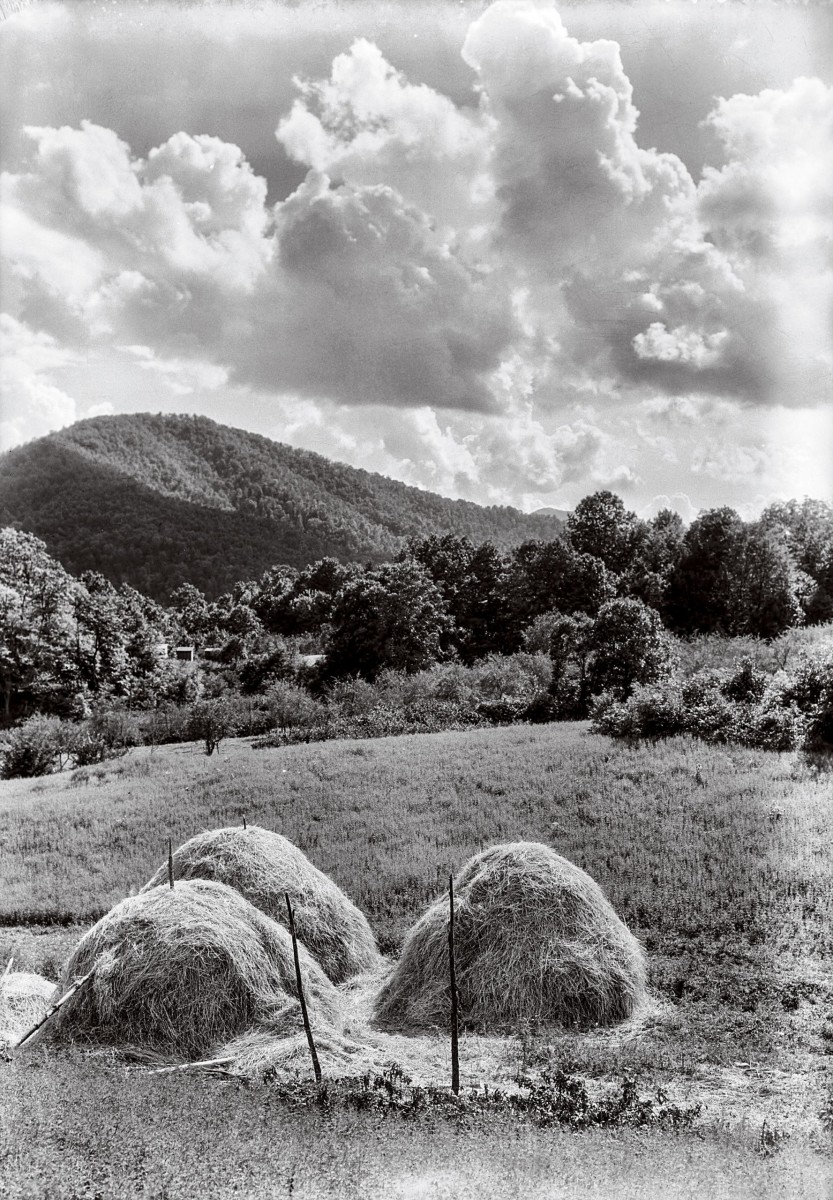

Baileys Peak, North Carolina.

Cabin, Mitchell County, 1930s.

Group in a window, western North Carolina, 1930s.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.