In Memoriam: C.D. Spangler Jr. ’54

Posted on July 23, 2018

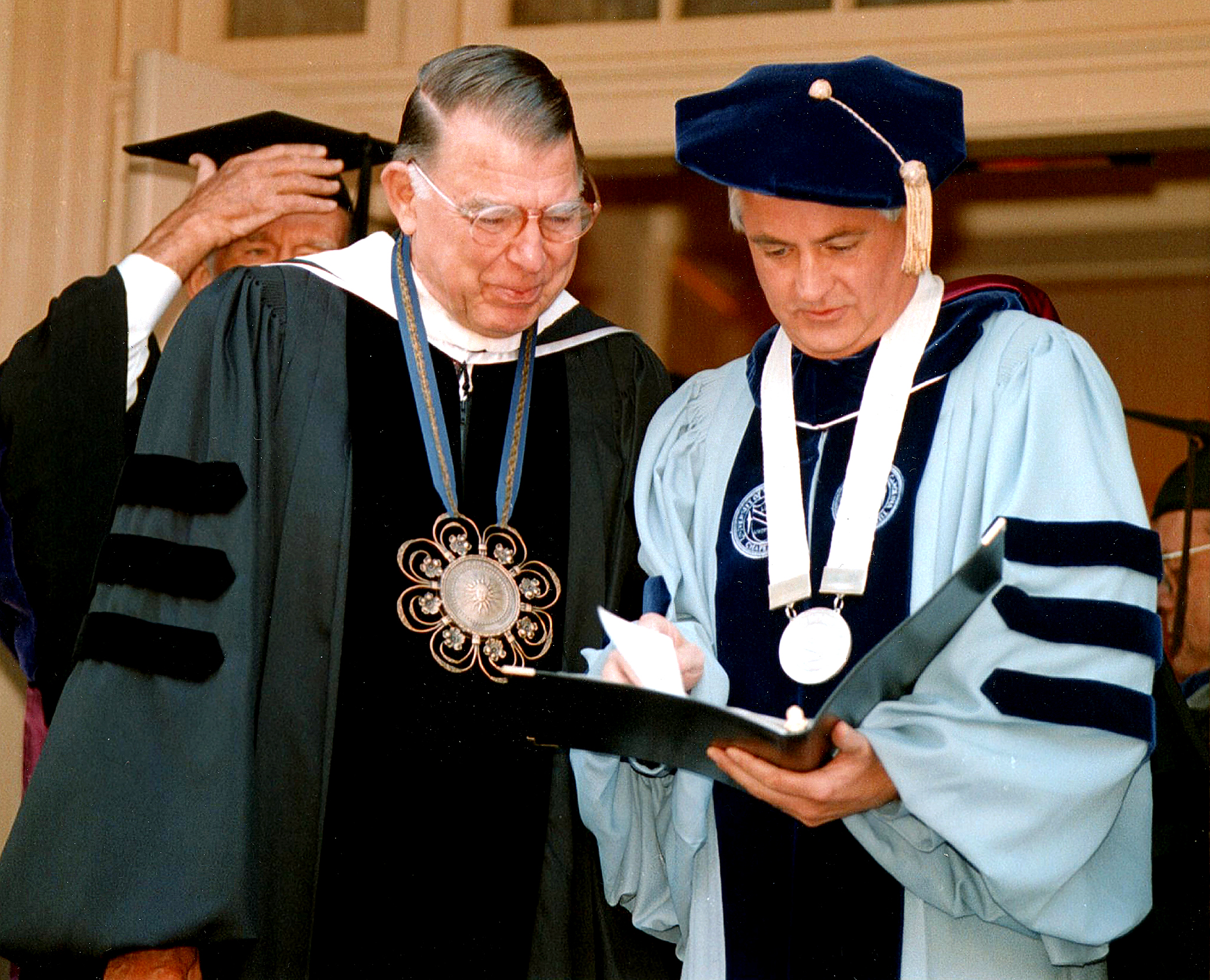

C.D. Spangler Jr. ’54 named two of Carolina’s chancellors: Paul Hardin, shown here, and Michael Hooker ’69, seen in image below. (File photo)

Once the wealthiest man in North Carolina, C.D. Spangler Jr. ’54 was an intensely private business titan who held some of the most egalitarian and public-facing positions in society as a local and state leader in education. By the time he left the last of these roles — that of his 11 years as president of the UNC System — he had risen to the title of billionaire in the boardroom but tireless protector of working families beyond it, a complex man whose every move aimed to elevate the fortunes of the state he loved.

Spangler, who died Sunday at 86, was a study in contrast, a grounded native with a soaring resume. He was a corporate raider with a private plane who drove a practical Ford; a Harvard-educated businessman who remembered his fourth-grade public school teacher as one of his best instructors; a man who hosted a million-dollar fundraiser at his home for President George W. Bush but relished eating taco salad and chocolate milk with students at Lenoir Hall.

“I remember calling President Spangler when I was a first-year reporter for The Daily Tar Heel, figuring I’d leave a polite message and never hear back,” recalled Eric Johnson ’08, director of editorial strategy for the College Board. “A few rings later, there he was on the other end of the line, patiently explaining the politics of some obscure piece of University history. The University is in the business of education, and he never forgot it. I think that’s why he was so unfailingly generous with his time toward students.”

Spangler believed that no matter where a person may start in life, he or she could grow to unimagined heights with the support of a community that valued equality in education. Whether successfully lobbying for statewide public kindergarten in 1973, fighting to save Charlotte public school integration in the mid-1970s or strengthening schools as the chair of the State Board of Education in the 1980s, he viewed access and opportunity as the cornerstones of a prosperous society.

His official UNC portrait depicts him in front of a laptop, opened to a page that reads, “Article IX, Sec. 9” — the state constitutional mandate that higher education “as far as practicable, be extended to the people of the State free of expense.”

“I have no doubt in my mind,” Spangler scolded Carolina’s Board of Trustees in 1995, as they considered — and ultimately approved — a 42 percent tuition increase, “that if the tuition were $10,000, you would still be able to fill up the freshman class. But you would have a different type of student body than the one we now enjoy. A higher and higher tuition will result in an elitist university — an elitism of net worth, not brains.”

UNC System President Margaret Spellings called Spangler “a great North Carolinian, and he will forever be a giant of our state,” according to a report in The News & Observer.

“He will be remembered as a gifted business leader, a compassionate philanthropist and, above all, as a public servant who answered the call of the university at a critical time in its history,” Spellings said in a statement reported by WRAL. “He believed in the power of education to change lives and transform a state, and he made those possibilities into reality through his life’s work. The first in his family to go to college, Dick never forgot who our public universities were meant to serve. North Carolina is the prosperous, growing state that it is because of principled leaders like Dick.”

C.D. Spangler Jr. ’54

Spangler was 54 when he assumed the reins at UNC in 1985, following the 30-year tenure of William Friday ’48 (LLB), and like all successors to living legends, he was the subject of plenty of comparison and criticism. Friday had captained a system that had grown from three campuses to 16 and a budget that had risen from $14 million in 1956 to $1.4 billion in 1986. Once an ivy-covered enclave, higher education nationally had become democratized, dominated by public institutions like UNC that sought to prepare sons and daughters of farmers and mill workers for heightened possibilities.

But that made college a growing public business, too; and, set against this landscape, there seemed no more ideal a leader for UNC and its Article IX, Section 9 ethos than Spangler, a descendent of farmworkers who now occupied a rarified constellation of success.

After earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees in business from UNC and Harvard and completing a stint in the Army in 1958, Spangler returned to Charlotte and became president of his father’s construction company. Spangler Jr. grew it beyond even his ambitious father’s dreams and followed that feat by taking control of the troubled Bank of North Carolina in 1973. (His strategy to save the bank, which his father had founded, later became a case study taught by Harvard professors.) In 1982, he engineered its sale to NCNB, which later would become Bank of America. The deal solidified the Spanglers’ wealth and led to his entrance on Forbesmagazine’s list of 400 wealthiest Americans.

When UNC came calling, Spangler, who was then serving as chair of the State Board of Education at the behest of then-Gov. Jim Hunt ’64 (LLBJD), initially refused consideration. He believed the system needed an academic professional. It was his wife, Meredith Riggs Spangler, who told him: “You’ve made a big mistake. They’ve got thousands of PhDs. What they need is someone who can manage a complex university system.”

Spangler consented, and he used his business acumen to infuse UNC with outside funding that would bolster its reputation nationally and help buoy it through lean budgets. He pushed school leaders across all 16 campuses — not just the big research universities in Raleigh and Chapel Hill — to tie hiring and tenure to the procurement of research grants, which grew 185 percent over his tenure. He fought for a $310 million construction bond, creating more classrooms to support a student body made stronger by the higher admission standards he championed. And he is credited with installing inspired leadership in chancellorships systemwide; he wooed civil rights leader Julius Chambers ’62 (LLBJD) back to N.C. Central and pressured the UNC System Board of Governors to hire the system’s first two female chancellors.

Chambers returned to his undergraduate alma mater in part because of his respect for Spangler, who had built a coalition to ensure court-ordered desegregation’s success while serving on the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school board in the 1970s. Spangler’s children, Abigail Riggs Spangler and Anna Spangler Nelson, both attended Charlotte’s public schools at the time.

“They’ve got thousands of PhDs. What they need is someone who can manage a complex university system.”

–Meredith Riggs Spangler to her husband, C.D. Spangler Jr. ’54

But while his predecessor at UNC had charmed administrators and legislators, Spangler kept his own counsel and favored aggressive decision-making. The approach rankled some in the world of academia and governance.

BOG members Walter R. Davis and William Johnson used the 1989 athletics scandal at N.C. State — which led to the ousters of Athletics Director and Coach Jim Valvano and Chancellor Bruce Poulton — to call for Spangler’s resignation. They criticized Spangler’s management style and his lack of transparency about an investigative probe he ordered into the Wolfpack’s wrongdoing. Spangler, who instituted systemwide athletics reforms that included a ban on coaches also serving as athletics directors, was never in serious danger of losing his job; however, he acknowledged the distance BOG members felt from the process.

Spangler simply worked best in the solitary spaces of his intellect. Asked before his inauguration how he would know if he was succeeding, he told Business North Carolina, “I’ll depend on myself to realize that more than anyone else.”

Spangler with Chancellor Michael Hooker ’69. (File photo)

Although he had resigned the helm of his family’s companies when he took office at UNC, he continued to serve on corporate boards and to craft deals. In 1995, he made national headlines for his company’s $1.2 billion takeover of Charlotte-based wallboard maker National Gypsum, of which he had been board chair — a move that would help make him a billionaire. The maneuver drew criticism from observers who felt he had divided interests. But Spangler believed in multitasking long before productivity was a buzzword: “Having a single problem is overwhelming,” he said. “Having 10 problems is easier to handle.”

Despite the spotlight his life attracted, Spangler preferred hiking, camping and tinkering with grandfather clocks to holding court with those who might polish his ego.

“I just don’t think I can personally persuade you of anything you don’t already believe,” he told The News & Observer in 1996. “I believe people do what’s right because it’s right, not because of any slick presentation.”

“I worry about Dick Spangler and history,” longtime friend and former UNC System Vice President Wyndham Robertson said then. “His habit of not explaining himself and not laying things out will make it hard to evaluate him.”

But Spangler’s family story revealed his mind, by way of his heart. Beneath his eye-popping wealth lay the memory of a grandfather who could not read and the college education that eluded his farm-raised parents. Although those fates would not be his, their echoes, and any lost opportunities that resulted from them, rang through Spangler’s principles and his ambition and informed his public service.

C.D. Spangler Jr. ’54 talks with fellow former UNC presidents William Friday, Molly Corbett Broad, Erskine Bowles and Tom Ross about the legislation that brought all 16 of North Carolina’s public universities into the UNC System.

“Dick Spangler fought against tuition increases, understanding that many North Carolinians can’t afford what others consider the modest cost of attending a state university,” Robertson said in a statement carried by WRAL on Monday. Robertson, who was the first woman to become a UNC System vice president, noted: “He made the system a more comfortable place for women and minorities. He sought them out and pushed them into positions of leadership. He was a great boss. … I had some tricky moments, but I always knew he had my back. He loved North Carolina and often said being president was the best job in the world.”

Born April 5, 1932, in Charlotte, Clemmie Dixon Spangler Jr.’s mindset sprang from the self-made drive of his father, C.D. Spangler Sr., who left his family’s Cleveland County farm for the Queen City in the 1920s to make a life with his mind as well as his hands.

There, the father used his position as a secretary to a developer to persuade his boss to give him a plot of land to build on speculation. He sold that house when the economy began its rebound from the Depression’s depths, then built another, and another, and C.D. Spangler Construction was born.

Spangler Jr. marveled in his father’s work, in which men willed the ground beneath them to yield new forms of promise. And he learned deal-making, a skill he put to use early. As a high-schooler Spangler Jr. paid a UNC cheerleader $10 to hand him a Charlie Justice ’50 jersey left on the sidelines after a game — enough, the undergraduate told Spangler, to buy whiskey for a party. As Spangler left the stadium, though, alumni offered him $100 for the jersey. He kept it, donating it to the University decades later.

“For someone like me, whose whole life experience is tied to North Carolina,” said Spangler, “the UNC job was a significant opportunity.”

When he first arrived at Harvard, with its vast history of privilege, Spangler wondered if he “might be in the wrong place.” The feeling passed quickly but the effect did not. Throughout his career, Spangler felt a responsibility to safeguard the fortunes of North Carolina’s citizens and its economy against inferiority, to see them flourish as abundantly as any other. In business, he took risks to prevent companies from leaving the state, as with his attempt to buy out RJR Nabisco in 1988. (A year later, the company moved from “bucolic” Winston-Salem to “nouveau-riche” Atlanta at the insistence of its chief executive.) In the public schools, Spangler preached better preparation. And at UNC, he saw 16 campuses to both protect and to push forward, the ultimate marketplace of Tar Heel State possibilities.

“For someone like me, whose whole life experience is tied to North Carolina,” said Spangler, who donated his salary back to the system schools, “the UNC job was a significant opportunity.”

His children continue his public service legacy: Anna currently serves on the Board of Governors, while Abigail founded Protest Easy Guns, a national movement to reduce gun violence.

“Dick’s fervor for affordable education for all North Carolinians and his fight for the common man have made him such an uncommon man,” childhood friend Ned Hardison ’55 said when Spangler was awarded the GAA’s Distinguished Service Medal in 2006. Spangler also received the Alumni Achievement Award from the Harvard Business School in 1988, where his name adorns the student life center; and the William Richardson Davie Award from the UNC Board of Trustees, the highest honor given by the board. From 2003 to 2004, he served as president of the Harvard Board of Overseers. The UNC System’s General Administration buildings were renamed the Spangler Center in 2008, to honor C.D. and Meredith Spangler.

The C.D. Spangler Foundation has helped fund more than 120 endowed professorships across UNC System campuses — one or more on every system campus — and funded numerous teaching and student scholarships in Charlotte public schools in the years since Spangler’s retirement from the system.

When C.D. Spangler Sr. died in 1987, Spangler Jr. told The Charlotte Observer that his father always chastised him for not setting his sights high enough — even after he had made his fortune. After UNC named his son its president, the elder Spangler conceded, “That might well be high enough.”

“Being president is good for many reasons,” Spangler Jr. said when he announced his retirement in 1996. “One is that when you work on behalf of education for students, you feel you are on the side of angels. More than I could ever adequately express, I thank you for letting me be president of the University of North Carolina.”

— Beth McNichol ’95