From No. 1 to Persona Non Grata : A Peace Corps Story

Posted on Sept. 24, 2021

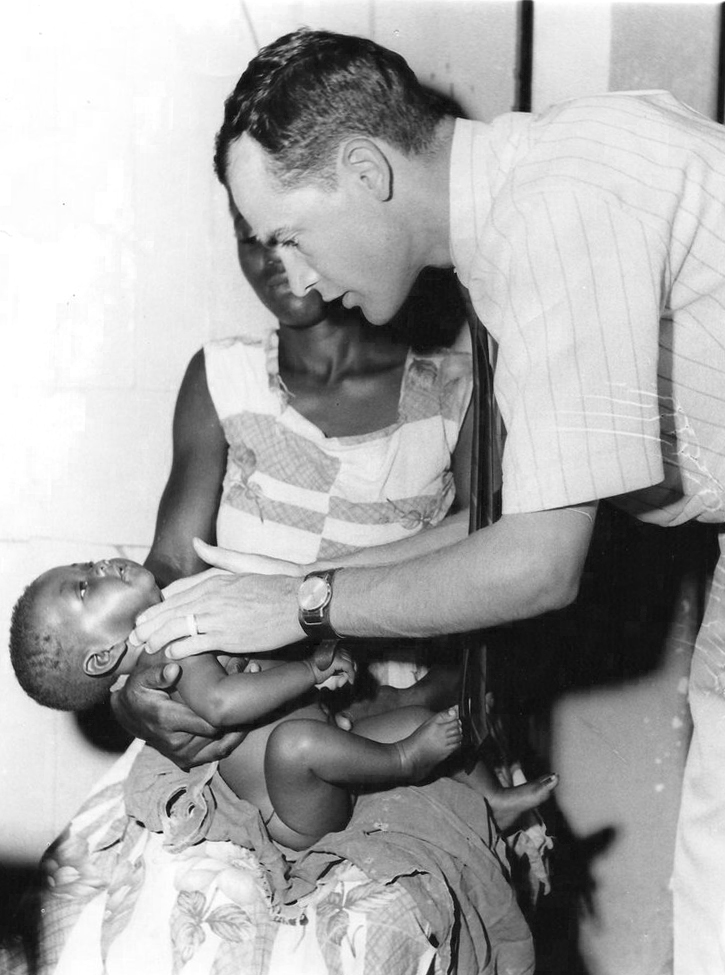

As a Peace Corps volunteer in Malawi from 1967 to 1969, Jack Allison ’66 worked in a clinic for babies alongside a Malawian physician assistant in an area where children often were malnourished. (Photo courtesy of Jack Allison ’66)

Two days after graduation, Jack Allison ’66 and his fellow UNC Men’s Glee Club members flew to New York to appear on The Ed Sullivan Show, opening for the Dave Clark Five, the superstar British Invasion rock band. For Allison, who made a name for himself on campus as lead singer for The One-Eyed Jacks, the Sullivan appearance and the glee club’s European tour immediately thereafter were a dreamy signoff from Carolina.

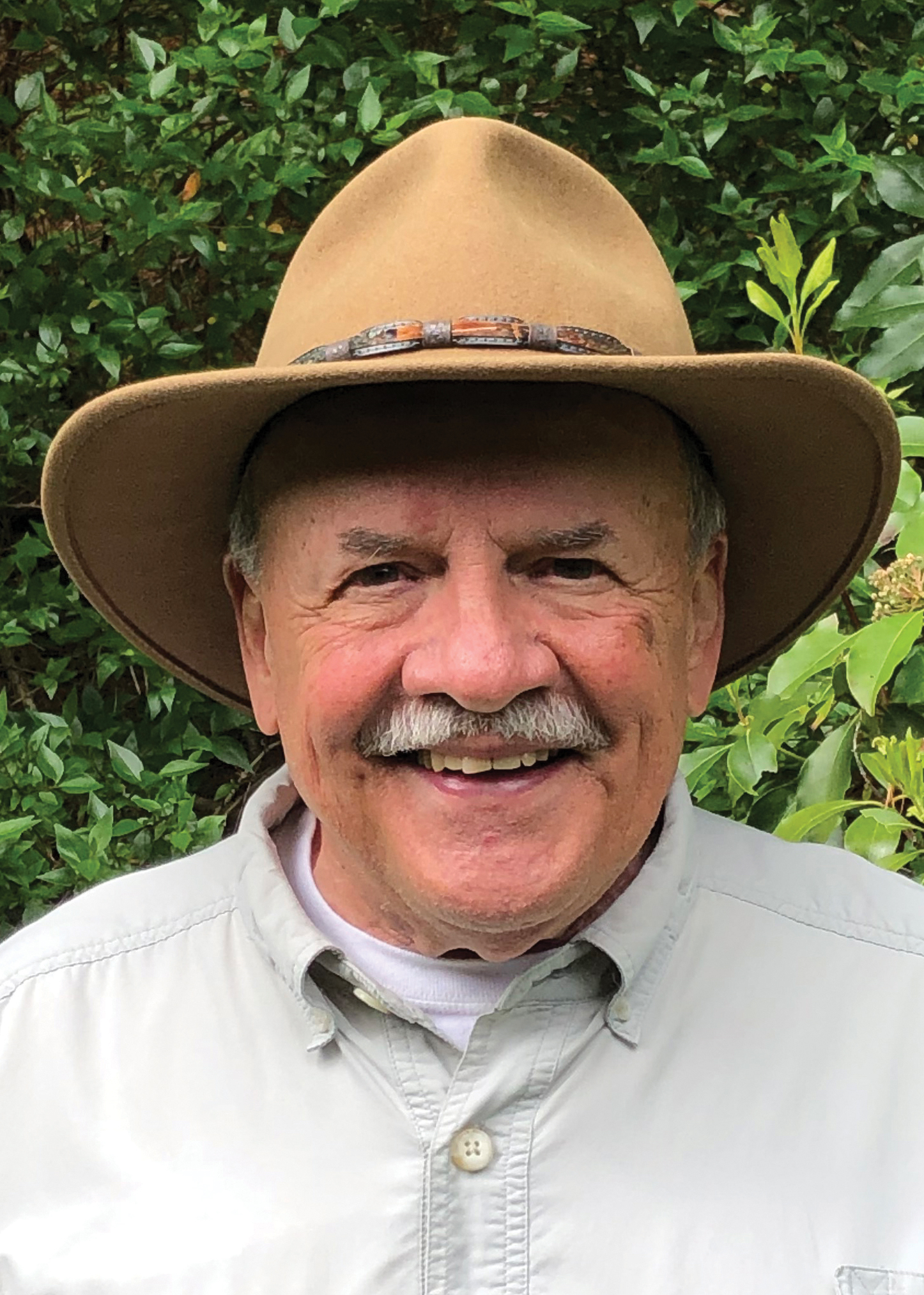

Jack Allison ’66

Just a year later, Allison recorded a song that went straight to No. 1 — in Africa.

He reached the top of the charts after joining the Peace Corps, hoping the two-year stint would help him decide between a career in ministry or medicine. He was sent to Malawi, a narrow, landlocked nation in south-central Africa and one of the world’s poorest countries. Allison was no stranger to hardship and poverty: His parents had married young — his father was 23 and his mother 15 — and he was born two years later. His parents later split up, and he grew up in a mobile home, prompting other kids to call him “trailer trash” as he moved up and down the East Coast, attending 17 schools by seventh grade.

As a Peace Corps volunteer from 1967 to 1969, Allison was posted to a remote village, where he lived in a mud hut; had close encounters with baboons and deadly snakes; learned the main language, Chichewa; and worked in a clinic for babies alongside a Malawian physician assistant, focused on nutrition education in an area where malnourished children were commonplace.

The hands-on work foreshadowed his return to UNC, where Allison earned his master’s in public health in 1971 and graduated from medical school in 1975. He went on to a 40-year career in academic emergency medicine, including serving as chief of staff at two Veterans Administration hospitals. But before he was “Dr. Allison,” the young American exploited his musical talents in ways Malawi had never seen.

“Are You the One?”

First, Allison wrote a song aimed at mothers, Brush the Flies Outta Your Babies’ Eyes, aspiring to help prevent the spread of pink eye. He recorded it in Chichewa with a popular Malawian band, and it was played incessantly on the country’s lone radio station.

• Listen to some of Dr. Jack Allison’s jingles

• Read about the Peace Corps experience of Andy Trincia ’88, a freelance writer and editor who lives in Romania, where he served 2002-04, “Grabbing Small Victories,” and Carolina’s contribution to the ranks of the Peace Corps, “High Idealists,” in the July/August 2003 Review

While it was a bona fide hit, Allison’s next jingle soared to (and stayed at) the top of the charts in Malawi for three years — Ufa Wa Mtedza (The Peanut Flour Song), which urged mothers to add peanut flour to cornmeal porridge, a daily staple, giving children a vital protein source. The song’s catchy surf-guitar beat and simple lyrics resonated with Malawians and catapulted Allison to national stardom.

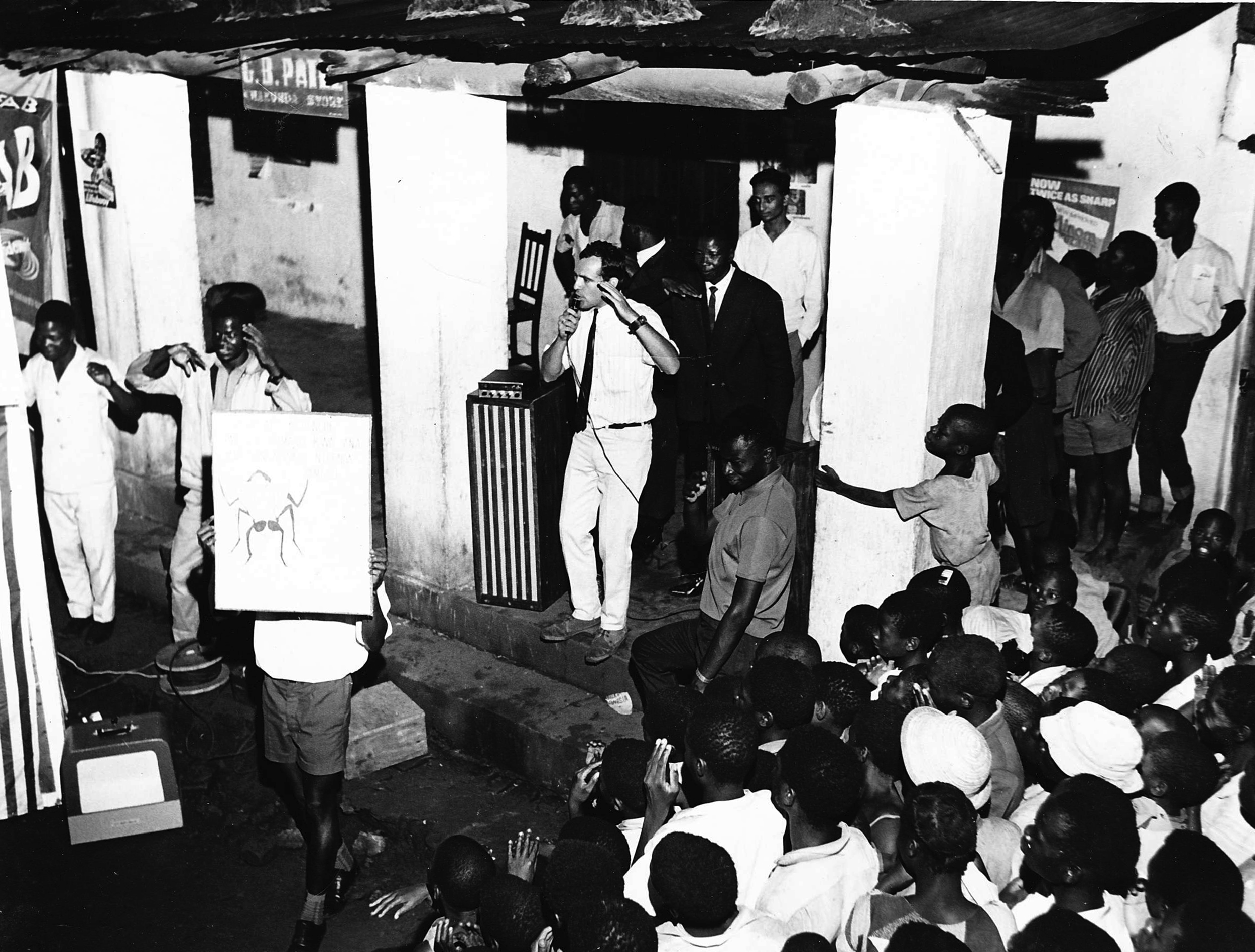

Not only was Allison’s music effective in promoting awareness of a life-threatening issue, but it raised needed funds for development projects; royalty checks flooded in, but under Peace Corps rules, he was not allowed to profit personally. An overnight sensation, he was interviewed by national media and could go nowhere in Malawi without being recognized, especially after he did tours and puppet shows, teaming up with corporate sponsors, including Colgate-Palmolive and Coca-Cola, to help the cause.

Peace Corps brass were thrilled. The U.S. ambassador paid a visit to Allison’s far-flung village, and Allison was featured in European documentaries. He plowed ahead with his health education mission, all while seeing patients daily in the clinic, writing jingle after jingle in Chichewa on pertinent topics — including rabies, hand-washing after using the latrine, boiling drinking water, tuberculosis prevention and blood donation, among others — and quickly becoming a household name in Malawi.

Allison used music and wrote jingles played on the radio to promote nutrition and hygiene. (Photo courtesy of Jack Allison ’66)

“Everywhere I went, especially in the bigger cities like Blantyre, the commercial capital, people would see me and say, ‘Are you the one?’ ” Allison recalled, with a tinge of bemusement even today. “It was always, ‘Are you the one?’ ”

The retired physician, now living in Asheville, recounts the improbable story in his memoir, The Warm Heart of Africa: An Outrageous Adventure of Love, Music, and Mishaps in Malawi, published by Peace Corps Writers in 2020. The title comes from Malawi’s nickname based on its mild climate and kind, hospitable people.

Banished by Banda

But Allison’s newfound celebrity in Malawi eventually caused friction at the highest level. Newsweek labeled Allison more popular than Malawian President Hastings Banda, leading that autocratic leader to declare Allison persona non grata in a nationally broadcast speech and order him deported. Allison was well into his third year of service after receiving special permission from the Peace Corps to extend one year but was forced to depart early. He was heartbroken. Banda also tried to end the Peace Corps in Malawi, but cooler heads prevailed — it was too valuable, as the American volunteers made up 60 percent of the country’s secondary school teachers.

Despite the bitter ending, Allison knew two things: He wanted to pursue a career in medicine, and Malawi had a special place in his heart. “Being a Peace Corps volunteer solidified my desire to live a life of service, because those three years were truly transformative,” Allison said.

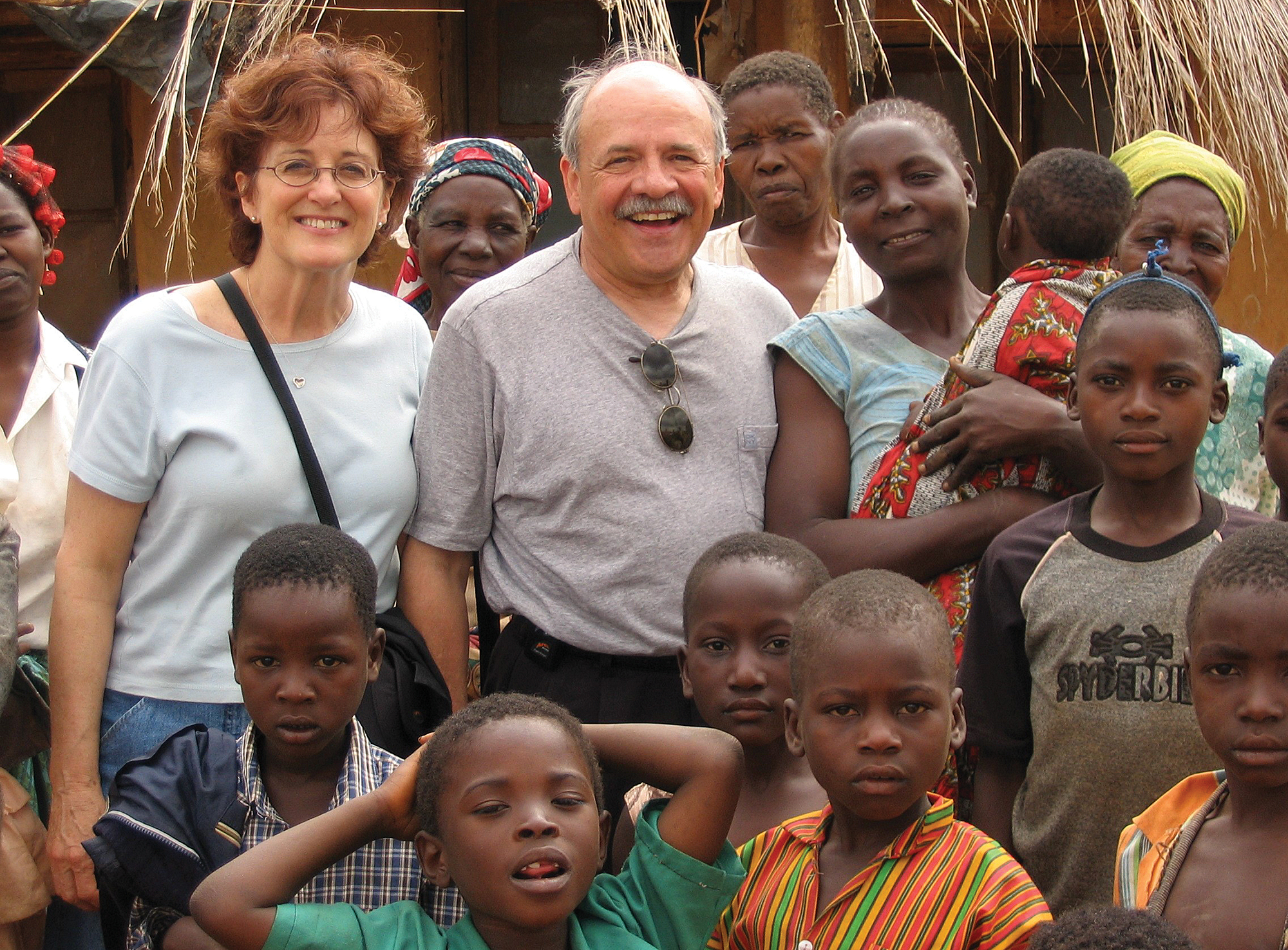

Allison and his wife, Sue Wilson, have visited Malawi several times; he has provided free medical care there and in other countries. (Photo courtesy of Jack Allison ’66)

He went back to Malawi in 1994 for the first time since his Peace Corps days. Upon arrival at the airport in Lilongwe, he gave an impromptu press conference partly in Chichewa. He and his wife of 40-plus years, Sue Wilson, have visited Malawi several times. They have one son and — “through the miracle of adoption,” as he puts it — three adopted daughters, seven grandchildren and four great-grandchildren. He jokes that it took him another 25 years to write his book, from which he’s donating all proceeds to nonprofits, including anti-hunger and medical organizations

Allison never stopped the music. He has written some 125 songs and jingles and recorded more than 110 of those, including tunes on AIDS prevention and, most recently, a song to promote safety precautions to combat COVID-19, which prompted Malawi’s ambassador to the United States to write Allison a letter of commendation for all he’s done for the African country.

Last year’s worldwide evacuation of Peace Corps volunteers due to COVID-19 left Allison “sorely disappointed,” but he considered it the right call. He sits on a 24-member special advisory council of the National Peace Corps Association, representing the 240,000 Americans who have served. The group is tasked with reshaping the Peace Corps, including increasing diversity, improving the health of volunteers and ensuring future viability of the agency.

Allison continues to give back to Malawi and has aided other countries, providing free medical care in Haiti in 2010 and in Kenya, Somalia and Zambia in 2012. Through Allison’s music, he and his wife have raised more than $165,000 for nonprofit organizations, including AIDS orphan charities in Malawi.

— Andy Trincia ’88

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.