Lightening the Blues

Tim Duffy ’91 developed a vision for preserving traditional music that included the legendary musicians themselves.

by David Menconi

Luther “Captain Luke” Mayer was on the phone from Winston-Salem. The longtime blues-singing fixture in his hometown was laid up in hospice care — at rest in the days before his death on May 12 at age 87 — but you’d never have known it from his demeanor on the phone.

“Oh, they’ve got me all fancy up in here now,” Mayer said in his basso profondo drawl (think Barry White, only more relaxed and much, much deeeeeeper). “I can hardly see the walls for all these lights and things shinin’ on me. I’m gonna be baked up real soon, just like a chicken. I ain’t lyin’, I’m gonna be a big star one of these days!”

“Luke, you are a star,” Tim Duffy ’91 (MA) spoke up in the background, and they both laughed.

“Oh, I am a big star, am I? I did not know that,” Mayer said between cackles, before turning serious and getting back to the phone call. “But I’ve known Tim a long, long time. Just about raised him and his old lady, and their little bambinos, too. They’re the same as mine.”

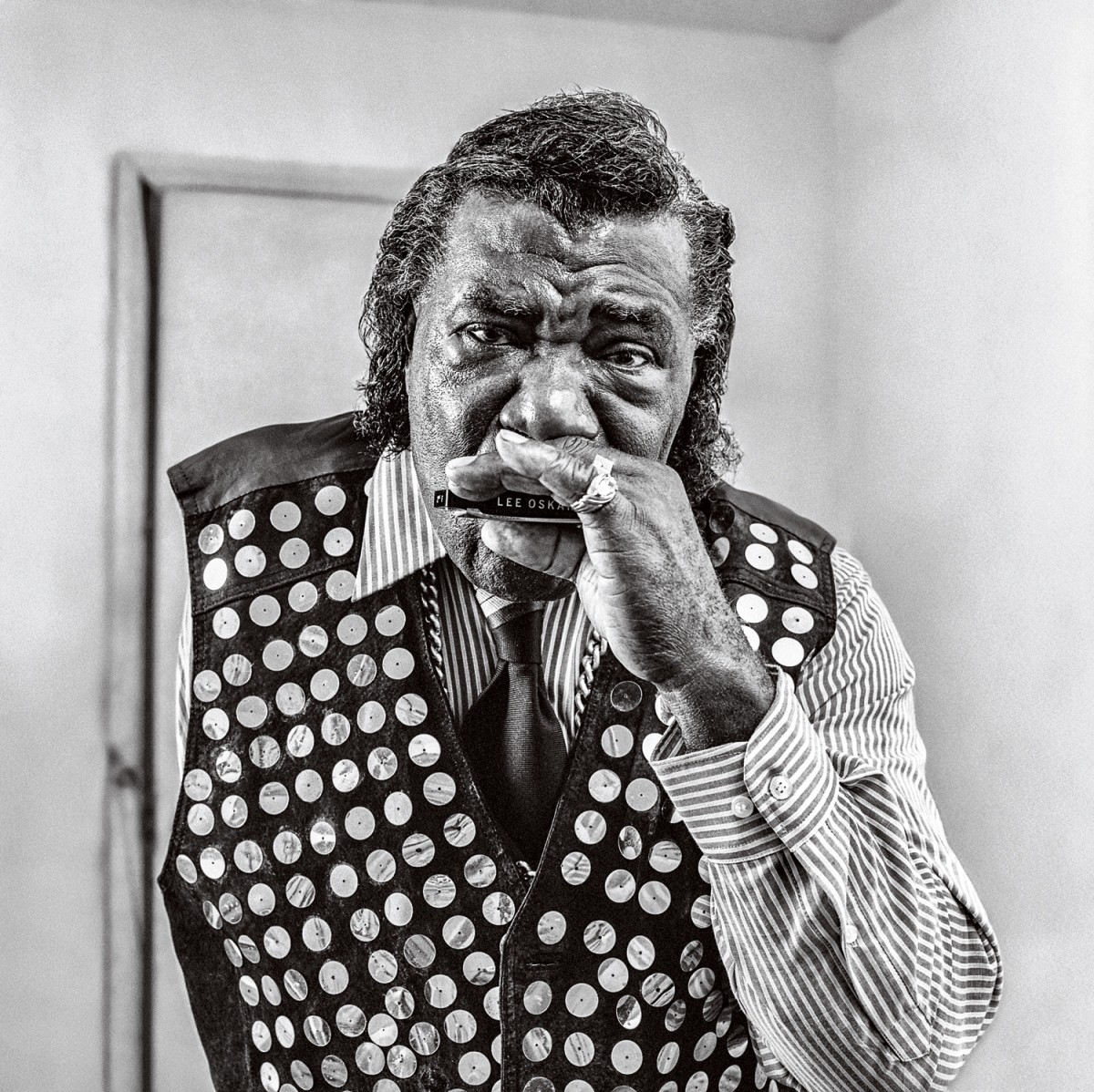

Luther “Captain Luke” Mayer was a well-known and well-traveled bluesman and a godfather-like figure in Winston-Salem. (Photo by Tim Duffy ’91)

Luther “Captain Luke” Mayer (Photo by Tim Duffy ’91)

Mayer and Duffy met in the late 1980s, when Duffy was still a folklore graduate student at UNC and learning his way around the Piedmont blues. And in 1994, when Duffy and his wife, Denise, set out to help blues people through the Music Maker Relief Foundation, one of the first artists they signed up was Captain Luke — a great character and a godfather-like figure in Winston-Salem, where he would hold court behind the wheel of a large automobile in his ever-present captain’s hat, puffing cigars.

In performance, Mayer could bowl listeners over, making every stage feel like a late-night salon. But he was not in the best of health the last two decades of his life, and Duffy was there with help that counted. In addition to a regular stipend to pay for prescription medicines, Music Maker regularly chipped in grants for emergencies large and small, from hospital stays to car repairs.

Now that was coming to an end. And while Mayer was hardly Duffy’s first end-of-life vigil from among the Music Maker musicians, he was one of the most memorable. A few weeks before his death, Mayer was too ill to make it to the Shakori Hills Festival in Chatham County, where he had been a regular. Dom Flemons from the Carolina Chocolate Drops dialed Captain Luke up from the stage and led the crowd in chanting, “We love you.”

“I’ve never seen a guy die the way Luke has,” Duffy said shortly before the end. “He really is like my family. Music Maker has a board of directors and all, but the musicians we work with like Luke, they’re kind of the real board. The first wave of them that I started working with are almost all gone now. But it’s endless. There are always more artists out there, and so many of them need help.”

Dom Flemons of the Carolina Chocolate Drops, UNC folklorist Bill Ferris and Duffy at Love House on the Carolina campus. The genesis of Music Maker was in Ferris’ classes, where Duffy encountered musicians and witnessed an entrepreneurial evolution in studying folklore. (Photo by Tim Duffy ’91)

Key connections

It was probably inevitable that Duffy would wind up spending his life and career doing work like this. He showed all the signs of being a roots-music archivist and reclamation artist from a young age. Growing up in his native Connecticut, the teenaged Duffy used to sneak onto campus at Yale University to crash Bill Ferris’ classes when he’d bring in guests to perform, like Memphis legend B.B. King and Delta bluesman James “Son” Thomas.

“Tim told me later that seeing people like that in my class was a turning point for him, really formative,” said Ferris, the eminent folklorist who is now senior associate director of UNC’s Center for the Study of the American South.

Before coming to UNC to do graduate work in the folklore program, Duffy studied ethnomusicology at Warren Wilson College in Asheville and Friends World College, studying everything from linguistics to oud music during a stretch of fieldwork in Kenya. One of his professors at Friends was Robert Leonard, who is more widely known as a founding member of Sha Na Na, the 1950s-style oldies band that was on the bill at Woodstock. But since then, Leonard has become renowned as a linguist, and he taught Duffy linguistics field-research techniques he would use in Kenya.

“When I was in college during the 1980s, folklore was really changing,” Duffy said. “The emphasis was evolving from an anthropological viewpoint to more of an entrepreneurial one — not thinking of the people you studied as subjects so much as partners in your research. You don’t talk about them so much as work with them and try to help them out. I probably took that to heart more than most people.”

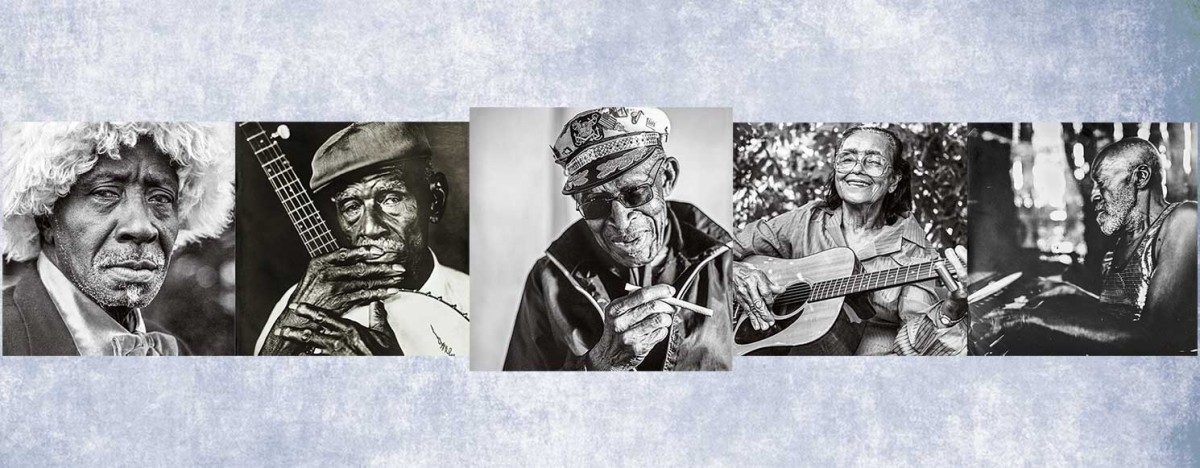

Guitarist Etta Baker (Photo by Tim Duffy ’91)

One-armed harmonica master Neal Pattman (Photo by Tim Duffy ’91)

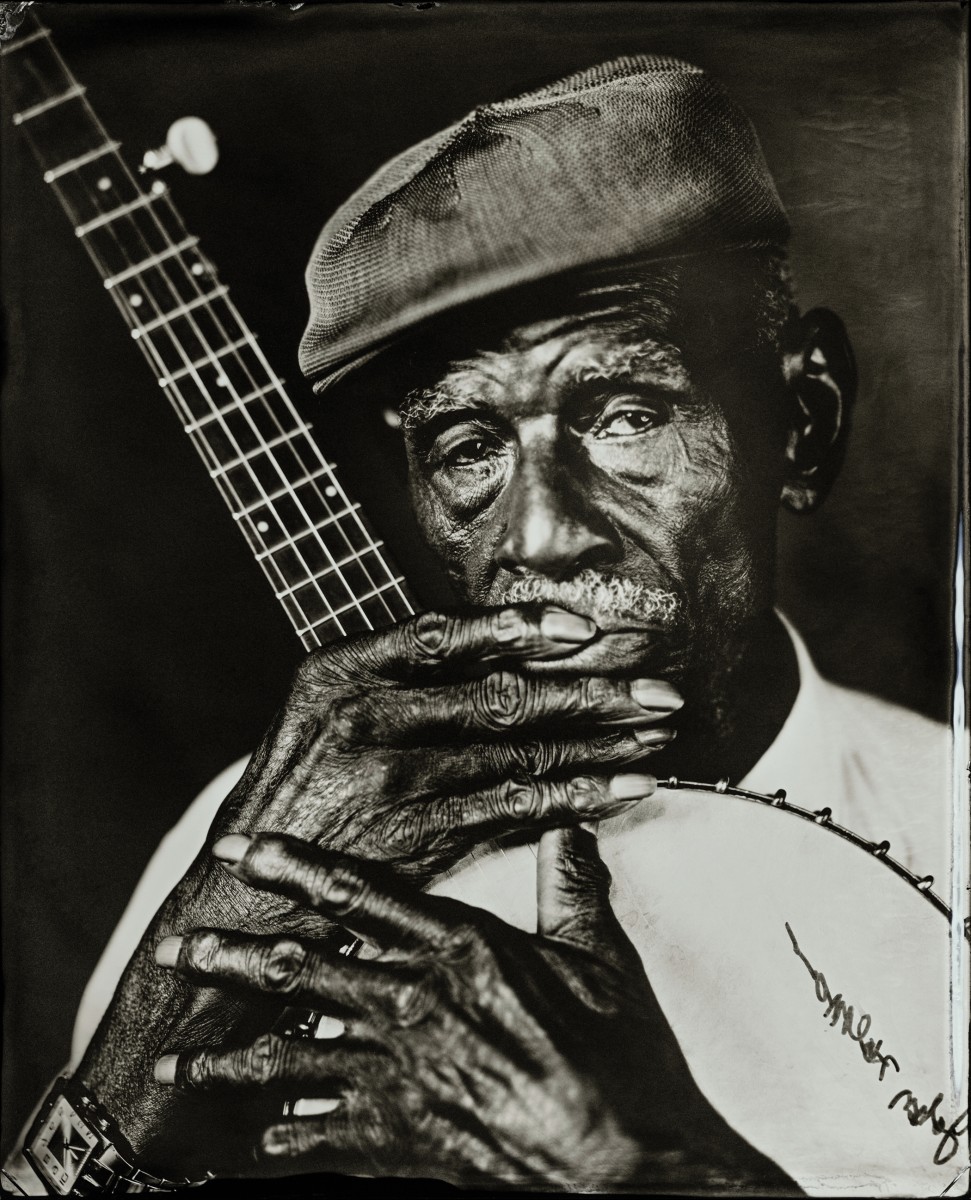

Bluesman John Dee Holman (Tintype Photo by Tim Duffy ’91)

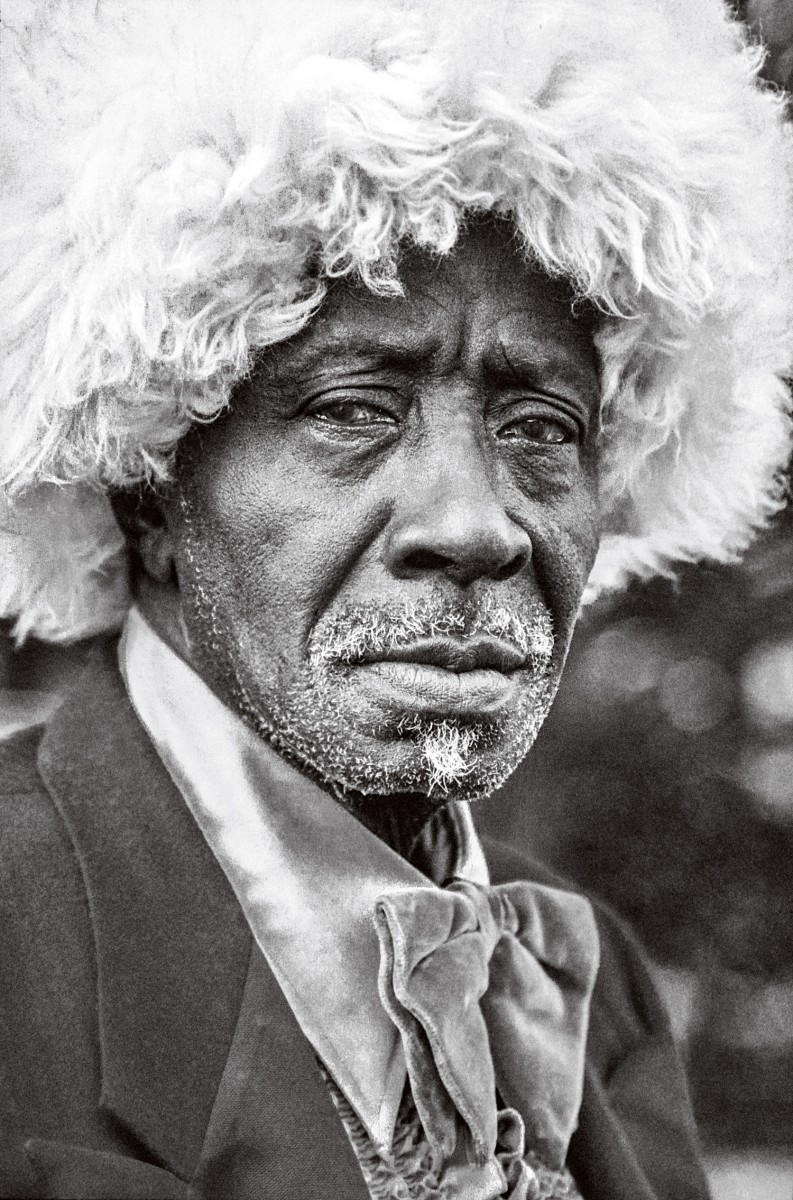

“Guitar Gabriel” (Photo by Tim Duffy ’91)

James “Guitar Slim” Stephens (Photo by Tim Duffy ’91)

A seminal scholarly moment for Duffy was when he took “Vernacular Traditions of African-Americans” from anthropology associate professor Glenn Hinson in the fall of 1989. Duffy wanted to get out in the field and connect with classical-style acoustic blues musicians to take down some oral history. But the Chapel Hill and Durham vicinities had been pretty well-researched by then.

Greensboro, however, was still more or less wide open. So Hinson gave Duffy the assignment of going over to document James “Guitar Slim” Stephens, and they hit it off. Stephens would die not long after they connected. Stephens also told Duffy he should track down Guitar Gabriel (aka Nyles Jones), an underground legend of the old medicine-show circuit who had been knocking around Winston-Salem for years.

After he finished his master’s at UNC in 1991, Duffy was working as a substitute teacher at a middle school in Winston and wondering what to do next. He kept hearing stories about Guitar Gabriel, and a fortuitous tip from one of his students led Duffy to a bar on the not-so-good side of town. There he met Gabriel’s nephew and finally Gabriel himself.

“That was the big connection,” Hinson said. “Gabriel opened up this whole world of Winston-Salem artists, and he introduced Tim around to everybody. That community would become the core of Tim’s artistic clientele a few years later.”

Duffy became Gabriel’s sideman and confidante, playing alongside him up until his death in 1996. By necessity, the gig often involved serving as caretaker for the older man, and Duffy would help out when and where he could. Gabriel wasn’t the only one struggling to get by. He introduced Duffy to his blues-playing peers across the Carolinas — musicians including Durham blues fixture John Dee Holeman, one-armed harmonica master Neal Pattman and master guitarist Etta Baker — all of them older, largely unheralded and confronting choices like whether to buy food or prescriptions.

Duffy with one of the early Music Maker groups. Front row, from left, are Cootie Stark, Captain Luke, Cueselle “Mr. Q” Settle, Willa Mae Buckner. Back row: Deborah and Neal Pattman, Haskel “Whistlin Britches” Thompson, Macavine Hayes, Alvin “Little Pink” Anderson. More recently, Music Maker shepherded the connection between the Carolina Chocolate Drops and fiddler Joe Thompson that led the group to a Grammy. (Photo by Tim Duffy ’91)

Triage, rehab and income

But even though they were mostly forgotten and trying to survive on meager disability payments, most of them were still playing music and playing it well. Duffy was struck by their artistry as well as the desperation of their impoverished circumstances. So an idea started taking hold, based on an undergraduate class he’d taken years earlier called “The Politics of Culture.”

“Between school and my experiences in Kenya and then North Carolina, I’d spent most of my young adult life hanging out with these great folk musicians who were living in dire poverty,” Duffy said. “I can’t compare myself to Ry Cooder — he’s a front man, while I was a side guy for Gabriel — but I was kind of taking the same route as him and other young white guys, going deep into a culture and coming out with a unique thing. What I wanted to do was help all these people out. So I made a new model.”

That new model was Music Maker Relief Foundation. Duffy admits he’s an unlikely figurehead for such an organization, describing himself as “a Yankee from Connecticut with ‘carpetbagger’ written all over me,” so he went out of his way to get the musicians as involved as possible from the start. Guitar Gabriel was one of Music Maker’s first board members, and worldly bluesman Taj Mahal emerged as an early and enthusiastic supporter and spokesman.

Music Maker’s main missions are twofold, split between short-term triage and long-term rehabilitation. It provides direct support to musicians who are in crisis, medical or otherwise, while also trying to derive commercial success, albeit lately, from their considerable accomplishments.

Music Maker was initially based in Pinnacle, near Gabriel’s Winston-Salem home turf. R.J. Reynolds emerged as an early benefactor, thanks in part to lobbying from one of its advertising representatives, Bill Puckett, who eventually would join the Music Maker board of directors.

“I went to Reynolds in the late ’90s after Rolling Stone did a blues edition with some of the Music Maker guys,” Puckett said. “And I told them, ‘This is big, let’s do a tour.’ It was 36 cities, they hired Taj Mahal as lead act with the Music Maker acts, and they spent $15 million promoting the tour, running ads, paying everybody. That was the Winston Blues Revival Tour. I wouldn’t say it launched Music Maker because they really launched themselves. But it helped put them on the map.”

Eventually, the Duffys relocated the Music Maker operation to Hillsborough, where they operate the organization out of a house festooned with funky works of outsider art. A studio for recording and photography is nearby.

So is a cemetery, just across the street. “We’re just trying to keep everybody out of there for as long as we can,” Duffy said.

Denise and Tim Duffy in the basement of Music Maker’s headquarters in Hillsborough, where they moved the company from the N.C. foothills. (Photo by Anna Routh Barzin ’07)

Finding new audiences

Music Maker has a core of major donors who contribute large sums and some influential help — its advisory board includes Bonnie Raitt, Jackson Browne, Dickie Betts, Tift Merritt ’00 and Pete Townshend. But its backbone is still made up of smaller contributors who send in anywhere from $20 to $100 annually. Last year’s 20-year anniversary produced a lot of attention and an uptick in donations. By the time the current fiscal year ends, Music Maker will have paid out some $100,000 in direct aid grants and set up concerts that earned its musicians another $110,000.

“We’re putting more than $200,000 out there,” Denise Duffy said. “And that doesn’t even include a lot of the live work our acts set up themselves. We’re unusual for most nonprofits in that we’re not really grant-funded. We do some, but most of our money comes in from private donations and program revenue. We’re not just presenters, and we’re not just an aid agency, which makes us kind of unconventional.”

Music Maker has had to take some unusual byroads in recent years to generate revenue for its musicians. A fair amount of its live performances over the past year haven’t taken place at festivals or nightclubs but in art museums, accompanying a 20-year-anniversary visual-art exhibit called “We Are the Music Makers” that has played throughout the country.

“Audiences are in unconventional places these days,” Denise Duffy said. “So wherever they are, we’ll go find ’em.”

One reason for that is that the bottom has dropped out of the recorded-music market. In its early years, Music Maker used to sell a lot of compact discs for its artists, about $60,000 worth a year. Now sales are a fraction of that.

“We might sell $12,000 worth of them a year now,” Duffy said. “But we still have to make them because you can’t book shows unless you put out new releases. So we still do about 12 CDs a year.”

Samuel “Ironing Board Sam” Moore is the star of the company’s 2014 release — and of a spray starch commercial. (Photo by Tim Duffy ’91)

Music Maker’s current releases include 2014’s “Ironing Board Sam and the Sticks,” by South Carolina native Samuel “Ironing Board Sam” Moore — so named because he uses an ironing board as a stand for his keyboard. But Ironing Board Sam is making a lot less money off album sales than from a particularly inspired commercial endorsement that Music Maker helped arrange: pitchman for Faultless Spray Starch.

“There’s always been a sort of creative effervescence around Music Maker,” Hinson said. “Early on, they had some ideas that seemed a little too far-reaching. But they ran with them and made them work. For all the naysayers there were early on, Tim’s vision is very much a good one. Music Maker has gotten a lot of people more of a hearing in their later years and also made their lives materially much better.”

That certainly goes for Ironing Board Sam, who used to play on the old R&B television show Night Train when he was young. But he was in a state of near-homelessness when he entered the Music Maker fold five years ago. Now, at 76, he has a thriving career that includes tours of Europe and a choice performance slot at this year’s New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. And he could not be more pleased about endorsing a starch brand.

“You should see the commercial I did for them, it’s outtasight,” Moore said. “Tim’s been wonderful to me. Not that I’d ever really retire, but I was in that state of mind. Music Maker’s good for all blues musicians who’ve had a hard time. They help get people back on their feet to make some money. When blues musicians go down, it’s not because they’re lazy but because styles change. The blues trend, I’m still on it. It’s all I know how to do.”

The next generation

Part of Music Maker’s preservation mission involves the music as well as the musicians, keeping old styles of blues going. Music Maker started a program called “Next Generation Artists” in 2005, and its first act was a newly formed old-time trio of young African-Americans in need of musical guidance. They were the Carolina Chocolate Drops, and Duffy helped connect them with Joe Thompson, an old-time fiddler from nearby Mebane.

The Chocolate Drops accompanied Thompson on the 2008 album “Live! With Joe Thompson,” and they also released 2007’s “Dona Got a Ramblin’ Mind” on the Music Maker label (still the organization’s top-seller at 25,000 copies) before departing for the major label Nonesuch. They went on to crack the pop charts, an almost unheard-of feat for traditional music, also winning a Grammy Award for best traditional folk album in 2011.

Singer/fiddler Rhiannon Giddens has emerged as a star in her own right, releasing a high-profile solo album produced by T-Bone Burnett (the tastemaking auteur behind O Brother, Where Art Thou? and other Americana blockbusters). Still, Giddens said earlier this year that she’d trade it all “for one more hour with Joe Thompson,” who died in 2012 at age 93.

“Joe Thompson’s end of life was very, very comfortable, thanks to the Chocolate Drops,” Duffy said. “They helped make him a lot of money because that album sold for years. And what we were able to do for the Chocolate Drops was to help give them a sense of authenticity, a base to start from, by introducing them to Joe.

“Even though the original old-timers are gone, there’s a new wave of guys in their 60s who have held onto the blues traditions.” A whole new generation of music makers for whom Music Maker could lighten up the blues.

David Menconi is a staff writer for The News & Observer of Raleigh.

Read more about some of the Music Makers and hear some some of their music.

about some of the Music Makers and hear some some of their music.

Tim Duffy is also preserving the Music Makers’ history with traditional tintype photographs.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.