Makeover on The Hill

The University needs more space to launch high-tech ventures, and Chapel Hill wants to revamp a long-struggling downtown. The proposed plans may radically transform the little village you’re used to.

by Eric Johnson ’08

Big changes are coming to downtown Chapel Hill, a makeover for Blue Heaven driven by the University’s need for more room to launch startup companies and the town’s desire to revamp Franklin Street.

After years of quiet discussion between Carolina’s leaders and town officials, a plan is underway to turn a district of takeout food and T-shirt shops into a hub for biotechnology startups, young professionals and free-spending visitors.

“I think we’ve reached a tipping point where this has to happen,” said Chancellor Kevin Guskiewicz. “For the University to grow the way it needs to, to become the anchor for economic development in this region, we need a strong and vibrant downtown.”

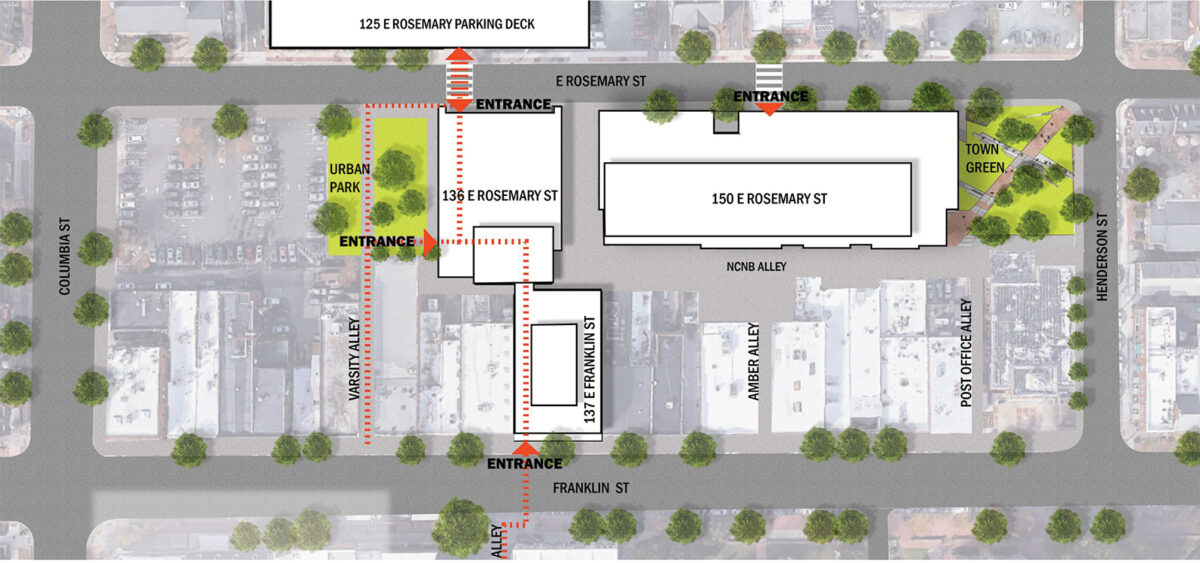

Grubb Properties says the redevelopment project will bring to downtown 1,000 jobs, 370,000 square feet of office and lab space, 700 more parking spaces, 150 apartments and two parks. Image courtesy of Grubb Properties

For the first time in decades, the University and the town have a shared vision for what that might look like. Last spring, Guskiewicz and Chapel Hill Mayor Pam Hemminger announced a joint development strategy, led by Innovate Carolina, UNC’s department for entrepreneurship and economic development and the Chapel Hill Downtown Partnership. Their plan envisions thousands of square feet of new offices and commercial lab space on East Rosemary Street rising just behind Sutton’s Drug Store, the Shrunken Head Boutique and the Franklin Street post office.

The plan also calls for moving UNC’s admissions office and its 50,000 annual visitors to a new office building on the south side of Franklin Street near the Carolina Coffee Shop along Porthole Alley. Downtown streets and sidewalks will get an overhaul sometime next year to accommodate more pedestrians, green space, outdoor dining and retail shops.

“You have a lot of smart people who are all pushing in the same direction,” said Matt Gladdek ’09 (MPA, ’12 MRP), executive director for the Chapel Hill Downtown Partnership. “We have a chancellor, a mayor, a town council and a town manager who all understand the importance of creating a beautiful downtown and an economic development strategy to go along with it. Right now, I think all the stars are aligned.”

For the first time in decades, the University and the town

have a shared vision for what a strong and vibrant downtown might look like.

A rendering of the proposed building at 150 E. Rosemary St., viewed from the northwest. Image courtesy of Grubb Properties

Falling behind

That alignment was helped along by the realization that Chapel Hill is behind the rest of the Triangle and other college towns nationwide in the race to nurture startup businesses and build an urban center that can attract business investment. Clay Grubb ’93 (JD), the CEO of Grubb Properties, which is leading one of the largest redevelopment projects, said Franklin Street long ago lost its status as the coolest and most vibrant spot in the Triangle, falling behind neighboring cities as they invested more in their downtowns. “The last 10 years have not been good to Franklin Street,” he said. “Everyone has flocked to Durham and Pittsboro and Raleigh.”

Grubb blames what he views as the town of Chapel Hill’s general opposition to development — “trying to stop all growth, put everything like it’s in a museum,” he said — but there’s also been a lack of coordination between the University and the town on how to redevelop the area.

The so-called “Ugly Deck” (top) at 125 E. Rosemary St. has been demolished. The town of Chapel Hill will replace it with a new parking garage with space for 1,100 vehicles (above). Grubb Properties owns the deck and traded with the town for the Wallace Parking Deck at 150 E. Rosemary. Grubb plans to replace the Wallace deck with a new structure (shown at top of page) containing office and wet-lab space. Images courtesy of Grubb Properties

Over the last three decades, while N.C. State University built Centennial Campus in South Raleigh to welcome public-private partnerships, and Duke invested hundreds of millions of dollars to transform downtown Durham into a technology and innovation hub, Carolina pursued a piecemeal strategy. UNC added startup labs in the Genome Sciences Building, tucked behind the School of Nursing; a small co-working office for entrepreneurs above a Franklin Street restaurant; and high-tech workshops where students can tinker with 3-D printers. But there was no master plan to link that activity to economic growth in Chapel Hill.

Carolina is one of the largest research institutions in the country, bringing in more than a billion dollars in grants each year from the federal government, state agencies, foundations and private businesses. Despite outranking Duke in federal research dollars — UNC is the sixth largest recipient and Duke ranks ninth — Chapel Hill doesn’t have the scale of medical and life-science startups clustered in downtown Durham. In 2021, Innovate Carolina counted more than 446 UNC-affiliated startups employing more than 12,000 people in North Carolina. But the startups created in the past 10 years account for fewer than 1,000 jobs in Orange County.

Gladdek, who oversaw Durham’s downtown development plan before coming to Chapel Hill, pointed to the growth of commercial “wet-lab” space in Durham as a key element for business investment there. Wet labs are specially engineered facilities that can safely handle chemicals, tissue cultures and other biological materials that are requirements for companies in the life-sciences industry. Low-cost lab space, with shared equipment and short-term leases, has contributed to the growth of biotechnology startups working on everything from more accurate cancer detection to better water purification. Durham has more than a million square feet of off-campus commercial wet-lab space. Chapel Hill has none.

“A lot of those people are locating [in Durham] to have proximity to Duke and Duke faculty and access to well-educated people who will work in those jobs,” Gladdek said. “That’s what we want to see in Chapel Hill.”

A deeper town-gown partnership came together in 2021. Doug Rothwell ’78 (MPA) retired to Chapel Hill after spending his career working for the Michigan Economic Development Corp. and Business Leaders for Michigan. He recognized that Carolina’s status as a research powerhouse was at risk without more off-campus labs and offices where faculty could partner with private companies. “Downtown just really didn’t have the bones to support the University’s aspirations for innovation,” he said.

Last year, Rothwell made his case to Guskiewicz, showing the chancellor a benchmarking study that compared Chapel Hill’s meager commercial partnership space with larger efforts at the University of Virginia; University of California, Berkeley; and UCLA. “We were the only top-five public research university without an innovation district near campus,” said Rothwell, who now chairs the Chancellor’s Economic Development Council and in June will complete his three-year term on the Downtown Partnership board.

The University’s innovation district will launch this fall, when Innovate Carolina moves into the newly refurbished office complex that Grubb Properties is redeveloping at 137 E. Franklin Street and 136 E. Rosemary Street. The old Bank of America tower — “arguably the ugliest building in Chapel Hill,” Grubb said — has been gutted, and its exterior is now sheathed in sleek glass panels. It will house co-working space where entrepreneurs can rent desks or small offices by the month, and where University leaders hope national firms might open offices to be closer to Carolina faculty and recent graduates.

The GAA’s alumni records department helped identify the largest employers of recent graduates, as well as science and technology firms that employ high concentrations of Tar Heels. University officials have made pitches to some of those companies and floated the idea of alumni using the co-working space as a remote office during visits to Chapel Hill.

Grubb’s decision to invest was driven by Carolina’s commitment as an anchor tenant and Chapel Hill’s decision to designate downtown an “opportunity zone,” a special status created by the 2017 federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act that gives large tax breaks to developers for investing in economically distressed areas. “It is a pretty odd anomaly in the world of opportunity zones,” Grubb acknowledged. “And it’s primarily because of all the [zero-income] student base you have inside that zone.”

Nobody imagines Chapel Hill as a rival to Boston or even Durham when it comes to supporting a biotechnology sector, but town leaders are hoping that a critical mass of office workers and researchers will transform East Franklin Street into a more viable venue for the stores and restaurants that define the streetscape.

Proximity the key

The old Bank of America tower, gutted and its exterior now sheathed in sleek glass panels, will house co-working space where entrepreneurs can rent by the month fully equipped desks or small offices and where University leaders hope national firms might open offices to be closer to Carolina faculty and recent graduates. University officials have pitched the idea of alumni setting up shop in the co-working space or having a remote office when they visit Chapel Hill. Images courtesy of Grubb Properties

A recent tour of The Gwendolyn, a smaller Grubb Properties office building just completed a mile from campus in the Glen Lennox neighborhood off of U.S. 15-501, offers a preview of what startup space downtown might look like. Floor-to-ceiling windows illuminate furnished office suites ready for eager young professionals to plop down laptops and work. Each floor includes shared conference rooms, kitchens and common seating areas — “collision spaces,” in industry jargon — where colleagues from different businesses might rub elbows and collaborate on a project.

The more flexible arrangements fit the University’s vision of making commercialization and private-sector partnerships easier for faculty. “The amount of time and resources it takes a young company to go through the real estate process is really challenging,” said Michelle Bolas, who has been at UNC since 2013 and was named Carolina’s chief innovation officer this year. “The easier that is for a faculty member to navigate, the easier we can build a vibrant startup ecosystem in Chapel Hill.”

Bolas pointed to AnelleO, a small firm founded by Rahima Benhabbour, a UNC biomedical researcher. Using 3D-printing technology, Benhabbour developed an inexpensive vaginal ring to deliver hormone and drug therapies. The technology could lead to improvements in women’s health — if Benhabbour can navigate the path from the research lab to the pharmaceutical market. She works out of the University’s KickStart Accelerator in the Genome Science Building, where AnelleO leases a small office and lab space as it continues to refine the technology.

“It’s great because I don’t have to travel off campus,” Benhabbour said. “It makes it a lot easier for me to check in with the company.”

But when AnelleO needs to hire more employees and lease more space, the logistics get complicated. The University’s current startup space is big enough for only a handful of employees, so fast-growing companies have to look for space in Durham or Research Triangle Park.

The planned lab space on East Rosemary Street is designed to put larger-scale facilities within walking distance of campus. BioLabs, the private company that will manage much of the space, already runs similar facilities in Princeton, New Jersey; New Haven, Connecticut; Cambridge, Massachusetts; and Durham. The firm specializes in working with academic researchers, and some Carolina faculty already lease space in BioLabs’ Durham location.

“To be able to go just one block down instead of driving to RTP or to Durham, that will be amazing,” Benhabbour said. “It’ll be so much larger than anything we have now, and I think that will help with attracting talent to Chapel Hill, attracting funding, helping us bring in business leads.”

It will also transform the downtown skyline. The lab and office complex, seven stories of glass and steel set back from the corner of Rosemary and Henderson streets by a small green space, will tower above the storefronts of Franklin Street. “Having the ability to literally just go across Franklin Street and meet the private sector where they are … is just a really, really phenomenal opportunity,” said Grubb, who plans to raze a parking deck and start construction of the building next year.

Developers plan to replace the bank building on the corner of North Columbia and East Rosemary streets with a seven-story apartment building, viewed from the southwest. Images courtesy of Grubb Partners

Nobody imagines Chapel Hill as a rival to Boston or even Durham when it comes to supporting a biotechnology sector, but town leaders hope a critical mass of office workers and researchers will transform East Franklin Street into a more viable venue for the stores and restaurants that define the streetscape. Many Franklin Street businesses were hit hard during the COVID-19 pandemic, when students and faculty were absent from campus for nearly 18 months. Even before COVID, East Franklin Street buildings had long vacancies and high turnover rates. For a span of a few years, the corner of Franklin and Columbia streets had three shuttered storefronts where restaurants such as Spanky’s and MidiCi Pizza used to be.

“We’re very dependent on students, and that creates a lot of challenges,” Hemminger said. “We need more office workers, more adults, more people who are here 12 months of the year. We don’t want to be all bars and takeout restaurants. We want a mix of different things.”

Relocating the UNC Office of Undergraduate Admissions, currently housed in the cramped confines of Jackson Hall on the eastern edge of campus, may help sustain a more diverse mix of stores and restaurants. More than 50,000 prospective students and families visit Carolina every year for a campus tour, but many of them never set foot on Franklin Street. Putting the admissions office in the heart of Chapel Hill will increase the chance those families spend at least part of their time in downtown businesses.

Hemminger said she doesn’t want to lose the small-town character of Chapel Hill or the iconic streetscape of Franklin Street. But given the growth across the Triangle and the ambitions of the University, change is inevitable. “Our downtown is our backbone, and we have to keep it evolving,” she said. “We can’t stay stuck in amber, or we won’t survive.”

Eric Johnson ’08 is a writer in Chapel Hill. He works for the College Board, the UNC System, and occasionally for UNC.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.