No School Is an Island

Posted on Nov. 10, 2017

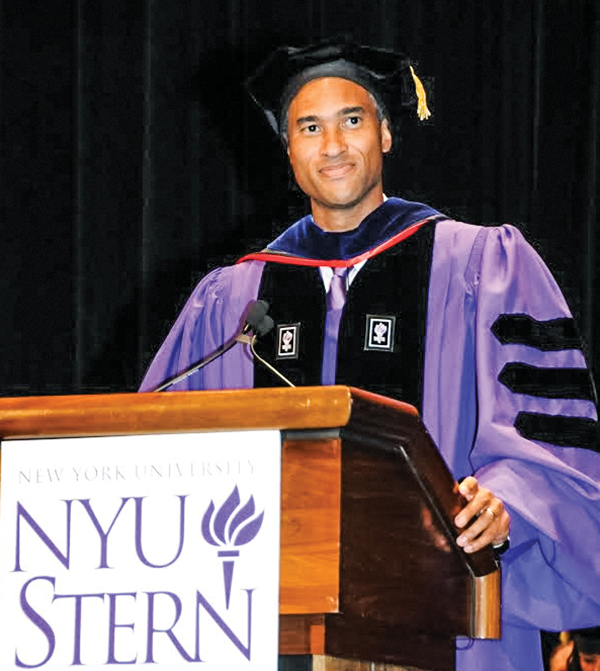

Peter Henry ’91 is Dean of New York University’s Leonard N. Stern School of Business. (Photo by Robin Twomey/Redux)

Peter Henry ’91 took the lessons from the economic mistakes of his homeland to his mission to diversify NYU’s business school.

by Tim Gray

Poverty was an in-your-face reality for Peter Henry ’91, growing up in Jamaica in the 1970s.

At Sunday school, some of his classmates had shoes, some did not. When he’d visit his grandmother in Kingston, he’d encounter Miss Mama, who’d come knocking on the door, begging for a meal. She, too, was barefoot, with tattered clothes, matted hair and a distended belly.

Henry grew up in Jamaica. “It was like Tom Sawyer. We lived on 20 acres, with goats, rabbits and chickens.” He was spared poverty but saw it all around him. (Photo courtesy of Peter Henry)

Henry began to wonder why some people had so much and others so little. And he kept wondering. What started as a boyhood question has become part of the foundation of Henry’s leadership of New York University’s business school, where he became dean in 2010. He was then 40 — the youngest person ever to take the job.

Talk with Henry and you’ll hear how much of his professional life has been devoted to a problem that’s easy to articulate and difficult to solve: What’s the best way to help people, whether developing nations or needy students, help themselves?

Henry is stepping down as dean at the end of this year to take back up his life as a professor and researcher. When he announced the move a year and a half ago, the echoes of his boyhood lessons came through in his answers to the what’s-next questions: “I want to get back to chipping away at that mountain of making better economic policy, especially for the small countries in the Caribbean like Jamaica.”

Michael Manley’s Jamaica

Henry’s parents both earned doctorates in the U.S. and returned home in hopes of aiding their country’s development. His father was a food chemist with Cadbury, the British candy company, and his mother was a plant pathologist at an agricultural research station. This was when Jamaica was led by an impassioned nationalist named Michael Manley.

Growing up, Henry cared as much about sports as he did schoolwork. The family lived somewhat idyllically in the cocoa-growing countryside. “It was like Tom Sawyer,” he said. “We lived on 20 acres, with goats, rabbits and chickens.”

But Manley would become important to Henry’s economic worldview — that while market forces are important, the consequences of individual decisions should not be under-weighed.

Manley, a son of privilege, refashioned himself as a champion of Jamaica’s powerless. His rallying cry was Delroy Wilson’s reggae song Better Must Come, and he famously proclaimed: “Jamaica has no room for millionaires.”

“Peter is a mensch, someone who does the right thing for the right reasons,” says Stan Fischer, then an MIT professor and a former vice chair of the U.S. Federal Reserve.

He befriended Fidel Castro and became an international spokesman for the Non-Aligned Movement of countries that chose to operate outside of superpower-led military alliances, such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. In the context of Jamaica, less than 600 miles from Miami, Manley was thumbing his nose at the U.S.

His audacity made him a hero in the developing world. But it was Manley’s economic policy mistakes that would shape Peter Henry’s thinking.

First elected in 1972, Manley was a democratic socialist who aimed to lead his country for the benefit of the poor. He created government jobs and housing programs and, in hopes of fostering a more self-reliant Jamaica, erected import barriers. He nationalized industries — in particular, taking controlling stakes in the country’s largest producers of bauxite, the ore used in making aluminum and his country’s most valuable export.

Manley’s efforts backfired, badly. Government spending shot up, and tax revenues sank. The government resorted to borrowing from the central bank — in effect, printing money to monetize the deficit. Inflation soared; investment collapsed. While common folk applauded the changes, capitalists didn’t. Manley was unabashed, proclaiming that, if Jamaica’s rich didn’t like his policies, there were five flights a day to Miami.

Cadbury and other multinationals pulled out, further hampering the economy. A shortage of government revenue led to cuts at Henry’s mother’s laboratory. Soon, it was apparent that the school Henry attended would close due to a lack of funding. His parents weren’t rich, but they took Manley’s advice and left Jamaica. Sponsored by Henry’s sister, an American citizen by birth, they immigrated to Illinois, where they had earned their doctorates, and the family settled in the Chicago suburb of Wilmette.

A little football, a lot of books

Henry continued to excel as a student and an athlete, playing football, basketball and baseball. Approaching college, he was recruited by Division I football teams as a receiver. He dreamed of attending Stanford University on a football scholarship, but the school landed more-sought-after recruits. The rejection led him to take a risk that brought him to Chapel Hill.

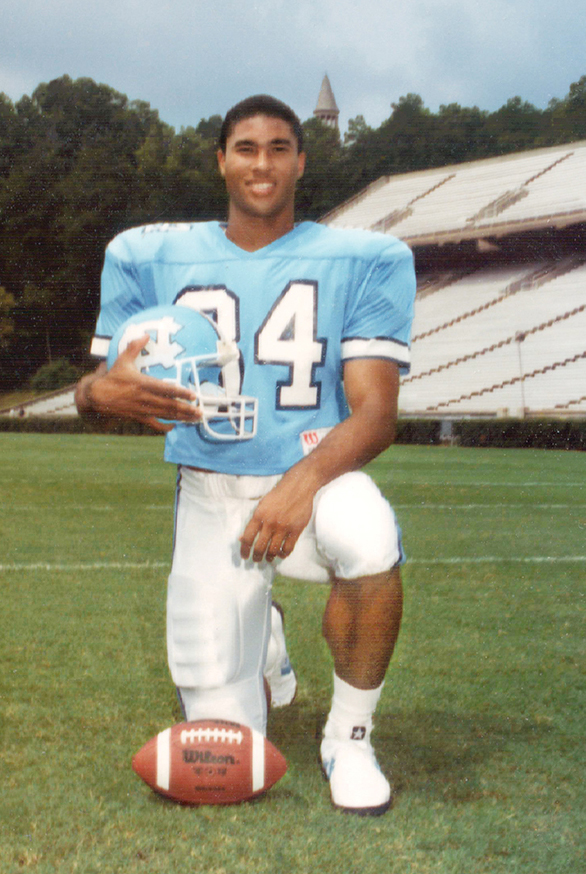

Henry was passed over for a football scholarship at Stanford, but he walked on and played at Carolina. (Photo courtesy of Peter Henry)

Henry’s mother had become wary of the blandishments of college coaches. She wanted her son to decline a football scholarship offer from the University of Wisconsin and interview for Carolina’s Morehead Scholarship. “My mother had a sense I should go and see what the Morehead was about. I trusted her gut, and she was right.” He won the scholarship and didn’t have to forsake his sport: He walked onto the football team and played for two years as a backup receiver. He also was a finalist in the campus’s 1991 slam-dunk competition, losing in the final round to one of his football teammates.

In Carolina’s classrooms, Henry’s curiosity about economics led him to William Darity Jr., then a UNC economics professor and now a professor of public policy and African and African-American studies at Duke University. Darity — son of Sandy Darity ’64 (PhD), the first black person to earn a doctorate at Carolina — became a mentor, sharing articles on development and economic history. The younger man was hooked.

He took aim at the economics doctoral program at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and deferred acceptance while he attended Oxford University on a Rhodes Scholarship.

The MIT economics department is the sort of place where Nobel Prize winners roam hallways and professors take leaves of absence to sit on the president’s Council of Economic Advisers. Even as a student, Henry stood out for his decency and maturity, says Stan Fischer, then an MIT professor and until recently vice chair of the U.S. Federal Reserve. “Peter is a mensch, someone who does the right thing for the right reasons,” Fischer said.

Once rejected for a summer research gig, Henry went instead to St. Kitts and spent the summer studying the role of capital markets in the economic development of small countries at Eastern Caribbean Central Bank.

“I hit the jackpot. That became the foundation of my career. I was asking what would happen if you open your stock market to foreign investment. It just so happened that wasn’t a theoretical issue because developing countries had just started doing that.” After graduation from MIT in 1997, he joined the faculty at Stanford.

Henry was happily focusing on his research when a search firm called him in 2009, asking if he was interested in applying for the deanship at NYU’s Stern School of Business. He wasn’t. But a series of meetings, including with NYU’s then-president, John Sexton, convinced him he should take the job. Sexton, now president emeritus, said he was struck by Henry’s humility. “Peter was self-evidently a team player, going back to his time on the UNC football team. He’d been a star in his academic field, but he didn’t seem to feel an ego need to put himself in the front row.”

Washington Square to Wall Street

Henry took over Stern, known for sending its graduates into finance, at a tough time. Enrollment and fundraising had been hurt by the financial crisis; the school, in Greenwich Village near Washington Square Park, is less than 2 miles from Wall Street. Some faculty and alumni were asking whether its dependence on the finance industry was too great.

He worked to diversify the curriculum beyond Wall Street and looked to recruit scholars interested in globalization.

Henry has raised enough money to take Stern from zero full scholarships a couple of years ago to roughly 50 today. (Photo courtesy of NYU Stern School of Business)

But the achievement of which Henry is most proud is his expansion of scholarships for financially needy undergraduates. He has raised enough money to take Stern from zero full scholarships a couple of years ago to roughly 50 today. “We want to be a place where, if you’re good enough to get in, you can come here, irrespective of your ability to pay,” he said.

“Bringing new people into the conversation — students from places and socioeconomic backgrounds that have not traditionally sent a lot of folks to college — does two things. It brings new problems to the table because the challenges that face the communities of poor, working-class, rural or first-generation students often differ from those of the upper-middle class. Students from underrepresented backgrounds also often bring a new perspective to traditional problems. I felt it was imperative to increase the range of perspectives in our classrooms and thus further increase the excellence of our educational environment.”

Henry came to understand the value of diversity in a student population at Carolina.

“I came from a huge public high school in suburban Chicago where I was one of less than a dozen black students in a graduating class of over 1,100. So when I got to Carolina, I had this extraordinary Ebony magazine experience, getting to be around a critical mass of black peers for the first time since my family left Jamaica. I loved the mutually beneficial learning. My black classmates introduced me to step shows and W.E.B. Dubois; I helped them understand why their roommates liked listening to U2 and The Who. I did, too.

“The diversity at Carolina also taught me a lesson in humility. While my [high school] experience put me at ease in a majority-white environment, I learned that I was a little too at ease, perhaps even a little arrogant. During my first semester freshman year, I was one of a handful of freshmen in my Physics 24 class. After one of the first lectures, a fellow freshman — who happened to be white — named David Wilson asked if I wanted to study together. David was from a small town in North Carolina with an attendant accent and aw-shucks demeanor. I liked him, but what could this kid from Mayberry possibly teach me?

“I demurred his invitation and wound up getting a B+ in the class; David got an A.”

Economists like Henry study how big market forces shape societal outcomes, whether those be the Jamaican economy or the relationship between educational attainment and career advancement. He accepts the field’s orthodoxy that market forces matter mightily, but he also holds fast to the belief that individuals’ choices, good or bad, matter, too. Jamaica, and Michael Manley, taught him that.

In his field of expertise, economic development, a lot of attention is paid to the laws, rights and societal norms that create incentives for people to work and innovate. In this view, what matters most is a country’s history — who settled or colonized it. MIT’s Daron Acemoglu and Harvard University’s James Robinson, in their book Why Nations Fail, argue that countries colonized by the British inherited political and legal systems that better protect private property and encourage initiative than those colonized by France and Spain.

Henry has raised enough money to take Stern from zero full scholarships a couple of years ago to roughly 50 today. “We want to be a place where, if you’re good enough to get in, you can come here, irrespective of your ability to pay,” he said.

As a Jamaican, Henry saw a problem with that argument: His birthplace had been a British colony, and its economy had faltered, due to Manley’s mistakes. That convinced him that policies mattered as much, and maybe more, than institutions. And as an economist, he saw a clever way to show that.

In a paper published in 2009, he argued that institutions couldn’t be destiny because Jamaica and Barbados — two small Caribbean islands colonized by the British — had seen such different economic outcomes.

Their histories were similar. Both were populated mainly by the descendants of Africans who’d been brought forcibly to the islands to cultivate sugar cane. And both, even after declaring independence from the United Kingdom in the 1960s, retained the political systems the British had created.

“Barbados and Jamaica inherited almost identical political, economic and legal institutions: Westminster Parliamentary democracy, constitutional protection of property rights, and legal systems rooted in English common law,” Henry and a co-author wrote in American Economic Review (PDF). “Yet, the standard of living in the two countries diverged in the roughly 40-year period following their independence from Great Britain.”

If anything, Barbados began its independence in more straitened circumstances — it lacked Jamaica’s bauxite. Otherwise, the two countries’ newly free economies started off similarly. In 1960, real gross domestic product per capita was close to $3,400 in Barbados and $2,200 in Jamaica. Forty years later, Barbados had reached about $8,400, while Jamaica was at about $3,200. “Put another way, the income gap between the two countries now exceeds Jamaica’s level of GDP per capita,” Henry and his co-author wrote.

Henry sees the paper, which inspired his book, Turnaround: Third World Lessons for First World Growth, as not just a description of the economic history of two islands but also as a prescription for where countries, developing and developed, should focus. “The institutional argument isn’t very useful to policymakers, and it robs countries of any agency,” he said. “You can’t control who colonized you, but you can control policy.”

Come the end of the year, when he’ll once again be free to pursue his research and policy interests full time, Henry expects he will return to the question of why some places have stumbled economically and which sorts of policies will enable them to close the gap with more prosperous locales — whether those gaps exist between developed and developing countries, within the developed world or even in a single country, such as the United States.

“Somehow, we’ve forgotten that trade, capital flows and immigration are the keys to driving greater shared prosperity — whether you’re in Akron, Ohio, or Accra, Ghana. We need more of those things, not less. I want to get back to advocating for that, and I feel like the best way for me to do that is through my research and teaching — engaging with students, scholars and even the broader public. Thanks to technology, the classroom’s now the world, and the possibilities are endless.”

Tim Gray is a freelance writer based in Bedford, Mass.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.