Partnership and Stewardship

Posted on Jan. 14, 2000As The University of North Carolina begins the 21st century, we should be proud that, because of the special partnership between our campus and the people of North Carolina, Carolina is stronger by any measurement than when we began the 20th century. This relationship distinguishes us from the other great public universities, including the universities of Michigan, California and Virginia. This partnership now spanning over four centuries has permitted the assembling of the needed resources of people, facilities and programs to build a unique public university.

Access to our University by anyone with the credentials to be admitted always has been important. In 1795, UNC’s first provost and presiding professor (later called president, dean of administration and, now, chancellor) were paid from tuition collections, which then amounted to $30 per student.

“The General Assembly shall provide that the benefits of The University of North Carolina and other public institutions of higher education, as far as practicable, be extended to the people of the State free of expense.”

— Article 9, Section 9 of the N.C. Constitution

The recent discussions about increasing tuition to provide needed financial support to permit UNC faculty salaries to become more competitive with peer public and private institutions often confronts the constitutional mandate referenced above. Strangely, some want only to focus on the word ” free” and ignore the word “practicable.” T hose who genuinely are concerned about North Carolina’s college going rate and access must take in to consideration the exhaustive research cited in the above referenced report.

In 1995, our campus was permitted to increase tuition by $400 per student, provided that as much as 40 percent of the funds collected were set aside for need-based financial aid for students who would be adversely affected by such an increase. We have not needed the full 40 percent in any year since the increase was implemented.

“The University of North Carolina is a publicly supported institution. Tuition payments and other required student fees meet only a part of the total cost of the education of students enrolled. On the average, for each full-time student enrolled in an institution of the University of North Carolina System, the State of North Carolina appropriated $8,322 per year in public funds to support the educational programs offered.”

— Statement imprinted on all tuition bills submitted to UNC System students.

Currently, for every $1 a student (or his or her parents) pays in tuition and fees, the state of North Carolina provides nearly $6. This is a wonderful partnership between the state and our students. However, faculty salaries are significantly behind the public and private institutions with which we compete. The quality of the education our students receive is in jeopardy unless we address the growing gap in resources needed quickly.

And the gap is not just in salaries and benefits. There also is a growing deficit in facility needs, particularly the research facilities so critical to attract the next generation of faculty. With one third of UNC’s faculty scheduled to retire in the next decade — at the same time North Carolina will need to accommodate the higher educational aspirations of an additional 50,000 high school graduates — it is crucial that we have salaries, benefits and facilities to compete in the marketplace for the best faculty.

Some want to know how is it that the UNC System has $7 billion in needed capital improvements? (Roughly $1 billion in needs was identified by outside consultants just for our campus.) Others want to know why our salaries are not as competitive as they once were. Still others are concerned about North Carolina’s financial circumstances as consequences of a $1 billion tax cut in 1995, court decisions resulting in significant state funding obligations, and the tragic situation in eastern North Carolina resulting from Hurricane Floyd.

“States that have not focused their investments on needy students and instead pushed low tuition policies for all students tend to have the lowest college participation rates … these data provide strong and consistent confirming evidence that the high-tuition/high-aid model of financing higher educational opportunity works. Private higher education has demonstrated this for many years. Public higher education ought to stop fighting this if it is to effectively and efficiently serve the public interest. … Low tuition for all is by definition an inefficient way to use limited state resources to maximize higher educational opportunity. All students face the same sticker price, which in public institutions is heavily subsidized by state and sometimes local government funds. All students receive similar state subsidies, regardless of whether they need the subsidy or not. The use of limited public funds to keep tuitions low for students who could afford to pay for more or all of their higher education denies these state funds to other students who need help paying college attendance costs.”

— Postsecondary Education Opportunity, February 1999

The 1999 N.C. General Assembly directed the UNC System to conduct an analysis of the competitiveness of faculty salaries and benefits at each of the 16 campuses and further directed that, if any campus was found not competitive, to recommend funding remedies. Interim Chancellor William McCoy ’55 appointed a committee (whose members included GAA Assistant Treasurer Anne Wilmoth Cates ’53, GAA Director Tim Burnett ’62 and myself) chaired by Provost Richard Richardson to prepare a report and make recommendations to UNC’s Board of Trustees; those were then forwarded to the UNC System. After identifying significant funding needs for faculty salaries and benefits, our committee suggested three sources of funding — state appropriations, private gifts and tuition increases.

No one “wants” high tuition. Even if the recommendations of the trustees are approved, our tuition still would be in the bottom quartile among public institutions. And no one wants to remove the principle responsibility for funding our University from the N.C. General Assembly. However, we also hope that no one wants to permit a continued deterioration in our physical plant, a continuing decline in the competitiveness of our faculty salaries and benefits, and a continued decline in UNC’s place in the rankings.

Those who oppose a tuition increase should be challenged to identifY other ways to address our urgent funding needs. And, at least this year, we must acknowledge that it is not sufficient to say that the General Assembly, either through a tax increase or significant cuts in other parts of the state budget, can be the only source for needed funding.

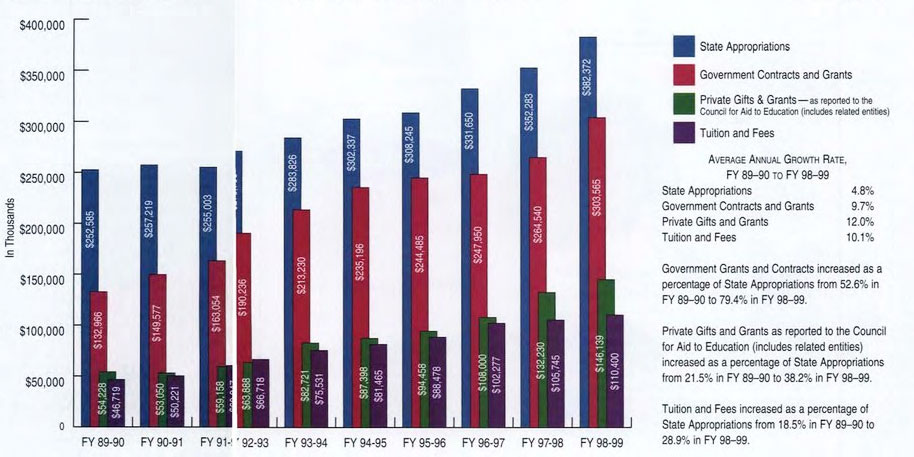

The chart shown here shows clearly the partnership among faculty (as reflected by a dramatic increase in research funding, which in turn has a significant impact on the state’s economy), alumni (as reflected by record amounts of philanthropic giving) and taxpayers (still the University’s single largest source of funding, though proportionately declining when compared with research grants and private giving). Appropriately, the lowest amount of support is reflected in tuition.

Might the 206-year partnership be ending? Does North Carolina no longer find value in a world-class research institution that continues to address the special problems of our state but also is internationally competitive in creating new knowledge? With a boom in enrollment awaiting North Carolina, do North Carolinians want their best and brightest to leave our state to find

a world-class education? Do we really expect that North Carolinians, some of whom could not or did not receive a college education, are prepared to make dramatic increases in their taxes to fund higher education?

a world-class education? Do we really expect that North Carolinians, some of whom could not or did not receive a college education, are prepared to make dramatic increases in their taxes to fund higher education?

In the coming months, these and other questions will be answered. If our most productive and distinguished faculty conclude that too few students and their parents are prepared to pay more for their education; if too few alumni are willing to give back for the value of the Carolina diploma they carry (but for which we paid only a small fraction of the cost); if North Carolina taxpayers, as reflected through their legislators in the General Assembly, are unwilling to view our campus as an investment in the state’s economic future rather than an expense and do not provide funding for salaries, benefits and facilities that permit us to compete with the universities of Michigan, Virginia and California as well as Stanford, Chicago, Emory, and yes, Duke — then the unspoken message the faculty will receive is that, despite their passionate commitment to their students and our University’s historic mission, to excel professionally, they must reluctantly begin to look seriously at the job offers that for years they have ignored. While their compensation may be well above that of average North Carolinians, like other professionals, UNC faculty do not compare themselves with all North Carolinians but to their faculty peers around the world.

We can and we must address our severe funding needs. It is not acceptable to say that North Carolina cannot do something because of Hurricane Floyd’s impact on eastern North Carolina. It is not acceptable to conclude North Carolina cannot do something because of the General Assembly’s tax cut in 1995 that has taken $1 billion out of the state budget. It is not acceptable to allow North Carolina’s most valuable human creation — our University — to deteriorate further.

Alumni and friends can and must do more through our own charitable giving and by insisting that our legislators support our campus. And students and their parents who can also may have to pay more in tuition if the value of a degree from UNC is to remain high. Our state’s economic self-interest requires us to do something now. North Carolina’s children deserve nothing less. Let each of us begin the 21st century by doing all we can to demonstrate the strong stewardship our University has enjoyed for 206 years and to ensure that our special partnership with the people of North Carolina continues.

Yours at Carolina,

Douglas S. Dibbert ’70