Sorcerer’s Stones

Posted on March 11, 2015Obsessed with infinity,

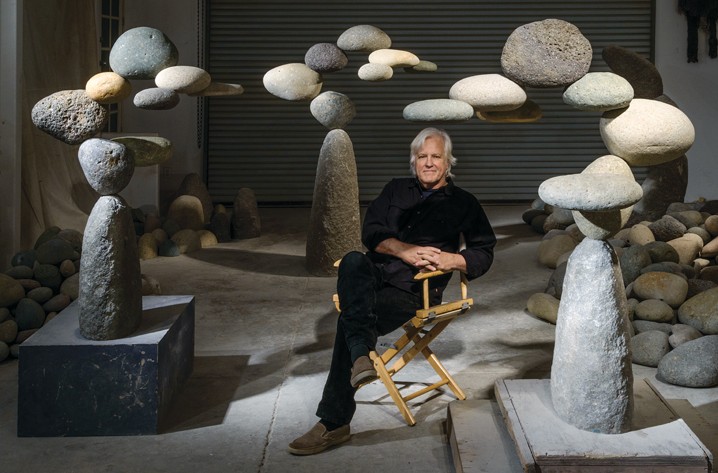

sculptor Woods Davy ’72 has learned

to make natural materials defy natural laws.

Story by Sandra Millers Younger ’75

Photos by Alan Shaffer

Of all the accolades sculptor Woods Davy ’72 has accumulated over the course of his celebrated career, one particular comment means the most to him. It came from a 7-year-old girl, his older daughter, Doniella, in a long-ago conversation with her Saturday morning art teacher.

The class met at the Los Angeles County Art Museum, permanent home to a sculpture of ?Davy’s from 1986. One day, after dropping off Doniella and her sister, Veronica, Davy was walking back from the parking lot to observe the class when he noticed the teacher had gathered her young students around a familiar 7-foot-tall steel-and-stone sculpture positioned outside the museum’s Ahmanson Building, by the main entrance. He could hear her asking their thoughts about it. Then Doniella piped up.

“Here comes my dad. Why don’t you ask him?”

“Why do you think your dad would know?” the teacher responded.

Doniella played it straight, matter-of-fact: “Well, he made it.”

Woods Davy loves to tell this story. He has always valued “good father grades” above critical acclaim. At 65, Davy has boiled life down to three essentials, inseparably intertwined — his family, his work and his obsession with tribal objects.

He’s taken his wife and two daughters all over the world to search for artistic materials and share the excitement of his gallery openings. His evocative, gravity-defying sculptures have been labeled “the poetry of nature.” Meanwhile, his renowned collection of rare African tribal masks feeds his continuing inquiry into the supernatural powers of art.

Into Africa

The entrance to Davy’s home shows some of his collection of masks from Central Africa.

Two distinctive stone sculptures stand sentinel outside Davy’s home and studio in the eclectic beach town of Venice, Calif., assuring visitors they’ve found the right place. One is a graceful column of stacked granite; the other, a cloud of floating stones that flout logic and invite deeper contemplation.

For more than 30 years, Woods Davy has gained international recognition for his finesse in balancing natural elements — wood, metal and stone — in configurations that evoke what some art reviewers have called “a meditative reverence” or “Western Zen.”

Once inside the home that also houses Davy’s studio, however, it’s not his sculptures but an army of African ceremonial masks that commands attention. A host of fantastic faces — part human, part animal, part monster — fill every wall, shelf and horizontal surface.

In the world of tribal art, Davy was first known as a sculptor interested in tribal material; he later became known as a serious collector and scholar. Since falling in love with his first kifwebe (a Central African word for mask) in the late 1980s, he’s accumulated one of the finest collections of these unique tribal creations in existence. Carved from wood and characterized by surprising angles and striations, most were carved many decades ago by the Songye and Luba people of today’s Democratic Republic of Congo. Each mask is as different as the individuals who wore them.

Davy says it’s the nexus of architecture and expression he finds fascinating in kifwebe. He strives for that same marriage of mind and emotion in his own art. But there’s something else, something detectable yet unknowable, that bridges Davy’s twin passions for ancient tribal masks and postmodern stone sculptures. He still feels it each morning when he walks into his studio, a hangar-like space piled high with stones on every side.

“I’m always trying to comprehend infinity in the contemplation of these floating stone sculptures, the way they take you to a place you almost can’t understand. It’s this peaceful feeling that comes from being surprised, seeing these natural elements deny their identity.”

In the world of tribal art, Davy was first known as a sculptor interested in tribal material; he later became known as a serious collector and scholar. Since falling in love with his first kifwebe in the late 1980s, he’s accumulated one of the finest collections of these creations in existence.

Carved from wood and characterized by surprising angles and striations, most of the masks were carved decades ago by the Songye and Luba people of today’s Democratic Republic of Congo.

Davy says it’s the nexus of architecture and expression he finds fascinating in kifwebe. He strives for that same marriage of mind and emotion in his own art.

Song of the sea

In 1986, when Davy and his wife, art museum docent Kathleen Dantini, built this house, Venice was teetering on the edge of gentrification. But the couple saw a community in revival and focused on the benefits of diversity, clean air and a quick walk to the beach.

Doniella, 26, and Veronica, 23, grew up with the ocean nearby. Family vacations centered on snorkeling in tropical destinations. Davy memorized the curve of waves, the sway of seaweed. His impressions tended to resurface in his art.

Davy does the heavy lifting on one of his Cantamar sculpture. The serene, contemplative chord struck by these works makes it difficult to refrain from discussing them in spiritual terms.

“I’ve spent a lot of time snorkeling,” he said, “and I’ve made granite boulder sculptures that appear to be pushed and pulled by the currents, moving in different directions as you’d see something underwater.”

He always has an eye out for elements asking to be made into sculptures. In Mexico, he discovered stones the size of soccer balls tossed onto a remote Baja beach. With each receding wave, he could hear them tumbling over one another. The place was called Cantamar, Spanish for “song of the sea.”

Western Zen

Art critics have been drawn in by the organic appeal of Davy’s materials — stone, metal and wood. They admire his eye for composition, his juxtaposition of tension and tranquility, his “virtuoso display of cantilevered balance.” But most of all they express being enchanted by the effect of his signature Cantamar series — clouds of rounded stones floating in formation like migrating birds, far from home yet certain of improbable destinations.

By contrast, Davy characterizes his previous work as “almost academic.”

“It was a deliberate, very structured way of thinking. This plus this equals something different than the combination. But now I’m flowing, not thinking.”

Wolf Trap is one of Davy’s folded steel sculptures, a 1991 example of one of his earlier styles.

Davy sees every bit of his artistic past as prologue to the Cantamar series. Those early peanut butter years of earnest effort to make art that looked like what he thought art should look like. Those middle years as he developed his first original style — welded steel and natural materials, folded metal, chains and chunks of granite. Even the rewarding years of recognition that accompanied his mature vision — working primarily in natural stone. It all helped him focus his artistic eye while mastering his interest in balancing enormous elements, of stitching stones together with steel rods and industrial-strength epoxy.

Because one day, when Davy focused on a detail of one of his large steel and stone sculptures, he noticed a seamless arrangement of stones that seemed to defy both the power of gravity and their own nature. He knew he’d discovered something special. He could feel it, an inner buoyancy, a stripping away of restrictions. After all, in a world where stones can float, anything is possible.

“It was a pivotal experience,” he said. “All of this rhetoric I’d been saying about the mixture of opposites is a constant reality; therefore, the peaceful combination is a necessity. I said, forget about it. I just like the way these stones are floating, and I want to reduce that to its essence.”

‘Ontological wonder sickness. … It’s a great term to describe that feeling of trying

to comprehend something you’re not equipped to understand.’

Woods Davy ’72

‘We know who you are’

One of the key drivers that brought him to this point, Davy thinks, is a longstanding fascination with the unknowable. Growing up in Washington, D.C., the son of Georgetown real estate agents, Davy pondered scenarios his father posed to encourage his kids’ imaginations. Ideas like: “Just think, if you were in a spaceship, you could keep going and going.”

After Davy broke a knuckle in a fight over lunch money at his rough-and-tumble public school, his parents transferred him to the private St. Albans School. There, as a high school junior, he heard of a concept called “ontological wonder sickness.”

“It’s a great term to describe that feeling of trying to comprehend something you’re not equipped to understand,” he says now, a precursor to his fascination with floating stones and magical masks.

Another lasting benefit Davy took from St. Albans was a Morehead Scholarship nomination. He arrived at UNC in 1968, a conscientious, clean-cut preppy in khakis and Weejuns. Sophomore year? His hair hung past his shoulders; his grades had taken a nosedive; and he was reconsidering his sociology major, thinking about art instead. It wasn’t the best time to run into Mebane Pritchett ’57, then head of the Morehead Foundation. But one day, as Davy ambled down Franklin Street, Pritchett’s car pulled up. “I looked up and thought, uh-oh, and immediately apologized for my grades.”

“That’s OK,” Pritchett said. “We know who you are. You’re going to be fine.”

A simple promise of confidence. It made all the difference.

“I’ll never forget that,” Davy said. “It was such an important event in my life to be believed in by Mebane Pritchett. Here was this man who represented this prestigious scholarship program, this tradition, and he put me at ease. I felt buoyed and bolstered.”

Davy not only pulled up his grades, he got serious about his art. After graduation, he went on to complete an MFA at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and then headed west to his happy destiny as an influential figure in L.A.’s arts scene.

Today Davy is back, in the mesmerizing form of a sculpture that commands the second-floor landing of the Morehead-Cain Foundation offices. A gift from the artist, it’s a wave of suspended stones, an intimation of infinity — an eloquent validation of confidence bestowed, and confidence manifest.

Sandra Millers Younger ’75 is a writer and editor in Lakeside, Calif.

Davy’s Morehead Scholarship came with a dose of forgiveness for his less-than-stellar grades in his first three semesters. His Cantamar 8/19/13 now has a window seat in the Morehead Building. (Photo by Jason D. Smith ’94)

See more of Davy’s work at woodsdavy.com.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.