Supreme Confidence

Posted on Nov. 10, 2017

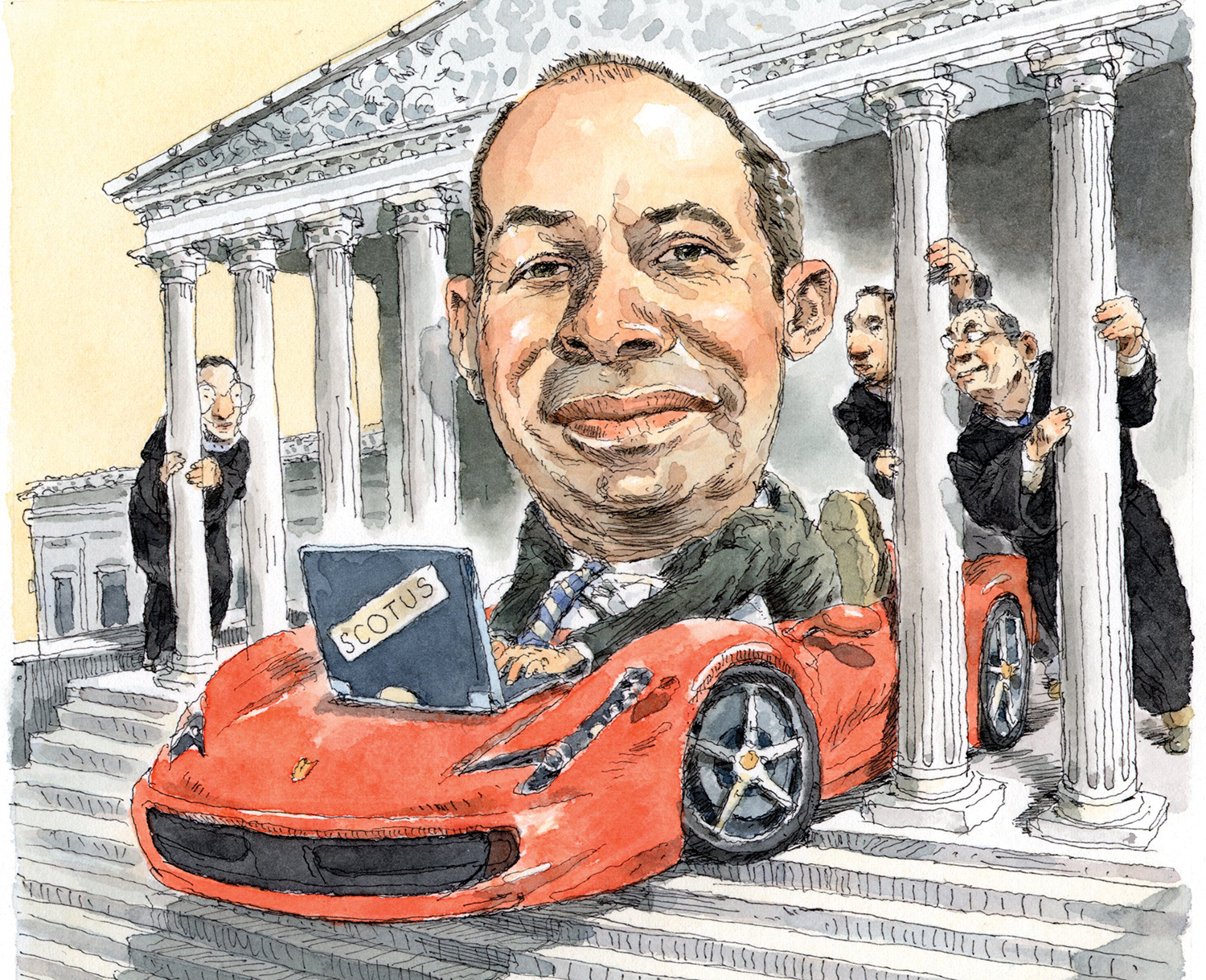

Goldstein’s closeness to the Supreme Court — and the court’s familiarity with his work — are reflected in an illustration from a 2012 profile in The Atlantic. That’s his Ferrari he’s driving down the court’s sacred steps as justices look on warily. (Illustration by John Cuneo)

By the time he got out of the law school he lucked his way into, Tom Goldstein ’92 knew he wanted to go where few ever do — to argue before the nation’s highest court. But his most important work may be the telling of it.

by Elizabeth Leland ’76

At the Supreme Court building in Washington, on a busy summer morning in 2012, a slightly built, balding attorney in a pinstripe suit and silver tie began reading through the court’s just-released decision on the Affordable Care Act.

His calm demeanor belied a relentless intensity.

Barely a minute passed before CNN and Fox News announced that the court had struck down Obamacare. Tom Goldstein ’92 kept reading. Other lawyers, reporters, even White House officials were looking to Goldstein’s law blog for the news from the court, and he wanted to make sure his team got it right.

“Parsing it ASAP,” his wife, Amy Howe ’92, reassured readers of SCOTUSblog, named for the acronym of the court. A minute later: “It’s very complicated, so we’re still figuring it out.”

Finally, at 10:10 a.m., two minutes after the networks got it wrong, Goldstein got it right: “So the mandate is constitutional. Chief Justice Roberts joins the left of the court.”

By the end of the day, the blog was visited more than 5 million times and Goldstein was being celebrated as its creator and publisher. It was an unprecedented role for a lawyer.

Just 13 years earlier, he argued his first case before the Supreme Court at the inexperienced age of 28 — “the legal equivalent of lacing up for the Yankees,” The Washington Post wrote at the time, “without ever having swung a bat in the minors.”

He not only was making news at the nation’s highest court, he was reporting on it.

Tom Goldstein ’92, a Washington attorney and author of SCOTUSblog, stands outside the Supreme Court building.(Steve Ruark/AP Images for Carolina Alumni Review)

Goldstein, 47, is now considered one of the top Supreme Court litigators and SCOTUSblog the go-to source for news and analysis about the court among lawyers, the media and, some say, the justices themselves.

That would be a remarkable achievement for any member of the bar. But Goldstein isn’t just any member. An outsider, he barged his way in with a brash mix of legal savvy, marketing and irreverent YouTube videos. He followed none of the time-honored prerequisites to cornering cases before the court. He didn’t go to Harvard, Yale or Stanford. He didn’t clerk for a Supreme Court justice. He didn’t work in the Office of the Solicitor General. He left Chapel Hill with a degree in political science and graduated from American University’s Washington College of Law three years later.

Harvard law professor Richard Lazarus remembers watching “this young guy” argue one of his first cases. Lazarus noticed Goldstein because of his age. “I paid attention,” he said, “because he was good. He was fast on his feet and well-prepared.”

But as brilliant as his oral arguments may be, Lazarus believes Goldstein’s legacy lies with the blog. “It is a genius contribution to the Supreme Court, an incredible resource and a public service. Anyone who practices before the Supreme Court goes to SCOTUSblog. That was an amazing contribution, both for the public and for Tom’s self-worth.”

The hidden knife

To understand how Goldstein came to excel in the exclusive stratosphere of the U.S. Supreme Court, it helps to revisit Chapel Hill in the early 1990s.

Cori Dauber ’84 (MA), an associate professor of communications, remembers Tommy Goldstein as the most naturally gifted debater she’s ever coached. He presented himself to opponents as “just a boy from Irmo, South Carolina,” soft-spoken and with an infectious grin. But behind that pleasant facade, Dauber knew to “watch for the knife in his hand.”

“He’s going to beat you through hours of hard work and by thinking, finding a strategic way to get at you.”

If Goldstein quit fast-talking like other debaters and approached the judge for “a fireside chat,” Dauber knew they had won. “I’ve never seen any other debater do this. He would say, ‘Now listen, here’s how I see it.’ It was actually like a conversation. He was really something.”

He was such a phenomenon, Dauber said, that observers sometimes credited Goldstein with the team’s success. “He was always quick to say it was a team proposition. He’s caring and looks after the people in his orbit and is funny and charming and all of those things. You could watch him all day but never actually see the knife in his hand.”

Sequestered

On a Sunday in April, Goldstein secluded himself in a 10th-floor suite at the Park Hyatt Washington hotel. For two days before every Supreme Court appearance, he leaves home to focus.

He was dressed casually but fashionably in faded jeans, a crisp blue buttoned-down shirt and black dress boots. On one wrist, he wore an art deco Lecoultre Reverso watch, which he swiveled around and around without actually looking at the time. Beside him on the coffee table was a yellow legal pad scribbled with notes.

In stories from his younger years, Goldstein came across as larger than life, dabbling in high-stakes poker and once shipping a Ferrari to Las Vegas for a drag race. In person, he’s soft-spoken and self-effacing. He gave up poker. He traded the Ferrari for a Tesla P100D (still fast, but with room for the kids). He quit posting YouTube spoofs about his work. These days, most of what he talks about are legal briefs and oral arguments.

“I think most people,” he said, “would find what I do boring.”

That evening, Howe planned to bring their daughters down for dinner from their home in Chevy Chase — eating together is a family commitment they rarely forfeit, not even for the Supreme Court. But other than a rare break for an interview, at the Hyatt there were few distractions.

“When I left home last night, the dog started throwing up and my daughter was sick so it was just good fortune that I had separated myself, and then I’ll be back home on Monday,” Goldstein said. “Now it’s just a question of putting it all together, refining the answers, filling in all the little holes of what I don’t know. That sort of thing. … I’ll learn things until the last possible minute.”

Carolina said no

At Carolina, Goldstein brought that same intensity to debate, often at the expense of his courses. “I never went to class. Amy got me through college. I would take the same classes as her. She would go and I would borrow her notes. She graduated with the highest honors.”

Howe, he said, was a superstar.

Amy Howe ’92 worked a full-time law job while Goldstein represented clients for free. Now she reports for the blog while he devotes himself to his practice. (Steve Ruark/AP Images for Carolina Alumni Review)

“It was a running joke in college,” Howe said. “We were both poli sci majors and there was one class we both had to take our senior year, ‘Introduction to Sociology.’ Tom would parachute in once in a while and make some profound statement. I remember I got an A-minus on the exam, but he got an A with my notes. It was so unfair.”

Although he had no plans to specialize in the Supreme Court, Goldstein had wanted to be a lawyer — his mother’s profession — since he was young. But he failed to factor in how mediocre grades might affect his chances of getting into law school. UNC rejected him. Five other schools never even processed his application because he neglected to send them his LSAT score.

“I got lucky,” he explains about what happened next. His stepmother’s cousin knew the director of admissions at American University’s Washington College of Law. Goldstein got into the evening program, and by the time school began, a seat opened in the regular program. Howe was working on her master’s in Arabic studies at Georgetown University and would later go to law school there. They married in 1994.

Goldstein’s infatuation with the Supreme Court came during his first two summers in Washington. He interned for NPR legal correspondent Nina Totenberg, gathering statistics about the voting patterns of potential new justices. She introduced him to the dynamics of the institution, the personalities of the justices and the power of the perfect sound bite. Howe would later intern for Totenberg, too, while studying for the bar. The couple named their oldest daughter after their mentor.

By the time Goldstein graduated summa cum laude in 1995, he had decided to devote his career to practicing before the court.

He just had to figure out a way how.

He began by refining a technique for identifying potential cases. He was working for the Jones Day law firm, assigned to find “circuit-splits” — cases in which federal appeals courts ruled in different ways on legal issues, making the cases more likely to be accepted for review.

Goldstein added dozens more variables to the standard search algorithm and soon identified four promising cases. But as a junior member of the firm, he had to

hand them off to more experienced lawyers. When he discovered a fifth case, he thought he should argue it himself. His bosses thought otherwise. If he followed their advice, Goldstein figured he would keep plugging in the trenches for years before he got his break.

So he quit the firm and soon 28-year-old Tom Goldstein was standing before the nine justices of the U.S. Supreme Court.

It was not only the first time he had argued before the Supreme Court. It was the first time he had argued a case in any court. “Is the diminutive, moxie-blessed Goldstein ready?” The Washington Post posed.

It turned out he wasn’t.

“We got destroyed in that case, nine to zero,” Goldstein said. “I was very much a baby lawyer.”

“He was never bad, but in the beginning I would guess you’d have to say he was snotty in his position, and they wanted to take him down a peg. He was young. He was brash. He talked too fast. He had a little bit of an attitude, and all that changed in the course of his making his first 10 arguments. He got really good.”

– Nina Totenberg, NPR legal correspondent

Knowing what he knows now, he said he would argue it differently. “I’m arguing from the wrong perspective, trying to persuade the whole court about the whole case, rather than persuade one or two people about one or two strong points. I just didn’t really know what I was doing.”

His next case, he won. He had converted the third bedroom of his house into an office and began cold-calling potential clients. He offered to argue their cases for free. The exposure, he believed, would be worth it.

“You’re trying to give the impression that you’re qualified, which was debatable. I would tell them, ‘I’m very interested, and I’ll do the work for free.’ I was approachable, nonthreatening, collaborative. I didn’t have a lot to say about why I could do a good job.”

Cold-calling clients was unheard of then. One justice reportedly dismissed Goldstein as an “ambulance chaser.” Chief Justice John Roberts was still practicing law at the time and scoffed at the practice. “If I’m going to have heart-bypass surgery, I wouldn’t go to the surgeon who calls me up,” Roberts was quoted as saying. “I’d look for the guy who’s too busy for that.”

“It was incredibly controversial in the beginning,” Goldstein recalled. “I stood for things that they didn’t like. I think they were very comfortable with an elite Supreme Court bar. I didn’t know enough to care. I was so completely on the outside, that the acceptance of this group meant nothing to me.”

In his first eight cases in his first three years, he made a combined $8,000. “It was the only way to get from there to here. I had to make it happen.”

He now charges $1,250. An hour.

From nobody to Jeopardy!

Totenberg, who has covered the court for 42 years, watched Goldstein mature and improve. They remain close friends. “He was never bad, but in the beginning I would guess you’d have to say he was snotty in his position, and they wanted to take him down a peg,” she said. “He was young. He was brash. He talked too fast. He had a little bit of an attitude, and all that changed in the course of his making his first 10 arguments. He got really good.”

Goldstein is credited with expanding the bar, and lawyers routinely cold-call clients, even at big firms. Except Goldstein doesn’t; clients now come to him. He also helped establish Supreme Court litigation clinics at Stanford and Harvard, and he still teaches at Harvard.

Legal Times named him one of the “90 Greatest Washington Lawyers of the Last 30 Years.” In 2010, the National Law Journal named him one of the nation’s 40 most influential lawyers of the previous decade.

He’s the superstar now.

But underneath his three-piece suits, he remains a bit of a renegade. “I think people who do what I do take themselves way too seriously,” he said.

“You’ve got to understand,” NPR’s Nina Totenberg said, “he’s a quintessentially decent person as a human being. When somebody is as smart as he is, there’s always the chance he will lose that sense of personal decency and become completely obsessed with himself.” (Steve Ruark/AP Images for Carolina Alumni Review)

In 2015, he joined Totenberg in a videotaped play-by-play commentary for NPR after oral arguments about state bans on same-sex marriage. They deftly took turns explaining what happened, and Goldstein appeared both well-versed in the law and comfortable before a camera.

After they finished, but with the video still running, Totenberg turned to him and said:

“You look very dapper.”

Eyeing the oversize microphone in his hand, Goldstein retorted: “I feel very phallic.”

“The thing about Tom, you’ve got to understand, is he’s a quintessentially decent person as a human being,” Totenberg said. “When somebody is as smart as he is, there’s always the chance he will lose that sense of personal decency and become completely obsessed with himself and all that. And that didn’t happen to him. I give him a lot of credit for that. I give her [Amy Howe] even more.”

Totenberg calls Howe “the leveler.” In the same way she lent Goldstein her notes at Carolina, Howe worked a full-time law job while he represented clients for free. She’s now primary caretaker of their daughters and reports for the blog while he devotes himself to his practice.

“We’re a good team,” Howe said.

Said Goldstein: “I wouldn’t have time to do what I do without all she does with the family and the blog. And my law practice makes her job possible. So each of us contributes equally to the success of the other. … The only time we’ve had a problem is when there’s been a hierarchy. We figured that out so we’re never in an environment where one reports to another.”

They started SCOTUSblog in 2002, when both were practicing law. They did it for the same reason Goldstein took cases pro bono: If they were viewed as experts on the court, they thought that might draw in clients. Few clients found them because of the blog. But after 15 years, 100,000 or more people read SCOTUSblog on any given day, and TV news shows regularly turn to Goldstein and Howe for expert analysis.

Goldstein estimated he spends half a million dollars each year subsidizing the website but said it’s “the most important thing for my professional stature.” Howe agreed. “I think of SCOTUSblog as my beach house,” she said. “It’s expensive. But we feel like it’s a public resource, and it’s too much fun to stop.”

Howe also has argued before the Supreme Court but now focuses on the blog, covering the Supreme Court and Congress — and loving it. “I can’t believe that my job is to get up in the morning and go down to the Senate and live-blog the hearings,” she said. “And in the breaks, we take turns in the NPR booth with Nina Totenberg. … I’m up there hanging out with her, going on radio. I have no complaints. This turned out so much more fabulous than we imagined.”

Earlier this year, they got an unexpected shout-out while flying with their two daughters to Los Angeles, where they own a condo.

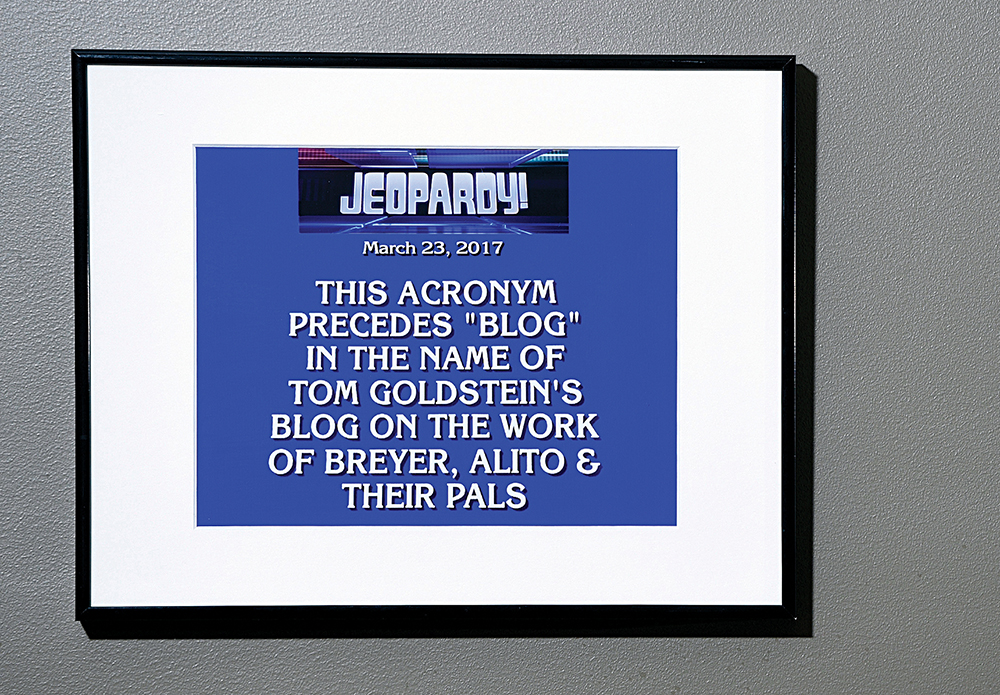

The Jeopardy! moment is captured in a picture frame in Goldstein’s office. (Steve Ruark/AP Images for Carolina Alumni Review)

“Hope you all saw this,” one of many emails announced. Attached was a screenshot from that night’s Jeopardy! television game show.

The category was “Newer Words and Phrases.” The answer for $2,000: “This acronym precedes ‘Blog’ in the name of Tom Goldstein’s blog on the work of Breyer, Alito & their pals.”

A contestant named Robin asked the correct question.

“That was so bizarre,” Goldstein said. “Someone said you get on Jeopardy! and you make The New York Times crossword puzzle, and you’re done.”

Goldstein is not yet done.

‘More mythology than real’

At an afternoon session of the Supreme Court in April, he strode to the front of the courtroom, shook hands with the opposing counsel and took his seat.

Behind him, spectators whispered, a low hum throughout the hallowed marbled chamber. Goldstein appeared lost in thought, the fingers on his left hand absent-mindedly making circles around his closely cropped beard, his mouth silently forming words. Howe, who blogged about Neil Gorsuch’s first day on the court that morning, took a seat in the spectator section to watch her husband’s argument. She doesn’t write about his cases; Columbia Law School professor Ronald Mann covered the hearing for SCOTUSblog.

Goldstein was up against Paul Clement, a former solicitor general who is considered a leading contender for justice if there’s another opening under President Donald Trump. “One of the things I love about what I do is that the people on the other side that you’re dealing with are super talented,” Goldstein said. “They push you. You cannot sleep on any case. The other side is going to make all the best arguments that can be made, in the best way they can be made. It really causes you to up your game. I find other places where you can just wing it very boring.”

To most tourists in the audience, the issues in California Public Employees’ Retirement System v. ANZ Securities probably seemed boring. The case centered on the time limit for filing class-action securities lawsuits. As Totenberg later reported, it was one of three cases that day that “involved technical and convoluted points of law that, to say the least, are not made for easy or interesting translation.”

Goldstein represented the plaintiffs. “I like the puzzle of it,” he said. “The questions that get there don’t get there unless there are two possible answers. Working through the puzzle and coming up with the best version of our side of it, I do find a lot of fun.”

A buzzer sounded and the justices filed in past red velvet curtains and took their seats at the raised mahogany bench. Goldstein stood up, and all eyes turned to him.

He said he’s never nervous — “it’s one institution I really get” — and he appeared relaxed that afternoon, his hands folded casually on top of the lectern. He has argued 40 cases before the court. Only three lawyers in private practice have argued more. “All the things said about a Supreme Court argument are more mythology than real,” he said. “As long as you’re respectful and prepared, you’re fine.”

Promptly at 1 p.m., the hearing began.

“Mr. Goldstein,” Chief Justice Roberts intoned.

And the boy from Irmo, S.C., launched confidently into the first of two oral arguments he would give that week: “Mr. Chief Justice, and may it please the Court. …”

Elizabeth Leland ’76 is a freelance writer based in Charlotte.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.