The Strike: When Social Justice Went From Academic to Real

Posted on April 26, 2019

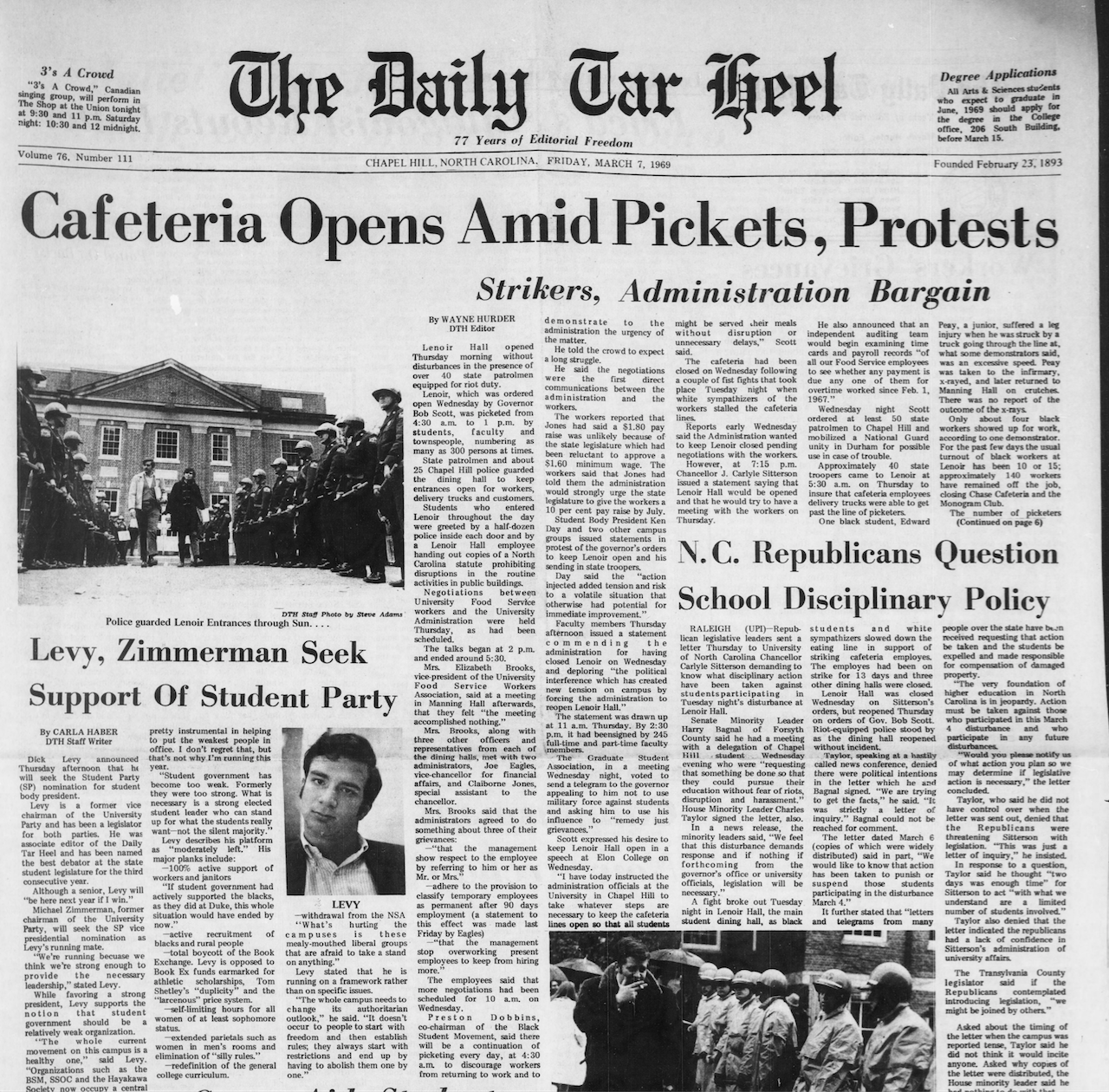

On March 6, 1969, Gov. Robert Scott sent state troopers for the reopening of Lenoir Hall. Student support for the workers was strong. (Virtual Museum of University History)

The administration was aware that the University’s food service workers were deeply unhappy before the workers’ complaints were aired in October 1968. The food service by then was in trouble, and its management was under pressure to get the most for the least in terms of money and shift scheduling. Complaints were met coldly in a tight job market.

To cooks, servers and dishwashers, this looked not like efficiency but disrespect. Sometime in the four months between October and late February, the people who refined the fuel that kept students going could go on no more. Fed up.

“Seventeen employees of the Pine Room ‘took the day off’ Sunday,” The Daily Tar Heel reported, “and told the management they would not return to work until it has done something about a list of grievances they had presented to the University Food Service last fall.”

Specifically, the workers set up for the meals for Feb. 23 and then sat down at the dining tables. The next day, 25 more walked out of Lenoir, the dining hall that also housed the Pine Room.

The crisis was on the front page of The DTH for months.

The list was long, and it was built in cooperation between servers and served — the fledgling Black Student Movement helped shape it. The actions the grievances spawned would be disruptive and would resurface months after the gulf apparently had been bridged. The cafeteria workers were forceful negotiators on their own behalf, but they were never without the strong support of Carolina students.

Preston Dobbins ’69, co-chair of the BSM, called for a boycott of all campus eateries, which were managed by the University. Among more than 10 demands were pay raises and pay grade improvements — some had been denied raises that they were due; time and a half for overtime; hiring of African-American supervisors; an organized means of negotiating with management; and upgrades in general working conditions.

More than 140 workers walked, and UNC closed the Pine Room, Chase Cafeteria and the Monogram Club.

Problems on the business side had been building. Food service was becoming a nonsustainable enterprise. Costs were rising, and students were less inclined to take just what the dining halls offered, venturing to Franklin Street for more variety. Business in Lenoir dropped precipitately from 1966 to 1968. Soon after Chase Cafeteria opened in 1965, it was apparent students weren’t going to provide the anticipated volume — it had a $100,000 deficit after three years. The Pine Room also was running at a loss. And state regulations didn’t permit the University to transfer money from one administrative operation to another that needed help.

On Feb. 27, students and others stopped two delivery trucks bound for Lenoir; the drivers honored the strike, which was headed into a tense month of picketing and boycotting of campus dining. The BSM and the workers didn’t seem to be making progress getting the administration to negotiate. The Student Legislature came out in support of the workers.

Some of the workers began to fear being fired and went back to work. The BSM and the workers set up headquarters in Manning Hall, recently vacated by the law school, where they took donations for unpaid workers and cooked fried chicken dinners to compensate for the closed halls.

The BSM led a forced slowdown of service in Lenoir on March 3 that led to scuffles the next day. Supporters of the workers, said to be in equal numbers black and white, overturned tables and threw chairs around. Police in riot gear moved in and shut down the hall.

On March 5, Chancellor Carlyle Sitterson ’31 (’32 MA, ’37 PhD) and UNC System President William Friday ’48 (LLB) met with Gov. Robert Scott. They argued against a large police presence. Then Scott said in a speech at Elon College that day, “I have today instructed the administration officials at the University in Chapel Hill to take whatever steps are necessary to keep the cafeteria lines open so that all students might be served their meals without disruption or unnecessary delays.”

On March 6, Lenoir reopened with helmeted, baton-carrying state troopers and Chapel Hill police lined up at the front door. Scott had National Guard units standing by in Durham.

On March 7, the two sides negotiated. Elizabeth Brooks, one of the leaders of the workers, said they were promised that management would use respectful terms to address workers, that temporary employees would be classified permanent after 90 days and “that the management [would] stop overworking present employees to keep from hiring more.”

By the time rising tensions spilled into the public, the BSM, barely a year old, was at war with Sitterson, unsatisfied with his response to 24 demands (mostly academics-related) they had presented in December 1968.

On March 11, Sitterson told 2,000 people packed into Memorial Hall of his concerns that the demands be considered carefully; he also spoke of “preserving traditions” and the consequences of resorting to force, interference with public buildings and subordinating teaching duties to justice pursuits. The workers, their leaders and their backers in the student body were unmoved.

Under increasing pressure from the state’s lawmakers and the public to resolve the conflict, Scott ordered state troopers to close Manning Hall. The students evacuated ahead of them.

The next day, Sitterson told the students that UNC was meeting demands and would address workers in respectful terms, pay back overtime, hire a black supervisor, study reclassifying jobs and guarantee two Sundays off a month. The food service’s director was reassigned.

A week later, the governor ordered the $1.80-per-hour minimum the workers had demanded. They went back to work.

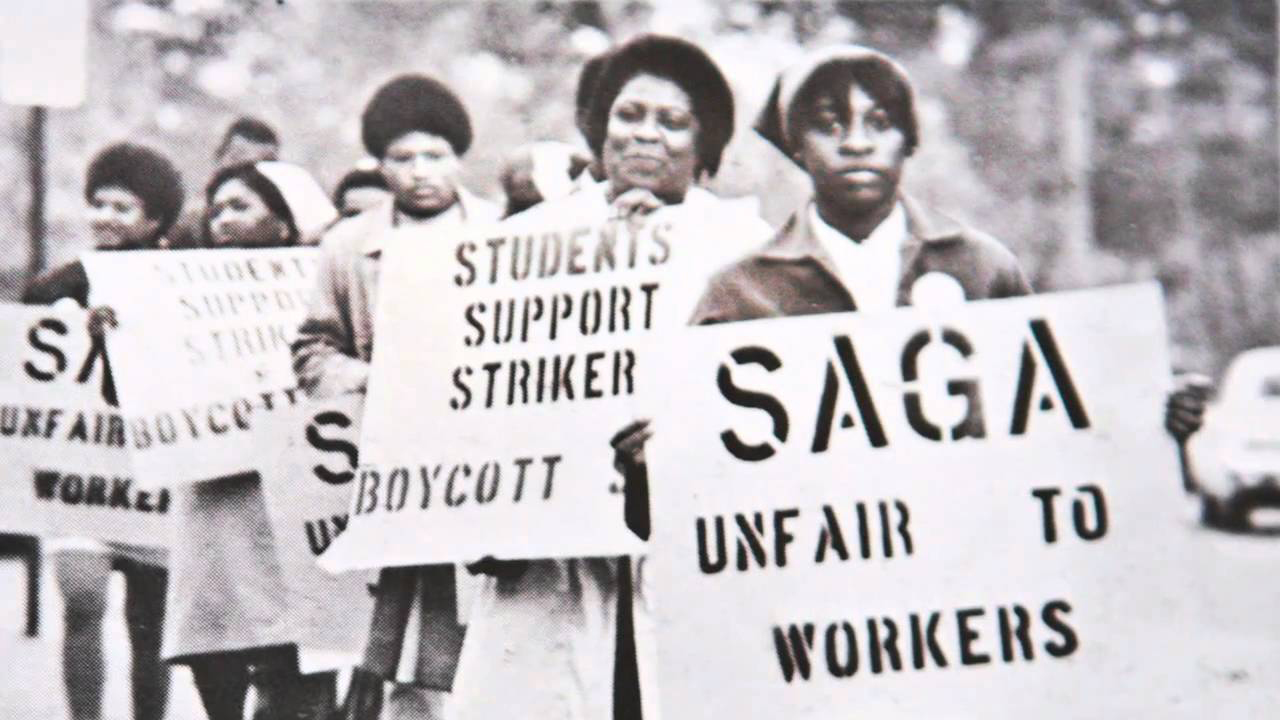

After the University settled with the food service workers in spring 1969, it got out of the cafeteria business and contracted with SAGA Food Services, a California company. The workers, unhappy with the way SAGA treated them, went on strike again in November. (Virtual Museum of University History)

In the final weeks of the school year, UNC gave up running campus dining (except at The Carolina Inn and the hospital) and brought in SAGA Food Services, a California company that ran food service at some 300 institutions.

That became a ticket for more trouble between management and the workers — the cafeteria drama often is remembered as a spring 1969 event, but “strike” was heard again that fall.

In early November, SAGA fired 10 workers who were understood to be promoting union organizing. Workers struck the next day, and only Lenoir and Chase remained open. Organizers said the workers had formed a nonaffiliated union with 75 dues-paying members; they said that workers were being forced to “double-up” to meet management demands and that the promised minimum pay had not taken effect.

Full-time workers voted 94-26 later in the month to organize under the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees. Mediation already had started with SAGA. The University administration largely stayed out of it.

On Dec. 4, violence broke out at Lenoir between police and pickets, described by The DTH as students; three people were sent to the hospital, and several were arrested. One might wonder how close it came to being much more serious: The pickets were not giving ground, and the police were seen gathering rifles.

“The police officers asked them to disperse twice,” Chapel Hill police Chief W.D. Blake said. “They failed to do so. If there is danger of officers being assaulted, you unlock all your weapons. The way things have occurred elsewhere, there could be snipers.”

On Dec. 8, a settlement was announced. The DTH reported: “Terms of the contract provide for job classification, seniority, a minimum four-hour day, 10 paid holidays, 10 sick days leave, unemployment compensation, a union bulletin board and an end to split shifts.”

The contract was set to expire June 30. In January, SAGA announced that at the end of the semester, it, too, was giving up on food service at Carolina.

— David E. Brown ’75

“Service, Not Servitude,” an exhibit on the crisis, will be open until May 31 in the N.C. Collection Gallery in Wilson Library.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.