This Debate Is Nothing New

Posted on April 20, 1993From the University Report (published by the GAA 1970-94)

Note: In preparing a column regarding the concern that Carolina may place too little emphasis on teaching while too greatly valuing research, I came upon the following column in The Fayetteville Observer-Times by contributing editor Roy Parker Jr. ’52. Parker says it so well — better than I could. His column first appeared in the Feb. 25 issue of the Observer-Times. Parker currently serves as vice chairman of GAA’s Publications Advisory Committee and is a member of our University’s Board of Visitors. He has served as vice president of the GAA and has received the University’s Distinguished Alumnus Award.

Yours at Carolina,

Douglas S. Dibbert ’70

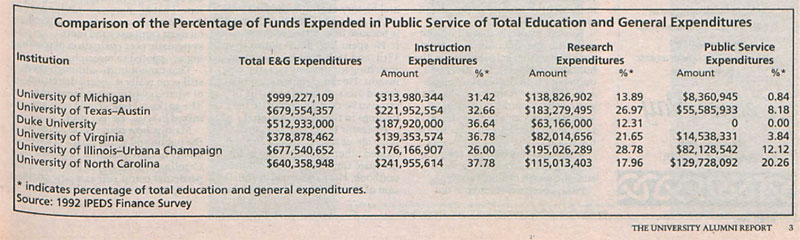

The chart below was not part of Parker’s column, but it demonstrates the significant percentage of our resources that Carolina devotes to instruction and service.

The perennial debate over what is more important on a college or university campus — teaching or research — has heated up again in North Carolina, thanks to a bulky new study by the N.C. Center for Public Policy Research.

As would be expected these days, the report is critical. It surveys the 16 campuses of the University of North Carolina System and concludes that, overall, teaching is not being rewarded as much as it should be.

Another outfit not anything as careful or believable as the Center for Public Policy Research, the right-wing John Locke Society, had earlier made the same charge in a report that was mainly aimed at the big research campuses of Chapel Hill and N.C. State University.

The former campus has ever been the target of right-wingers. It used to be they were”communists.” Now they are those nasty”researchers.”

And, of course, you might not remember it, but the left-wing students at the University of California were making much the same statement 25 years ago when they literally stormed the offices of the administration, calling for” student power.” A major complaint was that stodgy old professors were more interested in their researches than in the folks out there whose tuition paid their salaries.

From all sides

Right, left and center. That means either that the complaint is universal or that the school must be doing something right.

The basis of this complaint is as old as the Middle Ages, when students in Paris or Oxford or Bologna would periodically storm the classrooms, pelting the masters and the dons with offal in protest of their supposed incompetence or irrelevance.

The fact is, a university is both. It is teaching, the imparting of all the great truths and the mountains of information that civilization has searched out since that first ancestor struck the flint on the rock and puzzled over the spark.

It is also research, the vital hunt for more information, for new truths that can correct old errors or open new corridors of thought that will then lead on to even more information, new truths and on down the road.

In North Carolina we have decreed that the University of North Carolina and North Carolina State University are “research universities,” which means what it says.

In Chapel Hill and Raleigh, bright men and women with doctorates and brains bigger than those of us ordinary human beings are doing the most vital work of civilization.

Why research matters

Just a single example from recent months.

Friends of mine celebrated the birth of their first grandson — and learned that the little fellow has cystic fibrosis, a relentlessly debilitating respiratory condition for which there currently is no adequate medical solution.

Almost in the same week came the news that researchers at Chapel Hill had won the race with researchers elsewhere in devising a “test mouse” that offers promise for a really significant breakthrough in defeating the effects of cystic fibrosis. Even more awesome, rather than wait to get a patent on their invention, the researchers tossed it into the public domain so it could be used quickly in the fight to save lives like that of my friends’ grandson.

You can multiply that all up and down the line, not only in medicine but also in other sciences and in the humanities as well. The glory of a university is in the breakthroughs achieved by its resident brains. And you can bet that the quality of research is what gives a university its rank among the human treasures of the world.

It is brains at work, not tongues wagging in classrooms, that measure the worth of a university.

Now, of course, research is not worth a fig unless it is imparted. Teaching indeed is the inseparable other side of the higher educational coin. Many of our campuses are basically dedicated to shoveling out the facts to students whose higher educational goal is mainly occupational.

The fact is, however, that only those brains big enough to be forever researching for new truths and new information can also be bright enough to be good teachers. That is as true on a small campus as on a large one.

I think of the great teachers of 45 years ago, and the exemplar who still stands out is the late Hugh Lefler, professor of history at the University of North Carolina. He held undergraduate classes spellbound with a subject that should have been dull as a froe — the colonial history of North Carolina.

The reason he could teach it well is because he practically invented it. He spent long hours poring over 17th- and 18th-century documents, searching for the new fact, the new insight. He ran graduate students ragged pressing them to do the same so he could incorporate their findings in the course material.

Professor Lefler sparked new ideas about research areas and nagged other students to do it. In his spare time he co-authored the textbook. His gargantuan enthusiasm of his subject made this little slip of a man a 900-pound gorilla when he stepped up to the lectern.

Greatness still shows

Of course, there are individuals who can cavort well before a”class without ever having done much but master the standard material. There are plenty of comedians on television who can do the same thing. Often these people receive big votes when students are asked to name their favorite professor. But even the most dense undergraduate knows when there is greatness up there at the lectern. And nearly always the truly great teachers are also giants of research.

The study by the N.C. Center for Public Policy Research has a standard answer to the supposed problem. That is, more rewards for good teaching than currently are offered on most campuses and more systematic peer evaluation of teaching as opposed to research.

That cannot hurt — although there still is no really standard definition of what constitutes good teaching. The snake-oil types could well get mixed in with the real stuff.

Mainly, however, this is a plea to the public and to the Board of Governors of the University of North Carolina System not to buy this particular complaint as a new crisis in higher education. It is not.