A Woman Not Of Her Time

Posted on March 12, 2020

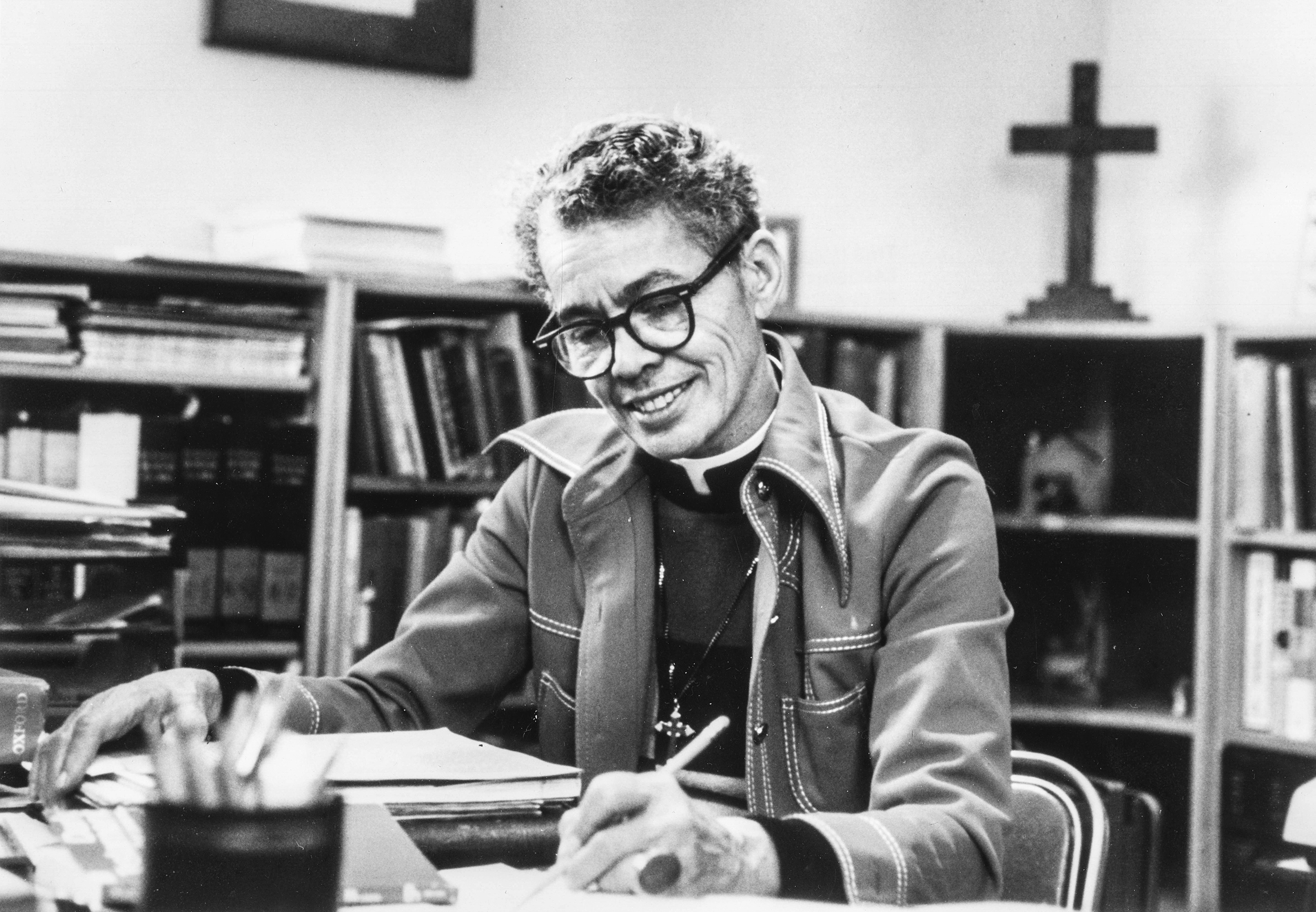

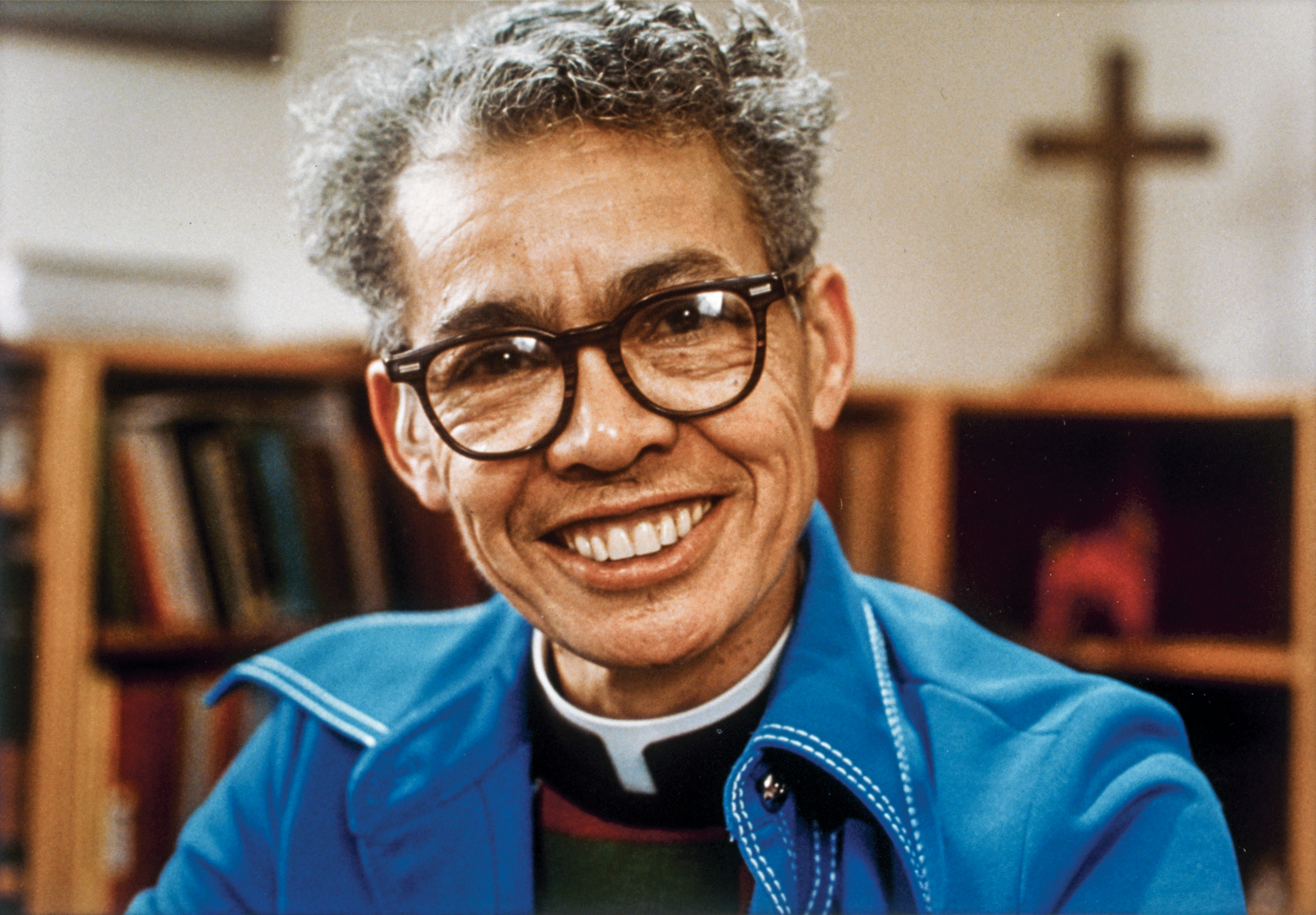

Pauli Murray. (Folder 2446: Murray, Pauli (1910-1985): Scan 1,” in the Portrait Collection #P0002, N.c. Collection, UNC)

The teenage Pauli Murray said, “No more segregation for me.” She went north and worked to end it tirelessly and prominently — and invisibly in her native North Carolina. Rejected by UNC, she had a poignant, triumphant homecoming.

By Barry Yeoman

The deep echoes of history were hardly lost on the worshippers packing the Chapel of the Cross on a Sunday morning in February 1977. Standing before them was Pauli Murray, the first African American woman ordained by the Episcopal Church in the United States. The descendant of a Chapel Hill family, she was a former civil rights lawyer whose scholarship had proven critical to the desegregation case Brown v. Board of Education. She had helped write gender equality into the law and went on to co-found the National Organization for Women.

On that day, at 66, she was a priest, celebrating her first Eucharist at the Chapel Hill church where her enslaved grandmother had been baptized. Murray cut an unassuming figure, her salt-and-pepper hair cut short and her face framed in tortoise-shell glasses. But her words soared, carrying a promise of redemption.

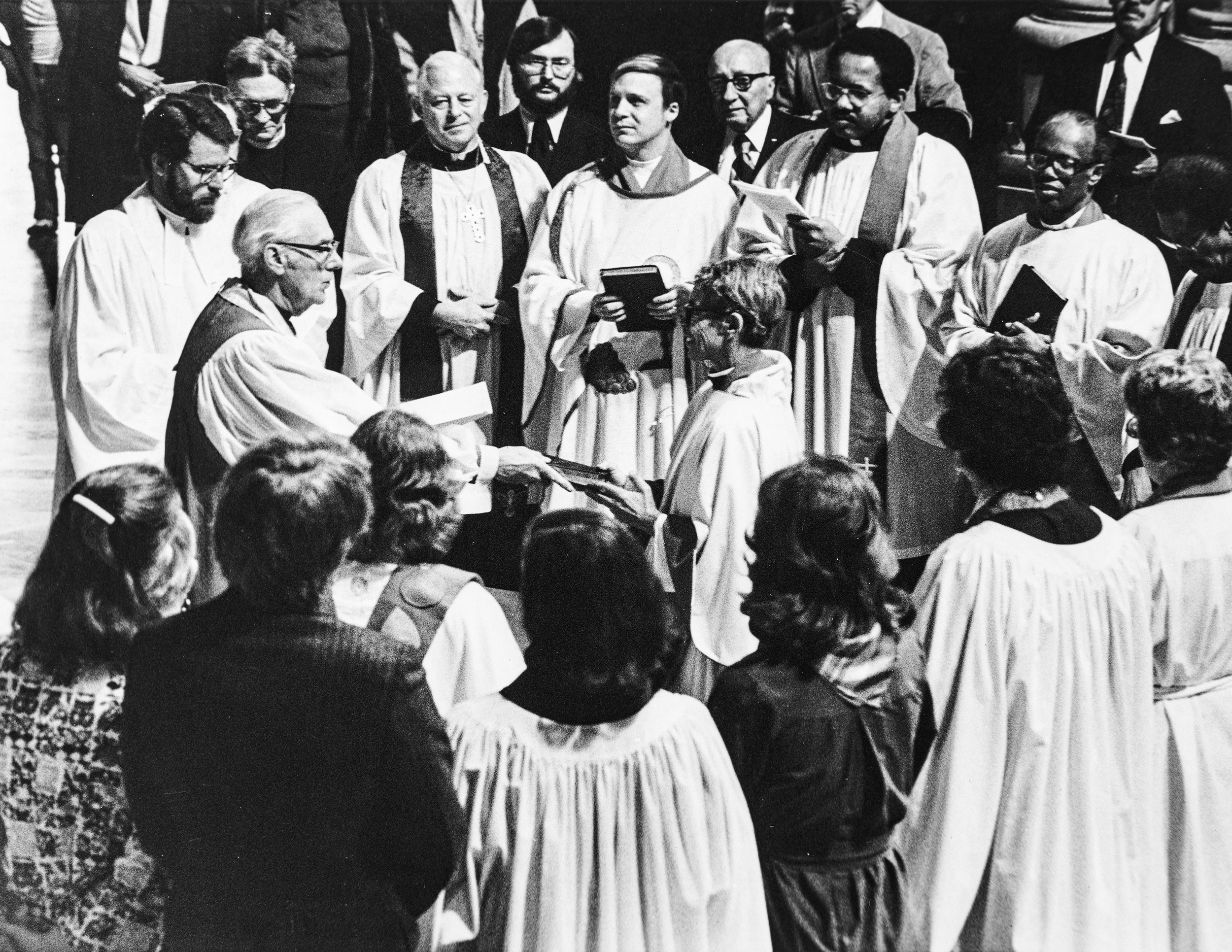

From the pulpit, Murray described a scene from the previous month. Two thousand people had filled Washington National Cathedral to watch her and two other women enter a priesthood that, until only days earlier, had been limited to men.

“The congregation could hardly contain themselves,” she said. “They did everything but speak in tongues. People embraced and wept and almost danced in the aisle.” A Washington Post reporter described the “happy chaos” that erupted during the traditional exchange of the peace. “Considering the reputation of us Episcopalians of being God’s frozen people,” Murray quipped, “it was a great victory for the thaw.”

Annual Recognition in Durham

The Annual Pauli Murray Service is held on July 1 at St. Titus’ Episcopal Church, 400 Moline St. in Durham. The date commemorates her inclusion in the Liturgical Calendar of Holy Men and Women in the Episcopal Church: sttitusdurham.dionc.org.

The Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice hosts an annual celebration in November near her birthday. This year, it is 3 to 5 p.m. on Nov. 15 at Lyon Park Community Center, 1313 Halley St., Durham: paulimurrayproject.org/becoming-involved.

This, Murray said, was a religious milestone. But it also marked “the visible beginning of the second American Revolution.” Murray imagined the reconciliation of neighbors divided by “race, or color, or religion, or sex in the gender sense, or age, or sex preference, or political and theological differences, or economic or social status.”

More personally, that day in Chapel Hill was Murray’s homecoming. In 1938, when she was 28, the University rejected her application to attend its graduate program in sociology. State law, at the time, mandated that UNC could only admit whites.

“North Carolina does not believe in social equality,” Gov. Clyde Hoey had bluntly declared. UNC President Frank Porter Graham (class of 1909) was more sympathetic, but he said his hands were tied by the Legislature and popular opinion.

“I am under very bitter attack for what little I have tried to do in behalf of Negro people,” Graham wrote to Murray. “I understand the limitations under which we must work in order to make the next possible advance.”

Rejected in her home state, detesting segregation, Murray built a life in the North as a civil rights pioneer. Her ideas influenced Thurgood Marshall, Ruth Bader Ginsberg and Eleanor Roosevelt — and today, almost 35 years after her death, they continue to pepper conversations about legal equality.

Bookending her career are two events: one rebuff and one reconciliation. Both took place in the same town. Preaching at the Chapel of the Cross, Murray made the connection clear: “A victim of The University of North Carolina’s rejection in 1938, 39 years ago, stands before you today in Chapel Hill, the site of that rejection, proclaiming the healing power of Christ’s love.”

Murray’s ordination at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 8, 1977, shortly after church leadership had voted to ordain women. (Milton Williams/Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard)

The legacy she inherited

The past few years have brought into stark relief the long reach of American slavery. The first slave ship bound for the English colonies arrived on the Virginia coast in 1619, and last year’s 400th anniversary sparked a colossal reporting project by The New York Times. North Carolinians wrestle with the meaning of a statue of a Confederate soldier that stood on Carolina’s campus. Similar reckonings have taken place over monuments from Washington, D.C., to Austin, Texas.

In this context, no historic figure seems more relevant than Pauli Murray, a North Carolinian and an Episcopal saint.

Some of Murray’s ancestral relatives were enslaved. Others were key figures in University history — local “aristocracy,” said Erik Gellman, an associate professor of history at UNC. One branch of the family owned the other, even though they all were related. “That story really matters here,” Gellman said, “because it shows generations of racial terror and the kind of sexual power that existed in the South that never was talked about.”

Murray’s great-grandmother was named Harriet Smith. She was purchased for $450 in 1834, when she was 15. In Murray’s 1956 book Proud Shoes, she described the young woman as “small and shapely, [with] richly colored skin like the warm inner bark of a white birch, delicate features, and luxuriant wavy black hair which fell below her knees.”

Bookending her career are two events: one rebuff and one reconciliation. Both took place in the same town. Preaching at the Chapel of the Cross, Murray made the connection clear: “A victim of The University of North Carolina’s rejection in 1938, 39 years ago, stands before you today in Chapel Hill, the site of that rejection, proclaiming the healing power of Christ’s love.”

Harriet Smith belonged to Mary Ruffin Smith, a white woman from a prominent family who later would become one of UNC’s benefactors. Mary Ruffin Smith bequeathed the family’s land to the University, which sold the acreage to fund student scholarships and finance the campus’s electric, water and sewer systems.

Mary Ruffin Smith’s father, and Harriet’s buyer, was James Strudwick Smith, a physician and real estate speculator who also served in Congress. He was elected a University trustee in 1821. He had two sons, both UNC alumni.

The Smiths were “a dysfunctional family, if there ever was one,” wrote historian H.G. Jones, former curator of UNC’s North Carolina Collection, in the book Miss Mary’s Money. In an incident Murray describes explicitly in Proud Shoes, one of the sons sent away Harriet Smith’s husband, then broke open the enslaved woman’s barricaded door and raped her. “Ear-splitting shrieks tore the night,” Murray wrote. “Nobody interfered, of course.”

From that assault, Murray’s grandmother Cornelia Smith was born. She was raised primarily by her white aunt Mary Ruffin Smith, while her enslaved mother “hovered anxiously in the background,” Murray wrote. At one point, Cornelia’s grandfather considered selling the girl and her mother.

At Howard Law School in the 1940s, Murray wrote a paper arguing that separate-but-equal was a losing strategy and that litigators should use the 13th and 14th amendments to argue that segregation was inherently unconstitutional. Her classmates mocked her position as radical.

Cornelia was baptized at the Chapel of the Cross in 1854 and attended services every Sunday with her aunt. Mary Ruffin Smith sat in the whites-only section downstairs. Cornelia was not allowed to join her. Instead, she and her half-sisters climbed upstairs and sat in the church’s balcony.

This was the legacy Pauli Murray inherited. Born in 1910 and raised by an aunt in Durham after her mother died of a cerebral hemorrhage, she grew up in a segregated city, hearing stories of racial violence.

“I don’t remember, for example, lynchings being prominently portrayed in the newspapers, but we would hear about them by word of mouth,” she told UNC history professor Genna Rae McNeil during a 1976 interview for the Southern Oral History Program. “My grandmother would tell me about the Ku Klux Klan riding around her little cabin up in Chapel Hill and how sometimes she’d get up at midnight and walk the 12 miles to Durham because she was afraid to stay there. This was during Reconstruction time, when apparently the Ku Klux Klan was not very happy to have a person of color owning property.”

Murray had no intention of staying in Durham. After graduating from Hillside High School, she moved to New York to attend Hunter College. “No more segregation for me,” she told McNeil. “I was what, 15? But that I knew.”

A rejection letter

In New York, Murray developed the political lens she would carry for most of her life. One of her first post-college jobs, in the 1930s, was teaching workers their rights at a division of President Franklin Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration. Working alongside an assortment of intellectuals — “young socialists, young Trotskyites, young Republicans” — Murray trained the workers to form unions, file grievances and bargain with management. She was arrested picketing the Amsterdam News, a black newspaper that had locked out its workers. And she spent six months at Brookwood Labor College in the Hudson Valley, where she studied labor economics and journalism and assisted striking automotive workers.

In that crucible, Murray came to see herself as fundamentally American: a genetic mashup of the African, European and indigenous people that defined the culture of this country.

“I love America,” she later told McNeil. “Whatever she hands me, I’m handing her back with, I hope, a championship quality. So many of my heroes, my racial heroes, have been the champions, the Jackie Robinsons, the people who climbed over and said, ‘I’ll show you.’ ”

Those were her values in 1938, when she applied to graduate school at UNC. “For Pauli, it’s a difficult moment,” said biographer Patricia Bell-Scott, professor emerita of women’s studies and human development and family science at the University of Georgia. The Depression was underway, and Murray’s job history had been spotty. An advanced degree, she reasoned, would bring more stability.

At the same time, said Bell-Scott, “she’s feeling the pressure to live up to the belief that’s part of Southern, black and her family culture”: that young women, after college, come home to care for their elders. For Murray, this meant tending to her aunt, Pauline Fitzgerald, who had earned $62 a month teaching at a segregated school and had no pension or Social Security.

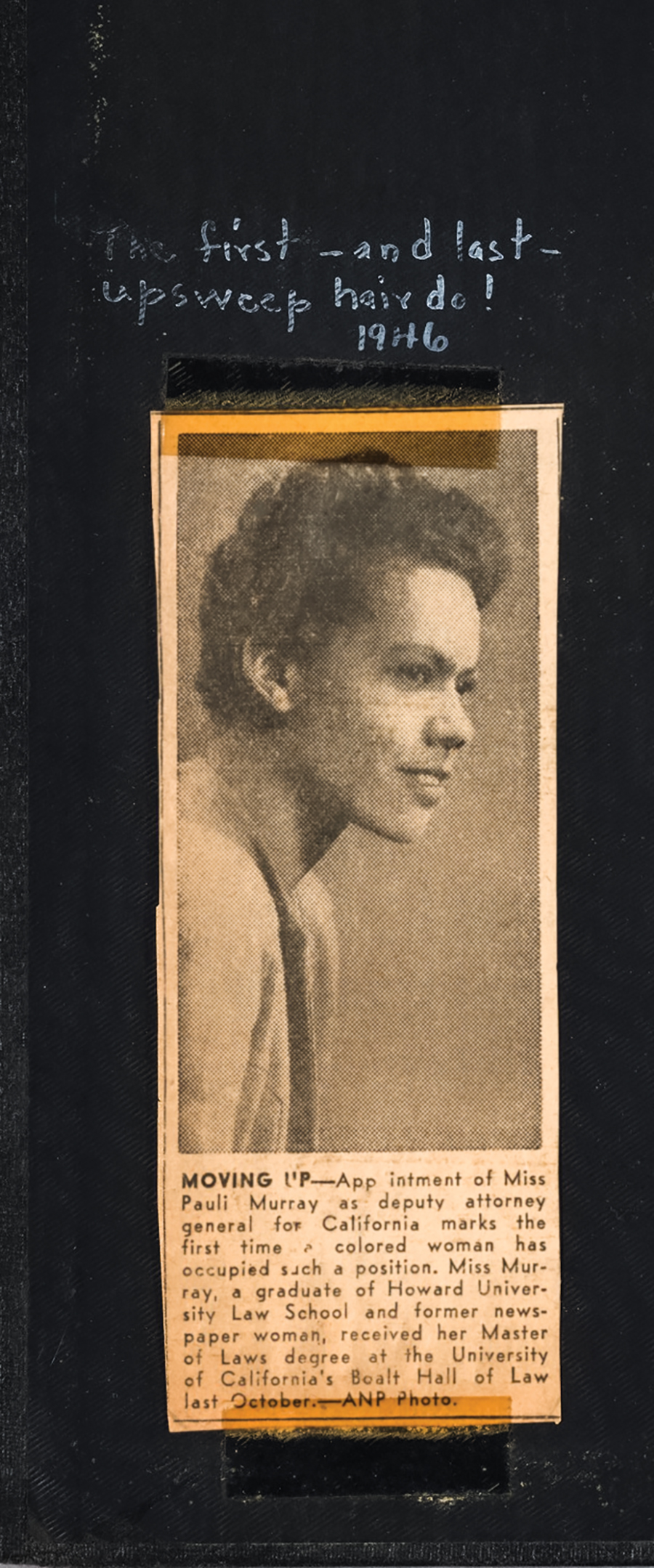

Murray as a high school graduate in 1927. She was headed for New York to attend Hunter College. In December 1938, when she was rejected for admission to a graduate program at UNC, she wrote immediately to Frank Porter Graham, who sympathized but wrote, “I am under very bitter attack for what little I have tried to do in behalf of Negro people.” (Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard)

Murray had mixed feelings. “She is petrified of the idea of returning South,” said Bell-Scott. “But if she has to, going to Chapel Hill would mean that she could stay at home, so wouldn’t have the cost of housing.”

Relatives bristled at the thought of Murray’s applying to the all-white UNC.

“They were afraid they would be lynched,” she later told McNeil. “Or that the house would burn down.” Still, Murray felt encouraged by the handful of liberal professors at Carolina. And the law was shifting in her favor: As she waited for a response, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered the University of Missouri’s law school to admit a well-qualified African American applicant.

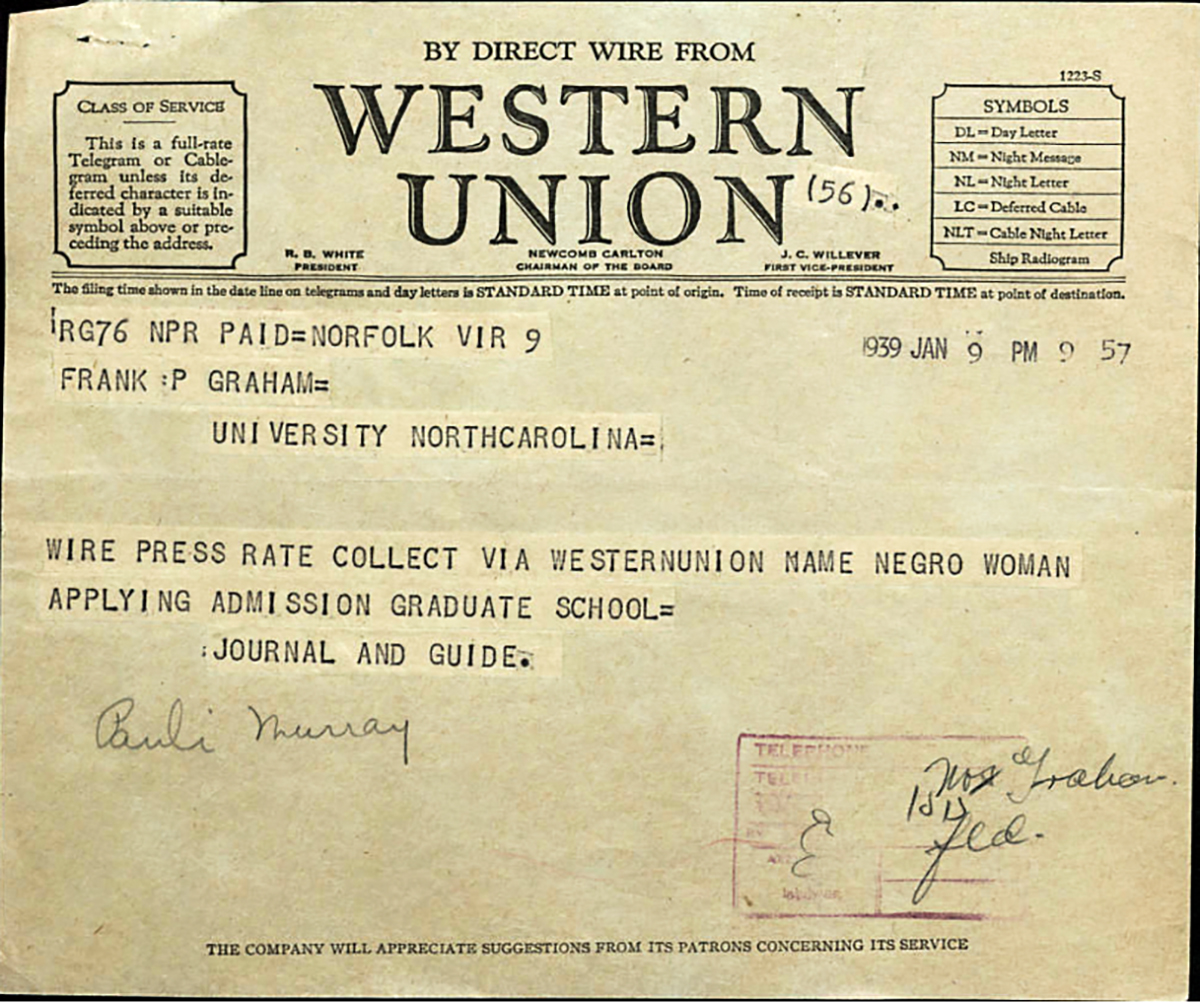

Two days after the court’s ruling, Murray received a letter informing her that, under state law, “members of your race are not admitted to the University.” Separate black graduate programs were coming to North Carolina, Dean William Pierson assured her. But he could offer no details.

By then, Murray had made the case for desegregation in a letter to President Roosevelt. He didn’t respond, but his wife did, warning that “great changes come slowly.” That exchange launched a friendship between Murray and Roosevelt, which Bell-Scott chronicled in her book The Firebrand and the First Lady.

Murray also wrote to UNC’s president after her rejection letter arrived. “How can Negroes, the economic backbone of the South for centuries, defend our institutions against the threats of Fascism and barbarism,” she asked Graham, “if we too are treated the same as the Jews of Germany?”

Graham was thinking about “fascism and barbarism” in a different way. He worried that desegregation, implemented too quickly, would incite lynching and other racist violence on the scale that North Carolina had suffered decades earlier. “The possibilities of an inter-racial throwback do not have to be emphasized in our present world,” he wrote Murray.

As the campus debated desegregation, Murray contacted the NAACP, hoping the eminent civil rights group would sue the University on her behalf, and she met with NAACP attorney Thurgood Marshall. But the organization declined to take her case, noting that Murray was not a North Carolina resident and that her political radicalism might offend a conservative judge.

This telegram appears to be a newspaper’s request for the name of the spurned student. (“Race and Ethnic Relations: Admission to Graduate and Professional Schools, Scan 60,” in the Frank Porter Graham Records 40007, Wilson Library, UNC)

Still unknown is whether Murray’s personal life also worked against her. She struggled with gender dysphoria long before there was such a word as transgender. She felt same-sex attractions and had been hospitalized for psychiatric treatment. “The NAACP’s always looking for the perfect respectable plaintiff,” Gellman said. “Murray did not fit that.

“There’s no document in the archive that’s going to have [special counsel] Charles Hamilton Houston talking to Thurgood Marshall and saying, ‘We can’t do Murray’s case. She’s queer.’ But you have to wonder.”

Winning arguments

With her UNC plans thwarted, Murray looked for another career path, eventually settling on civil rights law. “North Carolina lost a social worker,” Yale University historian Glenda Gilmore ’92 (PhD) wrote in her book Defying Dixie, “and the nation gained a social activist.”

Murray’s achievements over the next 40 years, though monumental, never received widespread recognition. Her ideas suffered from being ahead of the curve. “In not a single one of these little campaigns was I victorious,” she told McNeil in 1976. “In each case, I personally failed. But I have lived to see the thesis upon which I was operating vindicated. And what I say very often is that I’ve lived to see my lost causes found.”

At Howard Law School in the 1940s, she wrote a paper arguing that separate-but-equal was a losing strategy and that litigators should use the 13th and 14th amendments to argue that segregation was inherently unconstitutional. Her classmates mocked her position as radical. But a decade later, Marshall and his colleagues used her paper as they developed their winning arguments for Brown v. Board of Education.

“The costly lesson of American history is that human rights are indivisible,” Murray argued in her 1964 Title VII memo. “They cannot be affirmed for one social group and ignored in the case of another without tragic consequences.”

Likewise, Murray was completing a doctorate at Yale Law School when she was asked by some federal employees to write a memo arguing that job discrimination against women should be outlawed by the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which Congress was debating. Not everyone in the movement shared this view: The National Urban League insisted that African American women “should make their primary goal the lifting of the social, economic and educational status of their men.”

But Murray argued that racism and sexism were intertwined and that allowing one type of bias would hand employers a loophole. “It is exceedingly difficult for a Negro woman to determine whether she is being discriminated against because of race or sex,” she wrote.

Murray’s memo was distributed to senators and the White House. A staffer for Lady Bird Johnson, the first lady, responded and offered the administration’s support. Despite considerable pushback, Murray’s logic prevailed: The Civil Rights Act’s Title VII outlawed job discrimination on the basis of sex.

“She was intersectional long before anybody really understood what that meant,” says Lisa Crooms-Robinson, a professor at Howard Law School.

So precocious was Murray’s thinking that Ruth Bader Ginsburg, then a professor at Rutgers Law School, listed Murray as one of two honorary authors of Ginsburg’s first U.S. Supreme Court brief in 1971. In that case, a dispute between ex-spouses over their dead son’s estate, the court ruled that women were protected by the Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause. Murray had articulated that idea in the 1960s, first as a staff member for President John F. Kennedy’s Commission on the Status of Women and later as the co-author of an ACLU legal brief challenging the exclusion of blacks and women from Alabama juries.

“We put their names on [the] brief as if to say they’re too old now to be working with us, but we’re standing on her shoulders,” Ginsburg, now a U.S. Supreme Court justice, said in 2015. “We are saying the same things that they said, but now, at last, society is ready to listen.”

A loss of confidence

Murray’s legal career zigged and zagged. She ran a solo practice, worked for a large firm and held a number of government positions. She taught at a law school in Ghana. In 1968, she became a professor of law and politics at Brandeis University.

Then, in 1973, she gave up her legal career to enter the seminary.

In 1973, Murray gave up her legal career to enter the seminary. “We had reached a point where law could not give us the answers.” (Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard)

“I am not the vigorous, swashbuckling activist of my thirties,” she told McNeil, the UNC historian, two years later. “How one can use one’s energies in one’s sixties may be quite different from what one does in the thirties.”

Murray’s commitment to human rights was undiminished, she said. But she had lost confidence that her path was the right one.

“We had reached a point where law could not give us the answers,” she said. At Brandeis, she had seen up close how the debate over school desegregation and busing had riven nearby Boston. “Instead of the possibilities of reconciliation,” Murray said, “there seemed to be even greater and greater alienation.”

By then, she was thinking about mortality and preparing herself for what she called a “higher destiny.” She worried, too, about the spiritual health of the country she loved: whether its citizens, steeped in bigotry, had fallen out of harmony with their creator. “I’m not even sure that America isn’t like the Israel of the Old Testament,” she said, “that she’s not standing under the judgment of God.”

Entering the seminary in the early 1970s was a risky proposition. It wasn’t until 1976, the year Murray graduated, that the Episcopal Church’s General Convention voted to ordain women. The change took effect on New Year’s Day 1977, a week before Murray’s ordination.

The invitation to Chapel Hill for Murray’s first Eucharist came from the Rev. Peter Lee, then rector at the Chapel of the Cross. Lee had learned that Murray’s grandmother had been baptized there and that Murray had been rejected by UNC. The congregation, mostly white, had a tradition of supporting civil rights and desegregation.

“It seemed to me a no-brainer,” said Lee, who later became the Bishop of Virginia and is now retired and living in Chapel Hill. “Her presence was a sign that barriers were coming down — barriers of race, of gender, of class.”

Lee invited Charles Kuralt ’55 to film an “On the Road” segment about Murray’s homecoming for the CBS Evening News. Former Wall Street Journal editor Vermont Royster ’35, a congregant, also wrote a column. The journalists joined an overflow crowd that included UNC students hoping to witness history, and some of Murray’s relatives.

Murray preached in the morning. She returned later to offer the Eucharist. The afternoon service took place in the chapel where her grandmother Cornelia Smith had been baptized. Murray stood at a lectern donated in the memory of Mary Ruffin Smith, Cornelia’s owner and aunt. She read from Cornelia’s Bible and marked her place with purple ribbons she had saved from a box of flowers that Eleanor Roosevelt had sent in 1944, when Murray graduated Howard Law School.

Murray took her time as she administered the communion bread. She wanted to focus on, and communicate her love to, each individual. “Very often a priest may move right along the line,” she later told Kuralt. “I didn’t care. I didn’t care how long it took.”

A woman of our day

Murray died in 1985, but her ideas have continued to evolve. “The seeds that she planted, the logics that she created, the arguments that she articulated have become the basis of so many contemporary liberation movement struggles,” said Barbara Lau ’00 (MA), director of Duke University’s Pauli Murray Project and head of a nonprofit effort to restore Murray’s childhood home in Durham.

“The costly lesson of American history is that human rights are indivisible,” Murray argued in her 1964 Title VII memo. “They cannot be affirmed for one social group and ignored in the case of another without tragic consequences.” (Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard)

Take Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which Murray fought to include sex discrimination. In the years since Murray’s death, the government has expanded, if inconsistently, its interpretation of the law. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission has said that Title VII protects workers from bias based on sexuality, gender identity and sex-role conformity. So have some, but not all, federal courts. Now the U.S. Supreme Court is weighing in: In October, it heard arguments in two cases involving workers who were fired because they are gay or transgender.

Embedded in this more expansive view is something Murray wrote in her 1964 Title VII memo.

“The costly lesson of American history is that human rights are indivisible. They cannot be affirmed for one social group and ignored in the case of another without tragic consequences.”

If this view prevails, it means that Murray helped set in motion a law that, more than a half century later, will finally protect people like herself: a gender-non-conforming woman of color who loved other women. This, in a sense, is her vindication. “She wanted to create the world in which she could actually show up and not be discriminated against,” Lau said. “You can look at that as prophetic. But in some sense it was very practical. It was very much based on fighting for her own survival.”

The Supreme Court will rule on the Title VII cases this year. Regardless of the outcome, the law already has come closer to Murray’s vision of interconnected rights — the “second American Revolution” she described at the Chapel of the Cross — than it ever did when she was alive.

“Pauli Murray wasn’t a woman of her day,” says Lau. “But she is a woman of ours.”

Barry Yeoman is a freelance writer based in Durham.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.