An Unprecedented Year of Learning

Posted on May 7, 2021Amid hopeful signs that the pandemic’s grip is loosening, UNC alumni who work as N.C. educators look behind them, seeing the damage done, and ahead to a daunting catch-up.

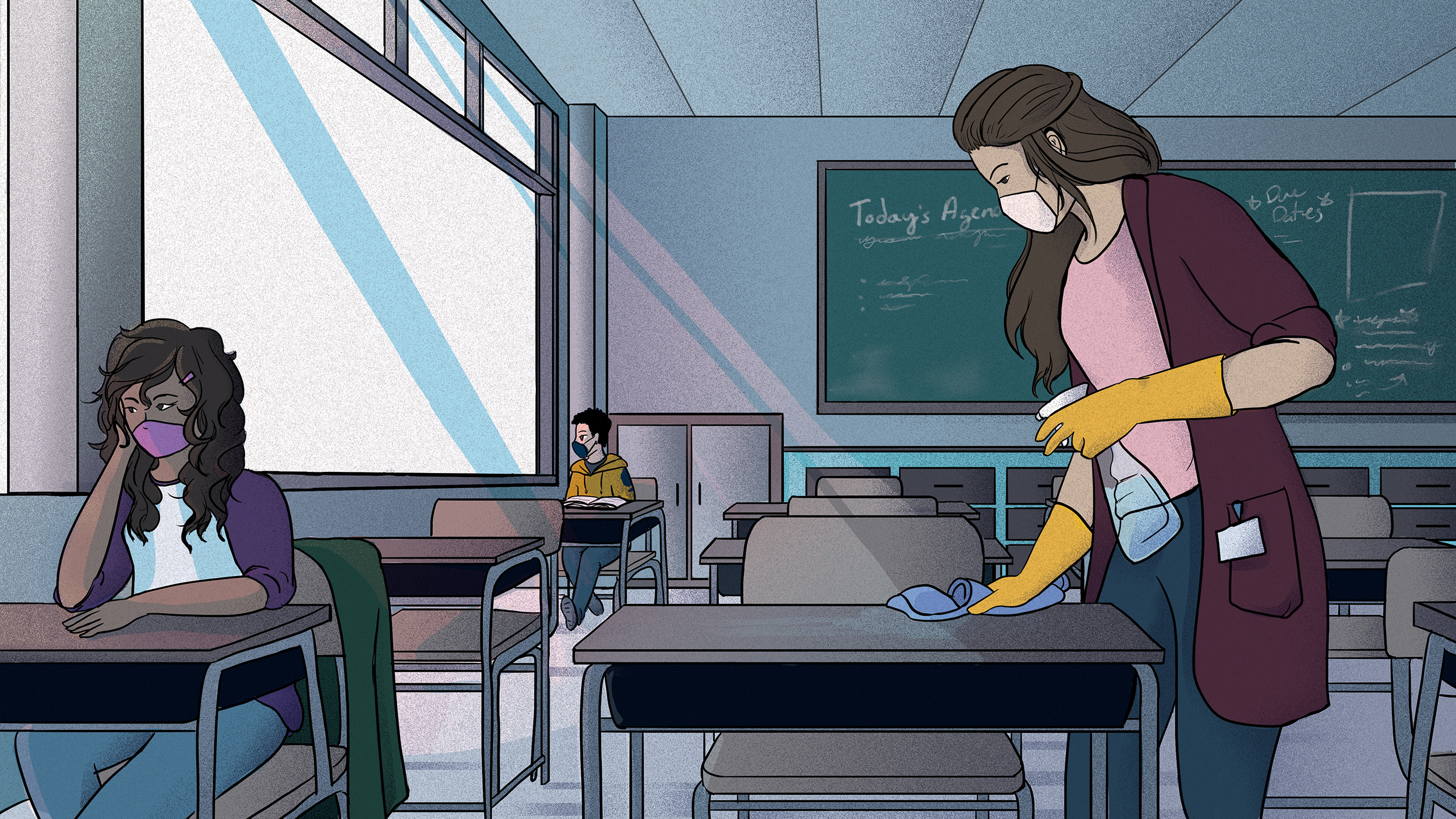

by Eric Johnson ’08 | illustrations by Haley Hodges ’19

When Cathy Moore’97 (MSA) answered her cellphone on a Thursday afternoon in late February, you could hear a chiming school bell and a garbled intercom announcement in the background. “Sorry,” said the superintendent of the Wake County Public School System, the state’s largest district. “I’m in a school right now — my fifth school visit so far today.”

It was the first time in nearly a year that most Wake County students were back in classrooms, and Moore was making the rounds to see how things were going. “I want to see if our safety protocols are working, to hear if people have questions,” she said. “I’m trying to get to as many schools as I can.”

She also was handing out awards. The district recognizes a first-year Teacher of the Year in each school category — elementary, middle, high and special education. Moore wanted to congratulate the rookie educators in person. There are now teachers across the state who started their careers behind a computer screen, navigating their first semester on the job without ever meeting students in person. Months later, those educators were getting into the classroom for the first time, standing in front of masked-up, carefully distanced students.

The past year saw the largest disruption to schooling in American history, and teachers, administrators and policymakers are deeply worried about how much learning students have really done.

“I think all of our teachers have done a tremendous job navigating this new virtual learning and teaching environment, but it’s not the same as being in the classroom,” Moore said. “I think we have a long ways to go in assessing the impact of the year gone by.”

That impact is likely to be enormous. The past year saw the largest disruption to schooling in American history, and teachers, administrators and policymakers are deeply worried about how much learning students have really done. “When August comes, it will have been 18 months since many middle and high school students will have had daily, in-person school,” said Pam Hartley ’93, the former CEO of Communities in Schools of North Carolina and now director of district partnerships for N.C. Education Corps. “When you actually add all of that together and think about what it means for students academically and socially … it’ll just put a hitch in your throat.”

“We need more of a bridge between home and school. You can’t put all the work of recovery on schools, and you can’t put all the work on parents. It has to be a shared burden. Parents have been proxy educators for a year now. Things can’t just go back to the way they were before.”

“We need more of a bridge between home and school. You can’t put all the work of recovery on schools, and you can’t put all the work on parents. It has to be a shared burden. Parents have been proxy educators for a year now. Things can’t just go back to the way they were before.”

— Cassandra Davis ’09 (MA, ’13 PhD),

associate professor of public policy, UNC

It also puts a hitch in any notion that schools can simply pick up where they left off in March 2020. That’s when millions of students from kindergarten to college were displaced from their classrooms, sent home to protect against the spread of the coronavirus. What began as a temporary emergency measure stretched to weeks, then months and ultimately for a full academic year in much of the country. Teachers, parents and district leaders were left scrambling to figure out online learning, and most of them were starting from scratch.

There are more than 56 million K-12 students in the U.S., and only about 20 percent of the schools they attend offered any online classes prior to the pandemic. Fewer than a million students, by one estimate, went to school entirely online. All of that made for a steep learning curve when school buildings went dark.

“What I’ve seen across the state is just astonishing,” Hartley said. “We’ve got these huge institutions that were able to flip to virtual work and virtual learning so quickly, to roll out and purchase thousands of computers and [Wi-Fi] hotspots so quickly — it’s just been remarkable.” But it also means schools have been in triage mode for most of the past year, trying to do the best they can with everything from remote teaching to mobile meal distribution. There’s been little time to plan for what happens next. “We’re still very much in emergency mode,” Hartley said. “When do you start to transition to recovery, to look forward and anticipate where our students are going to be in the fall?”

An informal email survey last fall by the Carolina Alumni Review found that alumni working as K-12 teachers have had wildly different experiences since the beginning of the pandemic. Some reported strong engagement from their students during months of online learning; others are concerned about the academic and emotional toll that prolonged school closures have inflicted.

“It is an extremely tough time, and everyone involved is being given entirely too many responsibilities for what is reasonable,” wrote Grace Rust ’17, a French language teacher at Eastern Alamance High School. “Students do not have access to the same resources, internet bandwidth or learning environments as their peers. It is extremely hard and trying for them, too.”

“Some of our ways of measuring student success have to change now. We can’t compare everyone exactly the same way. … I think it is important we know where youngsters are now, because that’s the only way to know what we need going forward.”

“Some of our ways of measuring student success have to change now. We can’t compare everyone exactly the same way. … I think it is important we know where youngsters are now, because that’s the only way to know what we need going forward.”

— Alisa McLean ’09 (EdD),

superintendent, Granville County schools

In Wake County, high school math teacher Vanessa Wilkes ’99 (’00 MAT) wrote about the challenge of building relationships with her students over video chats. She’s also concerned about divergent paths her students are taking without the shared environment of a classroom. “Some of my students seem to prefer remote learning. They stick to a schedule, work well independently and have learned to advocate for themselves,” Wilkes wrote. “Other students abhor remote learning and seem to even be rebelling against it. They might attend Google meets for class daily but are failing because they won’t complete and submit assignments. Most students fall somewhere between these two extremes.”

Assessing the need

Even before the pandemic, there were sharp performance gaps among students that tracked closely with parental income and education level. Teachers and school officials fear that those gaps will widen after a year when some parents were able to provide close supervision of at-home learning while others simply couldn’t. The huge variance in student experiences during the pandemic will create equally huge challenges for teachers in years to come.

N.C. State Superintendent Catherine Truitt warned lawmakers in March that nearly a quarter of students statewide were “at risk of academic failure” after a year of disrupted learning. A December study from the consulting firm McKinsey & Co. warned that American students will have lost, on average, the equivalent of five to nine months of learning by the end of the spring 2021 semester. Low-income and minority students are projected to have even worse outcomes, given often lower levels of support for at-home learning. And learning loss compounds over time. Kids who don’t master algebra I this year aren’t going to excel in algebra II next year, and they almost certainly will struggle to reach college-level math. “Much damage has already been done, and even the best-case scenarios have students half a grade level behind in June,” McKinsey researchers wrote. “To catch up, many students will need step-up opportunities to accelerate their learning. Now is the time for school systems to prepare post-pandemic strategies that help students to meet their full potential.”

In most districts, those catch-up strategies are just beginning to take shape. Administrators and teachers have been so focused on salvaging the past academic year that they’ve had little time to think about what comes next. “Schools are really just trying to survive,” said Eric Houck ’92, an associate professor at UNC’s School of Education who studies school policy and finance. “They’ve been really left to their own devices. You have 115 separate districts in North Carolina trying to solve the exact same problems in separate ways.”

“We’re not opposed to giving tests to get information on students’ progress or determine how far behind they are or anything like that. What we don’t want is the negative consequences that are tied to it. We need diagnostic testing right now, not accountability testing.”

“We’re not opposed to giving tests to get information on students’ progress or determine how far behind they are or anything like that. What we don’t want is the negative consequences that are tied to it. We need diagnostic testing right now, not accountability testing.”

— Patrick Miller ’93, superintendent, Greene County schools

Just as there’s been no consistency in how schools have handled the pandemic, there’s little agreement about what should be done after students fully return to the classroom. State lawmakers are pushing for at least 150 hours of summer school instruction to help struggling students, but the legislation leaves key details up to district leaders.

“For those kids who are at risk and suffered a lot of learning loss, the summer would just be the start,” said Patrick Miller ’93, superintendent of Greene County schools and president of the N.C. School Superintendents Association for 2020–21. “We also want to create a robust after-school program with tutorials in reading, math and science. That ought to get us a good ways down the road of recovering what these kids have lost.”

Those extra school hours will be voluntary, but Miller hopes that a lot of families will embrace the opportunity. “I’m sure a lot of our parents will see it as free day care,” he said. “I don’t care how they see it as long as they send the kids.”

Miller also is thinking about what kind of testing will be needed to help teachers assess student needs. North Carolina, like most states, suspended end-of-grade testing last year because of the pandemic. And even if end-of-grade testing were to happen this year, it won’t give teachers the kind of detailed insight they need to improve student learning, Miller said.

“We’re not opposed to giving tests to get information on students’ progress or determine how far behind they are or anything like that,” Miller said. “What we don’t want is the negative consequences that are tied to it. We need diagnostic testing right now, not accountability testing.” Miller doesn’t want to see schools or teachers labeled.

That sentiment was echoed by Alisa McLean ’09 (EdD), superintendent of Granville County schools. “Some of our ways of measuring student success have to change now,” she argued. “We can’t compare everyone exactly the same way, because the experiences have been so different. I think it is important we know where youngsters are now, because that’s the only way to know what we need going forward.”

Frayed ties

Superintendent Moore, in Wake County, also is worried about the tension that emerged over the past year between parents eager for a return to in-person learning and teachers who were reluctant to come back to the classroom before widespread vaccination. Like many of the larger districts across the country, Wake repeatedly delayed reopening plans in the face of resurgent coronavirus cases and stiff resistance from many teachers who saw in-person learning as an unnecessary risk.

“Schools are really just trying to survive. They’ve been really left to their own devices. You have 115 separate districts in North Carolina trying to solve the exact same problems in separate ways.”

“Schools are really just trying to survive. They’ve been really left to their own devices. You have 115 separate districts in North Carolina trying to solve the exact same problems in separate ways.”

— Eric Houck ’92, associate professor,

UNC School of Education

That left district officials like Moore caught between genuine empathy for staff and increasing parent pressure to resume classroom learning. By the time the Wake County school board voted in February to return the majority of students to the classroom, surveys showed more than 90 percent of parents were comfortable with some level of in-person learning.

“We have to deal with the reality that we’ve had a widening disconnect between our school-based staff, who have concerns about returning to the building and having in-person instruction, and our parents, who are very interested in returning to classes,” Moore said in late February. “We have some work to do to repair that relationship.”

For some families, it’s already too late. Public school enrollment fell across the state during the pandemic even as charter schools and private schools — which were more likely to maintain in-person learning — continued to grow. “Parents who want their kids to be in school might’ve found charter options that were still operating in person, and there’s a good chance they won’t move their kids back to the public system,” said Houck, the School of Education researcher. “If parents take their kids out of the public system and find an acceptable alternative, we’re not sure they’ll be super excited to make another disruptive transition with their kids.”

Even in smaller school districts, where teachers generally have felt more comfortable being back in class, school leaders had to cope with divided public opinion about the right time to bring the kids back in person. In Greene County, Superintendent Miller had his staff conduct a phone survey of parents before the fall semester started. He found the district’s families almost evenly split on whether they preferred fully remote learning or an in-person option, so he and his staff came up with a plan to offer both options.

“We had some really challenging meetings with the principals, talking about logistics and how we were going to make this work,” Miller said. “Looking back, I’m amazed we got it done.” The hybrid approach meant that teachers had to pull double duty through most of the school year, handling in-person instruction for one group of students and remote teaching for another cohort. Given the uncertainty and anxiety about the virus, Miller didn’t think it was right to force either group of parents to compromise, even if that meant more work for his employees.

“My job is to serve the children of this community,” Miller said. “This is what they indicated they wanted, so it was up to me and my staff, my team, to figure out how to deliver it. That’s the mindset we took, and we’ve been lucky and been able to pull it off.”

“I think all of our teachers have done a tremendous job navigating this new virtual learning and teaching environment, but it’s not the same as being in the classroom. I think we have a long ways to go in assessing the impact of the year gone by.”

“I think all of our teachers have done a tremendous job navigating this new virtual learning and teaching environment, but it’s not the same as being in the classroom. I think we have a long ways to go in assessing the impact of the year gone by.”

— Cathy Moore ’97 (MSA), superintendent,

Wake County Public School System

The sharp division of opinion about when and how to get back to the classroom has been evident in the guidance from state leaders. For most of the 2020–21 school year, Gov. Roy Cooper ’79 (’82 JD) left it up to local school districts to decide when they were comfortable getting students back in school buildings. That meant some districts, largely in the rural parts of North Carolina, spent most of the past year with at least some in-person learning, while larger districts in Wake, Charlotte-Mecklenburg, Guilford and elsewhere spent much of the year fully remote.

Multiple studies by political scientists found that district-level reopening plans across the country were correlated more closely with political leanings than public health data, with left-leaning communities more likely to opt for remote learning and conservative counties more likely to bring students back to the classroom. In North Carolina, the Republican-led Legislature pushed for districts to fully reopen while Cooper and the N.C. Association of Educators urged caution. After protracted negotiations and veto threats, the governor and state lawmakers reached an agreement in March requiring all schools to offer in-person learning, though families could still opt for online-only classes. “When this pandemic seized our state a year ago, one of the hardest decisions we made was to close our schools to children and to put them in remote learning,” Cooper said in announcing the compromise. “Even though it saved lives and was the right thing to do, it hurt.”

The divide over school reopening left local officials in a bind. “Rather than a common national response to the pandemic, leadership devolved to governors, mayors and school boards to devise their own policies,” wrote Ferrel Guillory, now retired from UNC’s journalism faculty, in an October column for the website EdNC. “The upshot … is a state with an educational patchwork quilt.”

It remains to be seen how the mix of admiration and frustration toward schools will affect long-range support for public education. Millions of parents have experienced how hard it is to keep students learning all day, and there’s a renewed appreciation for the role that schools play in students’ happiness and social connection. But a year of public wrangling about reopening has taken a toll.

McLean, the Granville County superintendent, saw her board repeatedly vote for a return to in-person learning only to retreat as virus numbers trended back up. The district opened fully remote last fall, gradually brought some students back into schools, then went back to remote learning in December as coronavirus cases spiked across the state. “Our heart’s desire is to have children return to school as soon as possible,” McLean told The Daily Dispatch of Henderson in January, after the school board voted for another delay in reopening. “Unfortunately, the indicators are simply going in the wrong direction.”

By the end of February, with most of her teachers and staff set to receive vaccinations, McLean was once again eager to get students back in school. The scramble to keep students fed, connected and engaged in a sprawling rural district had taken a toll. “This has been one of the most challenging years I’ve ever seen,” said McLean, who has worked in four school districts and helped train hundreds of principals across North Carolina. “Everyone is continuing to push themselves, and I’m amazed at what we’ve been able to accomplish for our babies. But I have days when I go home and just fall across the bed — I’m just done. There’s nothing else left.”

Now: All hands on deck

That sense of exhaustion among teachers and administrators is yet another source of worry for policymakers. If school districts are going to run intensive summer makeup programs as well as consider extending school days and add more tutoring to help students make up for lost time, they’re going to need help.

“We’re still very much in emergency mode. When do you start to transition to recovery, to look forward and anticipate where our students are going to be in the fall?”

“We’re still very much in emergency mode. When do you start to transition to recovery, to look forward and anticipate where our students are going to be in the fall?”

— Pam Hartley ’93, director of district

partnerships for N.C. Education Corps

The program Hartley joined, N.C. Education Corps, is a new initiative from the state board of education and the governor’s office to fund tutors and part-time support staff in schools across the state. “Our schools need help, and we need more people to do it,” Hartley said. “So how can we call up North Carolinians to get involved? How do we connect them?” The Education Corps has been recruiting recent college graduates, retirees and people working reduced hours because of the pandemic and matching them up to school districts that can use the help. “The overwhelming need of our districts is tutors and mentors,” Hartley said. “It’s as much about social-emotional support — just connecting with students and keeping them motivated — as it is about academics.”

Cassandra Davis ’09 (MA, ’13 PhD) is an associate professor of public policy at Carolina, and she has studied the way eastern North Carolina schools have coped with prolonged disruption after major hurricanes. The aftermath of the pandemic, she said, will demand a new level of engagement between schools and parents.

“We need more of a bridge between home and school,” Davis said. “You can’t put all the work of recovery on schools, and you can’t put all the work on parents. It has to be a shared burden. Parents have been proxy educators for a year now. Things can’t just go back to the way they were before.”

It remains to be seen how the mix of admiration and frustration toward schools will affect long-range support for public education. Millions of parents have experienced how hard it is to keep students learning all day, and there’s a renewed appreciation for the role that schools play in students’ happiness and social connection. But a year of public wrangling about reopening has taken a toll.

“Parents and community members who were supportive and helpful back in March and April were by now tired of having their kids home all the time, and the wearing of masks and other safety protocols had been so politicized that the job began to feel like going into battle every day,” wrote Elizabeth Boulter ’90, a music teacher in Yancey County, responding to the Review’s fall survey. For her, the shared hardship of the pandemic didn’t seem to translate into solidarity with schools. “I am sorry to be discouraging, but after 30 years and two months of teaching, this is the most discouraged I have ever felt.”

No matter how you see the year gone by, there is a lot of rebuilding ahead.

Eric Johnson ’08 is a writer in Chapel Hill. He works for the College Board.

Mixed Reviews

The Review asked alumni who work in K-12 education around the world how teaching during the pandemic has been going for them. Here are excerpts of some of their responses.

• Jamie Hickman Wilson ’01 (’02 MAT), Watauga High School: This fall, I definitely struggled to develop a rapport with my students through a screen. Good teaching and learning happen most easily when there is a sense of classroom community, and that has taken much longer to develop this year. However, I am really proud of the resilience and flexibility that my students have developed. • Joseph Eugene Hollowell Jr. ’03, South Granville High School: Blessed are the flexible, for they shall not break. • Emma Leigh Kiger Couch ’99, Reagan High School: I had some students that checked out. I never heard from them again for the entire semester. And there was no penalty. I was absolutely craving student contact. And they were, too. • Amanda Radford ’15, Wendell Creative Arts and Science Magnet Elementary: I quickly learned that these kids are adaptable, and they find ways to solve technology issues even when I don’t know them. We’ve learned keyboard shortcuts together, become screen-splitting pros and so much more. If they are this amazingly tech savvy now as third graders, I can’t wait to see the things they’ll do as they get older. • John Marshall Lancaster ’90, Catholic High School, Laurel, Md.: Virtual instruction offered less discipline of the students, but given that students were at home, they were often more focused with fewer distractions. I am not convinced that the virtual experience grows connections like the on-site experience does. I miss the students. • Jillian Harper ’07 (MAT, ’10 MSLS), Walter M. Williams High School, Burlington: Originally I was overwhelmed and frustrated because I am not able to give my students the same experience with hands-on service learning in our library. [But] I’ve gotten excited because this has become something I will be able to use with students in the future, whatever remote/hybrid/in-person schedule we have. • Lori Hughes Mottesheard ’83, Meadowlark Elementary, Winston-Salem: I have returned to teaching basic key concepts through direct 30-minute instruction. And best of all, through our Zoom meetings, I feel that I know each individual student in a more direct way. • Stephen Guy Fullam ’88, Vidalia High School, Vidalia, Ga.: Our biggest problem is that the virtual students for the most part are not doing their work at the rate they should be. Many of them are way behind. There is no doubt that in-person learning is far superior for high school students. Most high school students, in general, are not mature enough and responsible enough to do this work on their own. • Meghann Mohler McMahon ’00, Bryn Mawr School, Baltimore: When we went remote in the spring, my main job was to give my kindergartners a sense that they were safe and cared for. In the blink of an eye, their entire world shifted and changed. As I went from hugging them in moments of joy and wiping their tears when they fell on the playground, to trying to connect with them through a computer screen, I discovered that [they] just needed some consistency — and that consistency was me. Fast-forward to the fall, and I am currently teaching in person. The kindergarten of 2020 looks very different than years past; there is no more collaborative play, and they are separated by plexiglass. However, what these 5-year-olds have learned and exhibited is resilience! I am incredibly proud of how these little ones have mastered how to think, learn and feel in the times of this pandemic. We all could take a lesson from them. • Thomson Lipscomb II ’98, Khon Kaen Vithes Suksa Bilingual School, Thailand: I can’t describe how lucky I feel to be here [in Thailand, where COVID-19 cases have been relatively low]. We try to practice physical distancing, but it’s an incredible challenge. Students forget to put their masks on. Students just don’t feel like wearing a mask. I tell my students that we are practicing protecting ourselves so that we will be accustomed to these measures when the virus finds its way into our lives. They’re fourth graders. They believe me, for the moment, but when the threat isn’t right in front of them, they get distracted. They just want to play. I get it. Sometimes I take my mask off, too. My heart goes out to my American family, friends and colleagues. It will get better. • Jennifer Paige Buckner ’95, New Hope Middle School, Dalton, Ga.: I think the biggest takeaway I have had since March 2020 is that our students need to be face-to-face. Our kids needed each other, and we needed them. I saw such a difference in our students after we had been back face-to-face for about a month. They smiled bigger, and they laughed a little louder. I realized I needed them in the building as much as they needed to be there. • Mark C. Carson ’00, North Pitt High School, Bethel: It has always been relatively easy to get to know the students that are in front of you. However, during this time, it is even more important to establish relationships with students who are learning virtually. • Richard Smith Dixon Jr. ’01 (PhD), Episcopal High School (retired June 2020) and Averett University, Danville, Va.: A motivated student is motivated no matter what; an unmotivated student, in a virtual setting, will drift off into the nether world of internet space, often never to be heard of again. • Karen Jones Dickerson ’86, Wilton Elementary School, Franklinton: The best thing that I have witnessed in this situation is the willingness of students to help each other. Someone may be having technical issues, and the children will say try this or do that. They will encourage each other. It renews my faith in humanity. • Susan Hewett ’90, International School of Latvia, Riga, Latvia: Kids are more disengaged than ever. I feel as if I am working harder to teach remotely than I did in the classroom. Sometimes, I am drowning. • Sarah Hubert ’11, Christ Church Episcopal School, Simpsonville, S.C.: Teaching in person this fall has been challenging and stressful, to be sure, but all the more rewarding to be together with students in the classroom. Students, teachers and parents all seem to have a renewed sense of appreciation and gratitude for school as an institution. • Grace Rust (Olivia Grace Naeger) ’17, Eastern Alamance High School, Mebane: Society finds it easy to be hard on teachers and be unappreciative, and we are now teaching into their living rooms and are on full display. We are vulnerable, we are tired, and we are trying our hardest, as we always have. Students are acting as caregivers, cafeteria workers and teachers to their younger siblings as they themselves try to learn and work simultaneously. It is extremely hard and trying for them, too. • Bobby Lee Padgett II ’88, Highland School of Technology, Gastonia: I am still dealing with students who have issues of equality of access to the internet even in a large suburban county like Gaston. Reasons include poverty and/or living in the rural enclaves in the county with poor service. I can only imagine what some of the poorest, most rural counties in the state are dealing with. • Lisa Hendrick Mitchell ’88 (’89 MAT), Overton High School, Memphis: Very quickly it became obvious that there were not enough hours in the day. Teachers were feeling stressed, frustrated and couldn’t see how this level of work (especially outside of the school day) could be sustainable. • Stacy Collins Lynch ’83, Charlotte Country Day School: Children are resilient! Since August, I have taught 12 children in a classroom in a large gym with four other colleagues. The students and I feel so fortunate to be attending school in person. We have formed a very strong sense of community even with the social distancing and masks. • Elizabeth C. Boulter ’90, Yancey County schools: During August and September, our community, like so many others throughout the country, became very divided, and the schools and teachers became pawns in the struggle for power. Parents and community members who were supportive and helpful back in March and April were by now tired of having their kids at home all the time, and the wearing of masks and other safety protocols had been so politicized that the job began to feel like going into battle every day. In my hometown, where I have always felt respected as a teacher, I now heard voices saying that we were just lazy and didn’t want to do our jobs. • Dennis Joseph Moore ’92, Milton Hershey School, Hershey, Pa.: Students are in a mental health crisis in terms of anxiety, depression and simply boredom. This is simply not a normal year, and students can’t be expected to retain or learn as they normally do. A stressed brain simply cannot learn as well as a safe one, and all of our students have very stressed brains. I do see students being kinder to each other. They can relate to each other with fewer obvious differences. There are no sports stars or standouts in anything right now. They are all in the same boat and not in charge of the direction it is headed or who is steering it. • Sarah Miles Featherer ’97, Granby High School, Norfolk, Va.: When people ask me about how virtual teaching is going, I usually say, “It’s all of the work and none of the fun.” If this pandemic has taught me anything about me as an educator, it’s that the students are the reason I love my job. I miss them. I miss me with them. I miss the teacher I was in the classroom. Unfortunately, the students that were difficult to reach in the classroom are exponentially more difficult to reach virtually. • Erica Pressley Schwartz ’11, Pascack Hills High School, Montvale, N.J.: Teaching during the pandemic has allowed me to practice some of the basics: being extremely clear with directions, not assuming that students understand or can see what I have put up, and above all being patient as students navigate new ways of doing school as well as dealing with technology issues. • Sharon H. Baker ’76, Rochelle Middle School, Kinston: Being of a particular age, I found learning the technology process the most difficult. I had a moment when I realized with student learning, some may struggle more than others, but with practice everyone can be successful. • Carrie Stockard ’83, St. Pius X Catholic High School, Atlanta: I don’t know whether academics can truly thrive in this environment. I think our outcomes are just going to be behind where they normally are for a couple of years. But if we can remember in the midst of our fear and frustration that the kids are struggling as much as we are, we can all come out of this alive and having learned a lot.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.