Confronting Our Saunderses: Carolina and Disparate Visions of the Future

Posted on Jan. 13, 2017There is something new to see on the campus. Two things, really — history lessons in white and black. A year and a half after a spring punctuated with the protests that students of color were not whole students of Carolina and the demand that everybody else face up to it, the University has set out in words and pictures an accounting of the regrettable events and turbulent politics that defined race relations in North Carolina in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

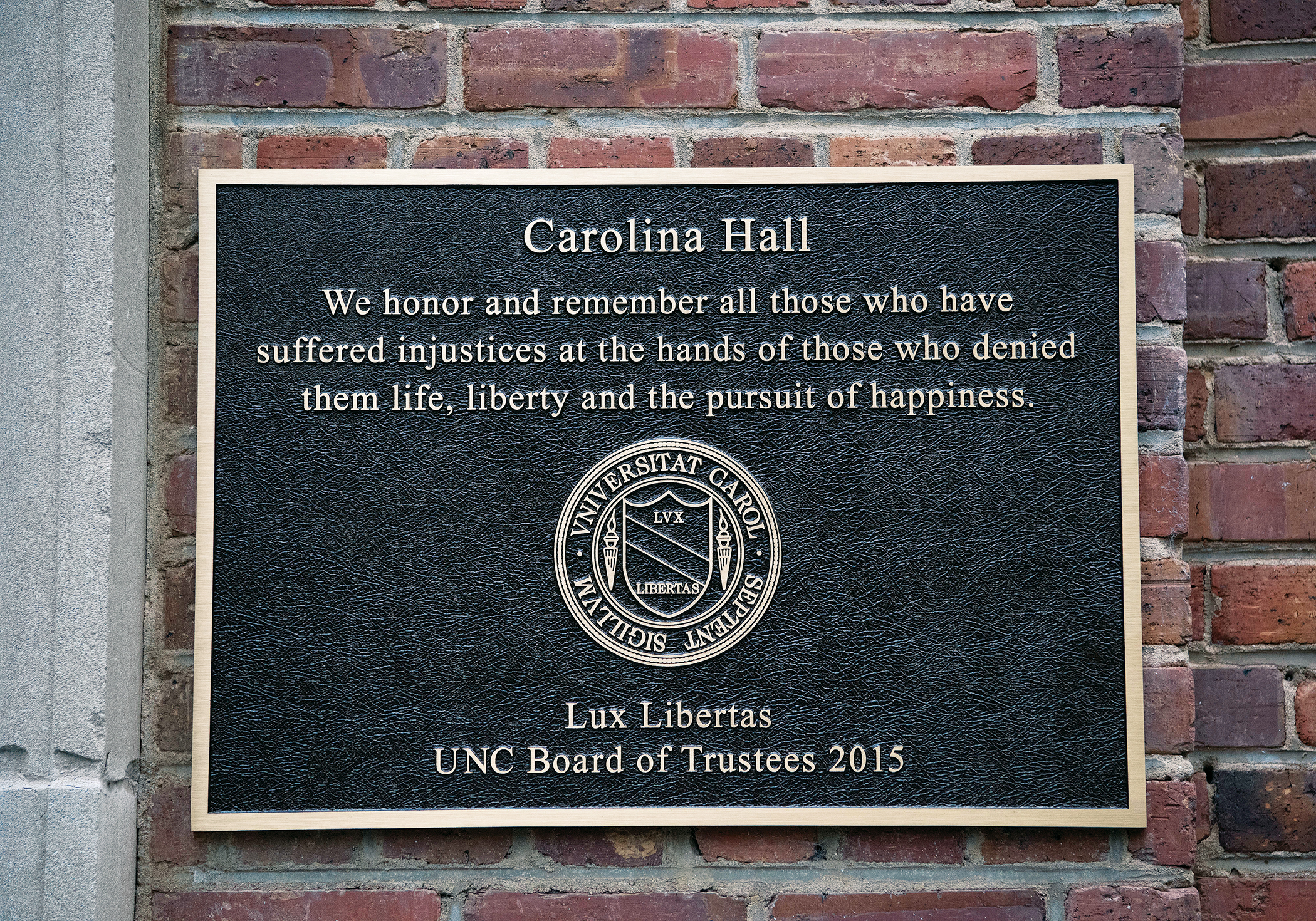

This plaque is on the building’s exterior by the front door. (Photo by Jon Gardiner ’98/UNC)

The setting is Carolina Hall, nee Saunders, after the Civil War soldier, historian and statesman. Some still doubt William Saunders (class of 1854) really was the state’s leader of the Ku Klux Klan, but there is no question that the UNC trustees cited that line on his resume when they conferred the honor in 1922. That, the trustees of 2015 said, justified an unprecedented removal of his name, replaced with the generic.

As part of a promise from South Building to the students to publicly confront the University’s racial history, a seven-panel exhibit opened in the Carolina Hall front lobby in mid-November.

The exhibit covers one wall and part of another in the Carolina Hall lobby. Other exhibits covering the University’s racial history are planned for McCorkle Place. (Photos by Jon Gardiner ’98/UNC)

It takes up where the war over the subjugation of African-Americans ends, which set off a long period of turmoil, as an alliance of blacks, American Indians and some whites battled in the name of Fusionism for inclusiveness against white supremacists. By 1868, a victorious Republican Party rode in on a mandate for a statewide public school system and a new constitutional right of every man to vote.

It takes up where the war over the subjugation of African-Americans ends, which set off a long period of turmoil, as an alliance of blacks, American Indians and some whites battled in the name of Fusionism for inclusiveness against white supremacists. By 1868, a victorious Republican Party rode in on a mandate for a statewide public school system and a new constitutional right of every man to vote.

Supremacists organized around the Democratic Party answered with terror in the form of Klan violence, voting fraud and a coup d’etat in Wilmington in 1898.

The story is told from the points of view of segregationists and those, including black leaders, who defied them. One of the former, Gov. Charles Brantley Aycock (class of 1880) — who may have escaped Saunders’ fate when the trustees imposed a moratorium on further name changes — gets his due as a champion of schooling but an avowed campaigner for the disenfranchisement of blacks. (Aycock’s name is on a UNC dorm; other universities have removed his name from their buildings.)

The exhibit traces the beginnings of the Jim Crow era of institutionalized racial segregation, then jumps ahead to the state’s official mea culpa for slavery in 2007 and the efforts of modern-day students to shine lights on the events.

The last panel is laid over a photo of men removing the name Saunders Hall. It includes a nod to the students’ unsuccessful effort to have the building renamed for author and civil rights activist Zora Neale Hurston, who secretly attended a class at Carolina in 1940, long before blacks were allowed admission.

The task force that created the exhibit will turn its attention to concepts for public displays in McCorkle Place, where the Confederate statue Silent Sam stands guard nearby the Unsung Founders memorial; the latter is controversial for seemingly minimizing the people and the effort it was designed to recognize. The University also is working on an inventory of buildings and monuments on the campus that have racial significance and on an online student orientation program on racial history.

— David E. Brown ’75

The entire exhibit in the Carolina Hall lobby can be viewed online at carolinahallstory.unc.edu.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.