Great Adaptations

Posted on Sept. 24, 2021

Luis Lamar, courtesy of Tim Shank ’88. ©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

What does it take to study the deepest places on Earth? The same kind of mettle required to survive them. Tim Shank ’88 has spent a lifetime doing both.

by Beth McNichol ’95

From a research vessel floating off New Zealand in May 2014, deep-sea biologist Tim Shank ’88 watched as 10 years of his work resurfaced in the Pacific Ocean, piece by agonizing piece. This was the pioneering robotic sea explorer Nereus — or what was left of it — broken and beaten and returning home from one of the deepest places on Earth.

Two days earlier, Shank, a tenured scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, had sent Nereus 10,000 meters down into the Kermadec Trench. The robot’s mission was to explore the trench’s inky darkness — a watery basement that’s home to hustling amphipods and other near-alien overachievers who survive where humans and even most fish cannot. Scientists labeled the area of the ocean below 6,000 meters the hadal zone for good reason; the pressure increases to levels so inhospitable that neither man nor machine had ever done meaningful research there. The deepest hadal trenches boast 16,000 pounds of pressure per square inch, a force equal to 1,000 Earth atmospheres — or, as WHOI engineer Andy Bowen put it, three SUVs sitting on your big toe. Like the Greek god of the underworld for which it was named, the hadal zone, which comprises 45 percent of the ocean’s depth, remained unseen.

But Nereus had changed all that. It was an unmanned, hadal-pressure-tested wonderbot that could move autonomously over the seafloor while it mapped and transmitted live video back to the ship. Or, a remote pilot could direct its path and ask its manipulator, arcade-claw arm to take samples from the last unexplored frontier on the planet.

Nereus was an oceanic moonshot, the Apollo 11 of the seas. In the early 2000s, the knowledge that Russia was diving deeper than the U.S. led the National Science Foundation to fund both Nereus’ development at WHOI and its $1.4 million cruise to the Kermadec. This was an aquatic version of the Space Race, and it was no less challenging.

“It’s probably easier to go and land a vehicle on Mars — and I say that knowing the people who do that — than it is to do some of the stuff we do here,” Shank said.

Nereus already had completed a 2009 test dive to the 10,902-meter Challenger Deep in the Marianas Trench — the deepest point in the world’s oceans. Hadal ocean research finally had the high-profile hero it had long deserved. More importantly for Shank, who is one of the world’s leading marine biologists and one of a handful of researchers studying the hadal zone, Nereus could help answer the questions that had gnawed at him for more than 30 years.

When the deep-sea robot Shank was working with imploded, it captured worldwide media attention. A little later, a grade-schooler recognized him as the mission’s chief scientist. She walked up to him and handed him a $5 bill. “This is for you,” she told him, “to build a new robot.” (Daniel Hentz, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

How does life survive under the most extraordinary pressures imaginable? And what form does that life take?

Those questions had wide-ranging implications for life above sea level. Already, scientists were studying the adaptations of creatures found at 2,500 to 5,000 meters for potential Alzheimer’s treatments. Those deep-sea dwellers had learned to repel the ocean’s crushing pressure by secreting piezolytes, chemical chaperones that glob onto a cell and halt the water inside from escaping. This superpower allows the proteins inside the cells to fold and function normally, creating the difference between life and death. Although fish may be lower on the food chain, these species had solved a problem the human body has not: Protein dysfunction characterizes most human diseases, including Alzheimer’s, multiple sclerosis and glaucoma.

If that sort of novel adaptation was happening at shallower depths, Shank knew that the wonders happening at 10,000-meters-worth of pressure were likely to be mind-blowing.

“I wanted to ask questions about the evolution of life on Earth and how it’s adapted to high-pressure situations, the most extreme environments on Earth,” said Shank, who was leading a brain trust of the world’s preeminent marine biologists into the Pacific to share Nereus’ research debut. “Normally, a cell would never be able to function in that pressure. How does it do it? How do these animals do it? Fish do it, crabs do it, shrimp are doing it. I just wanted to get there and find out.”

With just 10 days left in a cruise that was five years in the making, Nereus had completed successful dives to 6,000, 7,000, 8,000 and 9,000 meters in the Kermadec and filmed dozens of hours of high-definition video. The expedition had returned weird, exciting critters sure to hold evolutionary secrets: Foot-long amphipods that, found anywhere else, would be the size of a flea. Gelatinous, toothless snailfish with giant livers, the deepest-living fish known.

He was moments away from dying. Just minutes out of surgery, he went into septic shock. A quick-thinking nurse rescued him from the abyss, but he was in multiple organ failure.

It had been two years since Nereus. Two years since his father died. Two years since his mother died, in a year that was his annus horribilus. And now, here was Shank, broken and beaten and trying to return home from one of the deepest places on Earth.

And then, at 10,000 meters, the ship’s monitors connected to Nereus went dark. When a series of dead-man switches onboard the robot didn’t execute as they should have — dropping weight so the vehicle would rise to the surface after it lost contact — fear set in. Two days later, grief arrived, along with Nereus’ $9 million debris. It had imploded.

“We watched the pieces,” Shank said, shaking his head at the memory and smiling sadly in disbelief. “We could see it coming up on the surface all around the ship, which is amazing. It was seven miles below, and it came straight up.”

Seven years later, the ashes from Nereus’ demise still fill the spaces, literally and figuratively, where Shank lives. They hide in corners of his office at WHOI, at his home on Cape Cod and in his mind where the mysteries of life — of being alive, in the first place — first took hold as a kid.

“I’ll never get over it,” Shank said. “It still hurts.”

Nereus’ implosion captured worldwide media attention. A month after Shank returned, a grade-schooler spotted him outside of WHOI’s offices and recognized him as the cruise’s chief scientist. She walked up to him and handed him a $5 bill.

“This is for you,” she told him, “to build a new robot.”

He can’t tell that story without wiping away tears — both for the kindness of the girl and the magnitude of what was lost. That’s how it goes for deep-sea scientists: Every day is either poetry or heartbreak, and you’d be a fool to plan for either.

The truth was, he didn’t know when — or if — he’d ever get back to the hadal zone. But he did know that the struggle to adapt to a life lived at great depths, to survive under pressure, was not confined to the sea.

And Tim Shank would soon face the fight of his life.

A dive into the abyss

He was lying on a gurney in the hallway outside of the emergency room when he started gasping for air. Tim Shank was moments away from dying.

Hours earlier, he had arrived by ambulance dehydrated, nauseated and in severe back pain due to what doctors said was a blocked kidney stone. Just minutes out of surgery, he went into septic shock. A quick-thinking nurse rescued him from the abyss, but he lay unconscious and on a ventilator. He was in multiple organ failure.

It had been two years since Nereus. Two years since his father died. Two years since his mother died, in a year that was his annus horribilus. And now, here was Shank, broken and beaten and trying to return home from one of the deepest places on Earth.

Like Nereus, he took his time.

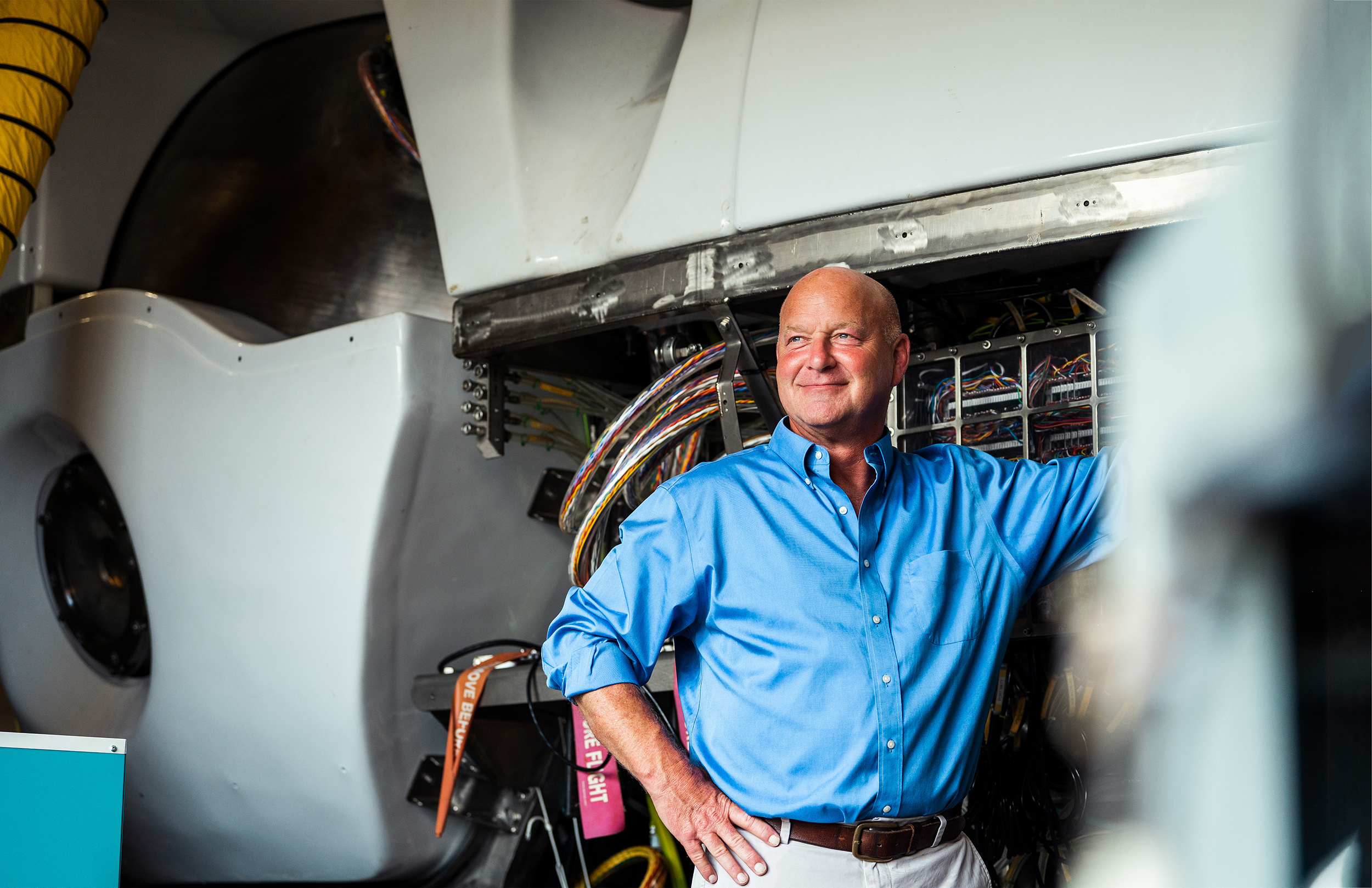

Shank in the first manned dive to the bottom of Lydonia Canyon, 100 miles off the coast of Massachusetts. NASA wants to one day explore the oceans on Europa, Jupiter’s icy moon, where Shank believes some form of life is likely to exist. But first, science must master underwater exploration and understand the life that already rolls in the deep, cold ocean trenches of our own planet. That’s where Shank comes in. (Luis Lamar, courtesy of Tim Shank ’88. ©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

It seemed the universe had always called on the Shank family to plunge into life’s trenches, to be shocked by the cold depths and kick their way back to the surface, stronger. He was 10 when his father left, and that was how he discovered the first great evolutionary marvel of his life: His mother.

After Barry Shank, a music professor at East Carolina, walked out, Terry Shank became the sole provider for their three sons. She was a piano and violin teacher who had once been a member of the Birmingham Symphony, but she adapted to become many things in her husband’s absence: The first woman to chair the board of education for Greenville City Schools. Delegate to the United Nations World Conference on Women in China. Member of the Pitt County Board of Commissioners. Two-time breast cancer survivor.

The harder life pushed Terry Shank, the taller she stood.

But there was one thing she could not do. She couldn’t fully heal the pain of Barry’s retreat. When her oldest son, Michael, was a junior biology major at ECU, he was arrested for cocaine trafficking. Decades later, Michael told The News & Observer that his father’s absence had in part led him to pursue a lifestyle that morphed from doing drugs in his teens to selling them in college.

Tim was 15 when Michael was convicted and sentenced to nine years in prison. He served four years and called home nearly every day with terror in his voice, convinced he would be framed for more crimes and never get out. The stress of it all nearly drove his mother over the edge.

Tim missed the brother who once investigated intertidal creatures with him on vacations to the Outer Banks. He missed him so much that, although Tim was not an athlete — he was a talented theater kid who sang, performed in musicals and played multiple instruments — he joined the high school football team.

“Michael could listen to the radio at night, quietly,” Tim said. “He would tune into the AM station and listen to the broadcast of the games from his cell. I said, ’If I can start and make tackles, he will hear them call my name out, and he’ll know that I’m at the game.’ That was the only way that I could interact with him.”

You want to talk about surviving at great depths? The hadal zone had nothing on the Shanks.

After his release, Michael eventually regained his sobriety and his compass. (Now a physical therapist, he founded a nonprofit that helps ex-felons rebuild their lives, and he received a pardon from Gov. Mike Easley ’72 in 2001.)

But the tumult Tim witnessed during his teenage years steered him to overcorrect. He was determined to “do the right thing” — even if it felt all wrong. At Carolina, he enrolled pre-med. It was a disaster. He struggled in his science and math classes, earning 11 percent on one final exam, and switched his major to international relations. He was inches away from attending law school when the ghosts of those intertidal creatures intervened.

The tumult he witnessed during his teenage years steered him to overcorrect. He was determined to “do the right thing” — even if it felt all wrong. At Carolina, he enrolled pre-med. It was a disaster. He struggled in his science and math classes, earning 11 percent on one final exam, and switched his major to international relations. He was inches away from attending law school. “I couldn’t do it,” he recalled. “The most important thing was life itself, this amazing thing called life. … I’d always been fascinated by it. We’re talking, we’re moving, and then there’s a point where we stop being alive. What’s more important than understanding that?”

“I couldn’t do it,” he recalled. “The most important thing was life itself, this amazing thing called life. … I’d always been fascinated by it. We’re talking, we’re moving, and then there’s a point where we stop being alive. What’s more important than understanding that?”

Shank couldn’t stop thinking about an evening lecture he’d attended by UNC marine sciences Professor Conrad Neumann. The Cape Cod native — a gifted artist and poet who brought an English major’s soul to oceanography — had recently dived in Alvin, the three-man, deep-sea research submarine that has been operated by WHOI since 1964. He returned to Carolina with far-out tales of organisms that dined off the bubbly spigots at hydrocarbon seeps, 3,200 meters under the sea. Seeps and their counterparts, the volcanically driven hydrothermal vents, emerge from the seafloor due to tectonic shifting; they produce gaseous and mineral-laden fountains from which microbes feed. These microbes, in turn, nourish the animals that have evolved to live in the near-freezing darkness, far from the photosynthesis that humans, most fish and other species depend on for life.

In other words: They are the closest thing to an alien colony that we have on Earth.

“That was it,” Shank said. “I was done. The lure, the romanticism … it was all there.”

Shank followed Neumann back to his office and told him he wanted his job.

“You can’t have my job,” Neumann replied. And then: “If you care about marine biology, go out and learn something different first, and then bring that skill back to the field. Don’t go looking to pet the dolphins.”

What keeps Shank going is the knowledge that he’s building a future in which deep-sea robots will spread out across the ocean’s trenches, comprehensively mapping the seascape. Meanwhile, remotely operated vehicles will grab tools from landers placed along the seafloor. Working in concert, the vehicles will — one day — return with amazing critters from the deep that Shank can genetically sequence. (Luis Lamar, courtesy of Tim Shank ’88. ©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Shank’s admiration was so deep, he would have opened a seafood restaurant if Neumann had suggested it. He dove into genetics at the Environmental Protection Agency in Research Triangle Park while completing the chemistry and physics classes he needed to get into graduate school.

When he landed a spot in the marine sciences doctoral program at Rutgers, he studied hours of video recordings taken after a 1991 underwater volcanic eruption in the East Pacific Rise, 500 miles southwest of Acapulco. The event had decimated the animals who lived there. In 1993, he took his first deep-sea plunge in Alvin to investigate what had changed at the site since.

“It was like paving down a forest and then looking at how things come back,” Shank said. “No one had done that before.”

Shank’s excitement aboard Alvin’s cramped, 6-foot-diameter capsule earned him the nickname Jimmy Olson. Like the freckle-faced photojournalist from the Superman comic books, Shank could not contain his enthusiasm. Less than a decade earlier, he had listened to Conrad Neumann speak of his travels in the famous submarine; now, he was face-to-face with the ocean through Alvin’s portholes. Dan Fornari, research scholar emeritus at WHOI and a marine geologist, was with Shank that day.

“Diving in the Alvin can be a very Jules Verneian experience and very formative,” Fornari said. “It’s a little like somebody telling you, ‘Well, would you like to go to the moon tomorrow and walk on the surface of the moon?’ It is very remote, and it is very hostile in a certain sense. It’s not a place where humans are naturally supposed to be. All of that excitement comes to the fore.”

If Shank wanted to see how life persisted after calamity, he’d come to the right place. Far from remaining barren, the area had repopulated quickly over 18 months with different, fast-growing invertebrates. The deep sea wasn’t slow-moving at all; despite the cold, the dark and the pressure, communities grew there at lightning speed, like tract homes going up in suburban America. The NSF called it “one of the most dramatic underwater discoveries in history.”

Life was abundant again, both for the East Pacific Rise and for Shank.

That dive was the first of more than 100 Shank has taken in Alvin — he now ranks among its top five all-time research passengers. It also launched him at WHOI, where he earned a postdoctoral fellowship shortly after the research was published in Nature. He has been there ever since, rising through the brutal WHOI tenure process while producing pivotal work on hydrothermal vents, coral reef communities, the evolution of deep-sea life — and, of course, the hadal zone. Nereus.

He would never forget Nereus.

Orpheus rising

Shank awoke in the hospital four days after his sepsis crisis, with vivid memories of nearly dying. He had been lucky; sepsis patients are always the sickest in the hospital, and doctors had given him only a 30 percent chance of survival. Still, he spent the next month at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston recovering and the next six months away from WHOI, unmoored from all he knew.

Many people who go through a near-death experience like Shank’s wrestle with the aftermath. Often, they struggle to find their purpose. Shank has had five years to reconcile it, and for him, it comes down to this: What do you do with the rest of your life when you already know what the end looks like? What do you do when you know that everything will be OK?

You go back to chasing your deepest dream imaginable.

Now, Shank is building a new version of that dream with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The people who brought the Perseverance rover to Mars are now helping Shank perfect a new hadal zone robot. Like the Perseverance, WHOI’s new submersible features Terrain Relative Navigation, the software that enabled the rover to safely land, with pinpoint accuracy, by taking images of Mars’ surface as it approached.

It’s a marriage of convenience. NASA wants to one day explore the oceans on Europa, Jupiter’s icy moon, where Shank believes some form of life is likely to exist. But to do that, science must first master the challenges of underwater exploration and understand the quirky life that already rolls in the deep, cold ocean trenches of our own planet. That’s where Shank and Orpheus come in.

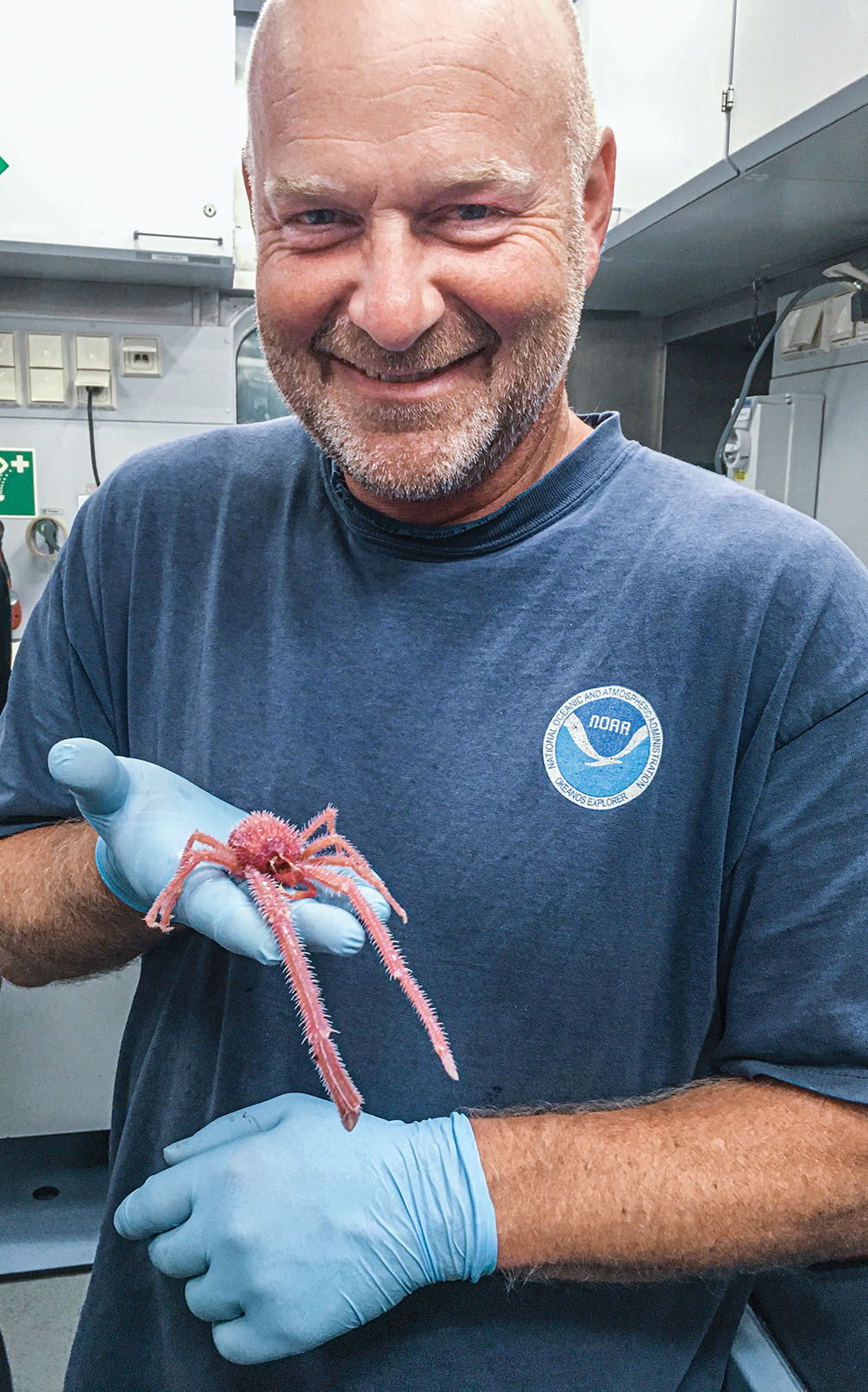

Shank holds what is considered to be a new species of crab discovered in 2017; the creature was living on a black coral colony more than 4,000 feet below the surface. It was collected by the remotely-operated vehicles on board the research vessel Falkor. (Courtesy of Tim Shank ’88)

Named for a figure in Greek mythology who made it to the underworld and back, Orpheus is not the new Nereus. The strictly autonomous vehicle is a fraction of its predecessor’s weight and cost (minus JPL’s $50 million software) — the better to one day launch into space. And even with its bells and whistles, in its current form, it cannot systematically study the ecosystems of the world’s ocean trenches in the same way Nereus could have. It has no manipulator arm to grab samples.

That hurts Shank’s soul just a little bit.

What keeps him going is the knowledge that he’s building a future in which Orpheus and its progeny will spread out across the ocean’s trenches, comprehensively mapping the seascape. Meanwhile, remotely operated vehicles will grab tools from landers placed along the seafloor. Working in concert, the vehicles will — one day — return with amazing critters from the deep that Shank can genetically sequence.

The bot has backing: OceanX and Bloomberg Philanthropies have invested $185 million in Orpheus’ research. Meanwhile, the JPL partnership allows ocean exploration to ride the flashier publicity contrails of NASA, whose annual budget, Shank notes, could fund 340 years of ocean research. That exposure is vital; what Shank has learned in just the past decade about the future of our oceans should have us all sitting at attention.

It’s not just the fragility of coral reefs, about which Shank’s lab is a leading investigator; it’s the life-support system they provide for other animals in the ocean and, in turn, us. When they are destroyed, they take with them entire ecosystems of species.

It’s not just the push to mine the deep sea for metals that build our electronics; it’s the organisms and microbes that live on those nodules, how removing them means removing infinite possibilities for understanding our relationship to the ocean. It’s the way the warming ocean will, one day soon, irreversibly change the animals who live there … the way it has already begun to.

Shank’s pulse quickens when he thinks of the wonders still to be found and the limited time he has left to discover them.

“The deep sea is a place of mystery, a place we don’t know that much about,” Shank said. “But we know enough to know that it is pretty freaking awesome. And a lot of the issues that we have on land can be helped by the deep sea, beyond pillaging seamounts for cobalt.”

Shank’s work is stored in his bones and settled on his heart. At 56, he still speaks of it all with the enthusiasm of Jimmy Olson. Yes, there are days, he says, when he wonders what it’s all for, if anyone out there is listening. Days when he longs to simply sit and play the piano like he once did, to feel the music the way he feels the ocean calling.

But the deepest places in the sea have the power to teach us how to live on solid ground. And what’s more important than that?

“It could be a long time before we get there,” Shank said. “But, do I think I’m going to get back to the hadal zone? Yes. Because I’m not going to stop until it happens.”

—Beth McNichol ’95 is a freelance writer based in Raleigh and a former associate editor of the Review.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.