He Put It All In

Posted on May 7, 2021

(Grant Halverson ’93/Getty Images)

Roy Williams ’72 never disappointed the journalism class, even after a long, sometimes frustrating practice. He’d promise them 15 minutes and give 45.

by Tim Crothers ’86

I asked Coach for 12 hours.

I knew that was a conservative estimate for a man to tell his life story, especially a man like Roy Williams ’72 (’73 MAT). But I also knew that Coach lived by the clock and never had enough time, so I’d better not ask for too much. Yes, I’ll call him Coach in this story because that is what I’ve always done. Coach respectfully addressed his mentor, Dean Smith, as Coach, and so how could I not do the same with him?

On the sideline with grandson Aiden. (Grant Halverson ’93/Getty Images)

I barely knew Coach before the summer of 2009, when I asked for those 12 hours of interview time to help him write his autobiography. For some reason, he trusted me.

He invited me to his home in Chapel Hill, and we sat down at a glass table in his sunroom. I arrived with a page full of questions. I asked one. Coach talked for four hours straight about his hardscrabble childhood in the mountains of North Carolina. The next night, he picked up right where he left off and continued chronologically from there. At the end of our third night together, he hadn’t even reached the part of his history when he left Kansas in 2003 to accept the head coaching job at UNC. I knew that was a problem. Coach trained his gaze on me, clearly amused by my obvious discomfort.

“Tim, how many hours did you say you’d need?”

“I believe I asked for 12, Coach.”

“How many have I given you?”

“That would be 12, Coach.”

“Are we done?”

Coach knew the answer. I felt like one of his players who’d shown up late for the team bus. I thought back to the fact that Coach hadn’t exactly embraced my proposal for this project in the first place because he couldn’t imagine anyone actually wanting to read a book about him, and so I wasn’t really sure how this was going to end. Coach was preparing to send a message.

“Tim, if we’re going to do this, I’m going to do it all in. I’ll see you tomorrow night.”

At “Late Night With Roy,” he danced with … well, the players couldn’t always find the words to describe that. (Grant Halverson ’93/Getty Images)

So I showed up the following evening, and Coach gave me four more hours. As I was packing up around midnight, he asked me again what would become a very familiar question: “Tim, how many hours did you say you’d need?”

“I believe I asked for 12, Coach.”

“How many have I given you?”

“That’s 16, Coach.”

“Are we done?”

“Not yet.”

“OK, I’ll see you tomorrow night.”

And so it went. Night after night after night after night, sitting together at that glass table. Coach’s wonderful wife, Wanda ’72, sometimes pulled up a chair with us, offering me snacks, drinks and ideas for stories to plumb. An idol became more human with every passing hour.

Of his original Kansas decision, he said: “The family said, ‘Why don’t you come back and be a part of the family business?’ And the guy said, ‘No, I’ve got this thing going, and I’m really pleased. This is what I want to do.’ ” (Grant Halverson ’93/Getty Images)

Coach told me about growing up part of a family rife with outlaws and drunks, included among them his own father, Babe, and he told me about his mother, Lallage, whom he described as his “angel,” and he told me the iconic story about how his mom had once learned that after playing pickup basketball in the afternoons, young Roy would drink water while his friends sipped Cokes and how, after that, though she was dirt poor and worked multiple jobs to barely keep her two children clothed and fed, she left a dime on the kitchen table every day so that her son could enjoy a Coke with his buddies, and he told me about how as a young assistant coach at UNC he sold 55,000 calendars one summer to support his own family, and he told me his decision to leave Kansas for UNC truly involved more than just Coach Smith calling him home, but that he’d missed the passing of his mother while on a recruiting trip and vowed to be closer to his father and sister for the rest of their lives, and he told me about the immense responsibility he felt to win a national championship for Tyler Hansbrough ’09 and how he promised himself he would never retire without thinking long and hard about how Coach Smith once confessed to him that he’d quit too soon.

At the end of our final interview, Coach pulled out his wallet. He showed me a folded, dog-eared $100 bill. He said he got it from a friend of his mother’s the day after she died. The man said that Lallage had won it playing bingo and that she wanted her son to have it. Coach put the bill in his wallet that day where it had stayed for 17 years. “Whenever I see it there it reminds me that if there’s ever a really, really, really rainy day,” he told me, “I’ll be all right, because my mom will still be leaving me that dime.”

I don’t think Coach would mind me sharing that he cried while he told that story. So did I. Coach slipped the bill back into his wallet, composed himself and then stared back to me. “Do you know how many people know that story?”

I tried to reply, but my voice failed me.

“Three. Me, Wanda and now you.” I understood in that moment that he’d put it all in.

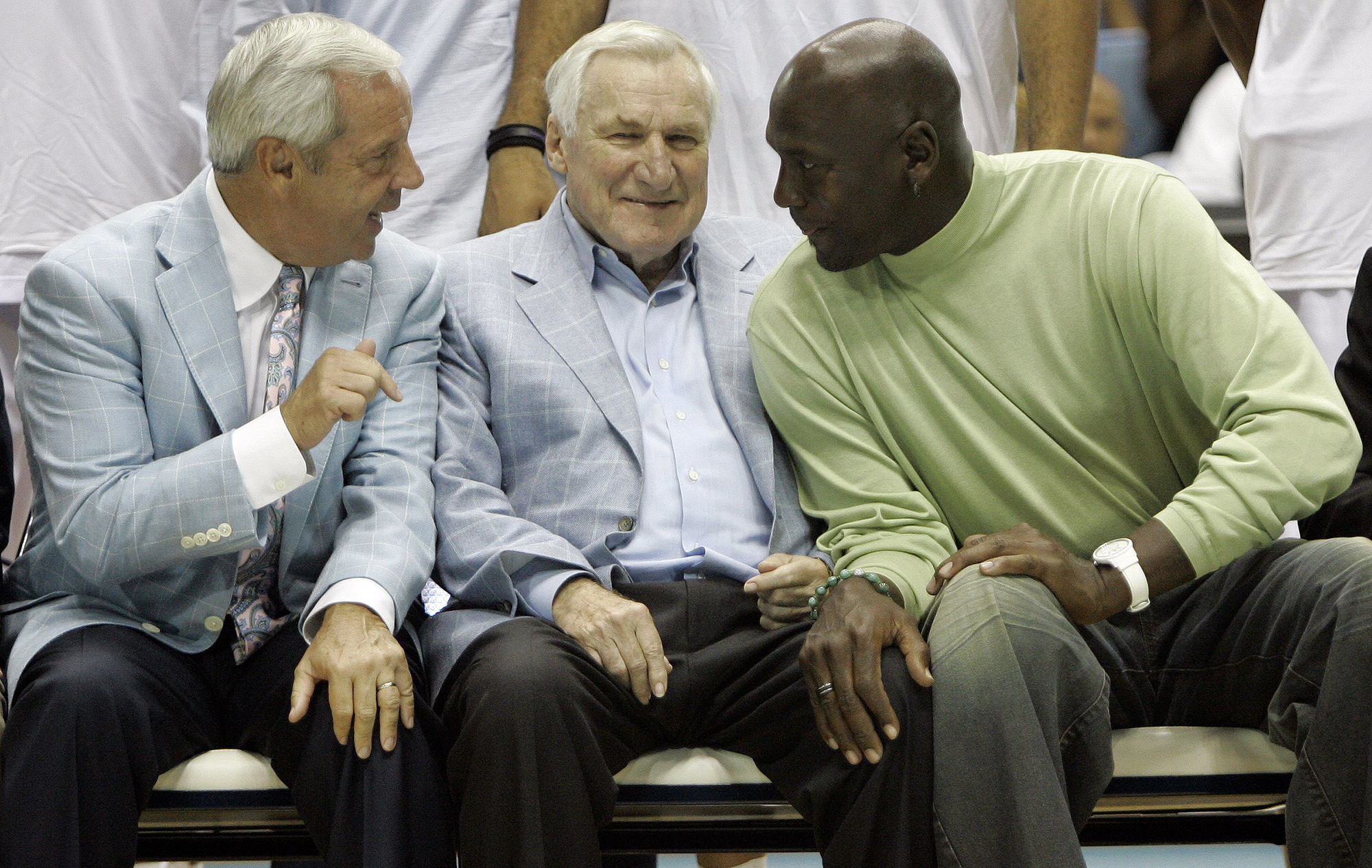

a reunion in the Smith Center with Coach Dean Smith and Michael Jordan ’86, who said in April: “To choose your own path, to walk away from the game when he wants, it’s great he now gets to spend more time with his children and grandchildren. I’m sad that he’s leaving, because he has meant so much to basketball.” (AP Photo/Gerry Broome)

Coach had given me a total of 64 hours. We titled his book Hard Work because those were the last two words chanted at the end of his UNC basketball huddles. And because Coach embodies that phrase. Even Hard Work took hard work. We completed the entire book in two months. It became a bestseller. Because Coach had put it all in.

Every year after the book was published, I would bring my UNC journalism class to the Smith Center one Monday each fall semester to meet with Coach. I often had 50 students, and nobody ever skipped that class. It took me a few years to notice that there probably were even a few extra sometimes. We always went near the start of the basketball season, and Coach would be coming off the court after a long, sometimes frustrating practice. He often still had a radio show to do that night. Our Q&A would be scheduled for 15 minutes. He’d give us 45.

A goodbye hug for Joel James ’16. (Grant Halverson ’93/Getty Images)

I never stopped reminding myself that Coach didn’t have to do this, but he once told me that working at the Smith Center on the southern edge of campus could feel isolating at times and that he relished these encounters with “regular students” as a chance to sneak outside the insular UNC basketball bubble for a moment. My students would dutifully ask Coach about his relationship with the media, and he would deliver strategic responses — not so much as the leader of the Tar Heels, but more as a father figure, every answer carefully tailored to send a larger message than the question required.

My favorite part of those meetings with Coach would be scanning the faces of my class, many slack-jawed and astonished by the experience of sitting in the Smith Center press room talking to a legend. On one of those evenings, I walked out into the November night a few paces behind one of my students. She was on the phone with her father. Her voice cracking through tears, I overheard her say: “Daddy, you won’t believe this. … I just talked to Roy Williams. It’s the most amazing thing I’ve ever done.”

We asked Coach for 18 seasons. He gave us 485 wins, including three national championships, more than any other coach during his tenure. But more importantly to him, on and off the court, he gave us his best every minute of every single day.

In a season of unimaginable difficulties with the coronavirus pandemic, the 900th career win. (Grant Halverson ’93/Getty Images)

As I watched his emotional retirement press conference in April, I couldn’t help but think that Coach had put it all in. In the back of my mind, I heard the echo of his voice with that distinct North Carolina mountain accent asking another familiar question:

“Are we done?”

Yes, Coach. Thank you.

Tim Crothers ’86, a lecturer in UNC’s Hussman School of Journalism and Media, is the author of three books and hundreds of stories for Sports Illustrated.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.