Healing Wounds & Soothing Scars

UNC’s Jaycee Burn Center has thrived in part because of an imaginative approach to expanding its mission beyond the aftermath of a terrible moment.

by Brian Freskos ’15

The patient’s left arm hangs at an angle from a metal pole. With machines beeping and overhead lights glaring down, Dr. Bruce Cairns unwraps a bandage from the patient’s wound, revealing white, blistery skin stretching from the forearm to the palm.

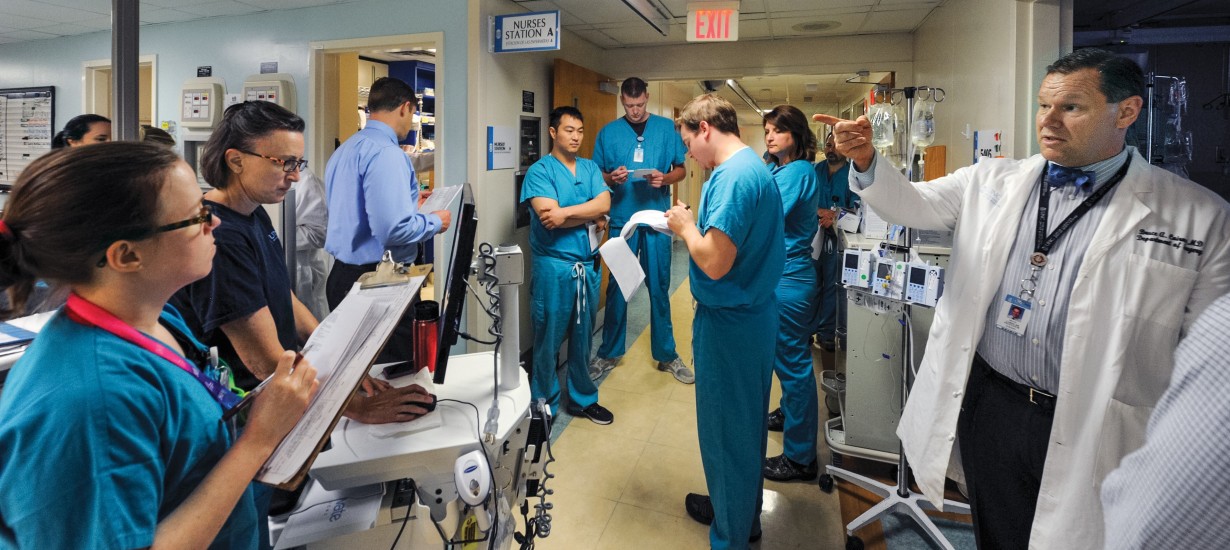

Dr. Bruce Cairns and Dr. James Hwang operate on Charlie Davis, whose arm was injured after being caught in a conveyor belt, at the N.C. Jaycee Burn Center. (Photo by Donn Young)

“We’ve made amazing strides in our laser therapies and reconstruction therapies and things like that to get somebody more functional and get wounds to look better, but it’s still forever. And that is hard,” says Dr. Felicia Williams ’05 (MD), one of the core burn center physicians. (Photo by Donn Young)

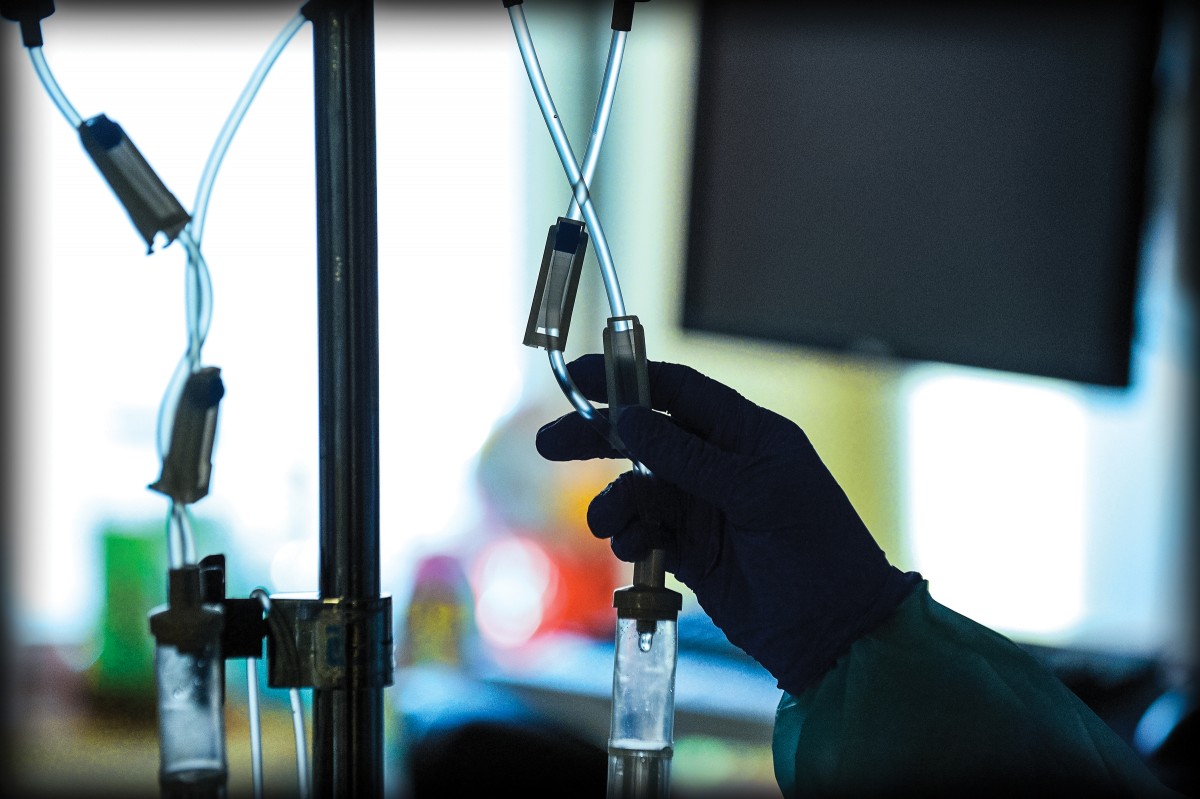

Cairns and a colleague, Dr. James Hwang, spend several minutes slicing off the patient’s burn with a small, razor-sharp knife. The cuts slowly reveal muscle and a river system of blue veins. Next, the doctors go to work on the man’s leg, using what could pass for a fancy upholstery brush to trim a thin layer of healthy skin from his thigh. They place the healthy skin over the gap in his arm, cover the patch in his leg with pigskin and wrap him up again.

The surgery lasts about an hour. The surgeons, nurses and other medical staff perform so many operations each year that they have their craft down to a routine. There is little talking; everyone just seems to know what to do and when to do it.

The North Carolina Jaycee Burn Center, which Cairns has directed for nearly a decade, sees all manner of burn injury. This morning’s patient, Charlie Davis, 47, got his arm stuck in a conveyer belt at a tire plant in Danville, Va.

Also in the burn unit that day were a husband and wife — a propane tank exploded on their boat. And a man who had been setting debris alight in his backyard when a gasoline can exploded in his hand. And a baby who fell into a fire pit.

On a different morning, Cairns strode the hallway in his customary white jacket and bowtie, calling out the day’s cases: “Electrical, scald, clothing catching on fire. … You can see, each one of our patients is a story in itself.”

The burn center frequently operates at capacity. The center’s pastor has married couples in the chapel and baptized people in the metal beds used to give patients baths. Anita Fields ’86, a former nurse who now runs the center’s aftercare program, said she and her colleagues have held memorial services for patients’ lost limbs, dogs and — once — a cow. One patient called her months later to say she had named her daughter Anita.

Davis’ experience is emblematic. He likely will need therapy, lest his hand stop functioning, and possibly more surgeries. After he goes home, he could be returning to the burn center for years. Some patients access aftercare services for a lifetime.

“We’ve made amazing strides in our laser therapies and reconstruction therapies and things like that to get somebody more functional and get wounds to look better, but it’s still forever,” said Dr. Felicia Williams ’05 (MD), a burn center physician. “And that is hard.”

With 36 beds, it is a small part of UNC Hospitals, which has more than 800 beds and includes hospitals specific to women, children, neurological disorders and cancer. But the burn center punches well above its weight. Besides treating patients from across the Southeast, it has installed burn-prevention programs in schools and nursing homes and has played a role in passing a law to require that tobacco companies make fire-safe cigarettes.

With the help of millions of dollars in grants, it has expanded its reach to Africa. The center has set up a burn wing in Malawi, where UNC has a long-standing medical research presence, and to a burn-prevention program in South Africa.

Operating room at N.C. Jaycee Burn Center (Photo by Donn Young)

The most challenging problems

In the 1970s, John Stackhouse, an electrical contractor in Goldsboro, started trying to turn his dream for a burn center into a reality. He was inspired after several of his employees suffered burns on the job. Stackhouse kicked in tens of thousands of dollars and prodded other organizations to do the same. Cairns remembers buying jars of jelly that local Jaycee and Jaycette chapters sold in the 1970s to raise money for the project.

The burn center opened in 1981, when Cairns was about 18. He was beginning to understand what the University meant to the state, the relationship it had with the people. “It was clear, even as a young person, that this was something that was driven by this sense of need and sense of compassion for others,” Cairns said, “and that this is what people do, is that we take care of each other and that the University is a place for that.”

Cairns’ family had moved to Chapel Hill from Indiana when he was 10. He stayed until college, leaving to get his undergraduate degree from Johns Hopkins University and then go to medical school at the University of Pennsylvania. He rotated through the burn center for the first time after returning to UNC to complete his postgraduate training. He loved the center’s multidisciplinary nature. Doctors, nurses, therapists, social workers.

Cairns wasn’t sure which area of medicine he wanted to focus on. But he knew he wanted to treat patients with some of the most challenging problems. There’s a case from his first rotation at the center that sticks with him. He remembers a 13-year-old girl who came in with Stevens-Johnson syndrome, a rare disorder caused by a drug reaction. All her skin had come off; he knew her chance of survival was low.

“But you could tell that her mom, I mean this was the world to her mom, and how hard this was for her,” he said. The girl eventually died from the disorder, and the experience struck a chord with Cairns — the burn center is a place where doctors deal with tragic problems.

The patients there “were really sick. They were sick for a very long time, and they were very challenging to deal with. And it was horribly tragic.”

After his rotation, Cairns left Chapel Hill for a second time to serve in the Navy in Guam. He was there when Korean Air Flight 801 crashed on a runway, killing 228 passengers. Some of the survivors came under Cairns’ care. The crash cemented his interest in burns, he said, as if God was “trying to tell me what I’m supposed to do.”

Cairns left the Navy in 2005 after 19 years as a commissioned officer. But his passion for the military continued. In 2008, he traveled with colleagues to Fort Bragg to learn about the needs of special forces medics. About a year later, he helped launch the Advanced Medic Instructor Training program to help returning medics develop civilian careers.

By then, he was director of the burn center, which he has led in several directions beyond emergency care and physical healing. His passion for service now crosses over to the administrative side of the campus. In 2014, Cairns was elected to a term as chair of UNC’s faculty. “Why do something like this?” Cairns said about pursuing an administrative job that can be consuming. “I think it should be to serve, and I think it’s important to serve when things are tough, and also to create an environment for people to have conversations about difficult things with no clear resolution.”

Anita Fields ’86, a former nurse, runs the center’s aftercare program, which in 2008 became a separate unit. Expanding beyond emergency care has been key in the burn center’s success in a financially challenging field of medicine. (Photo by Donn Young)

Stretching the center’s reach

Anita Fields said that after she started as a nurse in 1986, the staff played checkers because the center had so few patients. That never happens today. Admissions have more than doubled since Cairns took over in 2007, shooting from 690 that year to 1,518 in 2014. The center takes care of so many patients that sometimes it can’t fit them all in its two wards.

“I think they’re keeping up with demand but only just barely,” said Tim Bradley, a burn center advisory board member and executive director of the N.C. State Firemen’s Association. Bradley, who once was briefly treated at the burn center after rescuing a 5-year-old boy from a fire, said, “I think you rarely find a time when they’re not full to capacity and even using other critical-injury areas to house patients.”

Part of the spike is a side effect of North Carolina’s booming population. But a bigger factor, many say, is the burn center itself. Officials in recent years have spent more time reaching out to other hospitals, spreading awareness about everything the burn center offers. As a result, transferals have boomed as patients — who previously would have stayed in some other county — are being taken to Chapel Hill.

In fall 2012, UNC opened the Burn Reconstruction and Aesthetic Center, where doctors reconstruct ears, noses and other casualties of burn damage — and do whatever else it takes to make patients more comfortable, improve their functioning and ease stiffness from scars. Dr. Scott Hultman ’08 (MBA), who is both a plastic surgeon and associate director of the burn center, said the aesthetic center gets six or seven patients a week from the burn center, some of whom are scarred over 75 percent of their bodies, and works to get them back to work and school and life in general.

The aesthetic center is about to begin a new study that could help burn patients become more comfortable in their daily lives. Fat transfers — literally sucking fat out of one part of the body and injecting it somewhere else — have been standard fare in the cosmetic world for some time. In more recent years doctors like Hultman have learned that injecting fat cells underneath scar tissue loosens up skin and reduces pain, but there has been little formal research on how well the technique works with burn patients.

This fall, Hultman and his colleagues hope to start closing that gap. They will be surveying some 30 patients to find out whether their pain abated after undergoing a fat graft. In addition, the researchers will assess the patients’ scars for changes in color, pliability and thickness to see whether the operation resulted in aesthetic improvements as well.

“I hope at the very end of all this that we will be able to find a way to help patients with their pain,” Hultman said, noting how some patients can’t move because their scars cause wrenching pain. “We’re just looking for anything that we can do to help these patients.”

“Because there’s no limit to the tragedy, there’s no limit to the challenge, there’s no limit to the field that needs to be improved,” Dr. Bruce Cairns, director of the N.C. Jaycee Burn Center, says about treatment of burn injuries. (Photo by Donn Young)

More recently, Cairns and his staff have been working on a soon-to-be-live telemedicine program, so doctors at other hospitals can call the burn center for advice in treating patients. The program is aimed at ameliorating a shortage of specialized burn-care facilities, a dearth that keeps many patients from getting special treatments and resources.

The telemedicine program is one example of how the Jaycee Burn Center is expanding its reach even as other burn facilities have scaled back or closed. Cairns said there are fewer burn beds in the U.S. now than 10 years ago. The American Burn Association lists 62 centers nationwide — 21 states, several of which are in the Southeast, have no burn centers. Hultman said small centers find they can’t afford to stay open because the cost of maintaining accreditation is too high.

Dr. Brian Goldstein, UNC Hospitals’ chief operating officer, when asked why North Carolina felt it was important to operate a burn center when other states did not, said: “I think if you want to be a flagship hospital and a public academic medical center for the state and the Southeast, you have to be willing to provide services that are not necessarily sexy or the most easily profitable.

“They’re services that the public doesn’t often think about until a disaster occurs or there’s a big factory fire,” he added, “but it’s really important to have those world-class services available when people need them.”

Burn care has advanced exponentially in the past few decades. Shirley Massey, the burn center’s coordinator of adult aftercare and spiritual support, said when she started working in the burn center in the late 1980s, she heard patients screaming in pain as she walked the halls. Pain remains a serious issue, but changes in medicines mean today’s patients are more comfortable than those of 30 years ago. Still, challenges remain, which is why Cairns has assembled a team of academics to boost the burn center’s focus on research.

“If you were looking for a field that needed people to care and needed people to help you, and you wanted to take care of the critically ill, and you really wanted to go all in, there’s no better place than this,” Cairns said, “because there’s no limit to the tragedy, there’s no limit to the challenge, there’s no limit to the field that needs to be improved.”

Housing the ICU in the hospital enables Cairns’ core team of burn physicians — including Hwang, Williams and Samuel Jones ’95 (MD) — to bring the system’s resources and expertise to bear on each patient, with consultations from cardiologists and other specialists.

Among the conversations are how to facilitate patients’ long-term mental and emotional recovery even after they leave the hospital. Victims of burns that might have been fatal a few years ago are surviving now, and they are returning to a world where scars and disfigurements may make them outcasts. Massey said patients once used the term “social death” to describe the challenges they faced.

To address this issue, the burn center has developed a range of programs known collectively as “aftercare.” The first aftercare program, started in 1982, was a weekend camp for burned children and is believed to be the first such camp in the U.S. Later, annual patient reunions and weekend retreats for adults were added. The burn center was also one of the first places to pilot a peer-support program to connect newer burn survivors.

At first, staff coordinated aftercare programs largely after hours. In 2008, Cairns decided to make aftercare its own unit and tapped Fields to be its director. One of the unit’s chief duties is fundraising; donations and the burn center’s endowment, not the hospital, pay for all programs.

Hultman has worked as a consultant at other burn centers across the country that aren’t doing well. UNC’s center not only has grown, he said, but has improved at lowering complication rates, increasing survival rates and containing costs. Cairns, he said, is “not content with the status quo” — his networking skills are such that he has been able to interact effectively with boards of directors, the media, patients and their families, and government officials.

Terrell Watkins, far right above, reacts after his cabin won the Camp Celebrate 2015 Regatta. Burned as a teenager, Watkins has returned year after year to interact with other burn victims at the Jaycee center’s aftercare camp. (Photo by Kimi Finch)

One moment, a lifetime

When Terrell Watkins was 13, he and a friend tried to set leaves on fire in the woods near his home in Badin. When the pile wouldn’t light, Watkins set a gasoline can on top of it. He lit another match and watched as a spark fell into the can.

The resulting explosion caused third-degree burns to more than 75 percent of Watkins’ body. He ran to his friend’s house and doused his still-searing arm with water. He was transported to the Jaycee Burn Center and spent the next several months recovering.

From Anita Fields, Watkins learned about Camp Celebrate, the burn center’s camp for kids that ran once a year, from one Friday to the following Sunday. Watkins wasn’t comfortable being around so many new faces, but his mom forced him to go. And he said he wasn’t there long before he fell in love with the place. By the end of the three-day getaway, “I was like, ‘I don’t want to go. I don’t want to leave!’ ” Watkins said.

“It really helped me on the process to recovery, to open up.”

Watkins said he didn’t experience much teasing or bullying after his accident, as he was not a “punching-bag type dude.” That’s somewhat unusual, which is why staff members visit schools and meet with teachers and students to ease kids’ transition from the hospital.

His recovery remained a challenge. He endured physical therapy “like crazy.” He underwent dozens of surgeries over two years and could have had many more. Doctors offered to build him a new left ear and correct a droop in his lip. But Watkins was done — he just wanted to get back to being a normal teenager again.

He has spent the past several years teaching children with autism at an elementary school in Fayetteville, and this summer he started a new job as an at-home therapist for kids on the autism spectrum. He enjoys telling his story and doesn’t mind when kids ask about his scars. “They’re kids. They don’t know any better.”

Watkins’ accident happened in 1990. Except for some years working out of state, he has attended every Camp Celebrate since, now as a volunteer. “For some of them, it’s the first time they’ve ever seen a burn survivor like themselves.”

Watkins waded into the crowd as campers arrived for the 2015 season. Bruce Cairns stood there, too, clapping as everyone gathered.

A week later, Watkins reflected on another successful Camp Celebrate. One child’s eyes had watered on the last day, when they showed pictures from the weekend, he said. Another child arrived at camp afraid to show the burn on his stomach. As the boy grew confident, he strutted around with his shirt off.

“That’s what it’s about,” Watkins said.

Ultimately, of course, preventing burn injuries would make this all better. That seems to be about the only thing that would cut down Cairns’ workload. “I have plenty of other things I can do.”

Brian Freskos ’15, a former editorial intern with the Review, is a first-year master’s student in journalism at Columbia University.

Seven years have passed since the gas grill fire that left Cruz Maria Santibanez ’14 a regular patient at UNC’s Jaycee Burn Center, visibly scarred and irrepressibly determined to succeed as a journalist. She’s still pursuing her dream.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.