It Took a Village

(No. 9) President’s Residence, some time between the late 1940s and early 1960s. (Photo: N.C. Collection Photographic Archives)

It is a dignified dwelling, with its two-story Corinthian columns rising behind immense oaks at the southeast corner of Franklin and Raleigh streets. Memories are fading of the time when Frank Porter Graham (class of 1909) threw its doors open to students on Sundays so he could hear what was on their minds.

For 108 years, the president — first of the Carolina campus and then of the consolidated University system — has lived in this one place, and it will have a new resident — Margaret Spellings, its 11th — early next year.

But for the years before 1907, if you wanted to know where the president lived, it would have helped to have had Google maps. Officially, 400 East Franklin is the third president’s house. That overlooks six others.

Joseph Caldwell moved into the house on Cameron Avenue, one of the first three structures the University built, left and moved back in eight years later. David Swain (class of 1825) didn’t want the University-provided second house, then decided 14 years later he liked it. Solomon Pool and Kemp Battle (classes of 1853 and 1849, respectively) preferred the houses they owned and passed on the official residence. George Tayloe Winston, Edwin Alderman (class of 1882) and Francis Venable were left to fend for themselves after the second house burned down.

And most people do not know that the first house, finished in 1795, concurrently with Old East and Steward’s Hall and taken out in 1913 to make room for Swain Hall, was wheeled four blocks over to McCauley Street — and is still there.

Three presidents’ houses? Try nine. Our chief executives didn’t always hang out where the University expected they would.

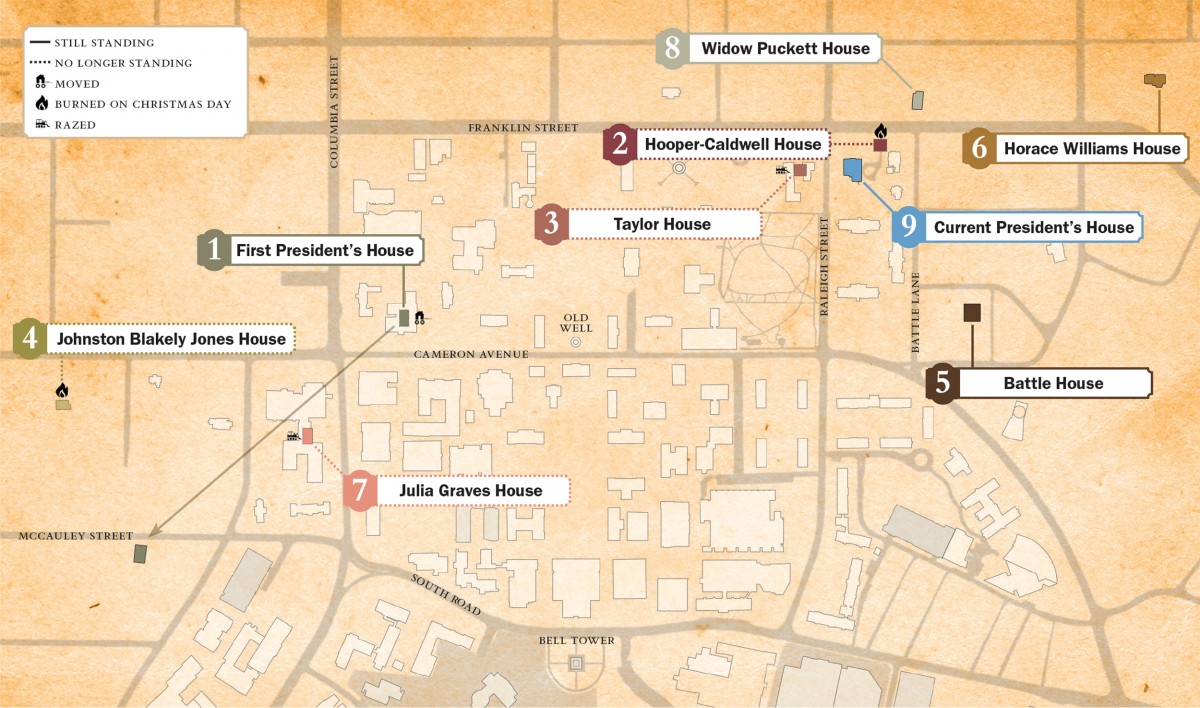

Map to the presidents’ houses (UNC Facilities Services/Jason D. Smith ’94)

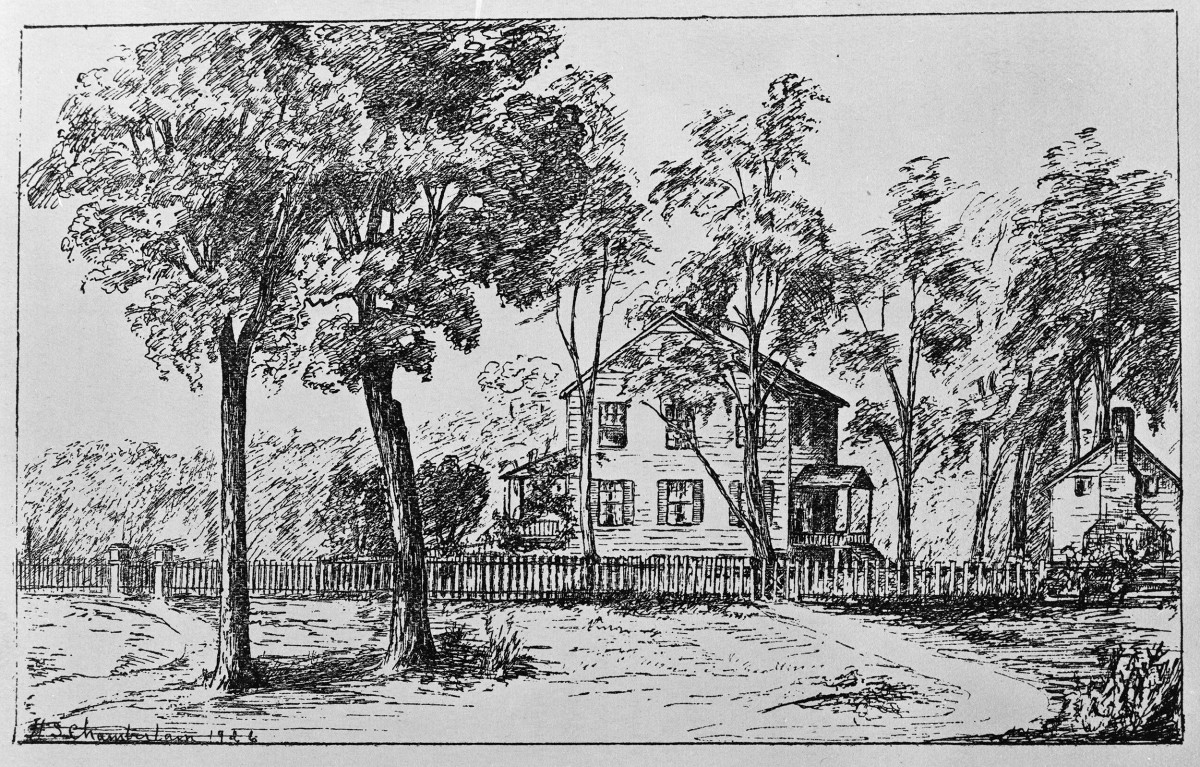

(Hope S. Chamberlain drawing, N.C. Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC)

(No. 1) First President’s House

The house the University built on the present site of Swain Hall in 1795 — seen in the drawing from the east as if standing near Old West — was home to five “presiding professors” in the days before UNC was comfortable conferring the title of president. Joseph Caldwell was first to hold the honor; soon after Caldwell returned to teaching and left the house, things turned ugly around the old place. The unpopular Federalist Robert Hett Chapman attracted tar and feathers and other vandalism from the students. The house now is at peace at 211 McCauley St., where it was moved in 1913. (Photo by Jason D. Smith ’94)

For that first house’s first nine years, there was no president. The original trustees wanted to reserve the authority meant for the president until a suitable candidate was found, and this may have been wise, given the chaotic shifts in leadership that characterized those nine years.

So a succession of presiding professors moved in — David Ker (his strong anti-Federalist views irked Federalist trustees and students, and he was forced to resign); Charles Harris (for six months); Caldwell; and then James Gillaspie, who left for Kentucky following a student rebellion.

Caldwell moved back in, and five years later he earned the first presidency.

A spate of vandalism

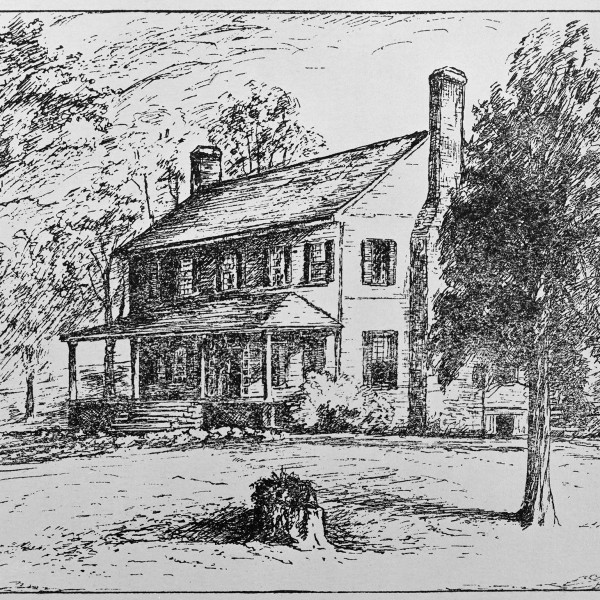

(No. 2) Hooper-Caldwell House

Perhaps the most storied of all the houses, Hooper-Caldwell was Caldwell’s home during his second presidency before it was declared the official residency. His successor, David Swain, didn’t want to live there. Fourteen years later, he changed his mind, and this became the house where, late in his term, his daughter Ella married Union Gen. Smith Atkins. Swain’s successor, Solomon Pool, didn’t want the house either, and a succession of professors lived there. It burned down on Christmas Day 1886, the day after one of them had moved in. The present president’s house eventually was erected immediately to the west of Hooper-Caldwell; artifacts from the doomed house were found during a driveway renovation in 2014. (Hope S. Chamberlain drawing, Archibald Henderson Pictures, N.C. Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC)

After nine turbulent years, Caldwell decided to return to teaching and his astronomy studies. Robert Hett Chapman — like Ker, Gillaspie and Caldwell, a Presbyterian minister — assumed the leadership and the house. Caldwell moved to a Franklin Street house of his own, built about 1811, that would become important when Carolina turned to him again after the Chapman presidency turned sour.

Chapman, a Federalist, was opposed to the war with Britain in 1812. His politics made him unpopular, and the supporting structures of the First President’s House faced the brunt of student anger. In 1814, students broke into the stable and cut off Chapman’s horse’s tail, knocked over an outbuilding and, after removing the gate of his fence, tarred and feathered the gate post. According to Battle’s history of the University, things deteriorated from there.

(No. 3) Taylor House, circa 1912

David Swain moved into Taylor House, the present-day site of Spencer dorm, when he became president; he found the official residence, the Hooper-Caldwell House, unsuitable for raising young children. (History of the University of North Carolina, Vol. II: From 1868 to 1912, Kemp Plummer Battle, pg. 740.)

Chapman decided he’d best leave town, and Caldwell was persuaded to resume his former post. But except for a brief time when Elisha Mitchell lived there as acting president after Caldwell died in 1835, the First President’s House had seen its last. Caldwell stayed at what was known as the Hooper-Caldwell house, which sat on what’s now the driveway of 400 East Franklin. When Caldwell died, the University bought it and declared it the official residence. Only, the next man didn’t want to live there. Swain found Hooper-Caldwell unsuitable for raising young children, so he moved into Taylor House, named for its original owner, which stood on the present site of Spencer dorm.

Meanwhile, William Mercer Green (class of 1818), a professor and Episcopal priest, held down the fort at Hooper-Caldwell. When Green left for Mississippi in 1849, Swain, with 19 years still to go as president, moved in.

This house featured a large porch, a basement dining room and a rooftop platform where Caldwell had taught students about the celestial bodies.

It is where Swain entertained two U.S. presidents, James Buchanan and Andrew Johnson. It also is where he hosted the August 1865 wedding of his daughter Ella to Union Gen. Smith Atkins. The happy couple’s sentiments were not shared in much of the village, which had endured a brief Union occupation after the war’s end.

Swain died in 1868 after being thrown from a buggy which may have been pulled by a horse Gen. William T. Sherman had given him. The next president, Solomon Pool, eschewed Hooper-Caldwell for his own place on the western outskirts of town.

Pool was another unpopular character, elected president at the onset of Reconstruction by a Republican-dominated Board of Trustees. He earned an ample income as both president and as a tax appraiser. In the depressed economic conditions of the 1870s, he acquired some significant real estate, including the Crystal Palace, a Franklin Street boarding house. He owned at least five lots, and at least three of them were on Cameron Avenue.

(No. 4) Johnston Blakely Jones House, circa 1892

This house on West Cameron Avenue was one of several properties owned by Solomon Pool, who earned a salary as a tax appraiser besides being probably UNC’s most unpopular president. It likely is the one he lived in as president, having said no, thank you, to the Hooper-Caldwell official residence. Many years later, in 1928, the house, then the Chi Psi fraternity house, became the second president’s abode to burn on a Christmas Day. Arson was suspected, and according to The Tar Heel, Chi Psi brothers at first were suspected — because they already had announced plans to build the house that now stands on the site — but the state insurance commissioner absolved them of any crime. (“Image 0025: Representative Residences, circa 1892,” in the Kemp Plummer Battle Photograph Album of the University of North Carolina, #P0100, N.C. Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC)

During his presidency, he lived in one of his Cameron Avenue properties, most likely the Gothic Revival Johnston Blakely Jones House, situated on the lot now occupied by the Chi Psi fraternity house.

Pool, hated by many of the University’s alumni and without adequate support from student tuition or state funds, could not keep the University open. It closed in 1871. Pool retained the title of president and lived in his home until 1875, when he moved out of town to become a schoolteacher.

After Reconstruction ended and the University reopened in 1875, a reconstituted Board of Trustees appointed math Professor Charles Phillips (class of 1841), Cornelia Phillips Spencer’s brother, to run the place while it sought a new president. Phillips lived in the Hooper-Caldwell House.

In June 1876, Kemp Plummer Battle was elected president. Battle had grown up in Chapel Hill in a home his father, Judge William Battle (class of 1820), had built for the convenience of his children’s University education. When Kemp Battle, a Raleigh lawyer, moved back to Chapel Hill, he returned to his childhood home after purchasing it from his father.

(No. 5) Battle House in 2015

Battle House, behind Alderman, Kenan and McIver dorms, until recently was a privately owned campus haven for Baptist students. (Photo: Jason D. Smith ’94)

Battle named his home Senlac after the hill on which William the Conqueror defeated King Harold of England in 1066. According to legend, he liked to call himself the “Battle of Senlac Hill.” He retired from the presidency in 1891, taking up a post on the faculty from which he would write the definitive history of the University through the 19th century. He remained at Senlac until his death in 1919.

The Hooper-Caldwell House, which was home to a succession of professors after Swain died, came to a tragic end, burning down on Christmas Day 1886, one day after Professor Thomas Hume had moved his family in. The foundations of the house were uncovered in August 2014 by the University’s Research Laboratories of Archaeology.

It was the first of two presidents’ residences to burn on a Christmas Day.

(No. 6) Horace Williams House in 2015

During the 21-year hiatus between official residences, George Tayloe Winston stayed put in his home on Franklin Street in 1891, when he was elected president. Winston combined two existing houses on the site into what today is one of Chapel Hill’s most elegant addresses. It’s better known for a later owner, philosophy Professor Horace Williams. (Photo: Jason D. Smith ’94)

(No. 7) Julia Graves House, circa 1890

Edwin Alderman moved into this house on the present site of The Carolina Inn at about the time of his inauguration in 1896. Alderman’s wife and infant daughter had recently died, leaving him alone. (“Folder 1110: Chapel Hill: Houses: Graves House, circa 1890: Scan 3,” in the N.C. County Photographic Collection #P0001, N.C. Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC.)

108 years and counting

Battle was succeeded by George Tayloe Winston, a professor of Latin and German, who continued to live in the private residence he had occupied in 1879. This house, on a large lot between East Franklin and East Rosemary streets, is now known as the Horace Williams House, for the renowned philosophy professor who lived there later. The building has an intriguing and irregular form, as Winston took two existing houses on the site (once owned by antebellum Professor Benjamin Hedrick, class of 1851) and combined them to form a single dwelling.

In 1896, Winston left to become president of the University of Texas, and Edwin Anderson Alderman, professor of history and philosophy of education, became the seventh man to hold the title of president. This promotion came to Alderman in a time of grieving. His wife, Emma Graves, had just died, and Alderman had been left childless by the death of his third child in infancy. About the time of his inauguration, Alderman moved from his empty home, the Franklin Street residence now known as the Hooper-Kyser House, to the home of his sister-in-law, Julia Graves, situated where The Carolina Inn stands today. It was while boarding there that he conceived the design for the “modern” Old Well.

(No. 8) Widow Puckett House, circa 1890s

The University owned what was known as the Widow Puckett House on Franklin Street when Alderman left in 1900 to become president of Tulane University. Though the house was never an official president’s residence, Francis Preston Venable lived there; in 1907, halfway through his tenure, he oversaw construction of the house across the street, where presidents of the University and, later, of the Consolidated University and of the UNC System have lived ever since. (“Folder 1123: Chapel Hill: Houses: Puckett House, circa 1890s: Scan 7,” in the N.C. County Photographic Collection #P0001, N.C. Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC)

The Widow Puckett House as it stands today. (New photo: Jason D. Smith ’94)

Frustrated with limited state appropriations, Alderman left UNC in 1900 to become president of Tulane University and later of the University of Virginia. His successor, chemistry Professor Francis Preston Venable, then lived in the University-owned home on Franklin Street now known as the Widow Puckett House.

But Venable, who devoted much of his 14 years in office to the physical improvement of the campus, did not let his term pass without putting an end to the ad hoc style of presidential housing. In 1907, the University built the current President’s House on the western half of the lot formerly occupied by the Hooper-Caldwell House. It was designed by the firm of Frank Milburn, which had designed most of the structures built during Venable’s tenure.

When Venable moved in, finally the president of the University had a permanent home. Edward Kidder Graham (class of 1898), Harry Woodburn Chase, Frank Porter Graham (class of 1909), Gordon Gray ’30, William Friday ’48 (LLB), C.D. Spangler Jr. ’54, Molly Broad, Erskine Bowles ’67 and Thomas Ross ’75 (JD) followed him there.

Isaac Warshauer ’15 is a research assistant in the Research Laboratories of Archaeology. He researched the presidents’ houses as an undergraduate, advised by former School of Government Director John L. Sanders ’50 (’54 JD), who began gathering information on the subject during the University’s Bicentennial.

Timeline of those who have served as chief executive officers of The University of North Carolina, the Consolidated University and the UNC System.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.