Just Put an X Right Here

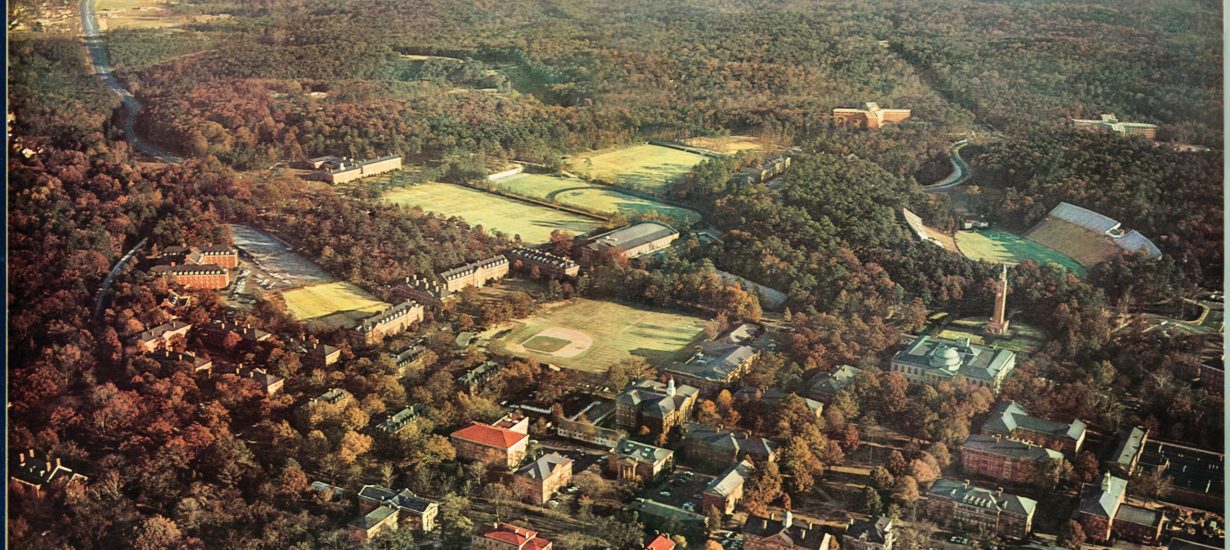

Faced with an enrollment boom and forced to be frugal, Carolina dove headfirst into the forest, and a lifestyle known as South Campus was born.

by David E. Brown ’75

For those whose birth during and just after World War II destined them to be in Chapel Hill in the early 1960s, it seems like college was not just an education but a sociological trial by fire.

The campus as surrogate parent was an idea whose time was almost gone. Attitudes morphed from what’s expected of us to what we demand.

Talk of equal rights for black and white spilled onto the sidewalks and into the streets, and students of color trickled into a traditionally all-white school that had fought to keep it that way.

The N.C. General Assembly, shaken by challenges to the status quo, lashed out at free speech on the campuses.

Women swelled the student body but arrived to find two sets of rules, theirs far more restrictive; men kept an eye on Southeast Asia, and war became to many an unfamiliar source of discontent.

On top of all this, there were a lot more mice in the maze — the student population exploded 165 percent in the 10 years following their fathers’ war, and it would nearly double again between 1955 and 1965. Something had to be done about that, and that something was to put a shovel in the ground out on the far limits of walking distance.

South Campus/The Great Beyond/UNC-Pittsboro was born with the opening in 1962 of Ehringhaus and Craige dorms, and residence life — for those who sought the high-rise adventure and those who couldn’t avoid it — was forever altered. It wasn’t long before those who watched over students’ living conditions wondered whether this all was a mistake.

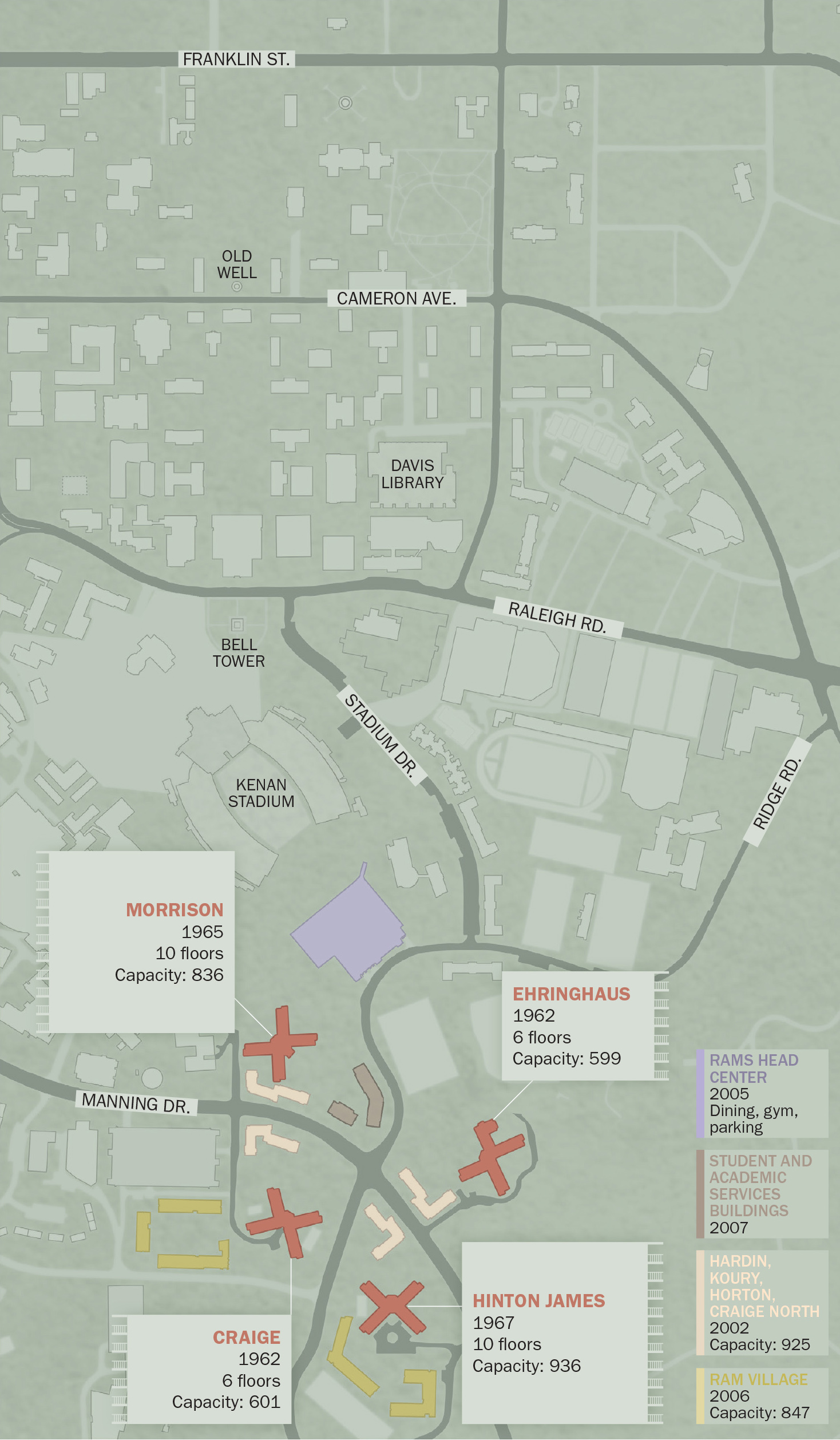

Only in the past 10 years did UNC locate basic student services and a recreation gym near the four original dorms. It built four more South Campus dorms in 2002 and five apartment buildings in 2006. (Map by Jason D. Smith ’94)

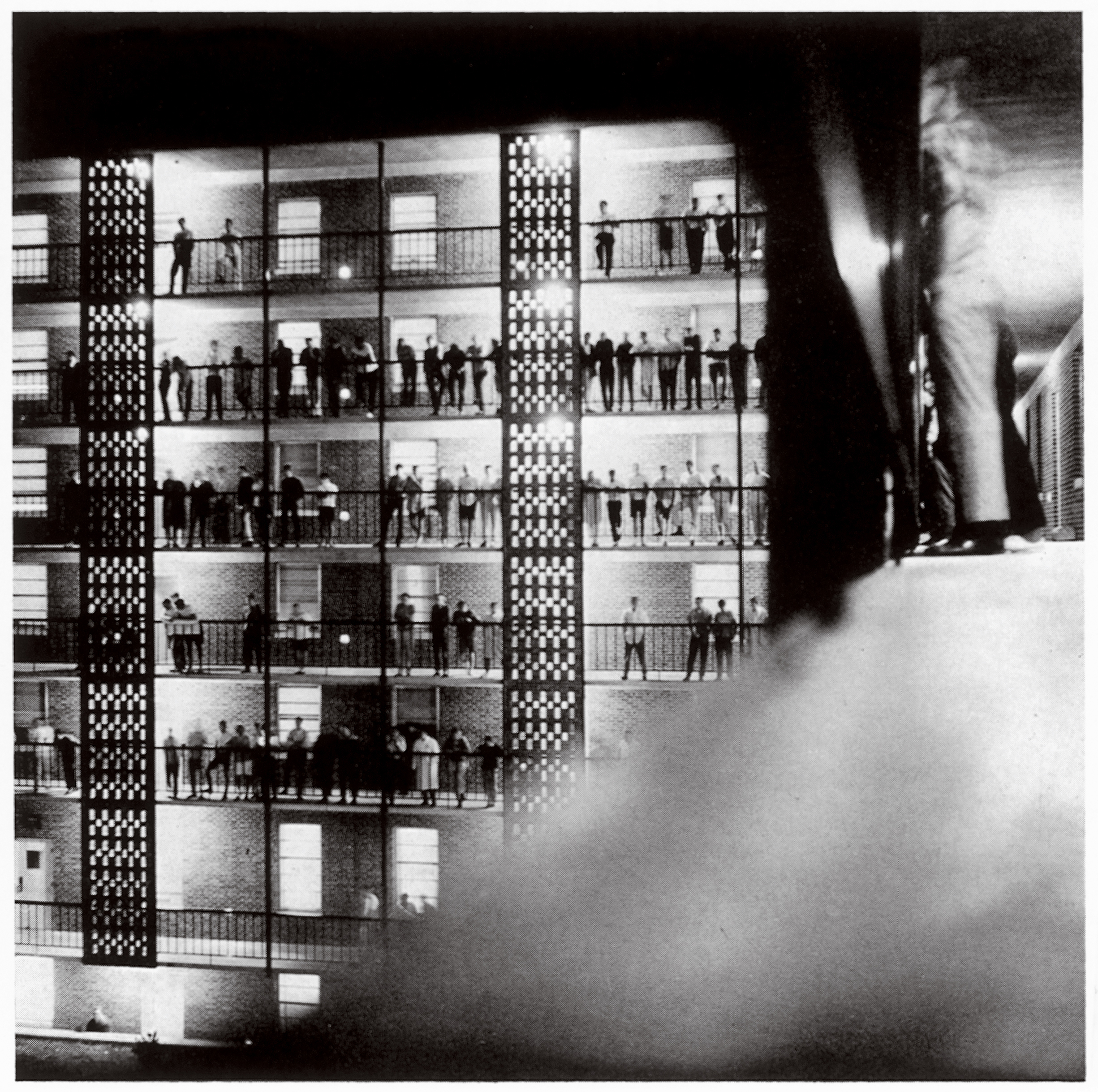

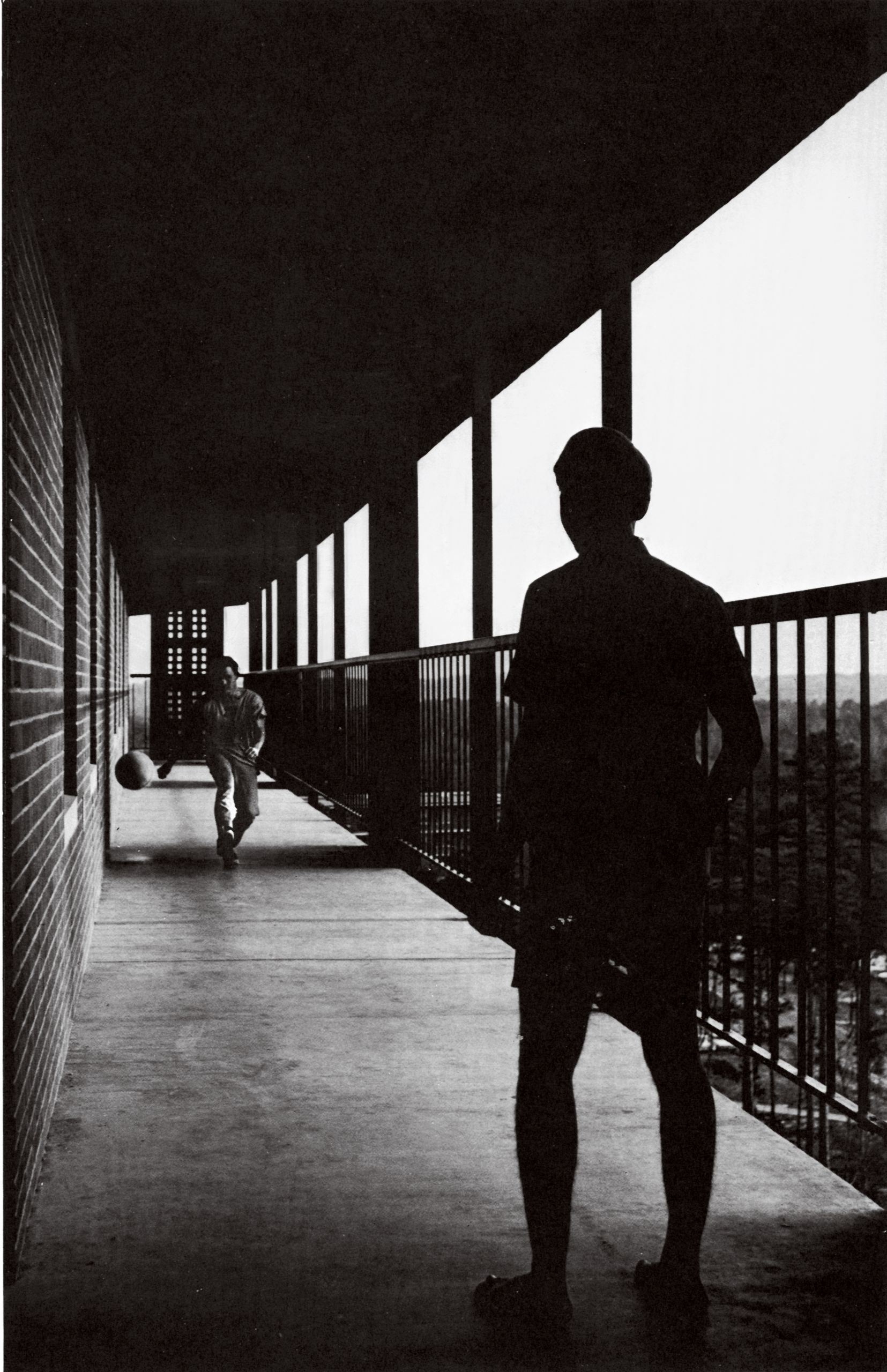

A state-mandated expenditure of less than $4,000 per bed meant few frills for the South Campus high-rises. There were not enough common areas or social rooms; heating costs in Ehringhaus and Craige went through the roof because there were no individual controls; air conditioning was out of the question, and only Morrison has central air even today. (Photo by Jock Lauterer ’67)

In 1965, Dean of Men William Long wrote to Dean of Student Affairs C.O. Cathey ’48 (PhD): “I am convinced that the eight-man suites mitigate against significant community life.”

Long was laying out his vision of the “residential college,” a concept born in the Ivy League and other Northeastern schools in which the university experimented with making dorms centers for organized learning and socialization — such as teaching some classes in the dorms and even placing faculty members in residence there. The idea was to be applied all over the campus, but Long’s assessment was clear: The challenge was different in the eight-person suite arrangement with few and small common areas on South Campus, much different from the “long hall” design of the traditional dorm.

However less than desirable, the high-rise was here to stay. UNC had to have that kind of density to cover enrollment growth (another 66 percent in the decade before 1975) and relieve overcrowding on North Campus. State legislative rules limited spending to less than $4,000 per bed on construction, so there wasn’t much for frills.

But for the men there in the early years, there was something about the isolation that made South Campus living an adventure.

“I would hate to have one of my own men hit with a pop bottle some night, and one of these days one of the cab drivers is going to get real mad and then no telling what will happen.” — Campus Police Chief A.J. Beaumont, after a spate of water-bomb attacks on cab drivers at Ehringhaus. (1964 Yackety Yack)

A cultural change

“You may be looking at the first residents of Morrison dorm.”

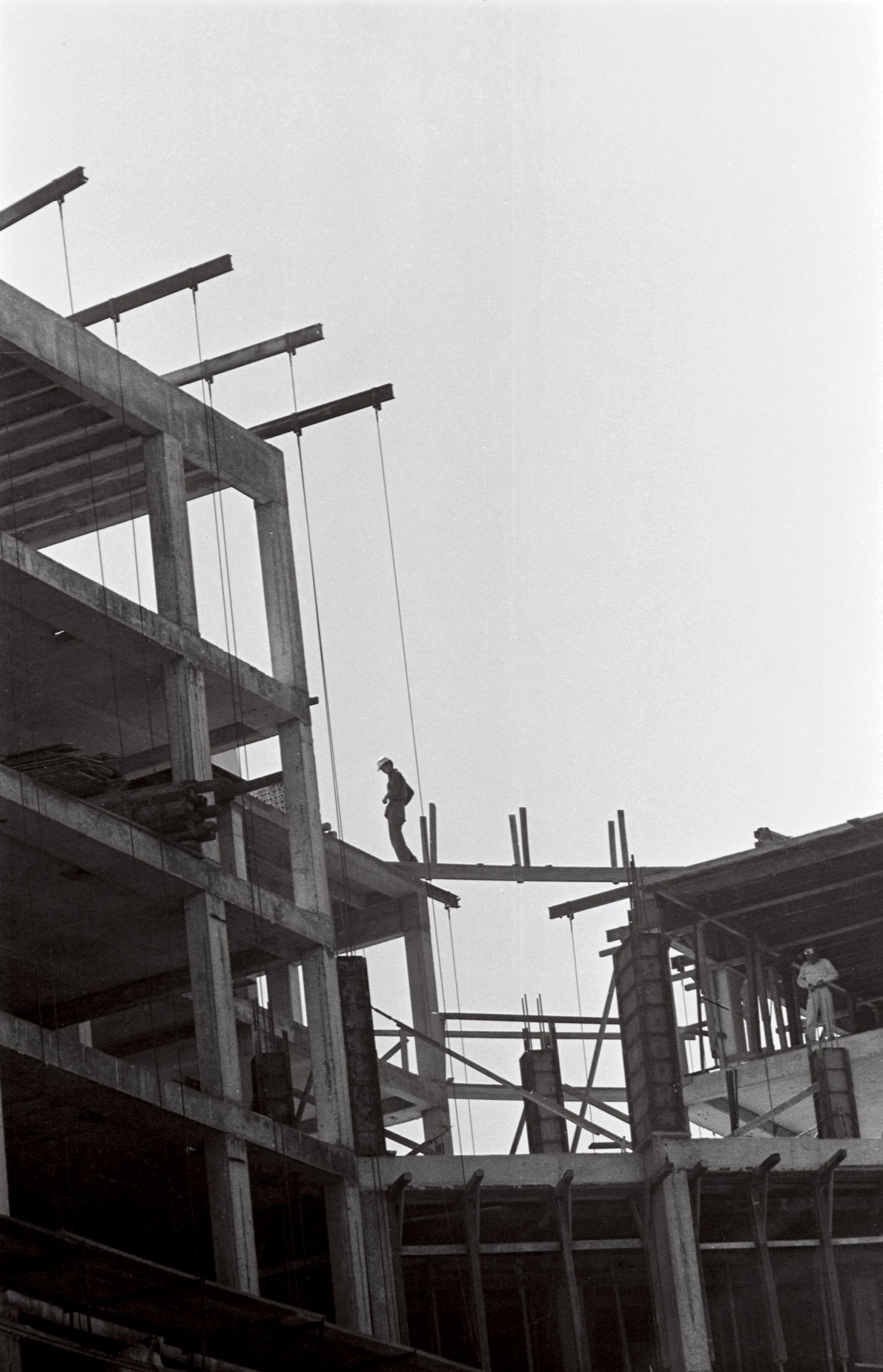

Gene Matthews ’67 (’71 JD) and Marion Redd ’67 are cousins who stuck around the Chapel Hill area. Three years after the six-floor Ehringhaus and Craige had welcomed South Campus’s pioneers, the University upped the ante with the 10-story “Big Mo” in fall 1965. Its assignees were notified in the summer that they should stay home until Sept. 10 because Morrison dorm “might not be finished.”

“I had to be here a week before orientation, to plan a big dance with UNC-G women,” Matthews, assigned to room 913, continued. “The door was open, and I just went in.” The building was missing a few things, like a certificate of occupancy. “They came in with a punch list, and I was in the bathroom. They said, ‘What are you doing here?’ I said, ‘I’m here. I live here.’ ”

A dance with women from UNC- Greensboro would have been a good thing. By then, the dorms that look like giant X’s from the air already had a monastic reputation — except for some graduate students in Craige, women would not move in until the first undergraduate gender-mix experiment in Hinton James, two years after its 1967 opening.

The University was clearing space for women — Cobb was converted for women in 1962 and Winston in 1965 (when Granville East also opened for women), but Carolina was not including them on South Campus.

In spring 1968, The Daily Tar Heel declared: “A whole weekend can be spent on South Campus without once seeing a girl.”

Redd already had spent a year in Ehringhaus. And while hundreds of students — particularly freshmen — over the next few years would see Carolina skip over their North Campus dorm preferences and send them straight to the south, Redd wanted E-haus after a year in Graham, a dorm that “seemed old” and had three men to a room. “There was some buzz for a while about the new place,” he said.

The food was even good. The cafeteria in the Ehringhaus basement had not yet become exclusive to football players, and the South Campus population ate there in the three years before the area got a central dining hall.

In the early years, before land was cleared for Morrison and for Boshamer Stadium, Ehringhaus and Craige sat in the forest, and the sense of isolation was real. Industrious boys climbed the brick latticework; later renovations removed that temptation. Water balloons and small refrigerators found their way from the sixth-floor balconies to the ground by the shortest route possible.

Redd and Matthews are among legions of students who remember the gong wars that served as Morrison’s introduction to its shorter neighbor.

Matthews also was a South Campus veteran when he came to Morrison. He’d lived in Craige — known at the time as Maverick House — which had a well-organized social structure and claimed to be the founder of the first interdormitory governing body. “We went to the Gator Bowl in ’64 [1963, actually]. Some students brought back, I think, a part of the goal post, on which they hung this gong they got from somewhere.

“Some of this gang moved to Morrison the next year. Morrison, with 1,000 boys and nothing to do — there were a lot of rivalries.” And a stolen gong.

“During a shouting contest between the two dorms across Manning Drive, somewhere from the bowels of Morrison you’d hear ‘BONG’ — and it drove the Craige people crazy.”

Craige’s side bragged it had a plan to recover the gong but that the police chief and the dean of men had asked them to back off.

Not long afterward, an elevator opened in Craige and there it was, adorned on one side with “Morrison No. 1” and “Big Mo” on the other. Maverick argued that Mo wasn’t big enough to return it in person. (By 1967, 60 percent of Craige’s population was graduate students, and undergraduate hijinks were moving elsewhere. Craige was all graduate students by 1969.)

The opening of Morrison coincided with a liberalization of women’s dorm visitation rules. Now women could be seen in common areas at certain times, though they had to use “designated elevators only,” and only male students were allowed onto the wings that led to the suites.

“Morrison changed the culture of South Campus,” Matthews said. “They were doing a lot more social things. The social culture changed.”

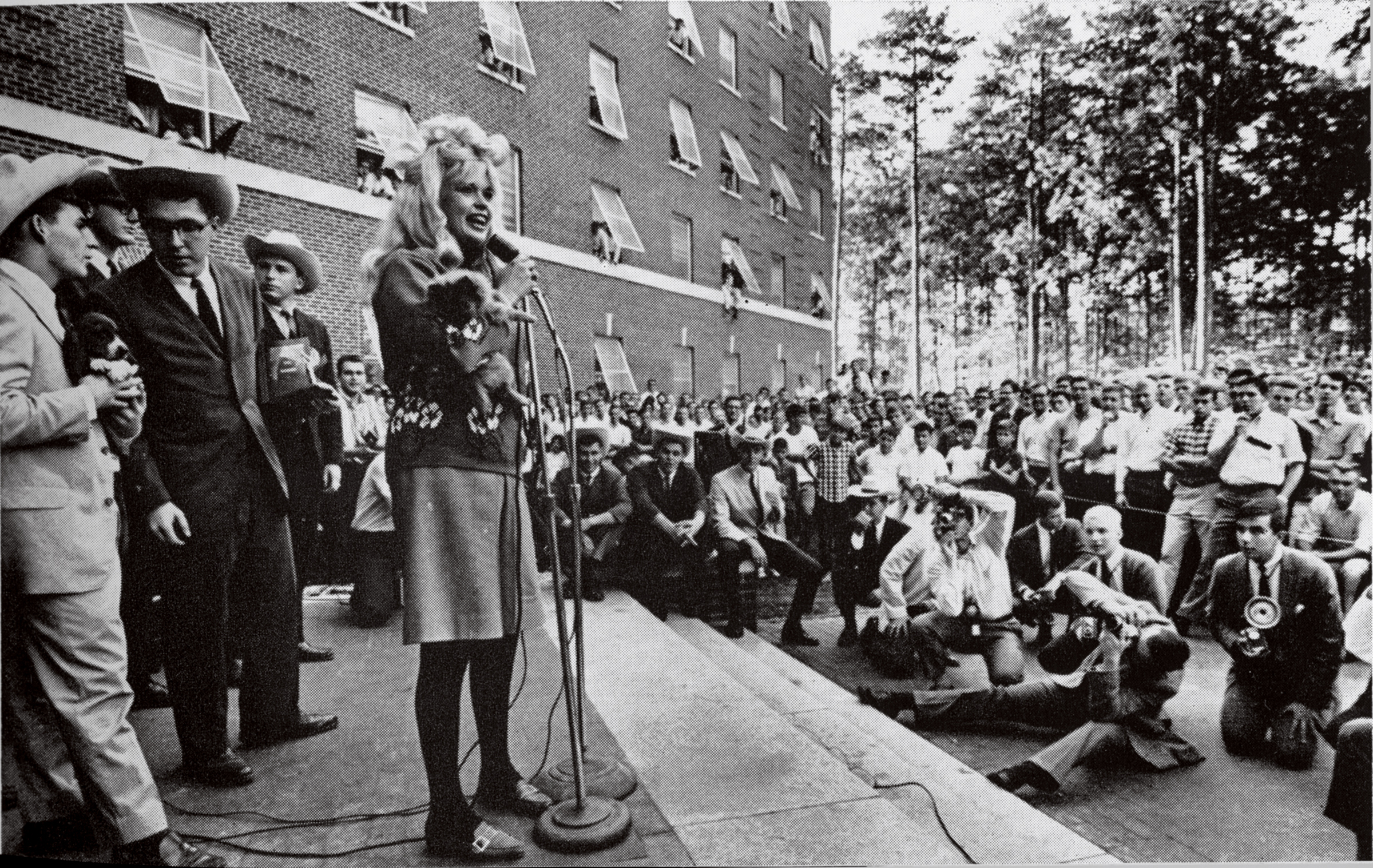

Jayne Mansfield greets the men of Maverick House, a.k.a. Craige, on an October afternoon in 1965. She was there 30 minutes, but that was long enough to dedicate the dorm’s party room. (1965 Yackety Yack)

There was, too, a growing camaraderie. Before Morrison opened, Craige and Ehringhaus residents funneled onto Ridge Road and a raised path that wound behind Avery dorm for the march to class. Morrison came with its own dirt path down into the steep ravine at the east end of Kenan Stadium. In the unusually wet winter of 1966, this became a swamp. The physical plant had dropped pallets of bricks near the dorm, but the work remained undone.

Big Mo residents took the job upon themselves. Somebody put up a sign saying “Lay a brick,” and within a few days there were 5,908 bricks trailing down to the stadium. The physical plant said it had been too wet to do the work. That, the boys thought, was the point.

But not everybody walked. For a brief time, parking on South Campus and in the Bell Tower area was relatively abundant, and those who had cars often commuted. “I don’t think I ever walked to campus,” Matthews said.

There was no mass transit on South Campus before 1968. UNC toyed with the idea of something called “tiger-trains” — 8-mph tractors pulling trailers that could carry 54 souls — but passed on that.

Finally, there is this from The DTH: “About 400 students, professors, townspeople, children and babies waited restlessly. Students leaned out of windows, off balconies and the porch roof. … The gray Bentley pulled a U-Haul trailer whose contents remain a mystery. A throng crushed around.

“After a suspenseful wait the convertible top drew back slowly to reveal a high pile of bleached blonde hair, a white bow.”

In 1965, Jayne Mansfield was the dictionary definition of female sex symbol in America. And one Sunday in October, she detoured from an appearance in Greensboro to come dedicate the social chamber — the Voodoo Room — of Craige dorm.

Somebody apparently had issued a long-shot invitation and hit the jackpot. Jayne passed out autographed pictures and crooned about her latest adventures. Thirty minutes later, she, her husband and her bodyguard bumped over a curb, drove across the lawn and were gone. She appears in the Yackety Yack as the honorary housemother of Maverick House.

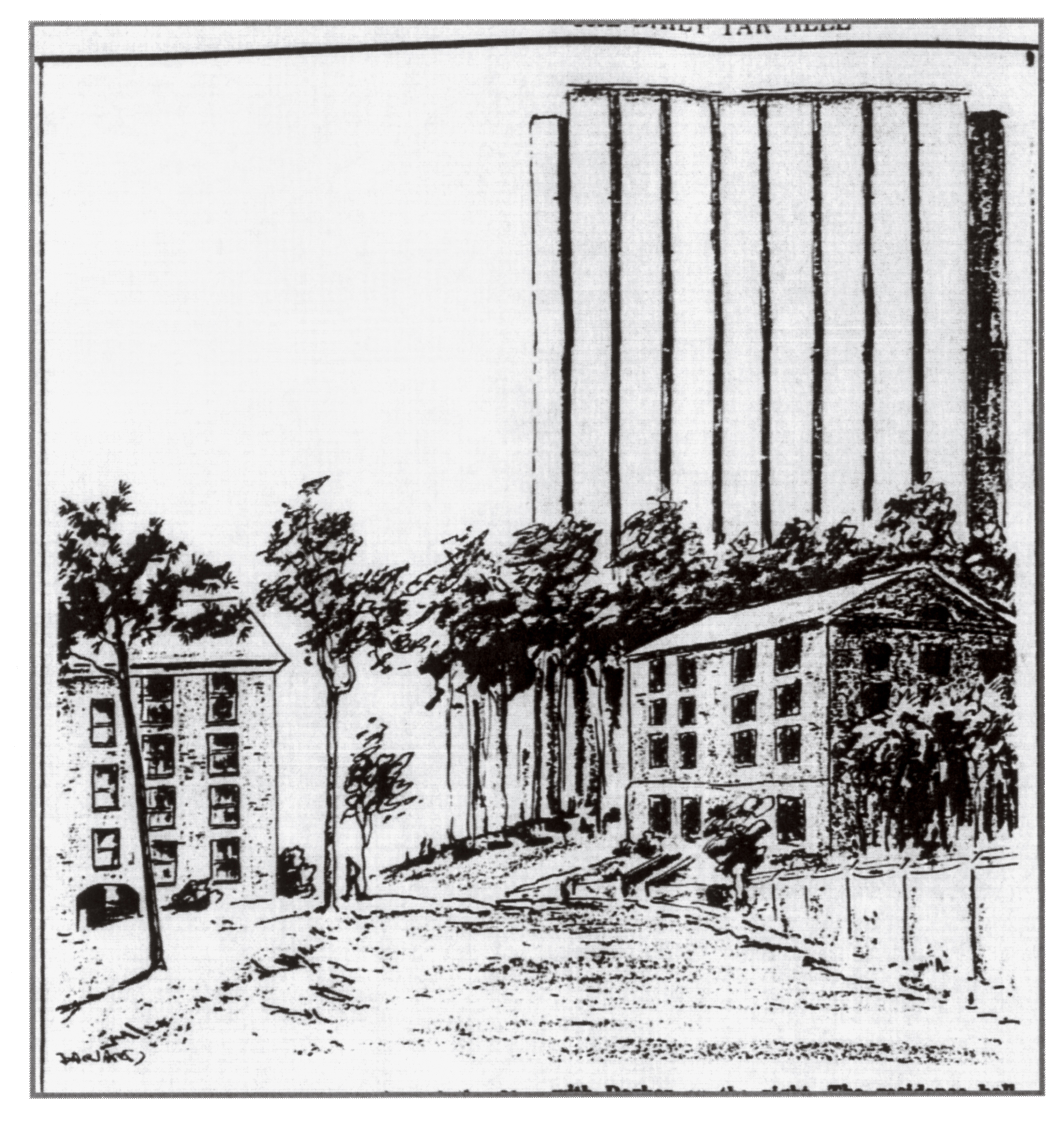

A Daily Tar Heel artist’s rendering of a proposed 21-story dorm that, to our collective relief, never was built. (The Daily Tar Heel/Chip Barnard ’66)

The high-rise is born

Carolina had pushed southward in 1958 when Parker, Teague and Avery opened near Kenan Stadium. They were the first with a suite arrangement (and the widely held myth that their rooms were bigger than those of the high-rises is just that — they’re essentially the same, about 170 square feet).

At the time, the trustees were considering building two dorms on Columbia Street in the vicinity of Victory Village, the temporary post-World War II housing that was still there at the time — beyond the hospital complex and significantly farther south than the existing high-rises.

There was a precedent for going south; construction had started on the 31 buildings of the Odum Village married student housing in 1958.

Soon there was talk of three multi-story dorms. A trustees committee wrote: “Admitting that it was a sharp departure from the traditional type of building construction here, the change was dictated by three major considerations: (1) it made for more economical use of the land and the University is rapidly running out of land, (2) it removed the necessity of cutting so many trees, and (3) the terrain lent itself to this type of development, for each of the three large structures would occupy a knoll, the three forming a semi-circle.”

The Columbia Street site was the first of several that were ruled impractical.

In January 1966 — with the fourth of the existing high-rises, Hinton James, already planned and named — A.S. Waters, the University’s director of construction, told The DTH: “We have a 21-story dorm in design.” That’s twenty-one. “We may have three of them built.”

The first one already was named, for U.S. President James K. Polk (class of 1818), and was to be situated where the George Watts Hill Alumni Center now stands. It would have loomed way above the stadium, right next door. This came in the middle of a debate among student affairs administrators as to whether a high-rise suite system was, while cheap, a bad way for college students to live. But there was another angle: Crowding on North Campus had forced UNC to go three men to a room.

“We’ve found the three-man situation a bad one,” said Dean of Men Long. “Too often it creates a one-man-out situation.”

Chancellor Carlyle Sitterson ’31 was alarmed that each room would be a paltry 140 square feet. But what he said was, find another site — he may have been more concerned about the aesthetic impact on the Parker-Teague-Avery-stadium area.

The next year, the focus shifted to a high-rise for women (in 1967 there still were no undergraduate women on South Campus) to be built between Morrison and the nurses’s dorm at the hospital. This eventually was scrapped, too, but the planning for it highlighted the argument about the high-rise design.

Katherine Carmichael, the venerable dean of women, told student affairs Dean Cathey, “I don’t want another Craige or Ehringhaus for women.” She wanted the long-hall scheme because it fostered more social interaction. (Carmichael also wanted the new high-rise to be “slanted” to capture breezes, since air conditioning was unaffordable, and to shoehorn four women’s dorms onto the North Campus men’s upper quad.)

You have to make imaginative use of space 70 feet up in the air. The eight-person suites are cozy. Morrison, the only one to have a major renovation, now has six-person suites. (1967 Yackety Yack)

Did we make a mistake?

A staff member of the American Council on Education who toured South Campus in 1968 — when all four high-rises were up and running (as was the then-private Granville Towers, though it employed the long-hall design) — said, “I’m impressed by how sterile those buildings are.” He saw in their design an apparent effort to “improve the alienation and desocialization of the students.”

UNC’s building planning director, A.L. Branch, had recognized just after Craige and Ehringhaus opened that the social and recreation facilities were all on the lower floors and that the quality of life seemed to go down as one went farther out the buildings’ wings from the “central core.” The taller Morrison, then in the planning, “will just aggravate these things,” he said.

Then came a confirmation: The report on the 1963-64 academic year showed the grade-point averages for Craige and Ehringhaus residents were, on average, lower than those in other dorms. The two also ranked high in “damage done to the residence halls” and “very low in intramural participation.”

However much fun the boys might have been having down south, student affairs was worried.

The administration put a lot of its eggs in the “residential college” basket. In December 1964, Long set out his vision for residential colleges.

“Living as we do in a specialized society that numbers about 16,000 [total campus population], each of us can easily feel somewhat lost. This is particularly true of the student who often has the impression that he is little more than a few holes punched in an IBM card.”

Chancellor Paul Sharp read Long’s report and concurred. Soon the concept would be in place all over the campus, but it was believed to be particularly important to the isolated South Campus — each of the four dorms there was a separate college.

The idea was to dampen the notion of the dorm as just four walls, a bed, a desk and a closet. It promoted tutoring programs and on-site advising, organized social functions, extracurricular academic programs and governance, and intramural athletics. Some colleges had newspapers, even their own radio stations.

By 1967, Morrison and two other colleges were experimenting with having some classes taught in the dorms. A year later, UNC scheduled 21 sections of English and modern civilization in the colleges and arranged for eight faculty fellows to have offices in the South Campus dorms. Later came attempts to have young faculty members living among the students.

The University planned to put a library in Chase Hall in 1966. That never happened.

Speaking specifically of South Campus, Fred Schroeder, who was assistant dean of men, said: “That was an attempt to bring about more personalization and community-ization in those very large buildings. There was a need for a much more student-friendly experience.” Plus, he said, “we were in the middle of a large social and political upheaval.”

“The isolation was twofold. It was the distance from classrooms. A secondary part of it was the sense of isolation from suite to suite. I spent a lot of time dealing with student issues on South Campus. If there was a problem going on in one suite, I’d say, ‘What’s going on in the next suite?’ They’d say, ‘We don’t know the guys in the next suite.’

“That was different from the long-hall communal living on North Campus.”

‘We should have protested’

A bond referendum in 1961 would have provided for a cafeteria on South Campus; it was defeated, and a lot of alumni would just as soon they’d left it at that, considering what happened in 1965.

From The DTH: “A colorful decor, sleek contemporary design and an ultra-efficient, fast serving method will mark the Harry W. Chase Cafeteria as one of the nation’s best when it opens here in September. The kitchen floors are even marble, it’s more economical.”

From Dr. Blane Yelton ’67 (’71 MD): “It’s a pretty building. It’s a shame you can’t eat buildings.”

“The food was Chase, so that was a downside,” Gene Matthews said. “We should have protested Chase.”

Yet the lines were long every evening, perhaps the ultimate testimony to the isolation of South Campus.

The Chase problem never has been put more succinctly than in the words of its then-new manager, James Carpenter, in February 1967: “I want to get better and faster employees as soon as they can be recruited. But I’ve had the job only a couple of weeks and quite a bit has happened since then. I’ve really had my hands full with this serving size thing and the ‘C’ health rating.”

Can’t live without them

I checked into 530 Morrison in August 1971. Simultaneously, women were moving into the building for the first time.

First weekend of the semester, I went home and bought a bicycle.

I got the worst of Chase; I didn’t even have a meal plan that bound me there, but all the friends I wanted to eat with did, so.

I participated in the disabling of elevators in Ehringhaus, to the deep chagrin of people who appeared to be football players.

I remember the names of most of my suitemates, one of whom became president of my senior class. I can’t name a single other person on that floor. I went north after one semester.

In the winter of 1969, Chancellor Sitterson had approved Project Hinton, and 60 women and 90 men began living on the same top two floors of Hinton James. “Now, for the first time … South Campus males will be able to interact with females on a normal basis,” The DTH reported, “informally, and not as if they were strange creatures, which is the case when they are separated from them by a mile.”

For many years, South Campus residents trekked not only to class but to the gym, the bookstore, the registrar, the aid office, the advisers. On its 40th anniversary, Chase Hall went to the wrecking ball, and a new dining hall, and gym, opened nearby. Two years later, the Chase site was filled with a building that houses the basic nonacademic services in what is now the dominant campus residential village.

Fare-free buses now seem to run one right after the other.

Almost 5,000 students are living in the high-rises, four low-rises built in 2002 and five apartment buildings added in 2006. The four new dorms were designed, in part, to shield Ehringhaus, Craige, Morrison and Hinton James from view from the street. UNC would have preferred to tear them down but decided they were irreplaceable.

The University recently drew up another South Campus dorm on Ridge Road across from Ehringhaus but canceled the plans last year because construction costs would not have been recoverable in room rent and because a renewed interest in off-campus living had reduced the need.

Odum Village, no longer able to meet fire codes, closed this spring.

David E. Brown ’75 is senior associate editor of the Review.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.