Kruse-in’ for a Bruisin’

Posted on Nov. 11, 2019

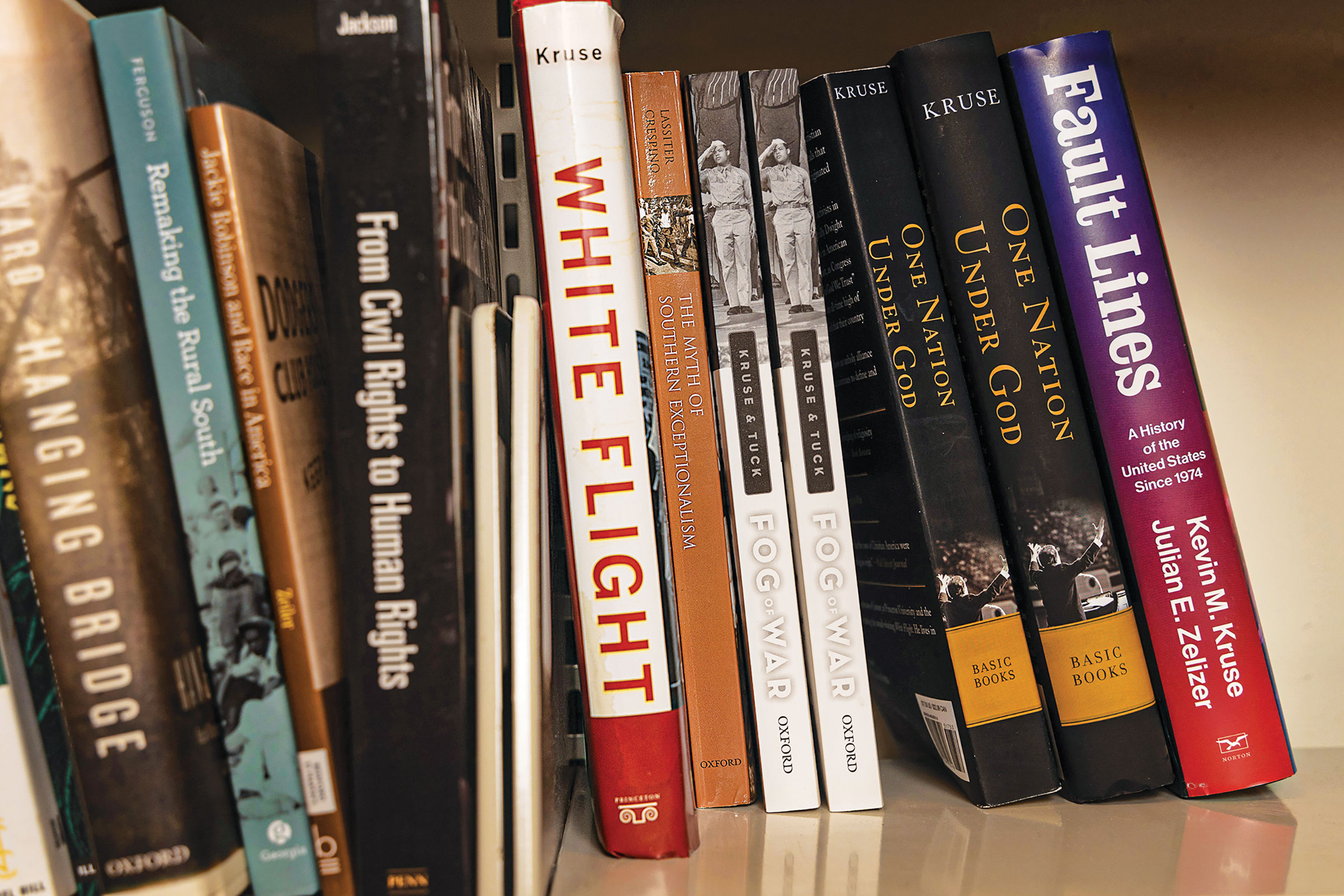

Kevin Kruse ’94 is widely published as a book author, in periodicals and on social media, achieved, he says, by “fumbling my way through” to find what makes him happy. (Photo by Ricardo Barros)

Want to debate history, politics or scholarship? Kevin Kruse ’94 is happy to tweet you. And he’s good for a little rough stuff, if need be.

by Eric Johnson ’08

If journalists write the first draft of history, people like Kevin Kruse ’94 write the second.

The Princeton professor has earned unusual attention outside of academia by turning modern history into a political livewire — tackling issues of race in suburbia, the rise of religious conservatism in American politics and the deepening cultural divisions that roil our public life.

Drawn to controversy and willing to do battle in the modern arena of social media and online news, Kruse is pioneering a model of historical scholarship that looks very different from the staid, slow-burning controversies that used to liven up the faculty lounge.

In the first few weeks of the fall semester, he contributed a piece to The New York Times Magazine on racism and urban planning; spoke about the history of Southern politics at the Decatur Book Festival in Atlanta; announced a visit to Chapel Hill to promote Southern Cultures’ politics issue; co-authored a piece for The Atlantic on the election of Richard Nixon and the emergence of the Republicans’ “Southern strategy”; and kept up a steady barrage of Twitter commentary that takes aim at the Trump administration, lazy media coverage and commentators who ignore or distort the historical record.

“What I like about Twitter is that it’s a conversation. It let me have a conversation with people I’ve long admired. It wasn’t planned or cynical, but I think that really helped it take off.”

– Kevin Kruse ’94

Which is all on top of his day job as a tenured member of Princeton’s history department. “I got into this profession to be happy and do what I want to do,” Kruse said. “I’ve just been kind of fumbling my way through it, trying to figure this out.”

To hear him tell it, fumbling and figuring things out explains his runaway success as a Twitter pundit and popular writer. There was no grand plan to become the go-to source for political editors, liberal commentators and online activists looking for snappy historical context.

Like a lot of people, Kruse was drawn to Twitter as a way of connecting to writers and semi-famous political minds. People who normally would seem out of reach become weirdly accessible in the chaotic world of retweets and direct messages. Kruse found he could jump right into a back-and-forth with someone like Ari Berman, a widely read contributor to The Nation and Mother Jones who shares Kruse’s interest in civil rights history.

“What I like about Twitter is that it’s a conversation,” Kruse said. “It let me have a conversation with people I’ve long admired. It wasn’t planned or cynical, but I think that really helped it take off.”

Twitter also is a medium that rewards controversy, and Kruse is happy to court it. He has an ongoing flame war with Dinesh D’Souza, a rightwing firebrand who Kruse regularly accuses of malicious ignorance. “D’Souza looks to history for validation of his childish worldview — My Team Good! Your Team Bad! — cherry-picking evidence that supports it and ignoring everything that contradicts it,” Kruse tweeted in February. “That’s not how actual scholars handle American history.”

That observation came as part of a long thread on Nazism, the evolution of American political parties, and the intellectual habits of real historians versus “dress-up doctorates” (Kruse’s description) like D’Souza. Those long, discursive threads — dense with links, reading suggestions and call-outs to other scholars — have become a Kruse specialty.

The obscure figures he's referencing here are Trent Lott and Jesse Helms. https://t.co/b1UyUYw3Nk

— Kevin M. Kruse (@KevinMKruse) July 31, 2018

In a profile last December, The Chronicle of Higher Education dubbed Kruse “History’s attack dog,” pointing to his hundreds of thousands of online fans and his penchant for landing viral blows in noisy online debates. “In this era of political crisis, people turn to social media, where pundits are waiting to reassure them that history is on their side,” the Chronicle wrote. “But most of them haven’t studied history as carefully as Kruse.”

Living the dream

He may be history’s attack dog online, but Kruse is all charm in person. In his quiet and cluttered Princeton office, his warmth, rapid-fire pace and sheer intensity seems out of place inside the placid gray stone of Dickinson Hall. Crayon drawings from his two young kids are pinned above his computer, and old VHS cassettes of History Channel documentaries slump at the end of an overfilled bookshelf.

Winding up here was no accident. After growing up in Nashville, he chose to attend UNC over Duke in part because Carolina had a more highly rated history department. And because it was cheaper.

“In high school, I was really sold on Duke. I wanted to go really badly,” Kruse said. But a visit to each campus helped change his mind. “Duke was Duke, and Carolina was … well, it was Carolina! It was a lot more fun, and I wanted that.”

Twenty-five years after graduating, Kruse can still reel off comments and advice he received from UNC professors. He remembers notes that the historians Bill Leuchtenburg and Harry Watson made on the draft of his senior thesis, which was about the North Carolina reaction to Harry Truman’s civil rights program. “It was not a good thesis,” Kruse laughed. “But God bless them, they stuck with me on this. And things turned out all right, I guess.”

(Photo by Ricardo Barros)

They certainly have so far. Kruse’s first book, White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism, was honored by the Southern Historical Association and won attention well beyond the academic world. “Kruse’s research ultimately led him to some provocative conclusions,” wrote Smithsonian Magazine. “He argued that urban whites ultimately thwarted desegregation not by opposing it but by escaping it — that they essentially ceded contested turf (neighborhoods, schools, parks, pools) and trekked to greener pastures.”

That book set a pattern of provocative, well-researched insight about our current politics. One Nation Under God, published in 2015, contends that the idea of America as a fundamentally Christian nation originated not in the founding era but during a period of historical revisionism that began in the 1930s and continues to this day. “The rites of our public religion originated not in a spiritual crisis, but rather in the political and economic turmoil of the Great Depression,” Kruse wrote. “This history reminds us that our public religion is, in large measure, an invention of the modern era.”

In tracing the history of phrases like “In God We Trust” and “God Bless America,” Kruse finds an alliance of business leaders and conservative religious figures who united to oppose government intervention. That faith-based rhetoric is now so common that it’s used by presidents and political leaders of both major parties. In a 2015 interview with NPR’s Terry Gross, he noted that both George W. Bush and Barack Obama relied on faith-based language to argue for greater tolerance.

“This fusion of faith and freedom, of piety and patriotism, is alive and well,” he told Gross. “If it’s used to bring Americans together, I think, in a genuine spirit, I think it works well. But I think if it’s used to advance a partisan agenda, I think it quickly becomes polarizing.”

Earlier this year, Kruse and his Princeton colleague Julian Zelizer published Fault Lines: A History of the United States Since 1974. Not many political science tomes earn their authors an interview in Vogue, but it turns out the readers of the nation’s premier fashion magazine are hungry for historical insight. Kruse and Zelizer “survey the modern political landscape like geologists looking for the ancient faults,” Vogue reported. Like Kruse’s online commentary, Fault Lines is jaunty. It bounces among urban design, technology investment and the game show Who Wants to Be a Millionaire in the span of a few pages, trying to explain the cultural origins of our political stalemate.

“To spend a career teaching and writing and talking about this stuff, that was the dream,” Kruse said. “That’s the reward.”

Art of the Twitter brawl

There are days when the reward seems to come with a lot of punishment. For choosing to tackle controversial subjects and wade into the fray, Kruse gets hate mail. He gets scorn from some colleagues who find all of the publicity unbecoming. And he is perpetually overwhelmed with the balance between workaday commitments — family, teaching, research — and the chance to take on new projects.

(GAA illustration by Haley Hodges)

But he also really, unabashedly loves it. “I get to write about whatever I want!” he practically shouts, manifestly giddy at the thought. “The only real limit on that is whatever I can fit on my plate.”

Kruse’s argument for all of the public engagement is simple and compelling: If well-informed historians don’t join the fray, they leave the field wide open for uninformed hacks.

“There are definitely people who see this as a waste of time. There is an attitude out there that it’s not the place of an academic to get into these day-to-day political controversies. But I think the facts actually matter. I think it’s not a small thing to spend time putting these facts in the public sphere, especially in an era of ‘fake news.’ ”

Much of his Twitter engagement and public writing simply points people back to primary sources — exactly the kind of direction he gives to his Princeton students. In that sense, a Twitter brawl on the merits of presidential impeachment is just another opportunity for teaching history. Point back to some polling data from the Nixon era, cite foundational debates about high crimes and misdemeanors, and hope that tiny injection of academic rigor might nudge the debate in a better direction.

There are days when the reward seems to come with a lot of punishment. For choosing to tackle controversial subjects and wade into the fray, Kruse gets hate mail. He gets scorn from some colleagues who find all of the publicity unbecoming. And he is perpetually overwhelmed with the balance between workaday commitments — family, teaching, research — and the chance to take on new projects.

“The stuff I do on Twitter, there’s nothing special about that. Hell, an undergrad history major could do a lot of the basic stuff I do. But it’s got to be said again.”

He has no illusions that diligent footnoting will sway the fiercest partisans. “Dinesh D’Souza either ignores or insults me, and that’s fine,” Kruse said. But rebutting the author of The Big Lie: Exposing the Nazi Roots of the American Left and the Roots of Obama’s Rage matters to Kruse because bad history leads to bad politics. “For far too long, the reaction of academics was to look at books like that as a joke. Engaging it is beneath us. [D’Souza’s] books aren’t getting reviewed in The American Historical Review, so who cares, right? That was the attitude.”

Meanwhile, D’Souza’s books outsell anything and everything in The American Historical Review. Time for the professors to get in the game and talk to people where they are, which is mostly online.

But even Kruse has his limits. Challenged by D’Souza and his allies to hold a debate on Princeton’s campus — a challenge issued on Twitter, of course — Kruse got into a sniping back-and-forth about the limits of scholarly engagement. To one Twitter user who suggested inviting D’Souza to campus, Kruse retorted that “history professors here don’t ‘debate’ facts on stage with publicity-hungry con men.” And later in the exchange, “If you think I’m going to welcome someone like that — someone who also promoted birtherism, mocked Parkland victims, retweeted #BurnTheJews and pled out to a felony — to Princeton as my honored guest, then you’re absolutely insane.”

In other words, the rules of Twitter engagement don’t necessarily translate into the offline world. The pugnacious style that trends so well on social media falls flat on the stately grounds of Princeton proper, and that’s a tension Kruse has to navigate in his daily work.

One of his most influential teachers at UNC was Leuchtenburg, the thesis adviser whose comments Kruse still can remember. A widely respected scholar of modern presidential history, Leuchtenburg is best known for his work on Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal. He also was a master at blending scholarly insight with lively narrative, making history resonant in the present day. It’s part of what earned him a reputation for great teaching at Carolina and made many of his books popular with a general audience.

“It was amazing,” Kruse recalled. “It seemed like he knew everyone and everything. These lectures would just roll out of him, and they were 50 minutes to the second. He had this spellbinding story style that would just draw you in.”

Kruse has done his best to adopt that style in the classroom, where he opens and closes each session of his American politics class with a song from the era being studied. He might take the stage with Mavis Staples blasting through the auditorium and close with a riff from Creedence Clearwater. Keeping the lectures moving along is a habit he traces back to those Leuchtenburg talks.

But in terms of public presence, it’s clear that times have changed. Leuchtenburg rose to prominence in an era when popular engagement meant appearing in PBS documentaries and having an in-depth chat on Bill Friday’s North Carolina People television show. Kruse’s world, where you can tap out history-themed zingers on a cell phone and watch the news cycle erupt, has a different velocity.

“It’s weird to live in this universe where I can type something while I’m walking across a parking lot, in what feels like this private moment, and later that night I see it on MSNBC.”

The John Doar project

Despite his prolific online presence, the age-old disciplines of research and writing continue to guide Kruse’s life. “On a regular day, I don’t really leave a quarter-mile radius,” he said, motioning beyond the beautiful picture windows behind his desk. “A lot of it is spent in isolation here in my office, or teaching and meeting with students.”

He won’t be in the classroom for the 2019-20 academic year because he’s on research leave, delving into the newly opened papers of the quiet civil rights crusader John Doar. As assistant attorney general for the Justice Department’s civil rights division, Doar helped lead the charge for racial integration. He was present at some of the most high-profile moments of the era, traveling to hot spots across the American South as protests raged and the federal government worked to enforce basic rights for black citizens.

Kruse is on research leave, delving into the newly opened papers of the quiet civil rights crusader John Doar, who was on the front lines of the movement. (Photo by Ricardo Barros)

“I want to use his story to rethink how we look at the civil rights movement,” Kruse said. “To think about the relationship between federal, local and state politics.”

With the support of Doar’s family, Kruse has exclusive rights to the archives for the next year — 212 boxes full of memos, letters, photographs and other raw material that cover some of the most iconic moments in modern American history. “The drama, the details that have come out of these archives already are just off the charts,” Kruse said.

That’s because Doar was no ordinary bureaucrat, passing time in a D.C. office. He traveled all over the South, intervening in tense standoffs and negotiating the federal government’s increasingly assertive role in fighting segregation. Doar wasn’t just present when James Meredith became the first black student to attend the University of Mississippi; he stayed in Meredith’s dorm room as riots raged and federal marshals battled to quell the violence. Doar stood between protesters and police in downtown Jackson, Miss., to defuse an explosive standoff. He appeared before all-white juries in the Deep South and won convictions for the murder of civil rights workers. He saw colleagues violently beaten for bringing federal authority into places deeply resistant to change.

“Doar’s story has such an incredible natural narrative to it,” Kruse said. “I would have to really bomb it to screw up this story.”

Success, for Kruse, will mean using the natural pull of Doar’s biography to illuminate deep questions of how federal law brought about social change.

Success, for Kruse, will mean using the natural pull of Doar’s biography to illuminate deep questions of how federal law brought about social change. How did the civil rights movement create structural changes in the relationship between states and federal authorities? How did that era shape the political evolution of the South and the country, with Southern Democrats fleeing en masse to the Republican Party and black voters emerging as a reliably Democratic base?

“It’s about letting the inherent drama do the work. Rather than making arcane points about federalism and law enforcement, you tell the stories, the human stories,” Kruse said.

Especially in a new era of intense political protests and hard questions about race in America and the relationship between activists and governing institutions, the story of the Justice Department lawyer who helped prompt the Selma-to-Montgomery march seems likely to resonate. Uncovering the on-the-ground details of Doar’s fight for progress can make our own moment a little easier to understand.

“I’m in the early stages of the project where I’m all optimism, finding new things in the archives and going off in new directions,” Kruse said. “But I feel like I’ve been prepping for this book my whole career.”

For Kruse, this is the true upside of the intellectual freedom and nerdy fan base he has earned at Princeton. It gives him the chance to spend long hours in the archives, emerging with new drafts of history to share. Whether that comes as a scholarly monograph, an undergraduate lecture or a well-aimed Tweet, it’s all part of the mission.

“I knew I wanted to teach — that’s where it all started,” Kruse said of his career. “And that’s still what it’s all about.”

Eric Johnson ’08 is a writer based in Chapel Hill who previously worked in UNC’s Office of Scholarships and Student Aid and with the UNC System office. He now works for the College Board.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.