Nobody Asked Me That Before

Posted on Nov. 10, 2017

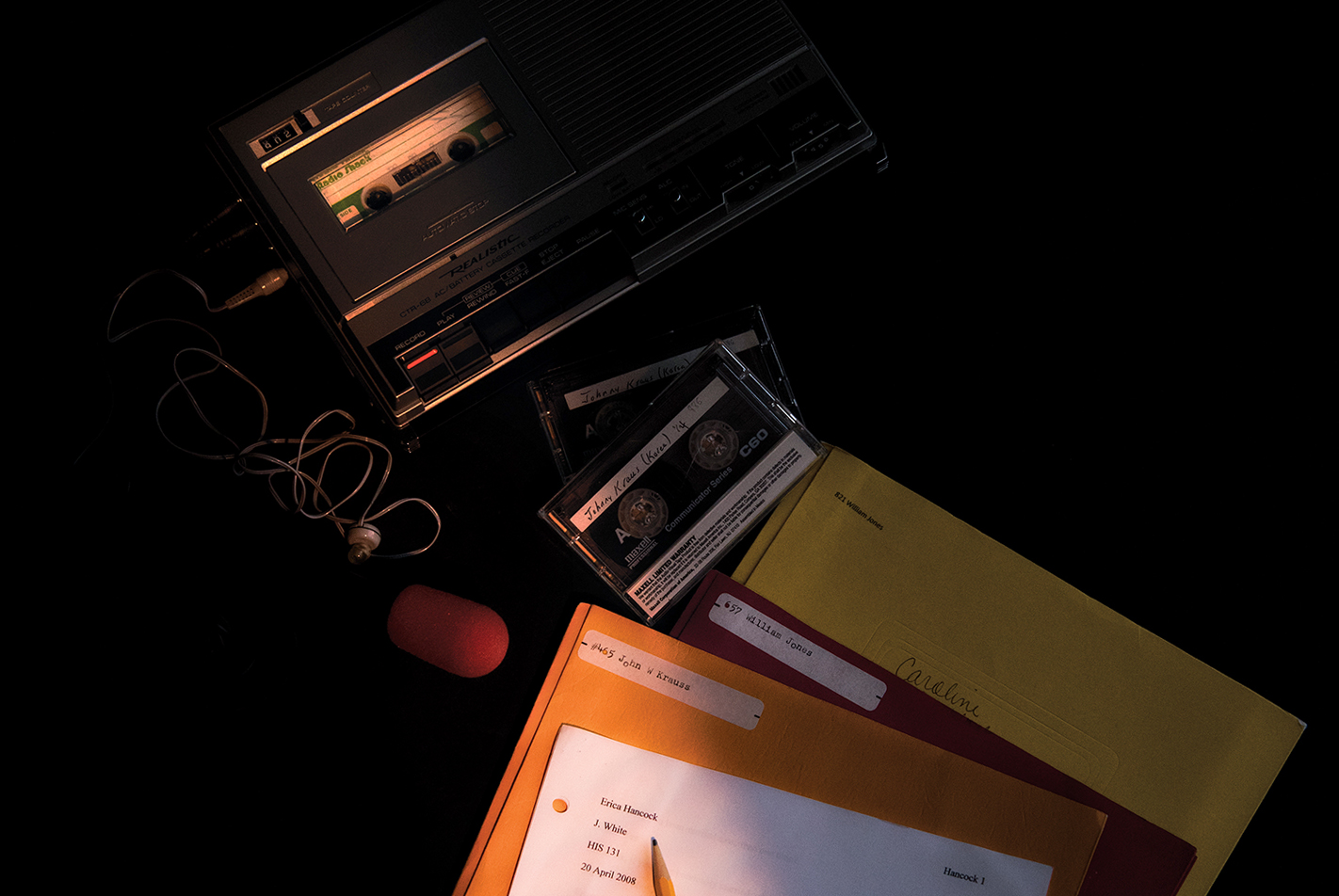

Jim White ’71 had his students tape veterans from every major conflict since the start of the 20th century. (Photo by Grant Halverson ’93)

There is a time limit on harvesting history from primary sources, and trained preservationists can’t get to it all. Ordinary historians — such as students sent out to listen to the stories of war veterans, and vets themselves who deeply understand the value — continue to enrich the Southern Historical Collection.

by David E. Brown ’75

Jim White ’71 came by his passion for history naturally. His people lived on Portsmouth Island, the wildest and most remote outpost within North Carolina’s borders, from 1822 until 1933.

Some of them were blockade runners during the Civil War.

Jim White’s students taped vets from every major conflict since the start of the 20th century, including three from World War I. The Library of Congress wanted the material; so did the National World War II Museum. (Photo by Grant Halverson ’93)

White’s high school students over on the mainland in Pamlico County — well, you know how at that age history can seem a little bit stale.

It was the early 1990s, and “I got tired of my students copying each other’s papers,” he said. “I said, ‘I’ll come up with something they can’t copy.’ ”

He began dispatching his students to interview war veterans. They weren’t that hard to find in retiree-rich Pamlico and Craven counties.

“The kids cried because they didn’t want to do it. They hated it. When they got through doing it and turned their papers in, I said, ‘Now what did you think about the project?’ They said, ‘It was the best thing I’ve ever done in my life. Do it again.’ ”

William Jones volunteered and enlisted before the United States entered World War II. He was 16. He found himself at Pearl Harbor – he served in one of the few roles available to African-Americans, as a steward – on Dec. 7, 1941.

“I had been in town that night and…I came back at about 1 o’clock and at about 7 that morning the bombs and the machine guns started shooting – where we were standing there.” He and his roommates were in the barracks. One of them had just stood up from his bunk. “Machine guns came down where he’d been there and just cut that bed right apart.”

Jones flew out of the room and went to an airplane hangar, which was considered one of the safer places to be.

Before the war ended he had risen to captain steward, served on three ships and was chief steward to Adm. Chester Nimitz, who directed the major Pacific naval battles of the war.

William Jones interview (17 minutes)

After White left Chapel Hill with history and political science degrees, he had dabbled in the now-popular discipline of oral history, taking a tape recorder to lunches with Grandmother Lucy and Aunt Nina at just about the time the last permanent inhabitants were abandoning Portsmouth.

“I would sit down with Aunt Nina, have a glass of sherry, and we would talk and she would tell me all those stories on tape,” White recalled. “I got, I guess, 10 or 12 hours of her on tape.”

As the last of the Portsmouth population aged and grew tired of fending for themselves in hurricanes, the U.S. National Park Service started interviewing them. The Park Service found out about White and copied his tapes.

“This fed on my interest in oral history. I didn’t do anything with it for years. I taught school, became a principal, served 14 years, got tired of the politics and decided I’m going back to the classroom. I wanted to do something different and creative.”

When he told his students to go and ask questions for themselves, they quickly were fascinated with “these old gentlemen.” But White soon realized they had no idea what to ask. He worked with them to develop questions; they talked about how to avoid yes-and-no answers. The students learned to ask open-ended questions, to pry stories.

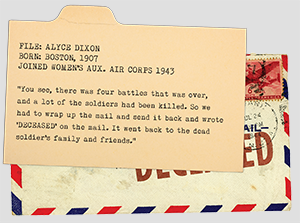

Alyce Dixon was interviewed in either a Veterans Administration Hospital or a nursing home when she was 99. Born in Boston in 1907, she studied one year at Howard University and one at American University, married in 1930 and joined the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps in 1943.

“I was one of the first women in the Army to be called WAAC.”

In Birmingham, England, “We rerouted the mail and sent it back to the States. … You see, there was four battles that was over, and a lot of the soldiers had been killed. So we had to wrap up the mail and send it back and wrote ‘DECEASED’ on the mail. It went back to the dead soldier’s family and friends.”

Whenever Dixon got a pass, she’d try to see some of Europe: Belgium, the Black Forest, Venice, Rome.

“In France, I went down the Seine River, and I saw a lot of youngsters, children, little girls carrying their baby sisters and all. And down the Seine there were bodies floating down the river. And I met this little girl who was 12 years old with her baby sister in her arms and I tried to find out what had happened, so she told me her mother and father were gone, and this was her baby sister she was trying to hold onto, and I felt so sorry for her. And we became friends, and I gave her some of my clothes — they had lost everything — and she went and bought some perfume to give me for a present, and I told her she needed to keep her money, I didn’t need anything, but I cherished it. I brought it back here, and I wouldn’t let anybody touch it.”

Bryan Giemza remembers the time he was working in a small town in eastern North Carolina, and on his way back to Chapel Hill he encountered a man walking with a cane who asked him for a lift. The ride gave Giemza a chance to tell the Vietnam veteran he appreciated the sacrifice.

“I said, ‘My father was in Vietnam.’ It was a powerful moment because I saw the tears come to his eyes, and he said, ‘You know, you’re the first person that’s ever said that to me.’ And I think that says something about the reception that Vietnam veterans got when they returned.

Bryan Giemza ’99 (JD, ’01 MA, ’04 PhD), director of the Southern Historical Collection: “People might say something to one of Jim White’s high school students precisely because they are amateurs, quote-unquote.” (Photo by Grant Halverson ’93)

“But it says something else about the people who aren’t necessarily going to be on the radar of a team of professional historians.”

Giemza is among the latter, the director of UNC’s Southern Historical Collection and holder of Carolina law and master’s degrees and a doctorate (from ’99, ’01 and ’04). His job is to continue building what he calls “an embarrassment of riches,” the most prestigious archive of the American South, by acquiring the papers of prominent scholars and the artifacts of notable people, sometimes in torrid competition with other institutions.

But the collection would be less complete, and much less interesting, if it were limited to the work of professionals.

“Sometimes, in fact, we deflect scholarly collections, because,” he said, “what is the product? The product is a book; you might have some letters, research materials that you’ve accumulated, but they’re rarely primary. And our charter is specifically to collect primary material.

“So, enter the amateur historians.”

Pete Parham, 16 and in high school in Henderson, came out of a movie theater to the news on Dec. 7, 1941.

“We didn’t know what was going to happen, but we did know we were all going to be involved.”

As a senior he went to Durham to take an Army Air Corps exam, to try to beat the draft. Back home after training, he was assigned to a B-17 based in Tampa. His brother-in-law Bob got the same assignment. When they got there, Bob asked that Pete be assigned to him, and somehow it happened: Bob was the pilot, Pete the bombardier. They would fly missions out of Lavenham, England.

“We put on an electric heated suit. We had heated inserts for our feet. We wore electric heated gloves over silk gloves. We were able to plug ourselves into the electricity on the plane. In addition to all that, we wore a fur-lined jacket and pants and fur-lined boots. We had a leather helmet with built-in earphones. We wore an oxygen mask that was plugged into a central unit. We had a bottle of oxygen to carry with us if we had to change positions.”

On a mission over a fighter base near Brandenburg: “We got into Germany, real deep. We were a bit too far from the target for the bomb run, and we got hit about the hardest I have ever seen with fighters. The antiaircraft was terrible. We lost a bunch of planes and crews. I think about nine of our planes were shot down with these fighters coming in. It was just terrible. You could see the fighters jump on a B-17 that had been crippled and had to drop out of formation. The fighters would come in one right after another. I remember looking at one falling out, a B-17 that was crippled and the fighters came out of the air and finally shot them down. The crew went down, but they should have been proud of themselves before they went down.”

April 14, 1945: “It was rather an unusual mission. We were going to fly to the coast of France on the Royan peninsula. A pocket of Germans had holed up there ever since the invasion on D-Day. They had been bypassed, and any time planes would go over, they would shoot at them. It was a big problem. They wouldn’t surrender; we had to go in to see what we could do to knock them out. … For the first time in the war with Germany we were flying and using napalm bombs, which are a form of gasoline jelly. They were incendiaries. … Well, after two days of bombing them while the French navy and American Navy were shelling them from the coast, they were burned out literally. They capitulated and surrendered. So that ended the resistance in Royan peninsula.”

All this time, Parham was flying with his brother-in-law. Later they got separated, and Parham was on his way to fly on B-29s bombing Japan when the war ended with the Japanese surrender. Pete and Bob reunited at home.

Francis “Pete” Parham, interview excerpts

Francis “Pete” Parham, full interview (1 hour, 27 minutes)

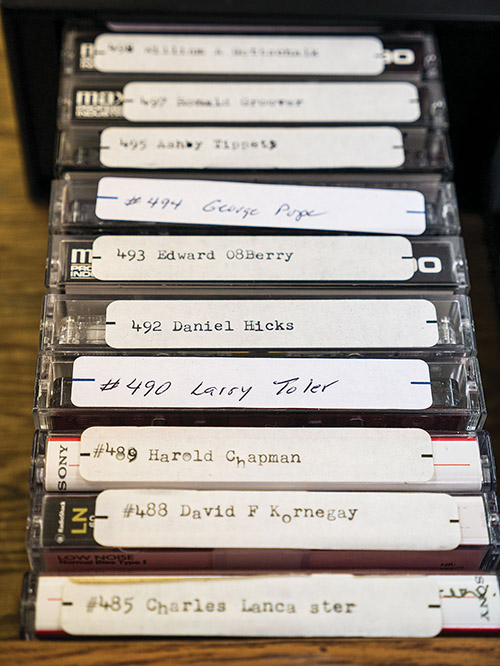

By 2010, Jim White had 1,092 interviews with 854 veterans. He had spread the project to his students at Pamlico Community College and at what then was Mount Olive College. They taped vets from every major conflict since the start of the 20th century, including three from World War I. The Library of Congress wanted the material; so did the National World War II Museum.

Some of the work of the community college students would meet the professional standards of UNC’s Southern Oral History program (which became independent from the Southern Historical Collection some years ago). Most of it would not. And that is OK with Bryan Giemza.

Most of Jim White’s students used cassettes. The library faces the challenge of digitizing hundreds of hours of tape before it can be accessed practically by the public. (Photo by Grant Halverson ’93)

“Even though some of those recordings are poor — some are downright miserable; these are not trained field researchers — I think there’s still something to be said for what they discover and what can be developed in the aggregate.

“The other piece to the amateur puzzle is, sometimes you get a rather wobbly result, but other times you get something that’s really quite unique. People might say something to one of Jim White’s high school students … precisely because they are amateurs, quote-unquote.”

The Jim White Oral History Collection in the Southern Historical Collection is what Giemza calls a community-driven or participant-driven archive.

First, there aren’t nearly enough professional oral historians to harvest all that’s out there. Second, the students who did the work were enriched with the experience; as White said, taping members of his own family is what got him interested.

And third, the telling can be intimately important to the teller. White recalls the veteran, dying of cancer, who heard about the project, asked to be interviewed and died the day after they put the transcript in his hand. “He was hanging on for that.”

Some, he said, had children who wanted their stories told. Others had not shared their stories with anybody.

John William Kraus and Joe Bergman landed at Inchon and were in some of the heaviest fighting in the Korean War. They were interviewed together.

Bergman: “At first I said, I don’t know if I can kill these people. They haven’t done nothing to me. Then I saw the Marines laying around dead, and it changed your mind about whether you could kill somebody or not, because you know you could be next.”

Kraus: “You don’t think of them as a person. The only thing you’re firing at is a target. So there’s no real face-to-face shooting, unless you come to hand-to-hand. And then you don’t care what anybody looks like. You’ve got one thing on your mind, that’s to survive.”

Bergman: “We got up to Ansan, and the place was so heavily mined that we couldn’t get in. So we stay out there while the Navy clears the mines away, and when we did get in there, Bob Hope was there to greet us [as part of a USO show]. Yes, he was. The ROK — the South Korean army — had already taken that by the time they got the mines free.”

Later they were at the infamous action at Chosin Reservoir.

Kraus: “That’s where it got sticky.”

Bergman: “We had 15,000 men going up there, and we got up there and we heard on the radio that elements of the First Marine Division are encircled by Chinese and had very slim chance of anyone coming out alive.”

The Chinese had more than 120,000 troops. Temperatures dropped to 35 below zero. Casualties were heavy after 17 days of fierce fighting — thousands died from the weather alone — and Kraus and Bergman were among the United Nations troops who made it out.

Kraus: “We brought out most of our dead and all of our wounded.”

Bergman: “You just don’t know until you’ve been there. I could tell you all day long. I’ve had nightmares ever since Korea. There’s nothing I can do about it. I just hope to God that none of these young fellows like you … never …”

John William Kraus and Joe Bergman, interview excerpts

John William Kraus and Joe Bergman, full interview (59 minutes)

Others have gotten the same idea as Jim White. Rusty Edmister ’66 (’68 MBA) took up an offer from a World War II vet he met at his gym to watch a DVD of his war recollections. The state Division of Archives and History was doing the interviews, and soon Edmister was in downtown Raleigh, telling his own Vietnam story.

But getting to Raleigh wasn’t so easy for a lot of vets, the retired salesman surmised. What if he bought a camera and went on the road for the effort? That was seven years ago, and the N.C. Military Veteran Oral History Project has 329 interviews on DVD. Edmister laughs when asked whether he had formal training in oral history; he just turned on the camera, and he was doing it not for an archive but for the vets and their families. Now he has three partners, all veterans, helping him look for interviewees and interviewers.

“They’ve always said, you know, ‘I ought to talk to somebody about these things,’ but that doesn’t happen, and the next thing we see is their obituaries,” Edmister said. “We let them talk about what they’re willing to talk about.”

Then he and his partners ask, “How many copies do you want?” Edmister and the state agency parted ways because, he said, the state put too many ground rules on the project. Now they ask another question: “Do we have your permission to place your interview at UNC?”

“I go back to the notion of people think of the archives sometimes as a dusty crypt,” Giemza said. “I don’t see it that way at all. I see it as a big party where all the voices of the past are kind of having a great dinner conversation about what happened. We’re all amateurs at telling our own stories where our perspectives are skewed a certain way. As the Russians say, no man sees his own ears.

“But each one of those voices is an important part of the party. The more of them we have, the better composite we have.”

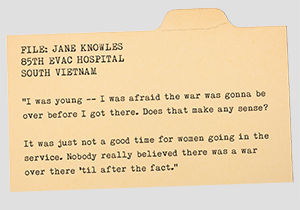

Jane Knowles studied nursing and joined the military in 1968 at age 26. She went to Vietnam the next year, assigned to the 85th EVAC hospital, Phu Bai, Republic of South Vietnam. She was a second lieutenant in a MASH unit.

“I was young — I was afraid the war was gonna be over before I got there. Does that make any sense?

“It was just not a good time for women going in the service. Nobody really believed there was a war over there ’til after the fact — so I’ve had so many of my friends say, ‘I wish I’d written you a letter.’ Got that guilt.

“It was about 30 miles by chopper to any hospital. The helicopters saved a lot of lives. Like, in World War II or Korea, those guys would’ve died. It depended on where the firefight was — where the action was, there was battalion aid stations — but most of the time they came straight to us from the field.

“Next to our compound was the air strip and the ARVINS — the Army of the Republic of South Vietnam, like their basic training camp. So the VC at night would lob some rockets and mortars in. … They’d do it in threes — one would be further away and one would be short, and that’s how they figured out how dead to hit.

“The biggest push we had was Hamburger Hill. We were getting them in 75 at a time. We were so busy with casualties that we were waving them south. For two solid weeks, every day at the same time we would start getting casualties. After they got the hill, they just pounded it and pounded it and pounded it. And they just walked away and left it.”

After the war, in Texas, Knowles was spit on while in uniform. She stopped in a store and changed into civilian clothes, and later she was ashamed she had done that.

“I had to come home and hide my uniform to keep from getting pushed around. You didn’t wear the uniform if you could help it. … You didn’t want to call attention to yourself.”

Edward Eatherly Bridges thought the Army would help him find a direction for his life. He entered Special Forces training shortly after being commissioned a second lieutenant in 1960. The “entrepreneurs of the Army,” as he called them, were in ahead of the buildup of troops in Vietnam, doing intelligence work, developing rapport with the Montagnards, the indigenous peoples of the Central Highlands — training them and learning from them.

When Bob Wilson came to talk to him about it in the late 1980s, Bridges described the wonder of a bale of money dropped by parachute so he could supply his men; what you ate when C-rations were prohibitively heavy to carry; how to make a bazooka and explosives from household items.

Bridges returned to the war as it shifted dramatically with the buildup of regular American troops, making his a unique perspective on a conflict that remains difficult to understand.

You could read the CliffsNotes about Vietnam, or you could read the James R. Wilson Collection of the oral histories of Vietnam veterans in an afternoon. It’s three boxes of transcripts — vivid drama and mundanity, but unvarnished. The Red Cross aide who recalled the men in her college classes trying everything to keep their exemptions; the guy who broke past security at an air show to ask a Marine what he had to do to become a Marine pilot; the people who killed and were terrified and who got back.

Wilson’s quest started in a graduate course at Duke University about the nature of war. A press officer in Vietnam and a retired journalist, he knew how to “construct a tree” whose branches would lead him through a network of veterans. His wife, Betty Krimminger ’72 (MSW), had worked extensively with researchers in the Southern Historical Collection. When Giemza came over to listen to his tapes and read his transcripts, there was no question where the material would go.

“As in so many wars, the Southerners carried a disproportionate share of the burden,” Wilson said. He traveled about 12,000 miles in two years gathering interviews. “It was immensely satisfying.”

David E. Brown ’75 is senior associate editor of the Review.

All italicized excerpts are from the Jim White Collection, which still is being processed by the Southern Historical Collection at Wilson Library; as is Rusty Edmister’s N.C. Military Veteran Oral History Project. The James R. Wilson Collection can be read at the SHC. Select portions of each of the collections will be digitized as funding is available.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.