Nomad Who Takes Notes

Posted on Jan. 11, 2018

Stephanie Elizondo Griest spent her 20s evading burdens like a house, a partner, a job or children or pets — anything that would have distracted her from capturing the world in words. (Photo by Alexander Devora)

Stephanie Elizondo Griest flips back her silver-and-black hair and introduces the scene. A priest is blessing the crowd at a church in Mexico, and parishioners are collapsing to the floor in rapture.

“So to re-create that rapture, I am going to invite up the most rapturous woman I know,” Griest says. “Jennifer Curtis, join me on violin.”

Griest’s appearance at Chapel Hill’s Flyleaf Books isn’t a mere reading — it’s a miniature stage show.

Curtis, a former visiting professor at UNC, is a Bach virtuoso who has played solo concerts at Carnegie Hall wearing elegant gowns. Today she is in cowboy boots in front of a crowd of 80-plus who have gathered on an August Tuesday in Flyleaf’s back room. She punctuates Griest’s phrases with flourishes and vibrato — the two-tone sound of an ambulance siren.

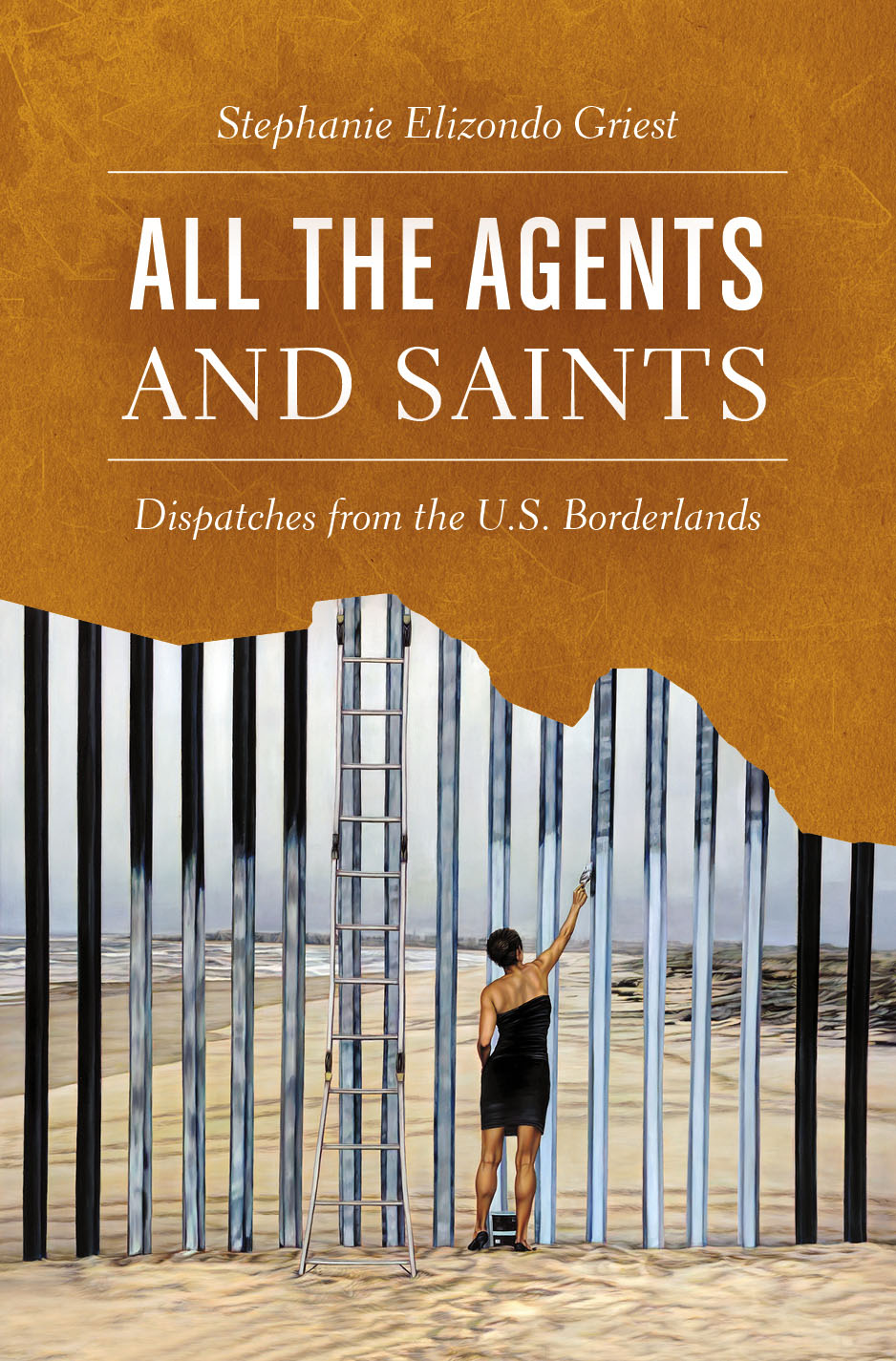

All the Agents and Saints: Dispatches from the U.S. Borderlands

For a decade, Griest, an assistant professor of creative writing at Carolina, has immersed herself episodically in the lives of people living on our southern and northern borders, attending their celebrations and worship services, eating their food, listening to their stories. It’s produced the newest of her three books, All the Agents and Saints: Dispatches from the U.S. Borderlands.

Griest herself walked away from Catholicism, just as she did her Hispanic heritage. She is from the borderland town of Corpus Christi, Texas. Her mother is Mexicana, her father is a white man from Kansas, and she learned early on that there were advantages to identifying as white. Still, the border that ran right through her inspired a lifetime of living differently. Of traveling, of being rootless, of gobbling life.

She spent her 20s as a nomad, evading burdens like a house, a partner, a job or children or pets — anything that would have distracted her from capturing the world in words. What she calls her “raging case of wanderlust” has taken her to 49 states and 46 countries, including Lithuania, Mongolia, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Egypt, Albania, Burma, Venezuela, Cuba, Rwanda, Swaziland and Mozambique.

Now she teaches her students this — to live and listen intently, to write everywhere, all of the time. To paint with their pens.

Griest and Curtis have been a couple for three years, and together they’ve performed in Bolivia and Austin, Chapel Hill and Corpus Christi, their collaboration a result of mutual inspiration. Curtis is a genius at improvisation, Griest said, who can follow anything from an instrument she never heard of in Rwanda, to African drumming, to classical Indian dances.

“I just read it, and she instantly comes up with what is going to make it meaningful,” Griest said. “She deeply understands pauses and silences and knows how to play people’s heart strings with her violin strings, so it’s all her.”

That last bit is not entirely true. Griest is a master of her own voice — of her cadence and pacing, the staccato bursts and sustained strings of s’s. She was mentored during a Hodder Fellowship at Princeton by the renowned narrative nonfiction author John McPhee, and she writes with a paintbrush, exploring the devastation of the United States’ border lands — the devious treaties, the loss of mother tongue, the devastation of traditional ways, the toxic waste seeping into native lands — through the stories of the people there.

Her first book, Around the Bloc: My Life in Moscow, Beijing and Havana, sprang from four years working as a journalist in Russia and meeting people who had sacrificed nearly everything to uphold their indigenous culture, even in a state of totalitarianism.

“I continuously found people who made sacrifices to honor their ancestry,” she said, “and I realized that I had abandoned my own by not learning Spanish or being Catholic. Instead of being around the bloc, I needed to go to my own block.”

So for her second book, Mexican Enough: My Life Between the Borderlines, she moved across the border.

“Living there for a year made me realize I will never be Mexican, not even if I move there for the rest of my life, because what binds a people are their bedtime stories, their childhood poems, their prayers, their shared memories. Mine are not from Mexico — they are from the liminal space between Mexico and the United States.”

She returned home in 2007, but Corpus Christi had changed. Her sleepy, boring hometown, the one she couldn’t get away from fast enough growing up, was a major news story, poisoned by the petrochemical industry, militarized by the border patrol, barricaded by a wall. For six years she studied the people there, scribbling notes. Always scribbling notes.

Then chance and a visiting professorship at St. Lawrence University took her 2,000 miles north, to the space where New York meets Quebec, where the lives of the Mohawk of the Akwesasne Nation mirror the colonial devastation of the southern border. It took a decade of immersion to produce Agents and Saints. Now she is plotting her travels for her next book, Art Above Everything: Global Women With a Single Vision, which asks a universal question.

“Can you have a fulfilled life if you don’t have children or a traditional family, if you live entirely for your art?” she said. In many of the places her research has taken her, she has found women who are pouring their lives into their art, creating extraordinary things by shoving aside expectations and norms — the “shoulds” — and investing their energies in the act of creation.

Griest and Jennifer Curtis have been a couple for three years, and together they’ve performed in Bolivia and Austin, Chapel Hill and Corpus Christi, their collaboration a result of mutual inspiration. (Photo by Alexander Devora)

She and Curtis each have done that, and now they are blending their creative spirits in a new way.

“Every time she touches that violin something magical happens,” Griest said. “I think her music rearranges me at the cellular level. She feels the same way about my writing, so we thought it would be special to merge the two.”

Griest also has put down tentative roots. She has lived in Carrboro for four years — the longest she has lived anywhere as an adult — and she is grateful, she tells her audience at the reading, for being allowed to belong.

Hers has been a life of adventure. And now the couple are on a new one. Shortly after their Flyleaf performance, Griest felt unwell. She chalked it up to the book tour, to too many enchiladas and too much time on the road. It was ovarian cancer. Her treatment and this swerve on her life path will be woven into her next book, but the diagnosis has clarified one thing for her: A life lived for art is a life very much worth living.

“Jen and I have made our own work our priority, and I feel like this experience is showing me that, yes, it is worth it.”

So now her book is out there, and she can’t continue her book tour.

“Gave 10 years of my life to my book. I feel like I’ve abandoned it, and that’s devastating.” To this writer, she adds, “Thanks for giving it a little puff of air into its little lungs. I feel like it’s gasping on the side of the road, trying to live.”

As for herself: “My entire life I have felt like I was two steps ahead of a black hole. That’s why I have lived and traveled so ferociously, why I’ve done everything excessively, because I’ve always felt keenly that my time is limited. If this is the end, then I’m so glad I lived the way I did. I’m crazy lucky.”

— Janine Latus

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.