On Her Majesty's Service

Posted on March 8, 2018

The world-famous suspension bridge spanning the Avon Gorge and the River Avon, linking Clifton in Bristol to Leigh Woods in North Somerset, is not a bad metaphor for the goals of Peaches Hauser Golding ’76: to connect working-class areas with wealthier ones in addressing social mobility, health care and education. (Jim Ross/AP Images for the Review)

Peaches Golding ’76 prepared herself for any opportunity. In the unlikely event that the Queen of England would come calling, she was ready with grace, poise and a knack for building bridges among people.

by Christine Fundak Rohan

Two paths lead to Charlton, Peaches Hauser Golding’s modest Bristol home of 32 years: one from the busy front road, the other from the quieter back one bordering an ancient forest with views over the Avon Gorge and iconic Clifton Suspension Bridge. Both paths lead past well-tended plants — roses, crocosmia, fuchsias, cyclamen, asparagus, rhubarb — to the front door, where a pair of gardening shoes lie kicked off beside the mat.

Golding, class of ’76, opens the door in bare feet, skinny jeans and a loose sleeveless top, her face defined by a bold pair of cat-eye glasses and dangly earrings that swing as she talks. Nothing about her seems remotely royal, certainly not her name — although she was christened Lois Patricia, she’s been called Peaches since birth, when an aunt and uncle said her complexion resembled the fruit — and yet Golding is, in fact, a lord lieutenant, a personal representative of Her Majesty the Queen of England.

Golding greets the queen at her investiture into the prestigious Order of the British Empire at Windsor Castle. (Courtesy of Peaches Hauser Golding ’76)

Considering that aristocrats traditionally occupy this role created by Henry VIII in the 1540s — originally, lord lieutenants organized their county’s militia, but now their role is largely honorary, awarded to one notable individual per county — how this self-described “ordinary girl” landed it spurs many questions.

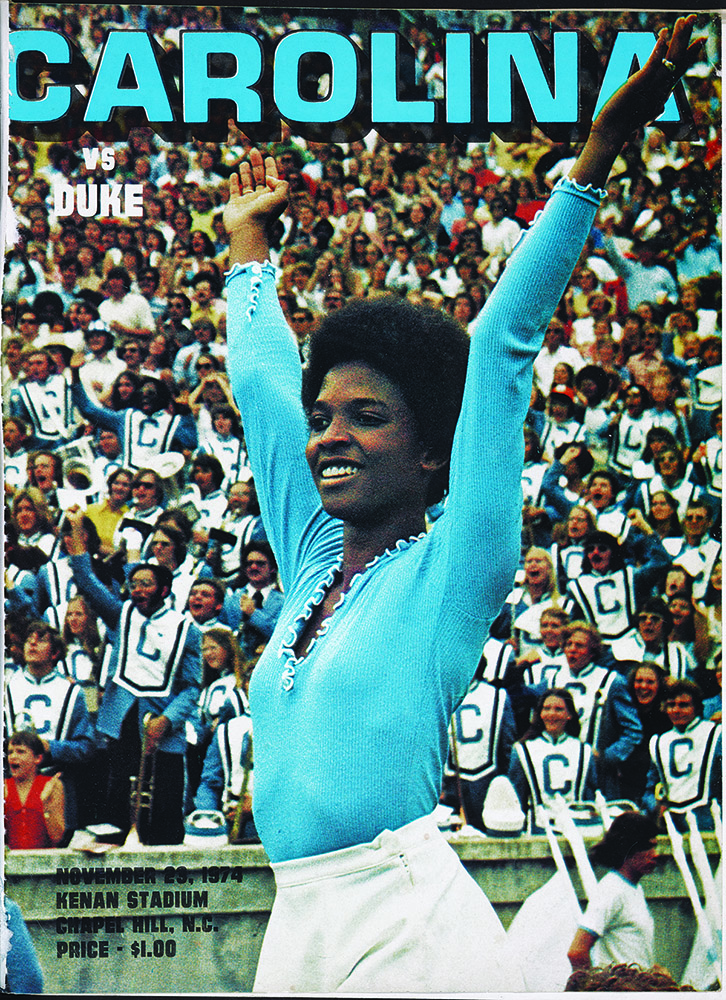

Golding provides plenty of answers as she moves from the door to her bright plant-filled living room, dotted with eclectic artifacts, including a python skeleton from one of her many global adventures. She moves with distinctive poise, her petite frame lithe, and her back perfectly straight; her warmth, humor and hospitality are disarming. (As a student at Carolina, she choreographed dance moves for the cheerleaders and performed solo to a standing ovation at her last home basketball game. Jill Coleman ’76, a fellow cheerleader at Carolina, said she “had a beautiful way of moving. If you saw her across a crowded room, you’d notice that about her.”)

“I love what people do — I’m interested in people,” Golding said, offering a cup of tea before telling the story of how her journey to Buckingham Palace — where she’s met the “tiny queen with piercing blue eyes that focus 100 percent on you” multiple times — began in Africa.

“Life is never direct,” said Golding, who was born in Spartanburg, S.C., a descendant of a white plantation owner and a black slave. Her family later moved to Winston-Salem, and after graduating from UNC in zoology, she set off for Ibadan, Nigeria, with just a suitcase and a cat. She was confident she would land a job, and she did — as a dance teacher for expatriate children and as an English teacher at a boys’ high school.

Golding’s home conservatory is her getaway from the formalities of royalty. She and her husband, Bob, recently built an upgrade with double glass and a heated floor. (Jim Ross/AP Images for the Review)

The course of her life was altered by meeting zoologist Bob Golding, the Bristol-born director of Ibadan Zoo, with whom she shares a birthday, an affinity for flowers and snakes, and a son. Three years after they met in Ibadan, she came to England, embraced British life with her characteristic zeal and married Bob in 1981.

When Bob Golding’s work moved to Cotswold Wildlife Park, Peaches Golding took on its public relations role, despite having no prior experience. In 1983, when she arrived in Bristol, southwest Britain’s largest city, she landed a marketing job and absorbed everything she could about property development. She moved to the city council’s economic development office, working in efforts to draw new businesses to the city.

Next was the Aluminum Can Recycling Association. “We were the first in the U.K. to say, ‘Don’t put that can in the dustbin!’ ” she said. Golding and her team persuaded U.K. retailing giant Tesco to participate. “We got the metal merchants to collect from Tesco, Tesco’s sales spiked, and the U.K.’s recycling revolution started.”

In 1992, she started her own marketing consultancy and encountered the Training and Enterprise Council, a government body that ensured alignment among education, training and employers’ needs, and directed an independent radio station.

Through the council, she received an invitation in 1994 to St. James’ Palace, to the Prince of Wales’ reception recognizing U.K. diversity. Bewildered, she mingled with archbishops, business leaders, politicians.

Peaches Hauser Golding ’76 talks about her incredible life, and being made Lord Lieutenent of Bristol.

“I was one of the few black people identified then who had blue-chip customers: Two of my clients were in the top 100 U.K. companies. The Prince of Wales supports many charities; one was examining the barriers to people of minority ethnicity in mainstream business — i.e., why don’t we see ads with black people’s faces? Why is no marketing directed to this growing sector? Why aren’t businesses owned by black people supplying mainstream businesses? They asked me how I got onto the supply chain, and before I knew it, I was deputy director of the Race for Opportunity campaign,” run by one of Prince Charles’ charities that aims to build sustainable links between minority ethnic communities and society. “I worked with this charity for 18 years.”

Golding built bridges between minority ethnic communities and the larger society. She led conferences and workshops to educate business leaders about their roles in improving racial diversity in their workplaces; introduced a jobs fair in Bristol targeting minority ethnic job seekers; and escorted business leaders to a mosque and Sikh temple to help them learn about these religions.

“My dad did all sorts of things to help people realize their opportunities, to inspire them,” she said, referring to the late Charlie Brady Hauser, a legislator and Winston-Salem State University professor. “So I put my hand out, too, to pull other people up.”

“We could do anything”

In the Winston-Salem of her youth, the neighborhoods, parks and restaurants were segregated; the biggest employer’s bathroom doors read “White Women, Black Women, White Men, Black Men.” Golding never envisioned what her future held for her.

“I grew up in segregated America when it was against the law to cross state lines with my current husband. How could I ever? But, growing up with Martin Luther King’s wonderful words, how could I not ever?”

Her sister Fay Hauser-Price ’71, a producer and actress known for her role in Roots: The Next Generations, credits her and Golding’s success to their parents. “Despite growing up in segregation, they made a good life in the South but didn’t let that stop them from pushing against the envelope whenever possible. Our dad challenged Jim Crow laws on a Greyhound bus in 1947, eight years before Rosa Parks, and won.” Specifically, Charlie Hauser sued the company for trying to make him give up a bus seat.

“When you have something to push against, it causes you to dig deep and be proactive to actualize what you want. You can’t sit back and assume it will be given to you or that you deserve it. People did well because they didn’t allow that attitude to stop them going forward.”

Golding, who choreographed dance moves for the Carolina cheerleaders, performed solo to a standing ovation at her last home basketball game. (Courtesy of Peaches Hauser Golding ’76)

Golding’s sociability and dancing talent gave her visibility in high school and college dancing and cheerleading squads. “I knew Peaches. We all did,” said Karen Blair, a Virginia artist who graduated with her from Reynolds High School in 1972. “She was a standout — smart, energetic, beautiful. We were part of a large school integration program that blended previously mostly black and mostly white schools into one large high school, and Peaches was one of the black students who mixed most easily.”

Their mother, a first-grade teacher, encouraged her daughters in their interests. For Golding, that meant learning ballet and keeping a fish tank and a colony of ants in the dining room. As teachers, both parents had summers off, and the family traveled widely. These trips, plus meeting the foreign academics their father invited home and learning Spanish at a young age, helped open Golding’s mind to the world.

“We were in Washington when Kennedy’s funeral cortège went past, when Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his ‘I Have a Dream’ speech. We were in Florida to see NASA, in the Outer Banks where the Wright brothers flew their airplane. We went to the World Expo in Canada. I knew where the news was because we were there. We could do anything, we did anything, so perhaps I had an overinflated self-belief. No one could ever puncture my balloon.”

Lord lieutenant

“Peaches is everywhere. If you have a piece of fabric, she’s the recurring pattern in it. She constantly brings business to the table and mobilizes people to take action, to do something,” said Andrea Callender, former Race for Opportunity campaign director. “She lives by her values: that business should be a source of good, that communities need empowerment and focused action, and that businesses can’t operate in a vacuum — they need to invest in their communities. St. Paul’s is a deprived Bristol area, for example, and Peaches has helped business engage with that community. That’s what she’s being recognized for.”

Her regalia as lord lieutenant of the County & City of Bristol. (Jim Ross/AP Images for Carolina Alumni Review)

Golding is a recipient of the prestigious Order of the British Empire. In 2010, she was appointed high sheriff of the county and city of Bristol, an honorary, nonpolitical one-year royal appointment that supports law and order — the first black woman in its 1,000 years. She received an honorary MBA and an honorary doctorate from the University of the West of England.

But her crowning glory came in April 2017, when Queen Elizabeth II named her lord lieutenant for the county and city of Bristol. Apolitical and unpaid, it is a 10-year appointment.

One of her main tasks is to arrange and escort visits to Bristol by the royal family, whose soon-to-be 18 working members annually undertake more than 3,000 visits, nationally and internationally. Golding already has hosted Princess Anne, the current princess royal; now she’s coordinating with five royal residences — Buckingham, St. James’, Clarence House, Bagshot Park and Kensington — and relevant local organizations to plan the Duke of Gloucester’s upcoming visit in five-minute increments. It’s an exhaustive process, but it enables the monarchy to stay connected to the people and local organizations to raise their profiles.

“Our royal family doesn’t think of life in terms of what it means next year,” Golding said. “They think in 100-year timeframes, maybe even longer. It’s a historic role of enormous weight and importance, integral to British life. The queen sees the prime minister weekly: This is how this country works, and I’m in the middle of it. I have to regard history and tradition while understanding what I can modernize, so I’ve changed the website to make us more visible and relevant, especially to young people, and I tweet (@PeachesTweets), which is why I haven’t time to tidy up my office.”

“This role changes your life, but to be asked to be the queen’s personal representative, how do you say no? What is a bigger gig, a greater honor, than that?”

— Peaches Hauser Golding

The phone rings on the paper-strewn desk in the home office she shares with her husband and a half-dozen orchids in mid-bloom. “Good morning, Peaches Golding speaking. Oh hello, Sheila, I’m perfectly fine, thank you. … Is the station master involved in that at all? I know that when the royal train came in, the station master obviously was involved …”

She hangs up five minutes later, apologizing. “That was my PA. We have the duke’s visit next week, so I’m arranging for him to visit a hostel for 16- to 25-year-olds at risk of homelessness. We’re going there because this particular organization has good links with a Realtor and is helping these young people acquire skills in construction, which has a skills shortage. The duke will present certificates to those who’ve completed their apprenticeship course, which is wonderful: This is a potential path out of homelessness for them. This is how I as lord lieutenant can highlight what the city is talking about and add a little royal fairy dust to that conversation.”

Being relevant is Golding’s overarching goal for her diverse city of 430,000 people from 187 countries, with 91 languages and 45 religions. “All the things that can pull us together are things we need to do,” she said. “Besides homelessness, we have — oddly enough — slavery to address: Bristol was Britain’s No. 2 port in the 1600s and 1700s and consequently heavily involved in the slave trade, before it moved to Liverpool. But the city has a legacy, a tension we need to discuss.”

There are several key issues she wants to address: enterprise creation and international trade, social mobility, reducing gaps in health care, education and achievement among historically working-class areas and wealthier ones, and working to inspire young people.

Bob Golding, who occasionally accompanies his wife on official engagements and maintains her lieutenancy website, said: “I made sure before she accepted Prime Minister Theresa May’s invitation that she’d use her deputies fully. The responsibility on Peaches’ shoulders is huge, but it’s an amazing thing, and I think she’ll do a good job because she’s different. She’s not steeped in history; she’s got modern ideas.”

Golding with Prince Charles when she served a year as high sheriff. (Courtesy of Peaches Hauser Golding ’76)

Golding received her appointment after the Privy Council (the queen’s formal body of advisers) consulted for two days about “the good and great” — those who are knowledgeable or willing to learn about their county and its issues and are good communicators, well-respected, relatable, tactful, discreet and impartial. “About five names go to the prime minister, who decides and then writes to you,” she explained. “You have a fortnight to deliberate; if you consent to your name going to the queen, you can’t back out.

“This role changes your life, but to be asked to be the queen’s personal representative, how do you say no? What is a bigger gig, a greater honor, than that?”

And, to the question you might be asking, does the queen call her Peaches?

She has. Golding is presented to royal visitors as Peaches Golding OBE.

Ambition and integrity

Golding now faces another challenge: She underwent treatment last summer for primary-stage breast cancer, and she was surprised at how much it had taken out of her. Her treatment was public knowledge, and she was typically upbeat.

Golding at her home in Bristol. (Andrew Crowley/Telegraph/Camera Press/Redux)

She shares England’s excitement over the engagement of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle. Golding has four royal visits to Bristol to handle in the wedding month of May, though she’s not at liberty to say which members of the family are involved. (Given the size of the wedding venue, she doesn’t expect an invitation.)

Back in July, before starting cancer treatment, Golding had lunch plans in nearby Clifton Village with some of UNC’s newest honors students, visiting England on a weeklong orientation program, and swapped jeans for a dress, cardigan and walking sandals. She considered bringing her gleaming lieutenancy badge or the beautifully encased parchment signed by the queen authorizing her as lord lieutenant but didn’t. Instead, she plucked a bloom from Bob’s huge hibiscus collection in their conservatory, tucked it behind her ear and took the back path from Charlton.

She was running late but maintained her pace (“Southern ladies don’t rush”), pausing to laud engineering genius Isambard Brunel as she crossed his magnificent suspension bridge. Locals greeted her familiarly; she was well known here even before the media frenzy that accompanied her recent appointment.

At lunch overlooking the spectacular Avon Gorge, Golding was in her element, conversing, laughing, making friends. Later, when she was at the front of a meeting room talking about her life’s unpredictable path, she started with the somber side of her ancestry, the fact that her great-great-grandmother was purchased in 1853 for $450. It is a fact that she says has shaped her.

Weeks later, freshman Elisa Kadackal still recalled Golding’s story, her steely confidence and simple explanation for her success: “presence is power.”

“Throughout her life, Peaches was forced to prove herself in areas where others did not, and she did so by asserting her ambition and integrity at all times,” said Kadackal, who is of mixed heritage. “To this day, I’ve been empowered by her words and refer to them constantly as a reminder of my own potential. Peaches truly inspired me in a way I can never forget.”

Christine Fundak Rohan is a freelance writer based in London.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.