Second Calling

Posted on Sept. 24, 2021

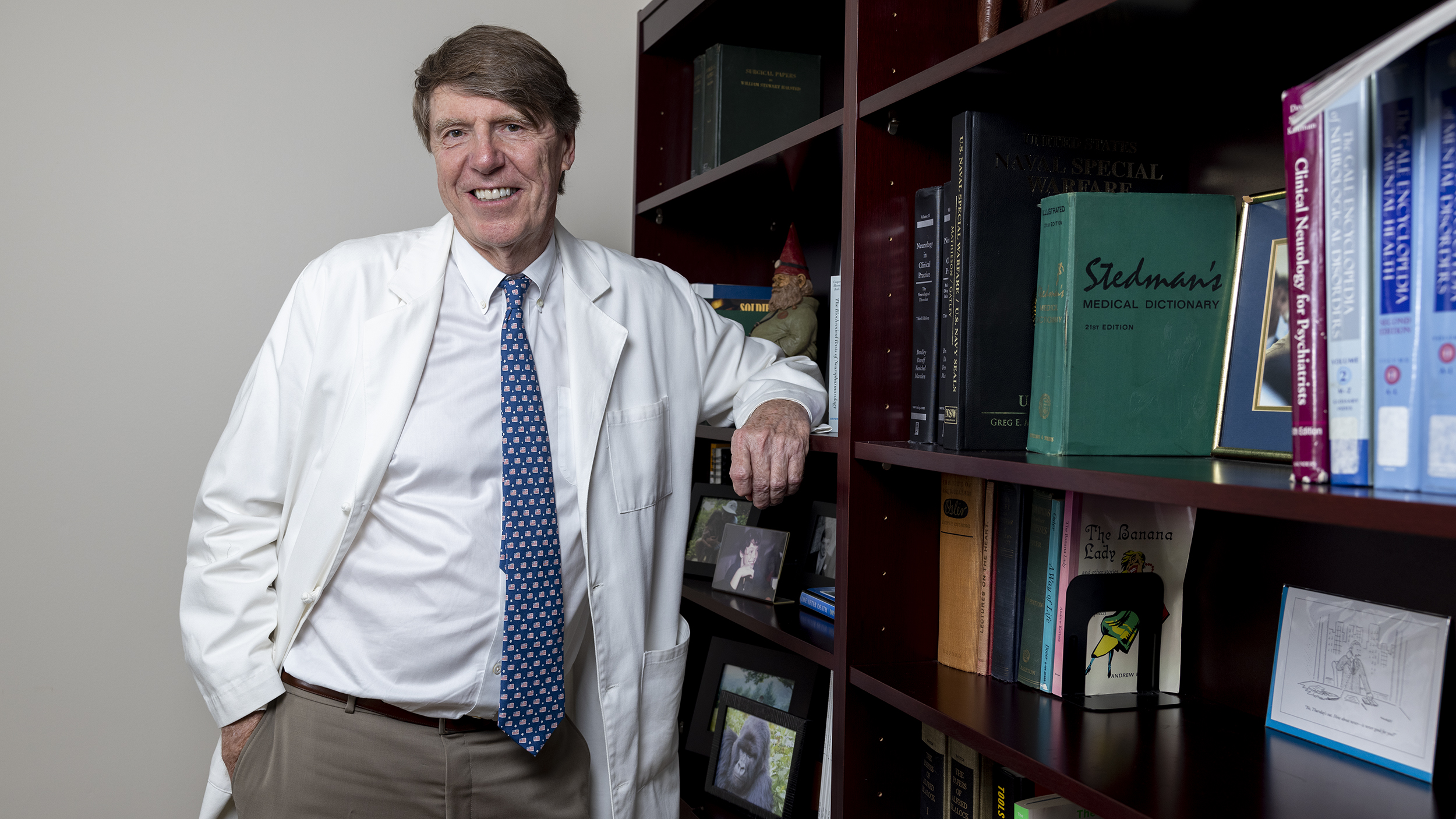

(Grant Halverson ’93)

When a hand tremor interrupted his career, surgeon Chuck Edwards ’73 (MD) drew on his parents’ battle with Alzheimer’s to reinvent himself.

by Elizabeth Leland ’76

One small shake changed everything.

When Dr. Chuck Edwards ’73 (MD) stood over the operating table, he knew exactly where he belonged. For three decades, the Charlotte cardiovascular surgeon had repaired the lives of countless patients, his hands steady as he sawed open chest cavities and gently mended damaged blood vessels. He performed bypass surgeries, valve operations, aortic replacements, chest and vascular surgeries.

But when an assistant noticed a tremor in his left hand during a surgery in 2010, the 62-year-old faced an existential question: If he couldn’t be a surgeon, who would he be?

“The idea that at some point, there would be the image of this old guy trying to be a heart surgeon, that’s not how I wanted the story to end,” said Edwards, whose tremor has never reached the stage of disability. “I didn’t want that path.”

Edwards, who earned his medical degree from Carolina and completed his residency and a fellowship in thoracic surgery at Duke, had always believed he was born to practice medicine; leaving the field was never an idea he entertained. In 1983, he started a heart clinic at what is now Novant Health Presbyterian Medical Center. For 29 years, he had “cherished the entire ballet, especially the patient waking up after a successful operation.”

He took particular joy in connecting with patients. As he wrote last year in his book, Much Abides: A Survival Guide for Aging Lives, Edwards began each patient relationship in the same way: “I had a four-legged stool that rolled across the floor of the exam room. I’d roll up, put my hands on the patient’s knees and say, ‘Tell me about yourself!’ Often the response would be something along the lines of ‘I have this pain or symptom.’ ”

He would stop them.

“ ‘We’ll get to the problem in a minute, first I want to know about you.’ ”

He loved hearing their stories. What they told him served as “a constant reminder that this was not just another patient with chest pain. It was a person with a life who needed someone to fix their chest pain so they could go on with that life. It was the link that kept everything in perspective.”

Chris Jones, the spouse of one of Edwards’ patients. “Even now, with all the demands of patients, when he first meets a patient he still sees them for two hours. He has tremendous empathy.” (Grant Halverson ’93)

As he wrestled with what he should do instead of surgery, he realized he would miss the stories the most. And after more than a year of soul-searching and moments of despair, those stories — and the stories of his parents — helped Edwards rewrite his own.

Both his parents died from complications of Alzheimer’s disease, his father at 75, his mother at 76. Although Edwards had extensive connections within the medical community, overseeing their care had been a constant battle. His days were overcome with feelings of helplessness, frustration and inadequacy.

The memory of those painful years led him to an idea: He would start a nonprofit clinic in Charlotte for dementia and Alzheimer’s patients and their caregivers. By opening a memory clinic, he could stay relevant in medicine — and connected to patients. Alzheimer’s disease was already the fifth-leading cause of death for people over 65, and he knew the need for his help would grow exponentially as baby boomers aged.

Edwards had discovered that little shake in his hand was an intention tremor; related to aging, it is the most diagnosed tremor in patients. Unlike the resting tremors associated with Parkinson’s, intention tremors occur only when the limb affected is prompted to perform an action.

Now, Edwards’ tremor was prompting him to write a new chapter.

“If I had not had the tremor, if I had not had my career shortened, then I never would have had this part of my life open up, which has probably been the most satisfying stage of my medical career,” Edwards said. He often recites quotations to make a point; this time, he quoted the storyteller Donald Davis: “It is never tragic when something bad happens. If you can use it in the right way, it will buy you a ticket to a place you would never have gone.”

Back to school

Edwards was bubbling with excitement when he shared his plan with his wife.

Throughout their 50 years of marriage, Mary Edwards ’71 has served as a check on her husband’s impulses. Chuck always was brimming with ideas, energy, questions and sometimes unfiltered opinions.

After the 9/11 attacks, he had wanted to enlist full time in the military. A surgeon had saved his father’s life during World War II, and he wanted to be that surgeon during the Iraq War. But Mary had no interest in uprooting from Charlotte, where they raised their three children, to start life over on a military base. He volunteered instead at an Army combat support hospital in Baghdad, where he served several months.

This time, Mary pointed out that Chuck had no expertise in gerontology. She dismissed his proposal for a memory clinic as “just another one of his big ideas.”

Chastened but undeterred, Chuck decided to go back to school. He wrote to several medical centers, beginning each letter with self-deprecating humor: “When a 64-year-old cardiac surgeon applies for a dementia fellowship, it prompts the question, ‘Shouldn’t he be in the clinic instead of starting it?’ ”

Edwards realized he would miss the stories the most. And after more than a year of soul-searching and moments of despair, those stories — and the stories of his parents — helped Edwards rewrite his own.

Edwards gained acceptance to Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, which had never welcomed a student his age for such training. But Hopkins was as interested in preparing medical professionals in Edwards’ age group to serve in the growing field of memory loss as Edwards was in reinventing himself. Instead of a two-year fellowship, Hopkins developed a shorter, noncredit program for Edwards, during which he attended lectures and conferences on dementia, psychiatric illness and psychotropic medication and assisted fellows as they treated patients in clinics.

He was humbled by his new surroundings. He was accustomed to being the lead surgeon in an operating room. At Hopkins, he was supervised by staff and fellows and had no direct responsibility for patients.

Those experiences would prepare him for the transition that lay ahead.

Dr. Peter Rabins, founding director of the division of geriatric psychiatry at Hopkins, offered two pieces of advice that have stayed with Edwards: “Heart surgeons are used to fixing things. You are not going to fix anything in this new career.” Also: “In geriatric psychiatry, listening is crucial to effectiveness.”

Edwards’ bespoke curriculum was designed to prepare him to open a memory clinic of his own, and after four months, Hopkins told Edwards he was ready. So, too, was Mary. By the time Chuck had rented an 800-square-foot office space in Charlotte, Mary had jumped in to help plan the venture. She scoured second-hand shops for furniture, helped paint the office walls and offered to be the receptionist. Memory & Movement Charlotte opened in December 2013.

Mary Edwards, who had stayed home to raise their three children, launched a career for the first time at age 65.

“I just fell in love with it,” she said. “I told him, ‘Chuck, these people need you.’ Patients would come out of his office, [let out] a big sigh, and say, ‘Wow, that felt so good to have somebody care.’ You couldn’t help but get chills that something good was happening to these people who were so overwhelmed with what this disease does to the patient and caregivers.”

Chuck, Mary and one registered nurse ran the clinic during its first months. He took no salary their first year; Mary volunteered without pay for five years. Now, 17 people work at Memory & Movement, including two other doctors, serving 1,000 patients and 3,000 caregivers at any given time. In addition to treating families affected by Alzheimer’s disease and dementia, the clinic has expanded to serve people with Parkinson’s and other movement disorders.

Edwards painted the illustrations that appear throughout his book to make the point that you don’t have to be particularly good at what you do. “As we age,” he writes, “we must accept that we will no longer always be good at things. … What is crucial is doing things that we enjoy and find valuable.”

“I have huge respect for my husband,” Mary said. “What was so amazing about this transition, every day and every night, he would read and read and read, and he taught himself what was important. And if anything presented itself in a patient, he was learning it. He was 67 at the time and voraciously learning. He’s been amazing about that.”

Bill Jones ’70 (JD), a former chief District Court judge for Mecklenburg County, was among Edwards’s first patients. Jones was 6-foot-2 and still strong. His 4-foot-11 wife, Chris, no longer could control the increasingly volatile impulses brought on by Bill’s Alzheimer’s disease. The 30-minute neurology appointments they attended every six months were not addressing their needs. A friend recommended Edwards’ clinic.

“The minute I stepped in that door of that practice, I knew things were different,” Chris Jones recalled. “The first meeting was two hours. Chuck not only did the [neurological] testing, but he established a relationship with Bill. They formed that rapport in the most wonderful, funny, caring way.”

Edwards rolled across the exam room on his four-legged stool. He put his hands on Bill Jones’ knees and said: “Tell me about yourself.”

The doctor and the judge found their common ground in basketball. Jones played in high school in West Virginia. Edwards, who is 6-foot-6, was a walk-on at the University of Virginia. He was cut from the team after freshman year — a humiliating rejection but also fortuitous, he said, because it allowed him to focus on medicine.

The day of Bill’s first appointment, Edwards also spent time alone with Chris and their two sons, Brian ’00 and Eric ’03, answering their questions while the nurse attended to Bill. “Chuck included everybody,” Chris said. “His mission was to help the caregiver and support the caregiver as much as the patient. Chuck said to me, over and over, take care of yourself because numbers of caregivers die from [the stress of] taking care of Alzheimer’s patients.”

Bill died in 2015 at age 69. Chris now volunteers at Memory & Movement Charlotte running support groups for caregivers, a fulfilling new mission for the seventy-something. Brian Jones serves on the board.

“I think of Chuck as a wonderful friend in terms of listening, caring, dropping everything,” Chris said. “Even now, with all the demands of patients, when he first meets a patient he still sees them for two hours. He has tremendous empathy.”

The next chapter

Edwards would never have imagined it on the day when his assistant noticed his left hand shaking, but the past seven years have been the most satisfying of his career. He knows he made the right decision, stepping down before he had to.

“There are a lot of heart surgeons,” he said. “There are not too many people, at least in Charlotte, North Carolina, who understand dementia and understand the impact it has on families and the tragedy it is. I get to move into that space, and I’m part of their lives. That’s a gift to any physician that they allow you to come in there.”

He doubts he would have felt that same appreciation when he was starting out in medicine in his 30s. “I wanted to make big incisions and big surgeries,” he said. “At this stage, it’s given me a tremendous amount of feeling of gratitude towards the whole profession and gratitude toward my patients all the way to the end. Patients teach you as long as you have the stamina and will to follow it and learn from it.”

Edwards knows he is lucky to have found such a rewarding second calling when many others struggle in retirement.

“The hardest thing in the world is to change personal behavior,” he said. “How do you adjust to the demands of age? You keep moving on. The idea that I would take a saw and open someone’s chest now is foreign to me. … That guy is gone.”

His right hand now also has an intention tremor. Although sometimes he must “set something down quickly to avoid calamity,” Edwards wrote in the epilogue to Much Abides that the “tremor and I have an understanding: If it allows me to do anything I want, I won’t freak out over the occasional mishap.”

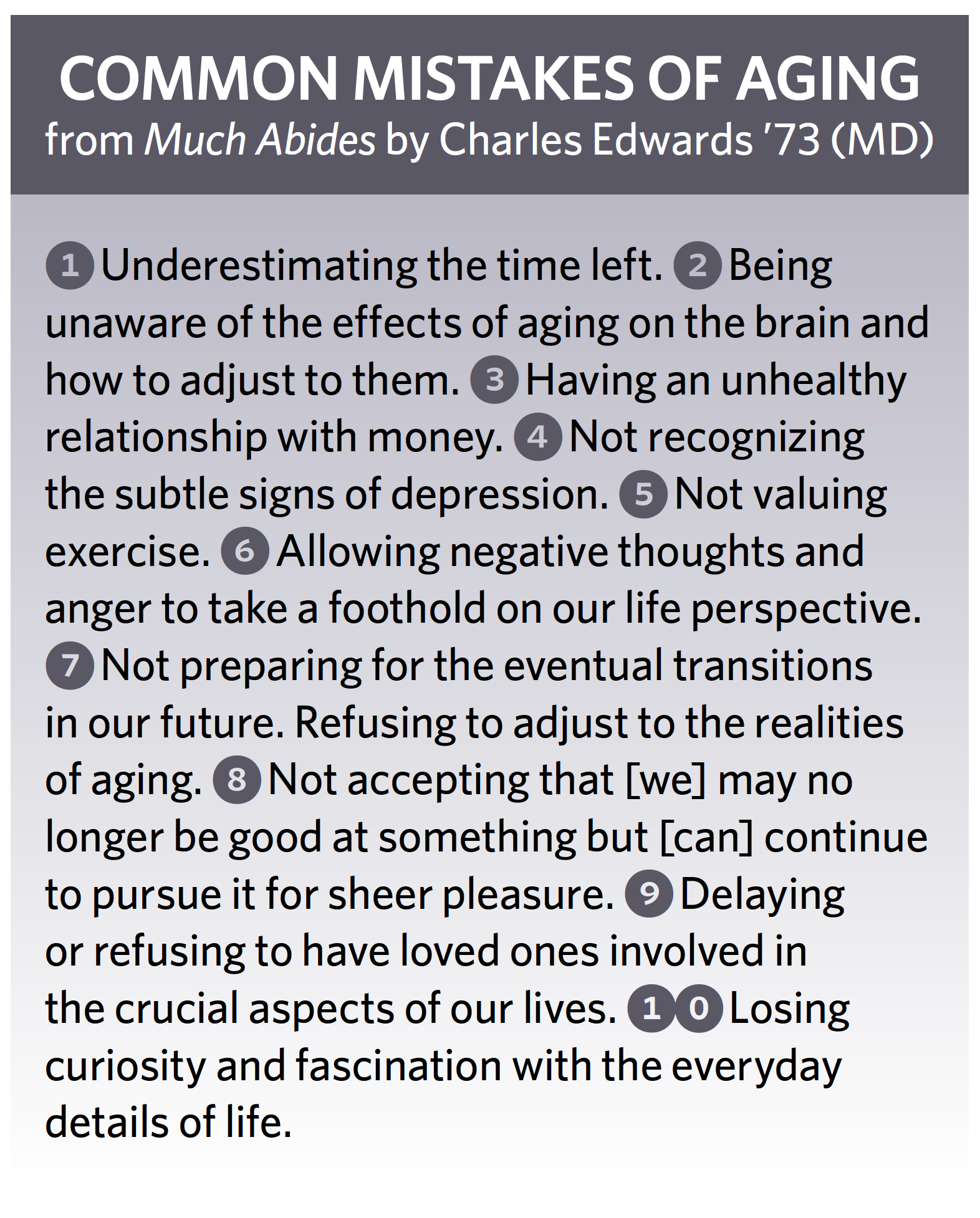

“This late phase [of life] has the potential to provide the most satisfaction and joy for the longest period of time,” Edwards wrote in Much Abides. “There is also the potential for not getting it right. For despair. The questions then arise: How do I avoid that despair and navigate this challenging late stage with balance and insight? How does one not mourn what is lost but make a life out of what is left?”

Every few weeks, someone will call Edwards worried about memory loss. They couldn’t remember a friend’s name. They left the freezer door open.

Edwards can relate.

“I’ve always known every president in order and the dates they were elected,” he said. “My mind works that way. And I couldn’t remember James Buchanan’s name yesterday. I had to remind myself that names don’t matter.”

As he explains in Much Abides, most instances of that kind are the result of normal aging, known in the medical profession as “age-related cognitive decline.” Slow down, Edwards advises. Pay attention. And try not to worry. Anxiety contributes to memory loss.

In the book, he describes the science on aging and its effect on the brain. He suggests ways to prevent memory loss, most importantly by controlling blood pressure and lipids, but also by exercising and being social. He’s puzzled that people prepare for careers but rarely for their retirement years, which can last just as long.

“If valued and approached creatively, this late phase has the potential to provide the most satisfaction and joy for the longest period of time,” he writes. “For all this upside, there is also the potential for not getting it right. For despair. The questions then arise: How do I avoid that despair and navigate this challenging late stage with balance and insight? How does one not mourn what is lost but make a life out of what is left?”

He painted the illustrations that appear throughout his book to make the point that you don’t have to be particularly good at what you do. He enjoys painting but admits he’s not accomplished. “As we age,” he writes, “we must accept that we will no longer always be good at things. Time takes its toll on our talents. What is crucial is doing things that we enjoy and find valuable. If we limit ourselves solely to pursuits that we excel in, we will have lots of free time to mourn the loss of expertise.”

Although he looks younger than his 73 years — his reddish-brown hair is still thick and with little gray — Edwards feels himself slowing down. “I’ve always said I’d like to practice medicine until the day I die, but the closer I get to that, the less practical it becomes,” he said.

Although he looks younger than his 73 years — his reddish-brown hair is still thick and with little gray — Edwards feels himself slowing down. “I’ve always said I’d like to practice medicine until the day I die, but the closer I get to that, the less practical it becomes,” he said.

He has reduced his hours at the clinic to three days a week and plans to retire when he turns 75. But, he said, leaving won’t be easy. The clinic — and, more importantly, the patients and their families — have become a part of his identity. He shares his cell phone number freely, allowing families to call him at all hours with all sorts of problems.

“Once you move into that space in people’s lives where they depend on you, I don’t know how you turn away from that,” he said. “I’m struggling with that.”

Soon, Edwards will have to grapple with the same advice he dispenses in his clinic and in Much Abides, of how to “not mourn what is lost but make a life out of what is left.” He often is asked what he will do after retiring. He enjoys fly-fishing for trout on the Cane River at his farm near Mount Mitchell. He has begun dabbling with writing fiction. And he continues to paint. Will that be enough for a man once consumed by medicine? He doesn’t know yet.

What he does know is that he will end his second career in medicine confident that his work has mattered deeply — to him, and to the people who have walked into his clinic.

“The patients with dementia and the families caring for them,” he wrote, “have shown me the best of what human beings are capable of.”

—Elizabeth Leland ’76 is a freelance writer based in Charlotte.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.