Shades of Gray

Posted on Jan. 14, 2021

Student mental health is a deepening problem. The University is taking a comprehensive approach to help, but its limitations often collide with personal crises.

by Beth McNichol ’95 | Illustrations by Haley Hodges ’19

Jake Lawler ’20 came to UNC in 2017 with a football scholarship, a passion for movies and a talent for writing. A longtime foe followed him there, one that he had known since middle school — when he wore crooked glasses and ill-fitting clothes and was teased for being a mixed-race kid.

“I felt it was my problem to deal with,” he said. “It was my sadness. It was my depression. I got really good at hiding it, at being even more gregarious than necessary just to dissuade any notion that something was wrong.”

No one would ever guess that as a high school sophomore, Lawler had sat on a bucket in his backyard shed with a belt and an intention to kill himself. He told no one: not his friends, not his family. “When you’re depressed,” he later wrote on his blog, “your world operates in shades of gray, and you believe that you’re the reason for it.”

By the time he stood atop Craige Deck in Chapel Hill in January 2019 and considered jumping, he had long felt that he belonged nowhere.

“When you’re depressed, your world operates in shades of gray, and you believe that you’re the reason for it.” —Jake Lawler ’20

“I just didn’t really have a place in the world,” Lawler said. “And I didn’t really know if anyone could help me.”

When Julianna Chalk lost her brother, a UNC-Charlotte freshman, to suicide while she was in high school, the tragedy drove her to a personal reckoning. She saw how the jittery shadows of her life — the sometimes-debilitating, near-constant anxiety she’d felt since she was young — could drive her down a dangerous path. In the months that followed her brother’s death in 2016, she sought help for herself, speaking to a therapist, trying medication and launching a local suicide prevention charity called Walk. Support. Glow.

Despite Chalk’s awareness, her anxiety became worse when she landed in Chapel Hill, wrapping itself around the jagged contours of a new threat: imposter syndrome.

“I came from a really small high school that was a breeze for me,” said Chalk, now a senior. “And when I got here, there were all these people doing all these different things, and I couldn’t keep up with them. They were in five clubs, and I could barely handle one. It can be really hard to keep up with people who are high functioning, with no overwhelming mental health issues. There are parts of you holding you back that are not your fault.”

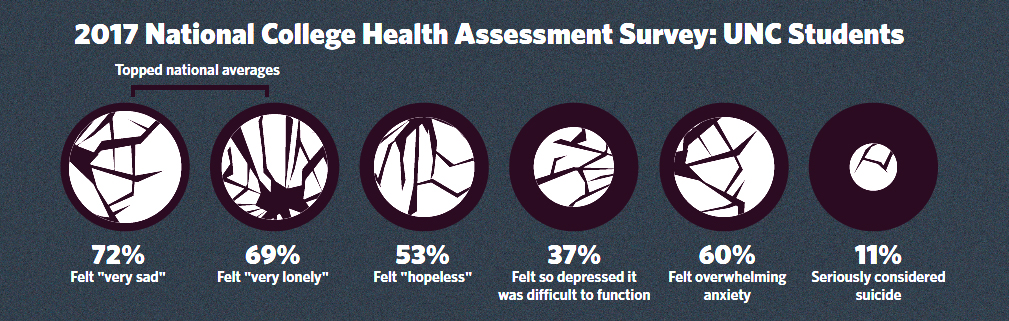

Lawler and Chalk both wrestled with the belonging and identity questions that contributed to a rise in mental health disorders among college students nationwide long before the pandemic struck. Whether driven by academic pressure, marginalization or financial stress, the numbers of Carolina students struggling painted a disturbing picture of pain. A National College Health Assessment Survey in 2017 found that 60 percent of UNC undergraduates felt overwhelming anxiety; 37 percent said they felt so depressed it was difficult to function. They felt “hopeless” (53 percent), “very lonely” (69 percent) and “very sad” (72 percent), topping national averages in the latter two categories. Eleven percent reported having “seriously considered suicide” in the past 12 months. The data were similar for graduate students.

COVID-related stressors now are widening the causes and reach of those struggles, Jane Cooley Fruehwirth, associate professor of economics at Carolina, told a UNC System Board of Governors committee in September. Fruehwirth surveyed all Carolina first-year students in October 2019 and again in February regarding their mental health and found no upward swing in emotional problems. However, a summer survey of the same students — four months into the pandemic — revealed a 40 percent increase in anxiety symptoms and a 48 percent rise in depression. Overall, a quarter of first-years were suffering from anxiety and one-third from depression.

“It can be really hard to keep up with people who are high functioning, with no overwhelming mental health issues. There are parts of you holding you back that are not your fault.” — Julianna Chalk

There was a time when “mental health day” was an excuse to go slack when you were tired of work and wanted a free day off. This spring, students will not have the traditional spring break — due to the danger widespread travel-and-return poses in the pandemic — but instead will get “wellness days” on a Monday and Tuesday in February, a Thursday and Friday in March and a Monday in April.

Social isolation and distance-learning difficulties were strong predictors of emotional suffering, Fruehwirth said. She also found evidence that a higher percentage of students were going untreated.

DeVetta Holman-Copeland ’79 (’85 MPH), resiliency coordinator for UNC Student Wellness, said that mental health disorders commonly appear during the college years. Even as young adults begin to navigate life independently, their brains have not finished developing. That development is like a game of Jenga, she said, a delicate balance of building blocks. The more blocks you remove, the more the tower sways.

“As academicians or staff and administrators, we tend to see this as, ‘Here’s another student that has demonstrated their academic prowess and they’re coming to UNC, and let’s just educate them,’ ” Holman-Copeland said. “But the living and learning that you get outside of the classroom really impacts how well you do in the classroom.”

Filling the holes

The University has begun to reexamine that Jenga tower in earnest, thanks mainly to the insistence of a generation born in the shadows of 9/11 and raised in the anxiety-inducing worlds of social media, overseas wars, school shootings, a recession, racial disparities, yawning socioeconomic and political divisions — and now, a ruthless pandemic.

“I have yet to meet a student in my time at UNC who says they don’t care about mental health,” said Jordan Garrick ’20, former co-chair of the UNC Student Government Mental Health Committee, which launched in 2018. “All of us realize now, with the changing times, that mental health is important.”

“I have yet to meet a student in my time at UNC who says they don’t care about mental health.” — Jordan Garrick ’20

In 2019, the University published a 40-page report with recommendations to tackle the swelling mental health needs on campus. The task force that authored it came to fruition after several students lobbied the administration to act, said Dr. Allen O’Barr ’87 (MD), director of UNC’s Counseling and Psychological Services office.

“The University had known for a long time that we needed to look at the issues comprehensively,” said O’Barr, a psychiatrist. “It was the students coming forward and saying this needed to be done that moved it to the forefront. They have been transformative.”

Students also have been candid about their frustrations — including with O’Barr’s own office. Chalk visited CAPS during her first year at Carolina after an incident with a friend churned up fresh anguish over her brother’s death. She was dismayed when she received a referral for off-campus counseling services.

“They said that their psychologists were reserved for people who are suffering more immediate traumas,” Chalk said. “It was baffling. I’ve been very discouraged to go back.”

The complaint — repeated by many students — is rooted in misperceptions about CAPS’ role and in its limitations as the mental health provider for the University’s 30,000 students. What the office’s 30-person staff can do is short-term one-on-one therapy for an issue resolvable over a semester. What it can’t do: Dig into the underlying traumas that have been building in a student’s psyche over many years.

O’Barr keenly feels the limitation, which psychological offices at large universities nationally share.

“That’s probably our biggest struggle, is explaining the brass tacks of resource limitations to somebody who is struggling emotionally,” O’Barr said. “I hear a lot of feedback that a student will build up the courage to come to CAPS over a number of weeks, then they get referred out and say, ‘Whatever. I just can’t do it.’ That’s really what we don’t want to happen. We don’t want them to suffer.”

About 30 percent of CAPS patients receive referrals to off-campus therapists, which are not covered by student health fees and, if not conducted by telehealth, require personal transportation. Although CAPS coordinators help students connect with local therapists who accept health insurance, both money and access remain significant barriers. Students who have coverage through their families can be reluctant to tell their parents that they need help. Meanwhile, students with financial struggles are among the groups most vulnerable to anxiety and depression.

“It’s an imperfect system,” O’Barr said. “I don’t think there’s any way to provide ongoing long-term psychotherapy for a population of 30,000 people. I can’t even imagine what numbers of counselors that would take. What we find is that every time we add counselors to help with demand, they just get filled up right away.”

“It’s an imperfect system,” O’Barr said. “I don’t think there’s any way to provide ongoing long-term psychotherapy for a population of 30,000 people. I can’t even imagine what numbers of counselors that would take. What we find is that every time we add counselors to help with demand, they just get filled up right away.”

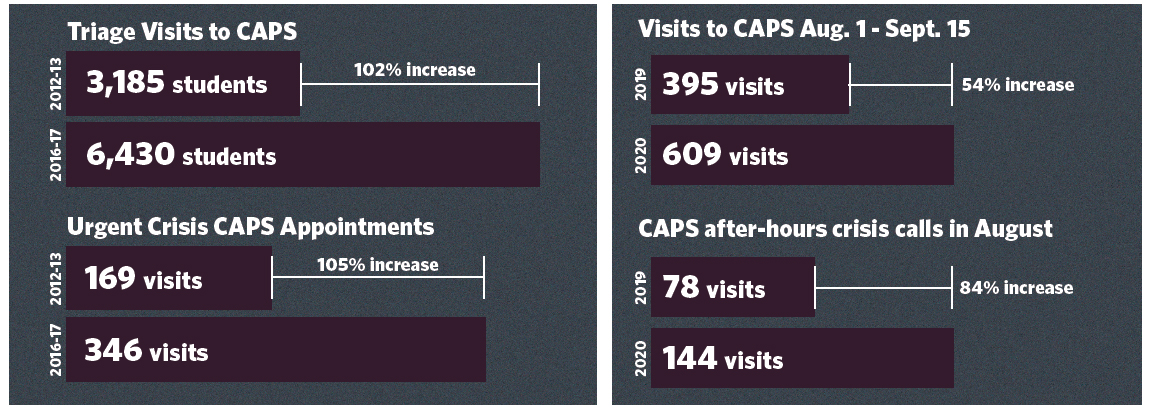

Visits to CAPS, which uses a walk-in triage system to assess each student’s initial need, increased 102 percent over five years, from 3,185 students to 6,430, according to the task force report. Appointments deemed “urgent crisis” grew 105 percent.

Calls to CAPS’ 24/7 hotline, which debuted in fall 2019 in response to task force findings, paralleled the growth of in-person appointments. The service, which is run by a national contractor after 5 p.m., fielded double the expected number of calls in each of its first three months.

The pandemic’s toll was evident at CAPS as students returned to campus in August. From Aug. 1 to Sept. 15, brief therapy visits were up 54 percent compared with the same six-week period a year earlier, and all medication appointments were up 10 percent. In August alone, after-hours crisis calls increased 85 percent from August 2019. O’Barr noted that many students contacted CAPS from campus isolation

or quarantine.

Garrick said members of the student government committee have lobbied for an increase in student health fees to help meet the office’s demand. They also tackled several of the recommendations made by the administrative task force last year. Among the most impactful was Well Ride, a rideshare program that provided Lyft vouchers to the 1,500 students whom CAPS refers to off-campus therapists.

“I don’t think every student understands the financial strain that CAPS is under,” Garrick said. “If they had the staff, they wouldn’t turn any students away.”

O’Barr estimated that CAPS would need a recurring budget increase of about $500,000 to expand its staff to a sustainable level. But he also is realistic. Anything beyond that figure, he said, “would be better used in looking at something to fix upstream,” such as wellness coaches who could head off mental health crises by steering student behavior and thinking in healthy directions.

“We’re all struggling,” he said. “We all need somebody to talk to. That doesn’t necessarily require a counseling degree.”

Lost and overlooked

If the volume of calls to CAPS’ new hotline speaks to the number of students in need, the reasons students dial reveal a collective need for connection. From ending relationships to failing tests, from panic attacks to medication uncertainty — and now, the isolation and fear surrounding COVID-19 — students often are searching for more than a mental health expert. They want an anchor.

“It’s a unique generation,” Jake Lawler said. “We’ve never been so connected globally but disconnected socially. That plays a part in how people are growing up today.”

With COVID-19 prompting remote learning, that feeling of disconnection spawned additional — and sharper — angles. Students who returned home last March and again in the fall struggled not just with uncertainty about the future but from the loss of emerging independence. Back under their families’ roofs, they balanced online classes with household duties; some resumed caregiving roles for grandparents and younger siblings.

Social disengagement has long been a concern at Student Wellness, which has a public health campaign focus but also offers some one-on-one wellness coaching. The latter “could easily take over our office,” said Alicia Freeman, its mental health awareness programs coordinator.

“I’ve heard, and seen, a lot of social isolation and some loneliness,” Freeman said last April. “They just want somebody to talk to.”

The danger arises when that loneliness imprints on their psyches like a branding iron. Before the campus moved to online classes in March, Chalk spoke of fellow students so stung by anxiety and depression that they struggled to get up in the morning. The more they retreated, the more their instructors and fellow students dismissed them as lazy — and the more shame they felt.

“Everyone at UNC is talented and accomplished,” said Chalk, who expanded her Currituck County suicide prevention group, Walk. Support. Glow., as a student organization at Carolina. “We’re supposed to be held in high esteem, and it can cause a lot of people to fight alone.”

Holman-Copeland said that when students struggle emotionally, the antidote is “belonging and mattering.” That can be especially true for low-income or first-generation students and students of color.

“Their mental health is being driven by, ‘Should I be here?’ ” said Holman-Copeland, who continued to meet with students via Zoom after in-person classes were canceled last spring. “And that’s where depression sets in. The weight of the world and the weight of the University plus isolation gives you a depressed state of mind, which impacts mental health.”

As George Floyd’s killing sparked Black Lives Matter protests across the country, Holman-Copeland said Black students were experiencing twin pandemics, or “COVID-1619” — a reference to the year the first ship carrying enslaved Africans arrived in Virginia. That additional emotional burden pushed an alarming number of first-year Black students at Carolina to higher rates of depression, according to Fruehwirth, the economics professor. While 32 percent of first-year students overall reported depression symptoms, 61 percent of Black students did — a staggering increase of 90 percent during the first four months of the pandemic.

“I don’t think every student understands the financial strain that CAPS is under,” Garrick said. “If they had the staff, they wouldn’t turn any students away.” O’Barr estimated that CAPS would need a recurring budget increase of about $500,000 to expand its staff to a sustainable level.

Carolina is not exceptional in its need to better address the mental health crises of minority students. However, the University is undergoing an overdue examination of racist figures and symbols from its past. The handling of those symbols has roiled the problems of identity and belonging and led to significant anxiety for Black students at UNC.

“To encounter the mental health challenges which are typical for any student going through life changes, and then to deal with a university system that was willing to build what felt like a shrine to Silent Sam on South Campus, where tons of Black students live … it was like a slap in the face,” Garrick said last spring. “I don’t talk about it a lot, but it’s hard to get up in the morning and try to be a change agent and leader at a place where the administration doesn’t even seem like they care about me.

“The experience made me realize that a lot of times, minority groups on campus are expected to figure it out on their own.”

Garrick stumbled across Sister Talk, one of Holman-Copeland’s weekly support groups in Student Wellness, as UNC debated moving the felled Confederate statue to a proposed museum near the former Odum Village. But given the strains for minority students—who battle not just family and societal expectations but the anxiety of marginalization — Garrick wondered why she had to rely on word-of-mouth to find Sister Talk.

“I can only imagine how Black women, brown women, Black men, brown men, would feel if these initiatives were coming from the top of the University,” Garrick said. “That would really communicate something even more than just my peers working tirelessly to support me. I can only imagine how many students of color that the University would be able to retain — and how it would make the students that have spent four years here feel.”

Sister Talk continued, virtual but uninterrupted, throughout 2020, said Holman-Copeland. Indeed, for both Holman-Copeland and O’Barr, summer break passed without distinction from the spring semester; the demand for their services kept climbing. As it did, O’Barr saw an opportunity to nudge forward his own department’s response to the needs of Black students despite CAPS’ hamstrung budget. He requested — and the University granted — access to a limited reserve fund to hire four Black counselors, forming CAPS’ Multicultural Health Program under the direction of two of its Black staff psychologists.

“Underrepresented students have been underserved, historically, in mental health,” O’Barr said. “Part of that is because they don’t feel comfortable, don’t see anyone who looks like them. If you’re feeling vulnerable — and especially if you’re feeling vulnerable about race — what’s it like to come in to talk to a white therapist? How do you know that person is safe?”

But there’s a catch: The four therapists, who began in August, are on a temporary, one-year assignment. Whether they remain depends on CAPS receiving that long-sought-after increase in its permanent budget. Given the new therapists’ constant demand, O’Barr hopes University purse-holders will take notice.

“Daily, I get emails asking for the Multicultural Health Program,” O’Barr said. “It was a needed move.”

Combatting stigma

Even where the right mental health resources exist, however, shame continues to prevent some college students from seeking help. In January 2019, talking about his depression was the last thing that Jake Lawler wanted to do. The burden on others was too immense, he thought; the stigma for himself too great.

“I’m in the Bermuda Triangle of terror,” Lawler said. “I’m a man, I’m a Black man, and I’m an athlete. All of those things are like, ‘No, no … and hell, no. Don’t say anything. Don’t talk about it.’ ”

Instead, he spent many days and nights going on long walks alone. On one of those evenings, two weeks after he posted his first short story on his blog, he stood at the top of Craige Deck and dared the troubled corners of his mind to take flight.

“I had thought that publishing my short story would just kind of be the movie ending,” Lawler said. “It would be a cure-all. I thought, ‘Maybe if I get this out there, I’ll stop feeling this way.’ And I didn’t. That’s the part that really terrified me. I realized that I’ll probably always feel like this.”

Lawler said he can’t explain why he didn’t jump that night; some unseen force intervened. But later, when his roommate, senior running back Michael Carter, asked him where he was headed on all those walks, Lawler finally broke his silence. He shared how he felt with his parents and his friends. And in June 2019, he wrote a stirring public blog post that detailed his long history with depression.

Telling people transformed Lawler’s life.

“Throughout high school and college, I thought about killing myself at least once a day — and since I posted that, I haven’t thought about it once,” said Lawler, who since has heard from countless others who are suffering or have lost someone to mental illness. “It was like the crushing weight had been lifted. There are people who are willing to carry it with me, and there’s no better feeling than that.”

Dwight Hollier ’91, the senior associate athletics director for athletes’ health and well-being, was among those who helped lift the weight. Hollier once had been in Lawler’s shoes. After leaving the NFL in 2000 — with a master’s degree in mental health counseling that he had earned while playing for the Miami Dolphins — he fell into a deep depression that took years to shake.

“All that can be exacerbated in a college environment, where working really hard is both the norm and celebrated. The lingering question is: Where does that end, and where do you find balance in other areas of your life?” — Nikhil Rao

“The reality is that we don’t need to be tough,” said Hollier, who struggled with his post-football identity. “It’s OK to have feelings and to feel pain and to address it. It becomes a challenge when you don’t.”

But stigma can be tricky: It also can persist when students encourage their friends’ mental health but ignore their own, said senior Nikhil Rao, former co-chair of Student Government’s mental health committee.

“There’s still an underlying disregard for mental health reflected in students’ actions,” Rao said. “All that can be exacerbated in a college environment, where working really hard is both the norm and celebrated. The lingering question is: Where does that end, and where do you find balance in other areas of your life?”

Rao created the UNC Peer Support Network to address that problem, a one-hour weekly meeting run by School of Social Work-trained facilitators that gives stressed-out students a place to decompress. Like more tailored support groups on campus run by CAPS and Student Wellness, the network is an alternative to CAPS for students who don’t necessarily need counseling.

“Peer-to-peer communication is extremely powerful,” Hollier said. “These stories are important. It’s important that we talk about mental health, that we share our experiences and our scars, and let people know that it’s OK to reach out.”

Lawler, who graduated in May and moved to Los Angeles to pursue screenwriting, also shared his story during a TED Talk-style presentation to other athletes and continues to speak publicly about his struggles. Chalk, too, said she doesn’t shy away from talking about her brother’s suicide or her own issues with mental health.

“I want people to be able to look at their peers and know when to ask, ‘Is something going on?’ ” said Chalk, who has given presentations to fraternities. “I want people to not be scared to have that conversation.”

That conversation is more relevant now than ever — and given students’ isolation, access to it has become more complicated. But Holman-Copeland said the University has to continue to guide its student body through current sorrows, to strengthen the Jenga tower, to lay on more blocks.

“Students are having to dig deep,” she said, “and with the help of everyone on campus, all the staff, including myself, this is where we have to heighten our resources, our skills, our levels of thinking, and help students be the best that they can be.”

Beth McNichol ’95, a freelance writer based in Raleigh, is a former associate editor for the Review.