The Fierce Urgency of Now

Posted on Jan. 14, 2021

(Illustration by Jason Smith ’94)

Silent Sam, Charleston, Charlottesville and George Floyd made the headlines. On a less visible but equally impassioned front, faculty of color at Chapel Hill believe this is the moment for action toward equity.

by Barry Yeoman

Kia Caldwell woke up June 18 with the news heavy on her mind.

For months it had been dominated by a single headline: the COVID-19 pandemic, which in the U.S. has blazed most mercilessly through communities of color. Then, in late May, came George Floyd’s asphyxiation under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer. The video of Floyd, calling out for his late mother, pierced the national conscience and highlighted the ever-lengthening list of Black Americans killed by white authorities and civilians.

Demonstrators had gathered in more than 2,000 cities and towns. They hoisted signs and blocked roadways and dodged tear gas and rubber bullets. Their message spread beyond the streets as education, business and political leaders vowed to work against racism in their own domains.

Kia Caldwell: “A historic social uprising for racial justice was taking place. As an academic, I felt that my university also needed to be part of the reckoning.” (UNC/Megan May)

For Caldwell, a professor of African, African American and diaspora studies, the national news was inseparable from events at Carolina.

In 2019, she and 13 colleagues had written a memo describing “the rapidly declining racial climate at the University.” Morale, they wrote, runs low among Black and brown faculty, who are underrepresented in proportion to the state’s population. Some have left for other schools in what Jennifer Ho, a former UNC professor of English and comparative literature, described in an interview as “a kind of indictment and a statement.”

Many of those who remain say they face work demands related to race that their white counterparts don’t — tending to the well-being of students of color and ensuring diverse voices at a cascading series of tables. “Every committee they need a Black face on, you get contacted to be that person,” says James H. Johnson Jr., the William R. Kenan Jr. Distinguished Professor of strategy and entrepreneurship at Kenan-Flagler Business School.

Several professors, including Caldwell, had met twice with administrators in 2019 to discuss the campus climate and develop policy solutions. An overlapping group had met regularly with Provost Robert Blouin to offer advice on “Carolina Next: Innovations for Public Good,” UNC’s comprehensive strategic plan that has as its first objective “Build Our Community Together,” focused on “creating a more diverse, equitable and inclusive community.”

The advisory conversations broke down in December 2019, after the UNC System’s Board of Governors voted to give $2.5 million to the Sons of Confederate Veterans to maintain the Confederate memorial, Silent Sam, which protesters had toppled in August 2018.

In 2019, Kia Caldwell and 13 colleagues wrote a memo describing “the rapidly declining racial climate at the University.” Morale, they wrote, runs low among Black and brown faculty, who are underrepresented in proportion to the state’s population. “We invite the University leadership and our faculty colleagues to stand and work with us,” Caldwell said.

That June morning, Caldwell also woke up thinking about the University’s “Roadmap for Fall 2020,” the plan for the return of most students, faculty and staff to campus amid the pandemic. She worried that students and faculty of color, who faced outsized health risks, were excluded from the formal decision-making process.

For Caldwell, all these elements felt connected. “A historic social uprising for racial justice was taking place,” she said. “As an academic, I felt that my university also needed to be part of the reckoning.” So she sat down in her home office. She opened Google Docs. And she started writing.

Four days later, after her peers had offered edits and additions, Caldwell released the document. Called the Roadmap for Racial Equity, it proposed a three-year, 13-part plan to diversify the faculty and administration and address racial bias. “We invite the University leadership and our faculty colleagues to stand and work with us,” said the preamble, “to make UNC-Chapel Hill a more equitable and inclusive campus, where all can succeed and thrive.”

The 35 original signatories encouraged others to co-sign. And they did — more than 1,200 faculty members, students, staff and alumni.

Carolina’s administrators say they agree with the sentiments behind the Roadmap for Racial Equity and intend to dissect the University in search of the causes of these disparities. “It’s not until we actually get at the root [that] we can really begin to reverse-engineer this institution to eliminate all traces of structural systemic racism,” said Blouin, who also is executive vice chancellor.

Miguel La Serna and others say it will take an ambitious, well-funded, collaborative effort to craft an institution that reflects the diversity of 21st-century America. (Contributed photo)

Some faculty of color say they see goodwill on the part of campus leaders. “We had a meeting with the administration,” said Miguel La Serna, a professor of history. “They actually were saying that they felt like they can get on board with a lot of these things and that they would be happy to work with us toward implementing them. So that was a really encouraging sign.”

But La Serna, Caldwell and others add that intentions aren’t enough. It will take an ambitious, well-funded, collaborative effort, they say — an effort central to Carolina’s mission — to craft an institution that reflects the diversity of 21st-century America.

An agonizing history

Academia can be a rough place for what scholars call BIPOC faculty — Black, Indigenous and other people of color. U.S. campuses have been plagued by reports of hostile work environments and lackluster diversity efforts.

“The widespread claims that higher education is objective, meritocratic, and color blind, providing equity for all, do not hold up,” sociologist Ruth Enid Zambrana wrote in her 2018 book Toxic Ivory Towers. Underrepresented minorities are “expected to publish more, teach more, and serve more to progress at the same pace” as their white peers.

“The widespread claims that higher education is objective, meritocratic, and color blind, providing equity for all, do not hold up,” sociologist Ruth Enid Zambrana wrote in her 2018 book Toxic Ivory Towers. Underrepresented minorities are “expected to publish more, teach more, and serve more to progress at the same pace” as their white peers.

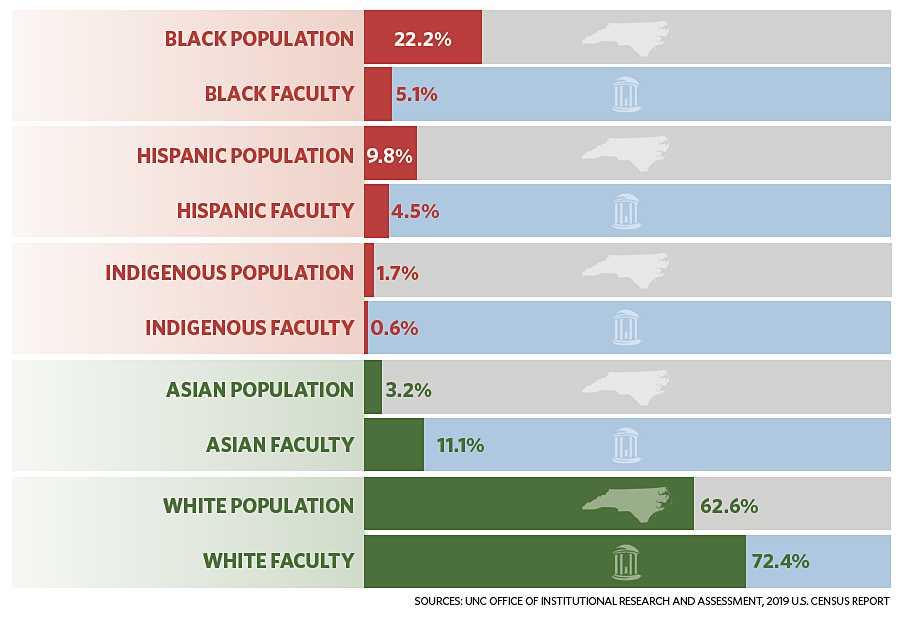

The numbers at UNC mirror the national trend. Blacks make up 22.2 percent of the state’s population but 5.1 percent of the faculty, according to 2018 figures from the University’s Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. Hispanics make up 9.8 percent of the population and 4.5 percent of the faculty. Indigenous people make up 1.7 percent of the population and 0.6 percent of the faculty.

The overall student makeup, based on spring 2020 numbers from the same office, is 8 percent Black, 7.8 percent Hispanic and 0.5 percent Indigenous.

But Carolina has a distinct story, too, which dates to its 18th-century founding. Enslaved people helped build the campus, and the University’s first Board of Trustees consisted overwhelmingly of slaveholders. Slavery funded the University, too. “Human beings were often sold along with real estate by university attorneys, who received a commission on the sale and turned the profits over to the treasurer of the Board of Trustees,” notes the University Archives at Wilson Library. Some students brought enslaved servants to class.

That history can feel close. “My grandmother was born in 1928. She’s still alive,” said Ronald Williams II, an assistant professor of African, African American and diaspora studies. “She could not vote for many years. She’s a Black woman born into poverty in the American South. So I’m very much connected to a family of people whose lives and livelihoods were defined by the material and psychological legacy of American slavery.”

Ronald Williams II suggests “decolonizing” the curriculum by requiring students to study African American, Asian American, Latinx and Native American history. Such a mandate would produce better-informed students and could draw more BIPOC faculty, Williams said. (UNC/Dan Sears ’74)

Many campus buildings memorialize slaveholders and white supremacists. In 2015, Saunders Hall, named for Ku Klux Klan leader William L. Saunders (class of 1854), was renamed Carolina Hall after years of student agitation. (The Board of Trustees rejected students’ call to rename it after Black anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston.) Last year, four more buildings had their names removed. Three more are awaiting decisions by Chancellor Kevin Guskiewicz and then the trustees. Dozens of others are up for similar consideration.

The “Memorial” in Kenan Memorial Stadium has been removed, its original namesake, William Rand Kenan Sr. (class of 1864), having commanded a paramilitary force that helped overthrow Wilmington’s biracial government in an 1898 massacre. The University decided in 2018 to designate the stadium’s name for his son, William R. Kenan Jr. (class of 1894), who provided most of the money to build the stadium and had dedicated it to his parents in 1927.

“The commemorative landscape is not neutral here,” said historian Malinda Maynor Lowery ’02 (MA, ’05 PhD), director of the University’s Center for the Study of the American South. “You have a belief on the part of the decision-makers that that commemorative landscape is wallpaper, that it doesn’t truly reflect anything about who we are now. And I think what students and faculty have been saying is that these are not tokens of memory. … Those points on the landscape provide us with orientation in how we conduct ourselves on a day-to-day level.”

Until two years ago, the centerpiece of Carolina’s commemorative landscape was Silent Sam, erected when Confederate statues were designed to intimidate Blacks and reinforce segregation. During its 1913 dedication, industrialist Julian Carr (class of 1866) recalled having “horsewhipped a negro wench until her skirts hung in shreds” because she “maligned a Southern lady.” Carr, who had leadership roles in the GAA and served as the association’s president from 1912 to 1917, added that “the purest strain of the Anglo Saxon is to be found in the 13 Southern states — Praise God.”

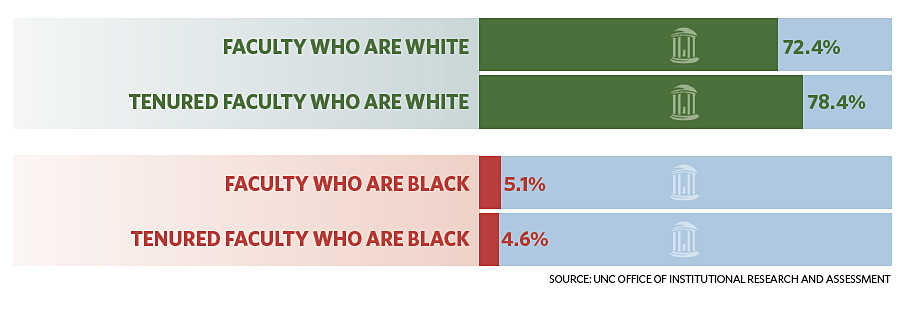

For BIPOC scholars, at Carolina and elsewhere, the extra workload takes away time from scholarly writing, making it harder to earn tenure. And Carolina’s tenured faculty are less diverse than the University’s overall faculty.

Members of the campus and Chapel Hill community had protested Silent Sam since the 1960s, and in recent years clashed with monument defenders.

“Campus is where students live,” said Caldwell. “So basically, this was their home environment that was being filled with hate and danger.”

Even after the statue’s toppling in 2018, the Silent Sam issue didn’t disappear. The UNC System Board of Governors brokered a deal with Sons of Confederate Veterans — a group that promotes a message, repudiated by mainstream historians, that the Civil War was not about slavery and that has documented alliances with white-supremacist groups. The Chapel Hill campus was told to make up to $2.5 million available for costs associated with moving and displaying the monument.

BIPOC faculty call the settlement with the SCV, which a judge later voided, a demoralizing blow.

“That $2.5 million deal was an atrocity,” said Sharon P. Holland, chair of the department of American studies. “Why in the world would you think that a Black faculty member would not be pissed off about that?”

Provost Robert Blouin: “It’s not until we actually get at the root [that] we can really begin to reverse-engineer this institution to eliminate all traces of structural systemic racism.” (UNC)

At the time, then-Interim Chancellor Guskiewicz wrote a letter to the Board of Governors noting the “concerns and opposition from many corners of our campus.” Faculty wanted to see more outrage. “We were really hoping for a written condemnation of the Sons of the Confederacy or [of] the settlement,” La Serna said. “And we got neither.”

Tenure is tougher

La Serna, who is Peruvian American, grew up in a working-class neighborhood in Sacramento “where police car chases ended up literally in my backyard, with people jumping my fence and helicopters overhead,” he said. Education was his “escape hatch.” After earning a history doctorate in 2008, he came to Chapel Hill as part of the Carolina Postdoctoral Program for Faculty Diversity.

“It was a tremendous opportunity for me to get my foot in the door,” he said. The program develops scholars in the hopes of preparing them for tenure-track appointments at UNC and elsewhere. “And that ended up working out.”

In addition to his scholarship on 20th-century Latin America, La Serna turned his attention to making Carolina a more inclusive campus. It’s “physically exhausting, emotionally draining” work, he said, that doesn’t always pay concrete dividends. “Everybody agrees with these things in principle. But in practice, it’s a lot easier to say, ‘Here’s why we can’t do that.’ ”

In 2017, for example, La Serna and some colleagues began talking about the growing number of Indigenous studies scholars who have raised Carolina’s profile in the field. “If we could find a way to create a cluster hire and bring in two or three people who work on different areas of Indigenous studies, we could actually be the leader in the world,” he said. “Cluster hiring” involves recruiting multiple scholars to work on a shared research interest, often in different departments.

The professors met with campus leaders in 2018. “And we were told, ‘That sounds great. We support that.’ ” But the moral support did not translate into funding.

Jim Johnson talks about “race fatigue”: the experience of repeatedly serving on personnel committees only to see Black scholars funneled into non-tenure-track positions or a Black colleague’s research dismissed as “ghetto sociology.” (Grant Halverson ’93)

The exhaustion theme permeates many conversations with faculty of color. “I probably ran myself ragged the first five, six years I was here,” said Erika K. Wilson, an associate professor of law. Because Black faculty have no room to be “anything less than excellent,” she said, “I was waking up at 4 in the morning to get some time to write, to prepare for class, and trying to make 24 hours be 30 hours in a day.”

Johnson, the business professor, described Wilson’s schedule as “the norm.” Until the pandemic, he arrived at his office at 6 every morning, part of a decadeslong strategy to maintain the competitive edge that Black academics need. “You have to be prepared to stay up all night to kick somebody’s butt tomorrow morning,” he said. “You can never take a day off.”

Even that might not be enough. Johnson talks about “race fatigue”: the experience of repeatedly serving on personnel committees only to see Black scholars funneled into non-tenure-track positions or a Black colleague’s research dismissed as “ghetto sociology.”

Others have described a similar futility. “Whenever I would go to these meetings where faculty would voice their concerns, I left with the feeling that it was always an excuse,” said Enrique W. Neblett Jr., a former UNC professor of psychology and neuroscience who is considered one of the leading U.S. scholars in the area of racism and health. “The impression was, well, if you look at our peer institutions, we’re doing quite well.” Neblett, who is Black, said he left UNC in 2019 primarily because his wife’s soft-money position had ended. One reason the couple took jobs at the University of Michigan, he added, was its national leadership on diversity issues.

Erika K. Wilson: Because Black faculty have no room to be “anything less than excellent … I probably ran myself ragged the first five, six years I was here.” (Grant Halverson ’93)

For BIPOC scholars, at Carolina and elsewhere, the extra workload takes away time from scholarly writing, making it harder to earn tenure. “The fact that we’re doing a lot of service and mentoring and student support is not taken into account,” Caldwell said.

Carolina’s tenured faculty are less diverse than the University’s overall faculty. Based on 2018 numbers, whites represent 72.4 percent of all faculty and 78.4 percent of tenured professors. As noted earlier, Blacks represent 5.1 percent of all faculty; they account for 4.6 percent of tenured professors. The trend is similar for other faculty of color, who overall have made modest gains during the past decade.

Sibby Anderson-Thompkins ’87 (’90 MA), the University’s interim chief diversity officer, acknowledged that this extra work benefits Carolina while leaving BIPOC professors “vulnerable when they’re going up for tenure.” She said the University leadership wants to correct this.

“We are looking at ensuring that research that is done on diversity-related issues is also valued in the same ways that other types of research are valued,” said Anderson-Thompkins. “These are key areas that we think will support the recommendations coming from the faculty of color: looking at our tenure-promotion policies; ensuring that the contributions of faculty of color are weighted in the same ways that other types of service or leadership has been valued; ensuring that research related to these areas are valued; and that, ultimately, if faculty are taking on additional work, it is with compensation.”

‘Fierce urgency of now’

Carolina’s leaders have pledged to address race more forthrightly. The University’s top leaders focused on the issue during their last two annual retreats, and for the 2019 retreat they all read Toxic Ivory Towers. Individual schools have launched initiatives, too. In June, for example, the law school earmarked $1 million to improve diversity, and in September it announced the hires of two Black professors, Ifeoma Ajunwa and Osamudia James.

In January 2020, after his chancellor appointment was made permanent, Guskiewicz convened a 15-member commission to reckon with the University’s history of complicity with slavery and white supremacy. Guskiewicz said the commission “will include academic initiatives to strengthen our research and teaching, help us to study our past and learn from that past, build from that past and move forward together as a community.” The University, he said, must “build our community together — diversity and inclusion must be a priority, and we must ensure that every person on our campus feels safe, welcome and included.”

After George Floyd’s killing, the commission condemned “the deeper structures of white supremacy and racial injustice that set the conditions for such acts of violence. We recognize that those same structures perpetuate inequities on our campus and in the broader community in which UNC is situated.” Its leaders quoted Martin Luther King Jr. from 1967, as he sought to rally people of conscience against the entangled evils of racism, poverty and militarism. King, they said, “urged the nation to confront the ‘fierce urgency of now.’ ”

“We must move past indecision to action,” King had warned. “If we do not act, we shall surely be dragged down into the long, dark and shameful corridors of time reserved for those who possess power without compassion, might without morality, and strength without sight.”

Interim Chief Diversity Officer Sibby Anderson-Thompkins ’87 (’90 MA): “These faculty have given so much. They’re tired of saying the same thing over and over. They’ve been waiting for change. And I think we have to acknowledge that we’ve let them down and that there’s been a betrayal.” Anderson-Thompkins also is special adviser to the provost and chancellor for equity and inclusion. (UNC/Jon Gardiner ’98)

The work ahead for UNC, the commission noted, “will be painful and unsettling; it will require unflinching honesty in acknowledging long-silenced truths. But what other way is there to redress inequity and to fulfill our responsibility as the ‘people’s university’? ”

At the center of these efforts is Anderson-Thompkins, who also is the special adviser to the provost and chancellor for equity and inclusion.

She grew up in Pitt County, two hours east of Chapel Hill, with a father and grandfather who served as principals of the same all-Black school. Two older siblings desegregated the local public schools. Arriving at Carolina as an undergraduate in 1983, she immediately hopped on a D.C.-bound bus to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the March on Washington.

“That set me on a course,” she said, “to advocate for social justice and to fight for African American students.” She later became president of Carolina’s Black Student Movement. She marched against South African apartheid and fought for the creation of what’s now the Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History.

In 2007, Anderson-Thompkins returned to UNC as an administrator. For eight years, she has run the Carolina Postdoctoral Program for Faculty Diversity, the nationally acclaimed program that helped launch La Serna’s career. She saw how many knowledgeable, committed colleagues were working against racism. “However, their work wasn’t really connected to leadership and the accountability needed from leadership.”

Without accountability, she said, “we really haven’t been able to move the needle.” BIPOC faculty, locked out of certain professional networks, have watched their white colleagues enjoy “an express lane to promotions and opportunities.” The University Office for Diversity and Inclusion, for which she works, lost positions. The interim job she’s now filling was vacant for a year.

The postdoctoral program Anderson-Thompkins runs, which has brought 64 scholars onto the faculty over its 36-year history, has seen 21 of them leave for other opportunities, she said. Three have left in the past two years.

Overall, 29 tenured and tenure-track faculty left to take jobs at other universities between 2018 and 2020, according to Executive Vice Provost Ronald Strauss. Black and Latinx professors, who make up 9.7 percent of that faculty group, accounted for 20.7 percent of the departures. Strauss said faculty leave for a variety of reasons: lucrative offers, UNC’s pay scale, family situations and sometimes the racial climate.

Overall, 29 tenured and tenure-track faculty left to take jobs at other universities between 2018 and 2020, according to Executive Vice Provost Ronald Strauss. Black and Latinx professors, who make up 9.7 percent of that faculty group, accounted for 20.7 percent of the departures. Strauss said faculty leave for a variety of reasons: lucrative offers, UNC’s pay scale, family situations and sometimes the racial climate.

And even some of those who disliked the racial atmosphere had additional circumstances.

Jennifer Ho left for a leadership position she didn’t see coming at UNC. She is now a professor of Asian American studies and director of the Center for Humanities and the Arts at the University of Colorado. She left after not getting a finalist interview for the directorship of the Institute for the Arts and Humanities, where she was associate director.

“The institute’s been around for over 30 years and has only ever had white male directors,” she said. She said she “talked to various mentors who have told me they don’t see a path towards leadership for me at UNC-Chapel Hill, and that if I wanted to pursue leadership opportunities, I would have to leave.”

She believes one obstacle to advancement was her outspokenness about racism at Carolina. “I don’t have any hard evidence, but I’m pretty good at doing textual explication and interpretation. And it’s really hard for me to think that there’s a different interpretation.”

As a Black woman watching these fits and starts, and as a faculty member, Anderson-Thompkins understands the frustration of BIPOC professors. “These faculty have given so much,” she said. “They’re tired of saying the same thing over and over. They’ve been waiting for change. And I think we have to acknowledge that we’ve let them down and that there’s been a betrayal.”

Still, Anderson-Thompkins said she sees a growing commitment from senior leadership. One example is Carolina’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Council, which kicked off in May with leaders from various schools and offices; Tanea Pettis ’95, the GAA’s assistant director of enrichment programs, is a council member representing the GAA. Anderson-Thompkins co-chairs the council. Caldwell represents BIPOC faculty.

“These are key areas that we think will support the recommendations coming from the faculty of color: looking at our tenure-promotion policies; ensuring that the contributions of faculty of color are weighted in the same ways that other types of service or leadership has been valued; ensuring that research related to these areas are valued; and that, ultimately, if faculty are taking on additional work, it is with compensation.”

— Sibby Anderson-Thompkins ’87 (’90 MA)

“By designating someone on the senior leadership team who’s sitting in on those meetings, who’s compensated for this, and who has demonstrated knowledge and expertise within their school, it really elevates the work,” said Anderson-Thompkins. Among the council’s plans is to gather data on faculty compensation, retention and promotion, and then to use that data. “We are now trying to focus on real policy change, systemic change, deep structural change,” she said.

Anderson-Thompkins has suggested embedding a “racial equity lens,” which examines whether policy changes widen or narrow disparities, “across the University.” Her own experience suggests that lens remains elusive. She originally was omitted from the team planning for the fall 2020 return to campus. In a July letter, she and council co-chair Gretchen Bellamy rebuked the University for excluding them and for not considering how the most vulnerable faculty, students and staff would be affected by returning to in-person instruction during a pandemic.

“What we have said has gone wholly ignored,” they wrote. “Simply put, there has been a failure in the process of determining the best path forward for the University because there was no consideration of the equity lens until the last minute, indicating such a point of view is an afterthought.”

Anderson-Thompkins notes that Provost Blouin and the team had requested her feedback.

Blouin said the University’s leaders learned from the criticism. He added Anderson-Thompkins to the planning team. And in September, Guskiewicz named a committee of faculty, students, staff and local residents to advise on spring 2021 planning.

The ambitious roadmap

One of the key goals of last June’s Racial Roadmap is a diversified faculty with deeper expertise in racial equity and social justice. The document proposed 30 new tenure-track positions, plus a substantial funding increase for the postdoctoral program and a revamped process of selecting distinguished professors.

Arts and Sciences Dean Terry Ellen Rhodes ’78: “I think we’ve done some good things in the College and the University. But good grief. When you talk about Silent Sam, and just our past and what we have to confront, we really have so, so much work to do.” (UNC/Johnny Andrews ’97)

Campus leaders called the roadmap a spur to action. “I think we’ve done some good things in the College and the University,” said Terry Ellen Rhodes ’78, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. “But good grief. When you talk about Silent Sam, and just our past and what we have to confront, we really have so, so much work to do.” Since 2019, Rhodes has launched initiatives including “Reckoning,” an educational program focused on history, racial justice and reconciliation. The roadmap helped convince her “that a priority for us [is] to do something about the hiring.”

Rhodes’ first efforts to implement some of the proposals show how fraught these conversations can be.

When Rhodes read the document, she “jumped right away” on one of its proposals. She announced plans to hire a cluster of six professors, in different departments, who study two broad fields. The first is Black and Indigenous families and communities. The second is health, wellness and health equity in communities of color. The searches are still in progress.

“We need to make sure we’re moving the needle more quickly than we have been,” Rhodes said. Not only will the hires advance racial equity, she said, but they also will respond to the academic needs of various departments.

Caldwell, the roadmap’s original author, was surprised to learn from her colleagues about the planned hires. To her, white administrators were moving too quickly and without the type of collaboration she had envisioned.

“It’s a little odd that people would see this Roadmap for Racial Equity, and then just start acting on it without talking to the people who designed it,” she said. “Cluster hires need to be really well-conceptualized to be successful, because cluster hires can fail.” Caldwell wanted to see the process slowed down. She wanted BIPOC faculty to help decide which departments got the hires. She wanted to see efforts to improve the racial climate so the new hires will feel happy and supported and stay.

Caldwell believes the dean was well-intentioned in moving quickly. Still, she asked, “What does that say about the level of disrespect and disregard for the people who designed [the Roadmap]?”

The criticism stung Rhodes. “When I heard that people felt left out, that pained me,” the dean said. She said she had been looking into similar hires even before the roadmap and had consulted, sometimes informally, with BIPOC faculty. She described her choices as tricky: She wants to be inclusive but also must balance budgets, enrollments and hiring requests across 45 departments. “I know the cry is ‘a seat at the table,’ ” she said. “And I do understand that — when that can make sense.”

To Caldwell, the cluster-hire process illustrates what she calls UNC’s top-down governance model. She and many colleagues favor more shared governance. “It’s not just that we need faculty of color at the same old table, doing the same old thing,” she said. “We need a new table.”

Altering structure

The phrase “structural racism” can be intimidating, so it helps to break it down. Think of an actual structure like a house. It can be built. It can be restored, modernized or expanded. When it no longer serves its function, or if it’s dangerous beyond repair, it can be demolished. Even if it looks solid, it’s wise to hire an inspector occasionally to make sure there are no lurking hazards.

Likewise, a university’s bureaucratic, governance and personnel structures can be inspected, modernized or replaced. One way to inspect these structures is through that equity lens: Do they close or widen disparities?

A key structure is the University Office for Diversity and Inclusion, which is smaller than in the past. “Whenever there are gaps institutionally, people who care tend to step up,” Caldwell said. “But we also have become very burned out.” The roadmap calls for “robust funding and staffing” of the administration’s efforts, including two faculty fellowships that focus on equity and inclusion.

Anderson-Thompkins noted one step in that direction. She has secured authorization, and started searching, for a new director of education, engagement and belonging. “We are in a rebuilding stage,” she said.

Another structure is curriculum. Here, UNC can address its own history, and the nation’s history, while also preparing students to live in a country projected to become “majority minority” in 2045. Ronald Williams II suggests “decolonizing” the curriculum by requiring all students to study African American, Asian American, Latinx and Native American history. These do not have to be full-credit courses, he said.

Adding such a mandate wouldn’t just produce better-informed students, Williams said. It also would draw more BIPOC professors. “There’s only so many Ph.D.s in mathematics you’re going to produce each year,” he said.

Yet another structure is a university’s hiring policy. It might not have been written to discriminate. But it can still have unintended consequences.

“When a Black faculty member, you’re trying to recruit them, and they say, ‘I need help with a down payment for a house,’ and you say, ‘We don’t do that,’ that’s an equity question,” Williams said. “If I were not a descendant of people who were denied entry into the American middle class, systematically, by discrimination in the sale and rental of housing, I might not need help with the down payment for a house in Chapel Hill. But if I’m white and affluent, then I have parents who might be able to help me with that.”

Examining every structure in an institution as large as UNC is an ambitious undertaking. But aside from the moral imperative, there’s also the marketplace. With all of higher education reckoning with racism, Carolina must compete harder than ever for educators of color. That means designing an institution where people want to come and stay.

Williams thinks this is possible, given enough resources and will. “I believe that this University, we can be a leader if we want to be,” he said. “We can be No. 1 in racial equity — if we want to be.”

Barry Yeoman is a freelance writer based in Durham.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.