The Haunting Back Home

Posted on July 23, 2020

David Zucchino ’73 (Grant Halverson ’93)

A fearless witness to conflict halfway around the world, David Zucchino ’73 remained horrified by what had happened a century before in North Carolina.

by Elizabeth Leland ’76

David Zucchino ’73 worked overseas for years, reporting on ethnic conflicts in Lebanon and apartheid South Africa, Iraq and Afghanistan, never realizing there was an epic story of violence to be told about his own state.

“How could I not have known?” he wonders now.

In a single day in 1898, avowed white supremacists purged the city of Wilmington of its multiracial Fusionist government and growing Black middle class. They burned down the Black newspaper. They killed as many as 60 Black men. They wounded dozens more. They evicted progressive city leaders — Black and white — at gunpoint and threatened to shoot them if they returned. Some 2,100 Black people fled the city and never went back.

The horrific assault was part of a statewide campaign to undo the gains that Black people achieved after the Civil War. It helped usher in Jim Crow, reshaping the state’s political and racial landscape for decades. The number of registered Black voters across North Carolina dropped from 126,000 in 1896 to 6,100 in 1902.

To justify their violence, white supremacists created a false narrative that persisted through most of the 20th century. They claimed that white heroes rescued the state from the “beast rapist and corrupt Negro rule,” a version of history repeated for generations.

Defiant armed white rioters pose in front of the burned-out shell of a building that housed the Daily Record, Wilmington’s African American newspaper. (New Hanover Public Library, N.C. Room)

Zucchino would win the Pulitzer Prize in feature writing, be named a finalist for other Pulitzers and write his first book, The Myth of the Welfare Queen, before he grasped the truth that begat Wilmington’s Lie. He found out in 1998 the way many North Carolinians did — on the centennial of the coup as Wilmington wrestled to correct the historical account and come to terms with its bloody past.

“I was shocked that I didn’t know about this and shocked that this could happen in the United States of America,” Zucchino said. “I wanted to write a book about it — as a journalist, not as an historian. But I didn’t have time to do a book then. I was traveling overseas. So I just kind of tucked it away saying, ‘Someday when I get time, I’m going to do a book on this.’ ”

That day came in 2016 after Zucchino left the Los Angeles Times, where he covered the Iraq War and reported from Afghanistan.

“I realized this story has been following me around my whole adult life.”

Among the masterminds behind the coup was businessman William Rand Kenan Sr. (class of 1864), who commanded a state militia that massacred Black residents and for whom Kenan Stadium originally was named.

And Cameron Morrison, namesake of Zucchino’s freshman dorm and a leading orator in the white supremacist movement before he became governor.

Also Josephus Daniels (class of 1885), who led the white supremacist propaganda campaign as publisher of The News and Observer,where Zucchino once worked. Carolina’s Student Stores was dedicated in Daniels’ name in 1967.

For years, Zucchino had known only positive references to those men — philanthropist, “Good Roads Governor,” progressive journalist — and nothing about the massacre and their roles in it.

“Have you heard about this?” he asked his friend Bland Simpson ’70, Kenan Distinguished Professor of English and creative writing. They were meeting as usual for BLTs at Merritt’s on South Columbia Street.

Simpson knew the basic story but would learn much more through Zucchino’s meticulous research. In the months that followed, Zucchino shared some of what he learned from letters, memoirs, newspaper articles, diaries, telegrams and other historical accounts. Finally, the day came when he handed Simpson a draft of his book to critique. Simpson took it home and began to read.

“I was stopped by the horror of it,” Simpson recalled.

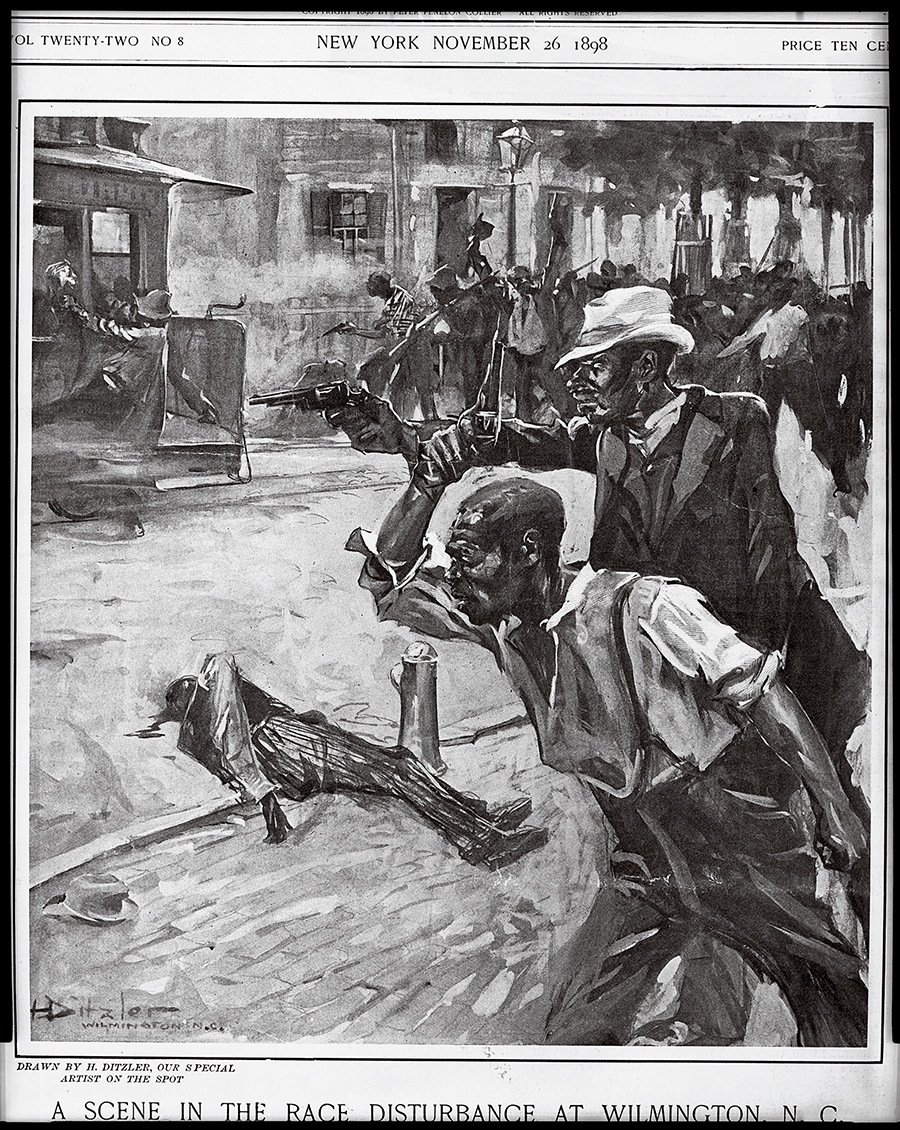

Collier’s magazine used this illustration in its Nov. 26, 1898, issue, saying it depicted “a scene in the race disturbance at Wilmington”; the Library of Congress labeled it as “[B]lack men firing handguns in the street.”

Historians had written previously about the coup — most notably African American historian Helen Edmonds, in a doctoral thesis for N.C. Central University in 1951; and two white historians, David Cecelski and Timothy Tyson, who edited Democracy Betrayed: The Wilmington Race Riot of 1898 and Its Legacy on the 100th anniversary of the coup. In 2006, North Carolina’s Office of Archives and History published a 507-page report. None of those attracted much public attention. Zucchino hoped his page-turning narrative would broaden the audience. His description of the shooting death of Black laborer Daniel Wright reads like an eyewitness account:

“He fell, his blood soaking the packed earth. Several men yanked him to his feet. Wright begged for mercy. Someone smashed him over the head with a gas pipe, drawing more blood and slamming him back to his knees. Several men yelled for him to be lynched from a nearby lamppost. They searched for a rope. But another man suggested that Wright be given a chance to run for his life. He was released. ‘Run, nigger, run!’ a man shouted.

“Bleeding profusely, Wright stumbled through the packed sand at the edge of the street. He struggled about fifty feet before gunshots sounded. He tumbled to the ground, felled by thirteen bullets, five of them through his back.”

Some African American residents of Wilmington who spoke with Zucchino had heard about the coup through family lore but knew few of the horrific details; others were unaware. “Among those who had heard of the coup, there was a reluctance among some families to discuss it within the extended family,” Zucchino said. “It was just too painful and disturbing.”

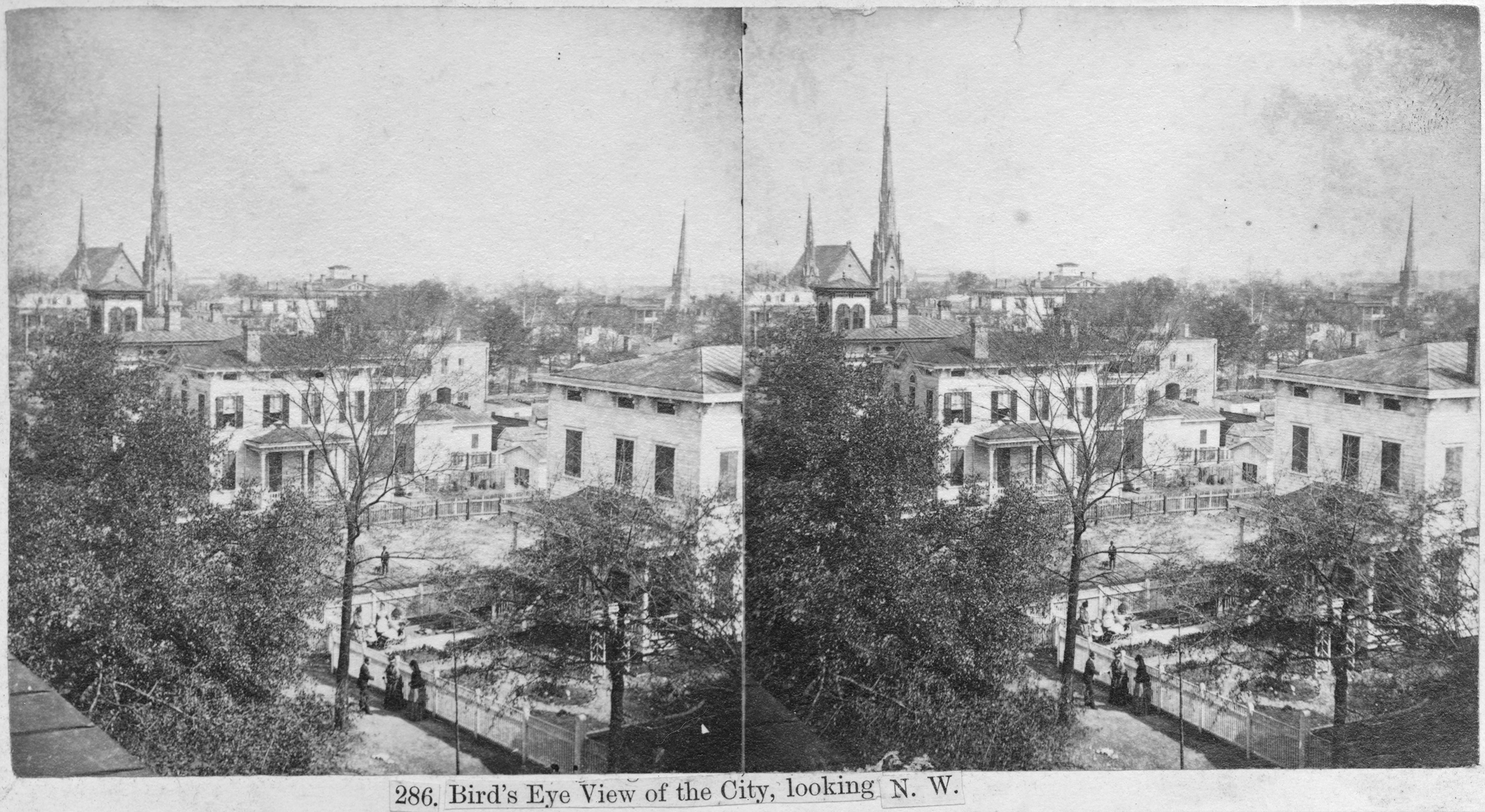

Wilmington in the late 1800s. (Library of Congress)

Zucchino, too, was horrified.

“I wrote this book to correct the historical record. I truly believe we have to confront the ugliest chapters of our history to understand the roots of racism and hate. There were lots of race riots in the United States. What makes this unique is a lot of those were basically spontaneous outbursts of white rage, usually after a Black man was falsely accused of raping a white woman.”

What happened in Wilmington was an armed coup.

“It was a planned mass killing,” he said. “It was a major event, not only in North Carolina history but in American history.”

The events of 1898 — and the subsequent cover-up — felt personal to Zucchino. Though he was born in Kansas into a military family and grew up on U.S. Army bases, including eight years in Germany, he considers North Carolina home. He attended high school in Fayetteville and earned a journalism degree from Carolina. His first job after college was with The News & Observer.

Drawn to conflict

For five years as a reporter, Zucchino commuted to Raleigh from a shabby apartment building on N.C. 86 north of Chapel Hill that he and his friends christened “Spudtowne” — the archaic English spelling for ironic effect. They gave each other nicknames that have stuck all these years. To those longtime friends, Zucchino remains Rico Cavatinni because of his Italian heritage.

Zucchino at an American military encampment somewhere in Iraq with photographer Rick Loomis.

Six-foot-two and mustachioed, with shoulder-length brown hair, Zucchino stood out among the group of young men who gallivanted about town in secondhand tuxedos and other outrageous get-ups from the PTA Thrift Shop. Their shenanigans included “Cozmic Croquet” tournaments and raucous “Spudtowne Follies” at the old Cat’s Cradle on Rosemary Street. In the much smaller Chapel Hill of the 1970s, the Spudtowne gang took on almost mythic stature.

“What was wild about Rico, he could be right in the middle of everything and get up the next day and drive to Raleigh and write an article that would win some kind of award,” said Dan Collins ’74, now a retired sports writer, who roomed with Zucchino. “He was so good at compartmentalizing things.”

Another key to Zucchino’s success as a journalist is that he comes across as down-to-earth and relatable, whether he’s speaking with a tobacco auctioneer in eastern North Carolina or a cave dweller in remote Afghanistan.

He left Raleigh for a job with The Detroit News and two years later moved to The Philadelphia Inquirer, where he stayed 21 years. In Philadelphia, Editor Gene Roberts ’54 advised his new recruit that instead of devoting time to routine, daily stories he should look instead for larger stories told through the eyes of the people affected. That advice led to Zucchino’s nine-part series “Being Black in South Africa,” which won a Pulitzer Prize in 1989.

In Zucchino’s early years as a foreign correspondent, Kacey Chapp Zucchino ’78 followed her husband abroad. In Beirut, they played a game they called “Boom” with the eldest of their three daughters, then an infant, whenever bombs exploded nearby.

“It was extremely difficult for [Kacey],” Zucchino said. “Kacey was so strong and courageous during that whole time. She sacrificed her career so I could work overseas in journalism. I really owe a lot to my wife.”

Kacey Zucchino said she long ago came to terms with her husband’s passion for storytelling even when it puts his life at risk. Or perhaps especially when it puts his life at risk.

“You love that adrenaline rush,” she said to him over bowls of homemade minestrone during lunch one day at their home in Chatham County.

Zucchino in Baghdad in April 2003 with soldiers from the 3rd Infantry Division, holding the head from a statue of Saddam Hussein that was blown off by an American tank. (Rick Loomis)

Zucchino nodded. “To be at the center of these major events and to be in the middle of it and to be the one reporting it … ” His voice trailed off. “You know the cliche is that you’re writing ‘the first draft of history.’ ”

When U.S. forces invaded Baghdad in 2003, Zucchino talked his way into embedding with the U.S. Army’s Second Brigade of the 3rd Infantry Division. As the soldiers thrust their way through the city, Zucchino rode along, documenting their surprise “thunder run” (which would become the title of his second book, Thunder Run: The Armored Strike to Capture Baghdad). He wrote that first draft of history in quintessential Zucchino style, sparing no graphic detail about a battle that left thousands dead and ended the Iraqi War:

“In the lead tank was 1st Lt. Robert Ball, a slender, soft-spoken North Carolinian. Just 25, Ball had never been in combat until two weeks earlier. … Ball had fired at soldiers in southern Iraq, but they had been murky green figures targeted with the tank’s thermal imagery system. These soldiers were in living color. Through the tank’s sights, Ball could see their eyes, their mustaches, their steaming cups of tea.

“The gunner mowed them down methodically, left to right. As each man fell, Ball could see shock cross the face of the next man before he, too, pitched violently to the ground. The last man fled around the corner of the building. But then, inexplicably, he ran back into the open. The gunner dropped him.”

For the next few weeks, Zucchino and photographer Rick Loomis slept in Saddam Hussein’s abandoned presidential palace while U.S. military tanks stood guard outside.

“We were the first ones to be in the palace,” Zucchino said. “We just moved from bedroom to bedroom because the toilets weren’t working. We went to Saddam’s personal residence and found his wedding albums, his cigars. … We wandered through this whole compound.” They heard about two engineers from the unit who went into a gardener’s cottage and saw aluminum boxes with Bank of Jordan seals on them. “They break them open. There’s $650 million.”

Wilmington parallels

The stories Zucchino brings home to the United States are legendary among his friends, who have urged him to write a memoir. “At the end of the invasion of Iraq, we wrote down 100 points of crazy — personal anecdotes about things no one would ever believe,” photographer Loomis said. “This is the story people need to read about: What it takes to go out and do this job. I keep asking him, ‘When are you going to write the real story?’ ”

Maybe one day, Zucchino said. But now that he’s finished writing Wilmington’s Lie, he feels driven to report from Afghanistan, where he has worked every other month — a schedule on pause during the pandemic — as a contributing writer for The New York Times.“It’s like my second country, Afghanistan. I’ve been going there so long, and I’ve really gotten attached to it, and I care what happens to the people there. I know a lot of people. It’s a fascinating place, a beautiful country.”

If he grows a full beard and wears a loose-fitting shalwar kameez suit and traditional pakol hat, Zucchino could be mistaken for a tribal elder when he takes trips to the provinces. “I’m not fooling anybody. But passing by in a car, an old guy with a white beard, nobody will think a lot about it.”

At the bureau in Kabul, Zucchino stands out among the other, younger, journalists. He’s the balding correspondent with close-cropped hair and reading glasses. “I’m like a grandfather there,” Zucchino said. “It’s odd. The other reporters kind of look at me like, ‘Why is this old guy here?’ ”

Why, indeed, is a 68-year-old man with a wife, three daughters, two grandchildren and a comfortable home still risking his life as a war correspondent?

After editor Alex Manly, top right, dared to stand up to the white power structure, he was threatened with lynching and told to “go to Africa where you belong.” (Joyner Library/East Carolina University)

“Because it’s so invigorating,” Zucchino said. “It’s so exciting. I love to be in the middle of stories, to actually get paid for it.” The scary moments, he said, are part of the thrill. “I go to these villages in remote areas where they’ve never met an American.”

During the time he spent working on Wilmington’s Lie, often holed up in Wilson Library, the change of pace felt good — until it didn’t. By mid-February, as his book tour wound down, Zucchino was impatient to return to Afghanistan. But even as he anticipated his next assignment, he reflected on the lessons he hoped his book would impart.

He talked about Alex Manly, editor of Wilmington’s African American newspaper in 1898. When Manly dared stand up to the white power structure, he was threatened with lynching and told to “go to Africa where you belong.” Manly fled Wilmington before the coup and never returned.

The cover of the book features a photograph of the burned-out shell of a building that once housed the Daily Record newspaper. Defiant armed white rioters pose out front.

“I think we can learn a lot from the scapegoating and dehumanizing and marginalizing of people, in this case, Black people,” Zucchino said. “I see echoes of that today. … The message is not nearly as blatantly racist, but it’s out there: If you’re Muslim, if you’re LGBTQ, if you’re part of Black Lives Matter, if you are an Hispanic immigrant crossing the Southern border, you’re portrayed as a threat to the traditional American way of life.”

For Zucchino, Wilmington’s Lie is as much a cautionary tale as it is a historical account.

Elizabeth Leland ’76 is a freelance writer based in Charlotte.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.