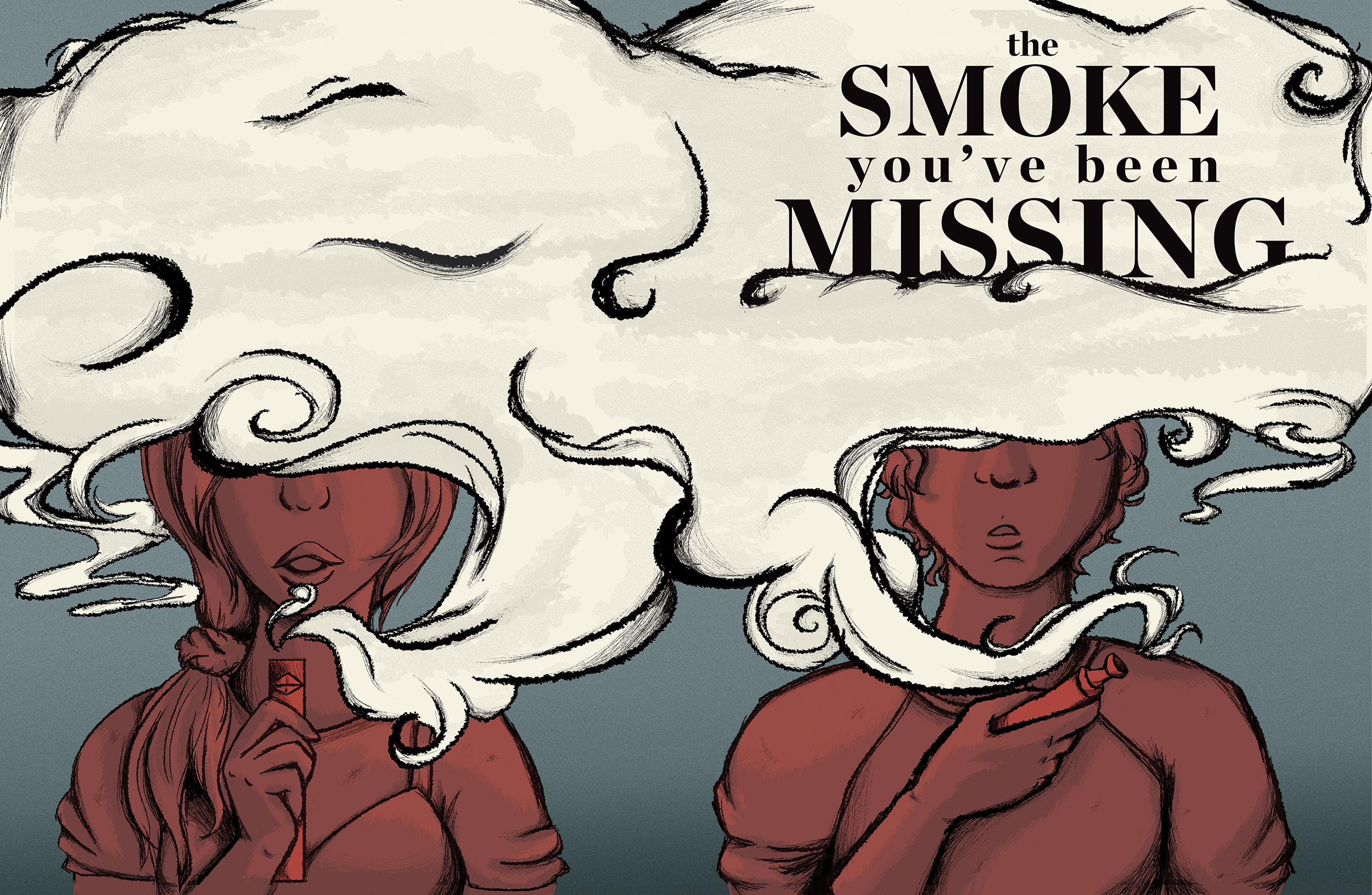

The Smoke You’ve Been Missing

Posted on March 12, 2020 A UNC toxicologist listened to kids talk about vaping. She wants to know why health regulators dropped the ball on e-cigarettes.

A UNC toxicologist listened to kids talk about vaping. She wants to know why health regulators dropped the ball on e-cigarettes.

By Beth McNichol ’95

Illustrations by Haley Hodges ’19

On a Tuesday night in mid-November, the principal of Riverside High School in Durham opened a PTA meeting with a moment of raw honesty. The previous winter, Tonya Williams Leathers said, two reporters from the school newspaper had asked to interview her for an article on vaping. She had been incredulous.

“I said, ‘What? What are you talking about? Nobody vapes,’ ” Leathers recalled telling them. Then, she said, it was the students’ turn to be incredulous.

“They gave me an entire education about how … it had become widespread,” she said. “And then I just became hypersensitive to it. I smell it in the hallways, I smell it outside. It smells very fruity; it doesn’t smell like cigarettes. And you can’t always see the smoke.”

You can’t always see the smoke.

The featured speaker that night, toxicologist Ilona Jaspers, could not have put it better. On the table in front of her was an array of vaping devices that she carries with her in a Ziploc bag, a kind of e-cigarette education kit for the uninitiated — which was everyone in attendance, save for a small panel of nonvaping Riverside students who came to share their perspective on the culture. As Jaspers will tell you, every high school student knows the names of these devices and what they look like, whether they vape or not.

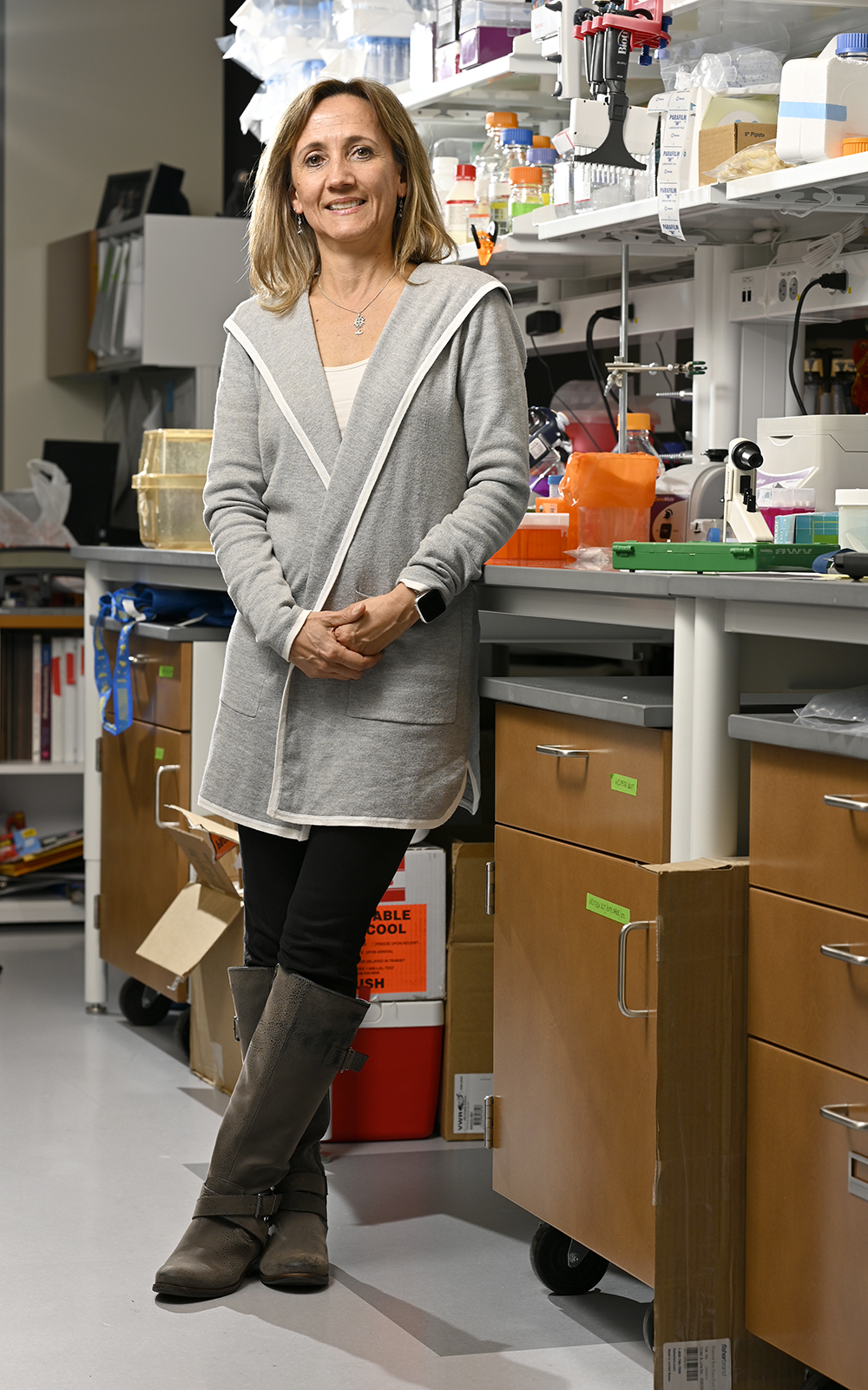

Ilona Jaspers has become the town crier for vaping’s known and unknown health dangers to the developing adolescent brain. (Grant Halverson ’93)

By contrast, most parents and health care professionals Jaspers meets have neither seen in person nor held a Juul, which resembles a USB drive. And if they haven’t seen the Juul, which commanded 75 percent of the vaping market in 2018, they certainly don’t know the other devices. Among them: the Suorin Drop, which has the metallic heft and feel of a fidget spinner and boasts e-liquid pods that contain the nicotine equivalent of 90 cigarettes; and the PuffIt2, which is disguised as an ordinary asthma inhaler. This is just a sampling, Jaspers warned. Out there in the unregulated Wild West of vaping, she said, there are products that look like fitness tracker bracelets and others built directly into the hoods of sweatshirts.

“Please take these devices in your hand and hold them so you’ll know exactly what they are,” Jaspers implored us — and we did, but with uncertainty about which part to look at and what to look for, as if we were travelers in a foreign land.

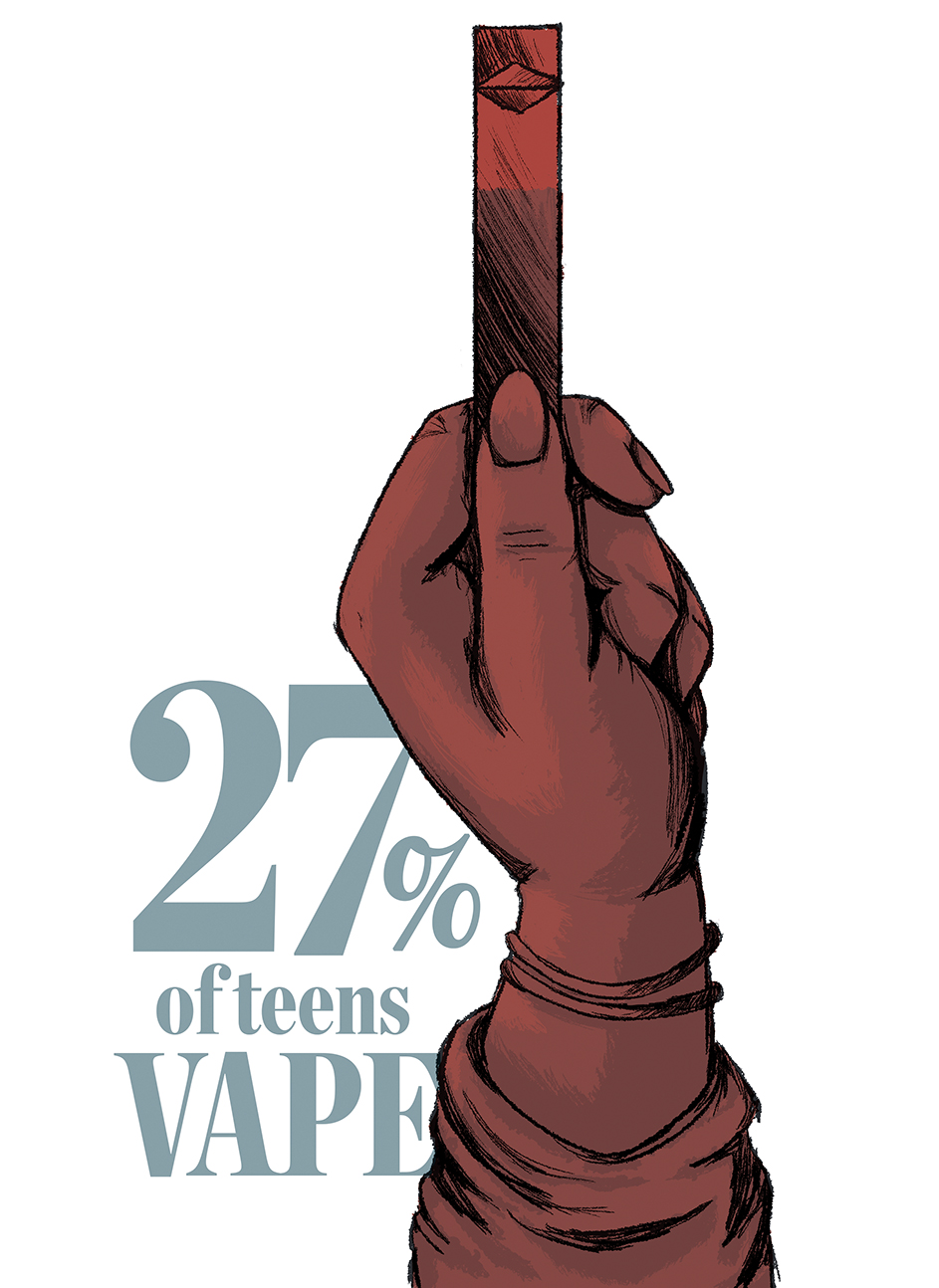

How has it come to pass that 27 percent of American teenagers are now using e-cigarettes when the generation before them has moved so far beyond tobacco products that just holding one feels like an illicit act? Spend a month or two following Jaspers, a professor of pediatrics at UNC, and you’ll begin to see all the smoke you’ve been missing around e-cigarettes — starting with the word “vape” itself.

E-cigarettes, she said, emit neither smoke nor vapor. They emit aerosol.

“And what do you associate with that word?” Jaspers asked the group. “A spray can. Chemicals. Something nasty. But it was beautifully marketed as vapor. I’ve heard people say, ‘What’s the big deal? It’s just water vapor with flavor.’

“No. It’s a chemical aerosol. If we would’ve been on top of things from the beginning to change the language, to actually say what it is, I wonder if that terminology would have made a difference.”

Jaspers has studied the effects of air pollution and cigarettes on lung health since she came to UNC for a fellowship in 1997. She lands large grants and publishes her work in peer-reviewed journals that, she jokes, “about 20 people read.” She is part of a jargon-laden world of scientists who often have the social inclinations of a petri dish.

“There’s a reason why there’s, like, five PhDs in Congress and none of them are biomedical,” Jaspers said. “They don’t like to leave their labs and go out into the big, bad world and talk to people.”

E-cigarettes emit neither smoke nor vapor. They emit aerosol. “And what do you associate with that word? A spray can. Chemicals. Something nasty. But it was beautifully marketed as vapor. ”

—Ilona Jaspers

But for the past four years at high schools like Riverside, in meeting rooms with pediatricians, at science museums and coffee shops and wherever the public will listen, Jaspers has become the town crier for vaping’s known and unknown health risks — and of nicotine’s undeniable dangers to the developing adolescent brain. While federal regulators have talked about action to protect minors, Jaspers has been unwilling to sit quietly.

“When I realized how bad e-cigarette use was in the high schools, I thought, ‘If I don’t do this, who will?’ ” said Jaspers, who also directs the toxicology curriculum at UNC and is the mother of a junior and a senior at Chapel Hill High School. “If I don’t go out and talk to people and educate them about it and find a way to communicate with them, who will?”

Plenty of stories have been written in the past year about Juul’s fruity flavorings and splashy marketing campaign aimed at youth — replete with models in ponytails wearing backpacks.

Jaspers talks about that, too. But she’s long explained the “brilliant evil” that is Juul’s chemistry to her audiences as well, how the company developed a formulation of nicotine that was not only more potent but easier to tolerate than cigarettes. While a drag on a cigarette would hit the back of the throat with a burning sensation, Juul’s hit was smoother, she said, meaning users could puff nonstop without discomfort. All those factors added up to a teenage vaping epidemic.

The students and parents at the PTA meeting also blamed Juul, standing up for a generation that got hoodwinked. Jaspers met them in the moment. You want to see the smoke? Here it is, she said.

“This is not your fault,” she told them. “You were steamrolled by a company that, from the get-go, really started marketing it to you. It was very clear that the demographic they were targeting was not me, and it was not the smoker who was trying to quit smoking. Absolutely not. It was you.”

Running at the problem

The number of punches Jaspers has pulled since 2013, when a classmate of her fifth-grade daughter brought an e-cigarette to school thinking it was a toy, stands at exactly zero. She is a bolt of straight talk, the kind of no-excuses leader that teenagers themselves might call “kick-ass,” and an athlete who, at age 50, runs just over an 8-minute-mile marathon pace despite a torn meniscus. (That’s at least a minute-and-a-half faster than the average marathon pace, regardless of age or gender.)

“Patience,” she deadpanned, “is not one of my virtues.”

Jaspers grew up in Cologne, Germany, where she smoked her first cigarette at 14 and her last at 17, quick to start and fast to finish, in true Jaspers fashion. Just a “peer, stupid thing to do,” she said, a habit she gave up after earning a tennis scholarship to Seton Hall and recognizing the folly of taking a nicotine habit with her to twice-a-day practices.

Last October in her hometown, she completed her 14th marathon in 10 years, racing across the Rhine River and through the downtown streets, passing a couple of vape shops along the way. She probably was thinking about e-cigarettes anyway.

“Running, for me, is very therapeutic,” said Jaspers, who holds joint appointments at UNC in environmental science and engineering and in microbiology and immunology. “It’s the only time I don’t have phone, email, texts, kids, husband, students, anyone. It’s just me, and I can actually think. I have a problem that bugs me, and I try to come up with a solution. Like, ‘How can I get this across? How can I tell people flavors are bad? What’s a good analogy?’ You’re stuck on something, and somehow it gets unstuck. I come home from a run, and it’s like, ‘Oh. This is how it works.’ ”

Her lab students know exactly how it works.

For Jaspers, the question always has been: Are e-cigarettes safe, period?

“Oh, we’d always pay the price for her runs,” Philip Clapp, a past doctoral student of Jaspers, said with a laugh. “She would come back and say, ‘I had a marathon this week and I got to run for several hours, and I think we need to do this study. There’s this call for papers here, and I think you should do this …’ And I’m just like, ‘Oh, my God. She can’t go to any more races.’ ”

In 2013, the same year Jaspers’ daughter saw the e-cigarette at school, UNC won a federal grant to study new and emerging tobacco products. Jaspers’ lab began investigating vaping in earnest.

At the time, many researchers were comparing e-cigarettes’ health safety to those of traditional cigarettes, because the former had been heralded early on as a better alternative. One such study, by Public Health England in 2015, still is routinely cited by vapers who oppose regulation and by new companies looking to enter the $14 billion industry. In it, researchers found e-cigarettes to be 95 percent safer because they lacked the carcinogens known to be produced by combustible cigarettes.

“But e-cigarettes are not burning tobacco, which is where these cancer-causing agents are coming from in cigarettes,” Jaspers said. “I could have made that statement without actually doing any science, because it was the wrong premise for that kind of comparison.”

For Jaspers, the question always has been: Are e-cigarettes safe, period?

To help answer that, Clapp zeroed in on the e-cigarette flavorings that were instrumental in attracting teenagers; the agents, which mimicked sweet treats such as cotton candy or pumpkin spice latte, often were so potent that they masked the presence of nicotine for users. In Jaspers’ lab, they discovered “bucketfuls” of the flavoring chemicals in e-liquids.

An opened Juul pod reveals the heart of the apparatus that uses nicotine salts, which allow for more nicotine consumption with less throat irritation, available in flavors attractive to teens. (Grant Halverson ’93)

“Because these people weren’t trained in any sort of toxicology,” Clapp said, “if one drop of a flavoring was good, then 10 drops had to be better. And if that was better, then 100 drops might be even better than that, so they just kept adding it. We were just shocked to see the concentration in a lot of these products, and that was what was going directly into people’s lungs.”

One of those chemicals, the highly reactive cinnamaldehyde, yielded a surprising result in their studies. When they placed an e-liquid with the cinnamon flavoring on lung cells, the cilia on the surface — the tiny hairs that move in unison to clear foreign substances like pollen — immediately stopped beating. Two hours later, the cilia began to work again. The e-liquid had given them temporary paralysis.

“Basically, a really key defense just stopped working,” Clapp said. “You can imagine that if your ability to clear stuff out of your lungs all of the sudden stops, then things like bacteria and viruses or pollen or whatever will just reside in your lungs for a longer period of time, increasing your risk for infections.”

That could be especially problematic for people with existing airway issues, such as asthmatics — who, Jaspers noted, have been shown in multiple studies to be more likely vapers than nonasthmatics. In 2019, Meghan Rebuli, a postdoctoral student in Jaspers’ lab, helped author a case study of two teenagers who were admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit at UNC Hospitals with severe respiratory distress related to asthma. They were so critically ill they required ventilators and ECMO, in which a patient’s blood must be removed and oxygenated by a machine outside the body before being returned. Researchers learned that both the teens, who were 14 and 16, had been vaping before their illness. One continued vaping and wound up in the hospital six more times.

Rebuli also has worked on research with Jaspers that shows vaping not only has the same dampening down effect on the airway’s immune system as cigarette smoking but that the effect also is more pronounced in e-cigarette users’ lungs.

These results preceded the outbreak of vaping-related illnesses that emerged last summer in the United States, with more than 2,000 cases and 47 deaths reported so far. At UNC Hospitals, Jaspers had told pediatric residents how to look for vaping-related illnesses, which the CDC has dubbed EVALI (e-cigarette or vaping-associated lung injury). Teenagers and young adults often came to the hospital with symptoms as varied as severe gastrointestinal upset and seizures in addition to pneumonia-like features — a “toxic overload” taking over their systems, Jaspers said.

At least two adolescents with EVALI were in the UNC PICU each week, frequently on ventilators, some as young as 13. At one lunchtime meeting with Jaspers in October, more than half of a group of about 40 pediatric residents said they had encountered cases of EVALI since she’d first spoken to them about it four weeks earlier.

At least two adolescents with EVALI were in the UNC PICU each week, frequently on ventilators, some as young as 13. At one lunchtime meeting with Jaspers in October, more than half of a group of about 40 pediatric residents said they had encountered cases of EVALI since she’d first spoken to them about it four weeks earlier.

“That was alarming,” Jaspers said afterward. “That was shocking to me. They’ve been probably seeing it for a while without systematically documenting it.”

Similar cases have been reported nationwide, she said, as far back as 2016. But something clearly had shifted to cause so many to fall ill over just a few months.

The CDC’s analysis of EVALI lung fluid found that vitamin E acetate, an additive used in some vapes that turns sticky in the cool space of airways, was present in each of 29 patient samples. But correlation doesn’t prove cause; only a controlled laboratory study of the devices and chemicals used could help provide those answers, Jaspers said. And because 82 percent of the users vaped a product with THC, the psychoactive ingredient in marijuana, she and other researchers who receive federal grant money are forbidden to study most of the products to blame for the spate of EVALI cases — even in states where the substance is legal to purchase.

“Is it the THC alone that causes it?” she asked. “Is it the flavors alone? Is it the nicotine? Is it the vitamin E acetate? Or something else in there? Nobody knows, because we can’t study it. We are basically flying blind.”

At Riverside in November, a student noted that many of his peers were skeptical about the sudden EVALI risk because it seemed to appear out of the blue.

“It could be that this is all caused by one factor, one ingredient, one brand that we don’t understand yet,” Jaspers told the student panel. “But I wouldn’t take that risk. We are basically conducting a giant human experiment. Does that scare you enough?”

To have a mom like this

If there’s one thing Jaspers knows from being the parent of teenagers, it’s that high school students don’t like to be played.

“Kids have their phone all the time, so you can’t B.S. them,” she said. “They’ll fact-check you in an instant. You can’t tell them lies. You can’t do hyperbole. But at the same time, you have to develop a way to get through to them.”

When Elise Hickman joined Jaspers as a doctoral student in 2018, she harbored an interest in teaching — something she wouldn’t be doing as part of a basic science lab. But Jaspers had an idea. She sent Hickman to meet with Dana Haine, a K-12 science education specialist at the UNC Institute for the Environment who had been assisting with Jaspers’ outreach. Over the course of a year, Haine and Hickman developed an advanced placement biology curriculum on e-cigarettes using the cinnamaldehyde research published by Jaspers’ lab.

The course, which Hickman and Haine piloted in several schools, was made available online last fall. It provides opportunities for data analysis and interpretation so students can draw their own conclusions about vaping. “The idea was to get them thinking about e-cigarettes and health without just telling them, ‘Don’t do this,’ ” Hickman said.

Jaspers also has leveraged the knowledge of her resident experts on teenage culture — her children, Ella and Kalvin Matischak, and any of their friends who happen to wander into her kitchen for a snack. She calls them her “kitchen table focus group.” (Some meetings take place in soccer carpool: “They’re trapped in your car and can’t go anywhere, so they have to talk to you,” she said with a smile.)

Her outreach events are peppered with information she’s gleaned from teenagers — the consensus that many more than 27 percent of high schoolers vape, the knowledge that the habit isn’t contained to a certain social clique; entire sports teams vape, while band members have been known to hide their devices in their instruments.

“It could be that this is all caused by one factor, one ingredient, one brand that we don’t understand yet. But I wouldn’t take that risk. We are basically conducting a giant human experiment. Does that scare you enough?”

—Ilona Jaspers

For her part, Ella was surprised by how much even her mother didn’t know at first about e-cigarettes in schools.

“I just assumed that everyone knew what a Juul looked like,” said the nonvaping Chapel Hill High junior. “But I can see how, if you weren’t in the environment that I am every day at school, that it would be surprising, that you just wouldn’t expect it.”

Ella and her friends have helped Jaspers speak the language and recognize popular devices, so that Jaspers could create guidance for health care professionals who might not be asking the right questions or using the right terminology. Jaspers once showed her kids’ friends a poster that referenced using THC. “What’s that?” they asked. In the teenage world, they only knew it as “dabbing.”

“You have to have an ear on the ground here,” Jaspers said, “because that’s how you find out what’s really happening.”

Miscommunication is one of the biggest problems with both youth vaping and EVALI. Until 2018, the CDC’s National Youth Tobacco Survey didn’t include e-cigarette brand names in its questions; the number of underage users was underreported because kids didn’t associate the Juul with the term e-cigarette. Some students, thanks to poor labeling and candy flavorings, didn’t even realize it contained nicotine. They didn’t “vape,” they “Juuled,” said Jaspers. The same challenges remain for health practitioners when asking teens for health history, she said.

“You’re failing these kids”

Over the past year, Jaspers has been running one long marathon of research and outreach, becoming increasingly frustrated with a Food and Drug Administration that she said has dropped the ball on e-cigarette regulation through both the Obama and Trump administrations. In January, the White House announced it would ban all flavors — with the exceptions of menthol and nicotine — in Juuls and other refillable cartridges. The move is unlikely to have much effect on teenagers, however; the FDA flavor ban does not apply to disposable products like the STIG e-cigarette, which was threatening Juul’s popularity among high schoolers even before the new rule, Jaspers said.

“We know these flavors are not safe when they’re inhaled,” Jaspers said. “So, you’re failing these kids. You’re failing them. Stop. Sometimes you just want to scream, ‘Why are you not doing something?’ ”

“We know these flavors are not safe when they’re inhaled,” Jaspers said. “So, you’re failing these kids. You’re failing them. Stop. Sometimes you just want to scream, ‘Why are you not doing something?’ ”

Jaspers wants a lot more done to protect youth in the U.S. She wants a higher tax on tobacco and e-cigarette products to help fund cessation programs for nicotine-addicted teens — for whom replacement therapies and drugs have been proven both ineffective and unsafe. And if e-cigarettes are important as a cessation tool for adult smokers, as both the FDA and the vaping lobby contend, the powers-that-be should reflect that in their actions, Jaspers said.

“Is it a smoking cessation tool?” she said. “I don’t know. I’ve not seen conclusive evidence that it is. Maybe it is. I’m not going to say no to that. But if that’s the case, don’t make it completely unregulated. Have it given out as a prescription or regulated over the counter. Make it affordable. If people really want to quit and the science supports that, then treat it as such. Market it as such. Sell it as such.

“I’ve been called an alarmist by the vaping industry,” she said. “But I am going to wear that as a badge of honor.”

They’ll have a hard time slowing down Jaspers, who plans to keep talking, needling, questioning and racing for answers — in and out of the lab. One teenager will be hanging on her every word.

“That’s why she’s so successful — because she doesn’t take crap from anybody,” said Ella, who said Jaspers is the person in her life she looks up to the most. “And that’s a good thing to have.”

Beth McNichol ’95, a freelance writer based in Raleigh, is a former associate editor for the Review.