Threading the Needle

Posted on March 12, 2021

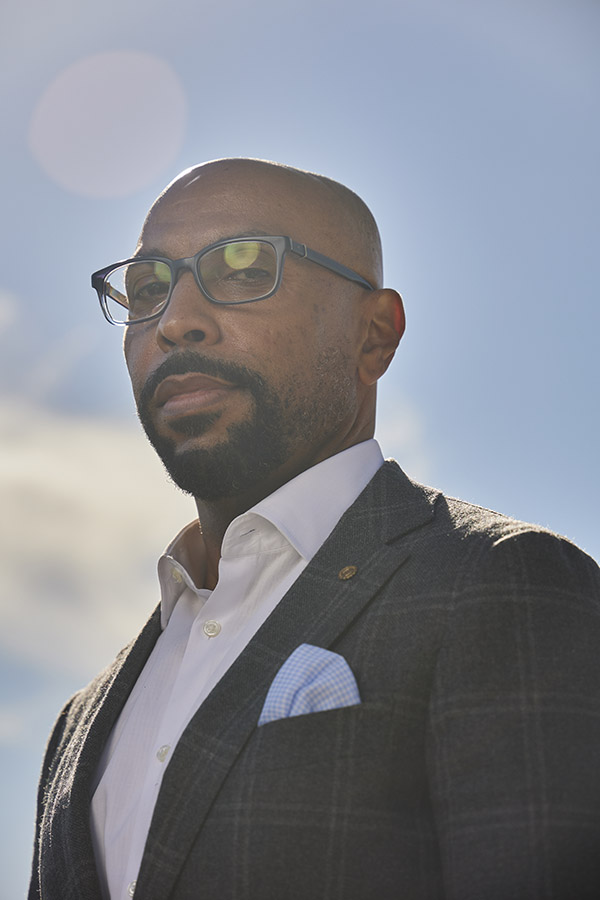

Nashville Super Speedway track president Erik Moses stands in turn four of the track. (Jon Morgan/AP Images for Carolina Alumni Review)

When Erik Moses ’93 welcomes fans to the racetrack NASCAR hired him to run, he’ll be backed by years of experience running high-profile sports ventures. This one has a difficult history.

by George Spencer

When your last name is Moses, people have mountaintop expectations. In law school, a professor called on Erik Moses ’93 in class and demanded: “Moses, you’re the lawgiver! What do you think about this case?”

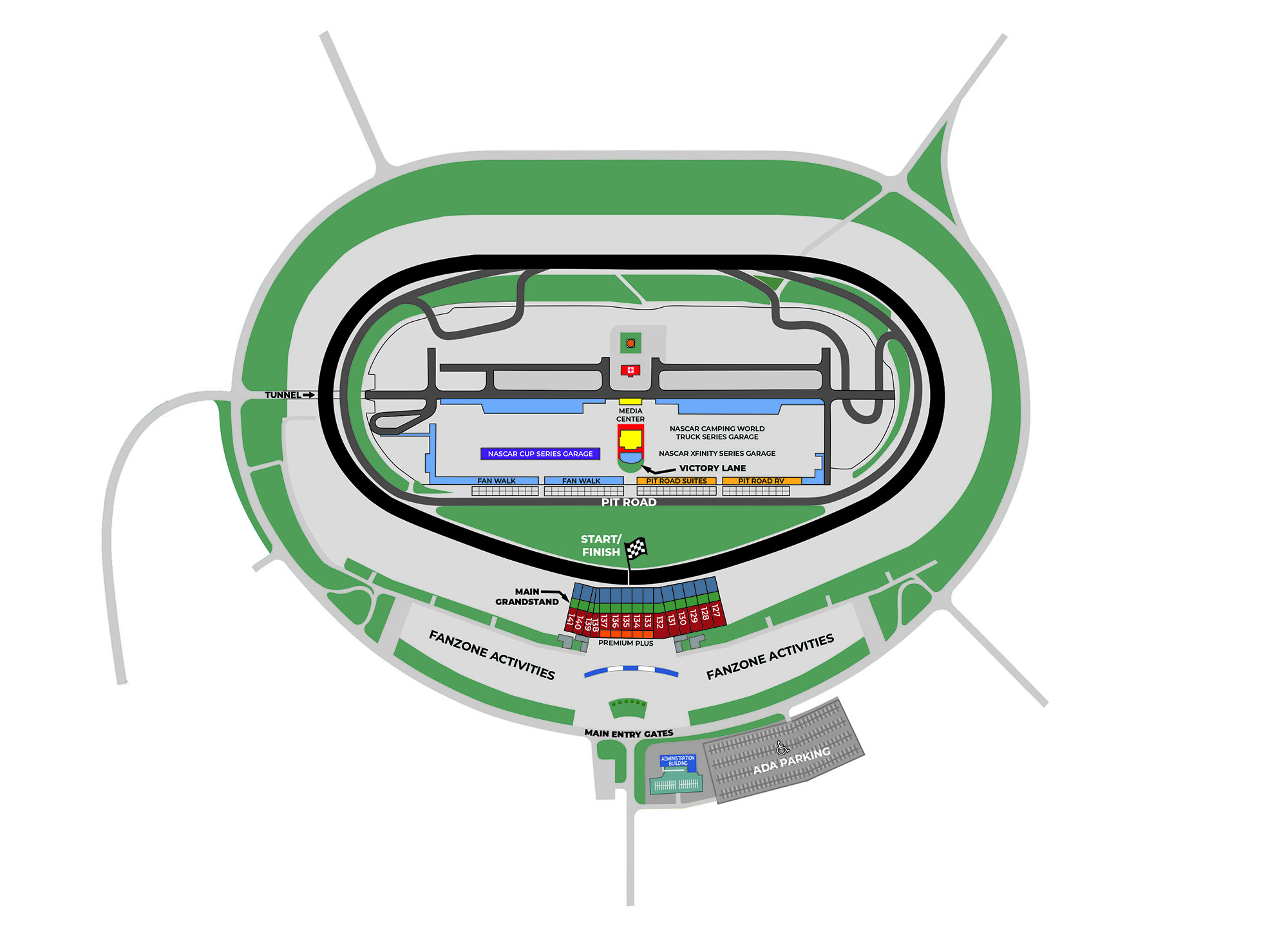

Today Moses, a veteran sports and entertainment marketing executive, is leading NASCAR to the promised land of Tennessee. He is the new president of Nashville Superspeedway, a long-dormant 1.33-mile oval track 35 miles from downtown.

The National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing gave up on Music City a decade ago. Make that 37 years ago for the premier show, the Cup Series. Even though the sport’s moonshine-infused Southern origins had good ol’ boys in souped-up jalopies outrunning revenuers, Tennesseans never flocked to less prestigious races in Nashville.

The 1 1/3-mile concrete oval, built in 2001 with a permanent seating capacity of 25,000, can be converted to a short track, a drag strip and a road course.

Now with only a few months to prepare, $10 million in renovations underway and much promotion needed to attract younger generations of fans, the Monster Energy NASCAR Cup Series is scheduled to return to Nashville on June 20. Moses must steer a tricky course.

There’s one more thing. Moses, 50, is the first African American to oversee operations at a track where NASCAR races, and the issue of racism is a daily reality for a sport that has fought image problems since its founding in 1948.

Author Tom Wolfe, in a 1965 Esquire profile of champion driver Junior Johnson, captured how many saw NASCAR: “It was immediately regarded as some kind of manifestation of the animal irresponsibility of the lower orders. It had a truly terrible reputation. It was — well, it looked rowdy or something … it wasn’t just the plain excitement of it. It was something deeper, the symbolism. It brought into a modern focus the whole business, one and a half centuries old, of the country people’s rebellion against the Federals, against the seaboard establishment, their independence, their defiance of the outside world.”

Today, though 75 percent of its races and 60 percent of its fans are outside the South, NASCAR struggles with the perception that racism permeates the sport. Last June, it banned Confederate flag displays. Days later, at the worst possible time as race riots hit U.S. cities, a noose-shaped garage door pull-handle was found in the garage of Bubba Wallace, the top circuit’s only Black driver. But garages had been randomly assigned. An FBI investigation concluded its presence was a coincidence, but PR damage had been done.

“Many of my conversations over the last couple of months have been around this topic, because it really is in many ways like threading a needle,” Moses said. “You have to figure out how to be welcoming to all — or most — without turning off others, and that’s a challenge.”

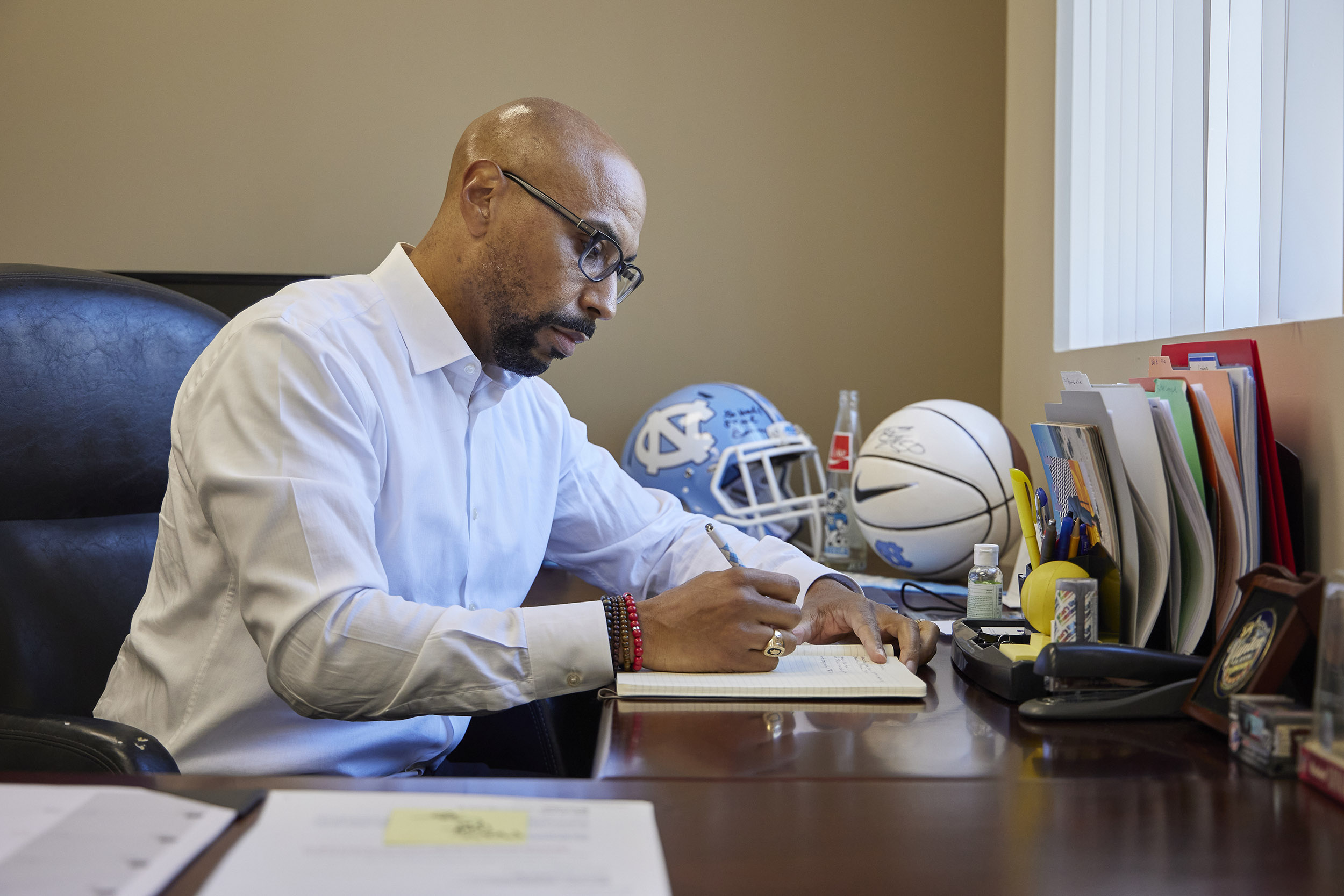

Over a 24-year career in Washington, D.C., Moses hit home runs for the nation’s capital. He helped swing financing for the stadium deal that brought Major League Baseball back after 34 years. During a decade as senior vice president at Events DC, he acted as a kind of sports commissioner for the District. The St. Elizabeth’s East Entertainment Arena, where the WNBA Mystics play, was built on his watch in one of D.C.’s poorest neighborhoods. He secured World Cup playoffs, two college football bowl games and corporate sponsorship deals while managing RFK Stadium and masterminding pop-up concerts for Stevie Wonder and rapper Wale.

Erik Moses ’93 (Jon Morgan/AP Images for Carolina Alumni Review)

He produced an inaugural reception for President Barack Obama at the D.C. Armory, which he managed, and backstage got the surprise of his life when he discovered Beyoncé standing beside him. (“She has a really beautiful spirit. You can really feel it coming off her,” Moses recalled.)

To meet his new challenge, Moses muses about a nonbiblical namesake — Robert Moses, known as the mastermind behind much of the public works that reshaped New York City in the 20th century.

“I like to think of myself as a builder. Maybe I’m a distant relative,” he said. “I have a builder mentality that comes from wanting to be in situations where I can use my IQ and EQ [emotional intelligence] to get things done. I believe in the power of partnerships. Partnerships are all about building trust.”

When asked what he misses most in today’s pandemic-restricted world, Moses says it’s the ability to form friendships. “In meeting strangers, you have opportunity to find common ground with somebody you never would have expected to. That always fortifies my faith in humanity. You find things in common, share a laugh. You walk away feeling there’s a chance we may be able to make this thing work down here.”

“It is on you”

Blessed with a sunny nature, Moses has an easygoing manner and dapper style that go far toward building bridges. He rarely dresses without a pocket square and floral boutonniere in his suit. He favors designer Tom Ford’s quip: “Dressing well is a form of good manners.” Trim, thanks to weekend cycling treks, he looks far younger than his age. Until recently he sported a goatee and moustache. “I’m trying to shave the years off,” he said.

He has a history of powering through to the finish line and admits that as a novice attorney at the elite D.C. law firm Dow Lohnes he learned the hard way to keep the pressure on. A newly minted Duke law grad, he handled closings for clients buying and selling radio and TV stations. On one occasion, Moses relied on another lawyer who promised to get him paperwork. She let him down. When the closing was delayed, Moses’ boss took him to task.

During that foreboding moment, he said, “the lesson I learned was: ‘It is on you.’ You have to get it all done. You are responsible from A to Z. You can’t ever take your foot off the gas.”

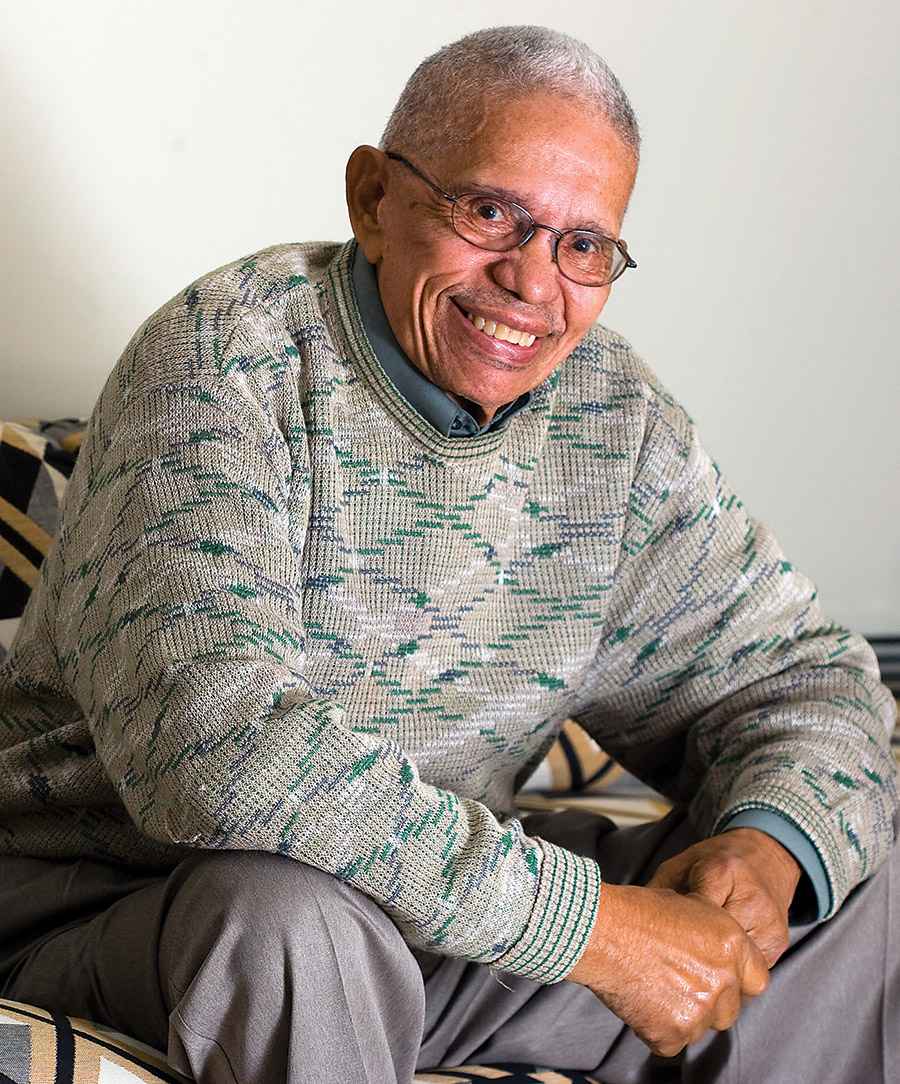

Moses’ spiritual mentor is his great-uncle J. Kenneth Lee. One of the first five Black students to attend the UNC School of Law in 1951, Lee kept the pedal flat to the metal for decades. The 13th of 14 children, Lee grew up in poverty. After getting his UNC degree in 1952, he went on to serve as legal counsel in 1,700 civil rights lawsuits and became an entrepreneur who opened a theater and a trade school, developed shopping centers and a nursing home, and in 1959 started the state’s first Black-owned federally chartered savings and loan association.

Moses’ great-uncle was J. Kenneth Lee ’52 (LLBJD), one of the first Black students to enter UNC’s law school. “He was a pioneer, a barrier breaker,” Moses says. “When somebody like that is in your family, it makes you look at yourself differently.”(Greensboro News & Record/ H. Scott Hoffmann)

“He was a pioneer, a barrier breaker,” said Moses, who grew up in Somerset, N.J., and moved to Greensboro before his senior year in high school to help secure in-state admission to Chapel Hill. He lived with his grandmother, and Lee’s home almost adjoined her backyard.

“When somebody like that is in your family, it makes you look at yourself differently,” Moses said. It forced him to reexamine obstacles he faced compared to Lee’s.

“You go, ‘You’re OK. You’re upset because you can’t catch a taxicab.’ Right. That may be something that’s not good, but imagine going to a football game as my great-uncle did and having a whole section to yourself, because none of the white students will sit near you, or being my mother who was one of the early Black students at UNC-Greensboro, and when one of her Black classmates dropped out, a professor says in the classroom, ‘There’s another n—– on the woodpile.’ In class. Can you imagine? You’re there to learn, and the person who’s supposed to be imparting knowledge is saying something like that. It was a different time. I have drawn inspiration from their struggle, and I hope I have done some things to make them proud.”

Moses says Lee’s biggest impact on him was his entrepreneurialism. As a child, he heard yarns about the young Lee buying candy to sell at marked-up prices to siblings. “While he was a lawyer, he was also a businessman. I took from that that your vocation may be lawyering, but it doesn’t mean that’s all you can do.”

Moses felt he had to make a statement by going to Carolina, because Lee, another great-uncle and his father all attended the law school. A political science major, Moses remembers helping fight for a freestanding Black cultural center on campus by marching “one dark night” with students to then-Chancellor Paul Hardin’s home to voice their demands for what was to become the Stone Center for Black Culture and History.

Today, Moses and his wife, Mioshi, an AARP executive, have two sons, ages 20 and 14. “I get to tell my kids about that,” Moses said with a chuckle. “When my oldest says, ‘You guys were the Do-Nothing Generation,’ I’m, like, ‘Hey, hold on a second! We did quite a bit. We dumped apartheid. We fought for things on campus. Don’t think y’all are the first since the 1960s to protest actively.’ ”

When Moses reflects on the summer of 2020’s violence and America’s promise, he thinks about “how we are able to reconcile the good and the promise of America, which I think is like no other country on the face of the planet, with some of its history. It’s hard. It’s the quintessential American problem — how do we reconcile those things and how do we rally around our better angels? That’s the struggle of many of our lifetimes.”

He lives this out in his own household.

“I have a son who came of age with the killings of Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice and Sandra Bland who feels like he’s being hunted and under attack at all times. He doesn’t want to be patient and doesn’t want me to tell him or his generation how they should protest injustice after 400 years, and I get it. I understand, but I also have been fortunate enough to live long enough to see progress, to see a Black man with a name like Barack Hussein Obama elected twice by convincing margins. If you had put a gun to my head at any point in my lifetime and asked me if that would happen in my lifetime, I would have said, ‘No way in hell.’ ”

“Taking it all in like a kid”

Moses had an epiphany about NASCAR at the first race he attended. It happened at 1 p.m. on Oct. 6, 2019, at Dover International Speedway in Delaware. (Dover Motorsports, a publicly traded company, owns the track there and in Nashville. Moses works for it, not NASCAR itself.)

In 90 minutes, the 100-decibel tsunami of the Drydene 400 would engulf 80,000 spectators who had flocked there on a perfect fall day for their fix of speed, sound and the aroma of gasoline and burning rubber. Soon a herd of 38 mad, magnetized jellybeans would roar around the one-mile banked oval track at speeds of up to 160 mph for three hours.

Nearly 30 years earlier, a college friend had talked Moses into going for a spin at the Richard Petty Driving Experience at Disney World, in which amateurs get to drive stock cars fast under controlled conditions. “He grew up riding dirt bikes and fast cars like so many young men and women in the South do. He’s African American. He loved fishing, hunting and driving fast stuff. We go down there, and I get in the car with him. He comes out of the pits doing, like, 130 up on a banked track.

“In meeting strangers, you have opportunity to find common ground with somebody you never would have expected to. That always fortifies my faith in humanity. You find things in common, share a laugh. You walk away feeling there’s a chance we may be able to make this thing work down here.”

— Erik Moses ’93

“My brain can’t wrap around why the car is not flipping over,” Moses recalled. “I get out of the car happy to be alive and realize, ‘Oh, yeah, for me the debate in my head whether NASCAR drivers are athletes is over.’ ” But that thrill failed to make Moses a believer. For the next three decades, he rooted for the Lakers, Nationals and Cowboys. He never watched NASCAR on TV.

On this day in Dover, Moses saw no burning bush. What happened was more subtle, a moment of quiet thunder.

He had selfish motives for being there. He was president of the DC Defenders, a football team in the new XFL league. Its first season began and, thanks to the pandemic, ended six months later after five games in March 2020 with a curt Zoom call from headquarters. Moses and his staff learned the XFL was dead. They were fired. “The league’s president read a statement. The line went dead. That was it,” Moses said. “To say I was surprised would be an understatement.”

But back on that October Sunday, when Moses had been spending sleepless nights worrying about his team and ticket sales, he came to Dover with the notion he might find event marketing and venue management ideas. Along with thousands of fans, he strolled the eight-acre Fan Zone next to the Speedway to enjoy its carnival atmosphere. Moses had a well-trained eye for evaluating crowds and venues, yet on this day, he recalls “taking it all in like a kid.” He had his picture taken beside a food truck bearing the image of driver Dale Earnhardt, whose death in the 2001 Daytona 500 caused mourning among millions of fans.

Something unexpected caught his eye — “I saw more brown faces in the Fan Zone than I expected.” Indeed, 25 percent of the sport’s fans are Black or Hispanic (up from 20 percent in 2011), according to NASCAR, yet besides Wallace, the only other driver of color is Mexican-born Daniel Suarez.

Moses joined the fans ambling along pit road at Dover. He wanted to get a close look at the cars driven by stars Kevin Harvick and Denny Hamlin. He can’t remember whether he saw the Victory Junction Chevrolet owned by Richard Petty with its iconic number 43 and the name of its driver — Bubba Wallace. But, to his surprise, he saw many people of color in the pit crews.

Nashville reminds Moses of Washington, D.C., when he arrived there in 1996 — bursting with potential. He faces perhaps his greatest challenge as a sports entrepreneur: Interest in stock car racing had slid significantly before the pandemic, and the track has been idle for 10 years (Jon Morgan/AP Images for Carolina Alumni Review)

As he passed the start/finish line, it happened — pop! — his flashbulb moment of illuminating clarity.

“I see this older gentleman who’s in his 70s and his wife. He looks like what most of us would think is the somewhat stereotypical NASCAR fan. His skin is leathery. He’s got a lot of sun. He’s got a baseball hat with favorite driver on it. He’s in a T-shirt and jeans. His wife looks similar. He is holding the hand of a small brown child, a Black kid, a boy. His wife is holding the hand of small brown child, a little Black girl. I’m assuming, as I look at this, that those are probably their grandkids. It was just kind of this epiphany of: ‘Hey, let’s not assume what everyone assumes this sport is and what its fan base is. It isn’t what you think. There’s more here than what meets the eye.’ ”

The welcoming

Nashville reminds Moses of Washington, D.C., when he arrived there in 1996 — a city bursting with growth and potential. “Our job is to make certain the big top is ready,” said Moses, who notes the speedway’s 1,000-acre footprint makes it ideal for year-round happenings. “To someone like me who has curated and hosted events, you can imagine my brain is popping with ideas. Let me at it.”

Scheduled for June 20, the Ally 400 will be the Nashville area’s first NASCAR Cup Series race in nearly 40 years. A timer on the track’s website counts down the days, hours, minutes and seconds until the green flag drops.

On race day, will racial tension be an issue?

“The biggest challenge Moses will face is he’s taking a track that’s been dormant for 10 years and trying to attract a crowd to a track that was never capable of getting a Cup date in the first place,” said Tom Bowles, the editor-in-chief of the racing news website Frontstretch.

“I don’t see race as an issue in Nashville. Some people have the wrong impression that NASCAR fans are beer-swigging and have a fascist attitude,” added Jerry Bonkowski, who has covered the sport for NBC News and USA Today for 20 years. He said he has seen “blatant displays” of huge Confederate flags only a few times.

“NASCAR’s on its way back,” Bonkowski said. “The people who run NASCAR understand the challenges they face and are meeting them head-on to make people understand.”

The organization has pounced when its public faces have breached the standards. Last spring, when the Cup circuit was limited by the virus to a sophisticated video racing game, rising star Kyle Larson used the n-word on his radio, and the TV broadcast picked it up. Larson immediately found himself on the outside, suspended and abandoned by his sponsors. More recently, a driver in NASCAR’s truck series posted a photo of a swastika he had drawn, and he was banished that day.

On the morning of the race at which the noose was found in Wallace’s garage stall, all the drivers and pit crews came together in an emotional televised show of support for Wallace.

“NASCAR is trying to become more progressive in trying to shed some of its old connections to a more racist ideology that gripped the sport through as late as the 1980s and 1990s,” says Bowles, who also believes that “NASCAR is headed in the right direction.” Michael Jordan’s announcement in September that he and Hamlin would co-own a racing team in 2021 and that Wallace will drive for them did much to reverse negative publicity from the noose incident, Bowles said.

True to his embracing nature, Moses welcomes everyone to his speedway.

“In meeting strangers, you have opportunity to find common ground with somebody you never would have expected to. That always fortifies my faith in humanity. You find things in common, share a laugh. You walk away feeling there’s a chance we may be able to make this thing work down here.”

— Erik Moses ’93

“I don’t necessarily think being a quote unquote ‘redneck’ is necessarily a negative thing. They aren’t necessarily racists. The negative things we attribute to that persona may not always be present. Maybe in that person’s head a redneck is somebody who likes to fish, hunt, drive things fast, listen to country music and drink some whiskey, and you know what? I might raise my hand on most of those things, too.”

Moses also confesses — in NASCAR’s true rowdy spirit, as Tom Wolfe might have put it — that since moving to Tennessee, “I find myself on a bunch of country roads, and I’ve been driving a little bit more aggressively.”

He knows NASCAR’s decision to ban the Confederate flag will “go a long way” toward drawing more diverse fans. “People have told me I’m a symbol of what is possible,” he said. “I think having a symbol of Southern heritage or things about being a Southerner that you like is legitimate. It just shouldn’t be that symbol. It should be something else.”

With a hint of self-promotional mischief in his voice, Moses asks: “You know what I think? I think NASCAR should be the symbol, because of the Junior Johnsons of the world and the Pettys of the world. Wouldn’t it be great if NASCAR was that symbol, if we could all get behind that? Oh, my goodness, if Bubba starts winning or if Suarez starts winning or other people like that start winning? We see what happened in golf with Tiger. We see what happened in tennis with the Williams sisters. People need to feel welcome.”

—Freelance writer George Spencer is based in Hillsborough.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.