Timelessness on His Hands

Posted on July 7, 2017

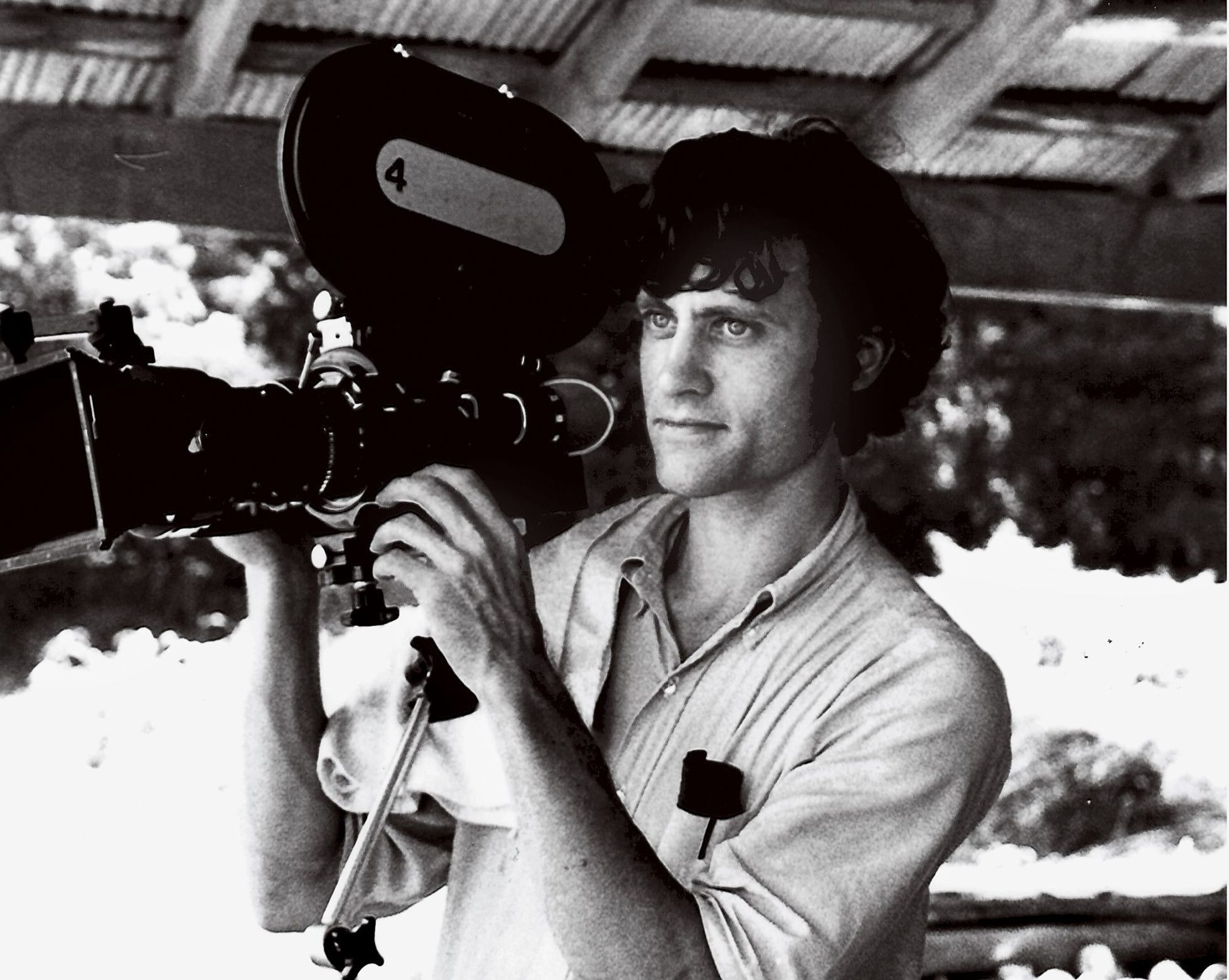

Bill Ferris filming a blues musician in 1973. (Photo by Hester Magnuson)

Drawn to the stories, music and pictures in his own backyard, Bill Ferris methodically built a priceless archive of Southern folklore.

by Barry Yeoman

The white folklorist pulled his Chevy Nova up to a sharecropper’s shack on a Mississippi farm. He had heard that its tenant, an African-American man named James “Black Boy” Hughes, played blues guitar, and he was eager to record some music. But this was 1968, and there were certain protocols to follow. So Bill Ferris already had gotten permission from Hughes’ white boss.

Arriving on a hot June afternoon — his metal toolbox filled with film, microphones, extension cords and audio tapes — Ferris found the white farmer and some of his friends standing outside their trucks, inspecting a rifle.

The farmer called Hughes’ name. Hearing no response, he lobbed some rocks at the musician’s tin roof. Hughes, sinewy and snaggle-toothed, emerged from the shack and performed a few obligatory tunes on the porch, then said his hands were too wet and begged off. Figuring the show was over, the farmer and his friends disappeared.

That might have been that, except that Ferris and Hughes agreed to meet again, away from the boss’s suspicious eyes.

Hughes played for hours — a powerful, guttural blues — and chatted uncharitably about his boss as the whiskey flowed into the night and this long-haired 26-year-old fellow Mississippian photographed and recorded. Hughes told him to come back any time, without white authorization, and to spend the night. “Come on in. If I make coffee, drink coffee. If I eat a piece of bread, eat bread,” he said. “Any time you drive to my house and I ain’t there, stay right there ’til I come. Don’t leave. I’m coming back.”

Ferris, who was working on his doctorate from the University of Pennsylvania, couldn’t have known what would come of that night — that a half-century later, those pictures and reel-to-reel tapes would land in a 173,000-item archive bearing his name within UNC’s Southern Folklife Collection; that he would become one of the world’s foremost authorities on that subject; that he would leave the comfort of one of its choice enclaves only to lend his reputation to another.

His sole immediate resolution was that he would never again consult with white intermediaries before entering an African-American community.

This was a dangerous decision, given Mississippi’s climate of racial terror and violence, and he knew it. “It was a Jim Crow system, a caste system,” he says today. “It was just a given: You could kill a black person, and it was not considered a crime. If you were perceived, as a white person, of trying to challenge that system, you were expendable, too.”

Throughout his career — teaching at three other universities, heading the National Endowment for the Humanities and finally, in 2002, arriving at UNC — Ferris, now 75, often has veered widely from accepted protocol. Just as he flouted the racial code of the 1960s, he went on to challenge some of the conventions of folklore and, more broadly, academia. He has stripped documentary films of their scholarly talking heads; brought bluesman B.B. King into an Ivy League classroom; and honored Goo Goo Clusters in the Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, which he co-edited. He dressed as Elvis Presley to celebrate the encyclopedia’s release.

The past few years have turned out to be some of Ferris’ most prolific, as he has reviewed and repackaged his old fieldwork. In 2009, UNC Press published Give My Poor Heart Ease, a 300-page volume of oral histories and photos of Mississippi blues and gospel musicians he interviewed in the 1960s and ’70s. The book is accompanied by a CD of his recordings and a DVD that takes viewers into barbershops, churches and a prison.

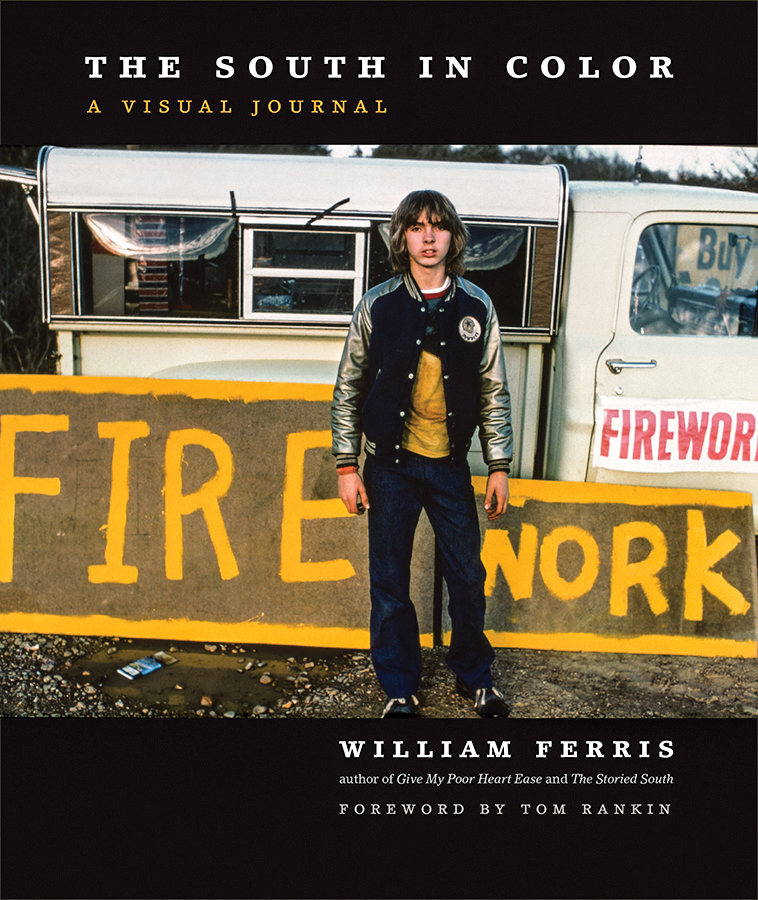

The South in Color: A Visual Journey

That was followed by The Storied South, his 2013 book of interviews with writers, artists and scholars. Last year, he compiled his color photographs into The South in Color, which feels particularly intimate: It includes Ferris’ boyhood farm, the black church he used to visit and numerous portraits in which the subjects, black and white, look unflinchingly into his camera. On tap are a larger book of black-and-white photos and, eventually, a memoir.

He has worked to convince Americans that their family photos and recordings are legitimate historic documents worth preserving. “He doesn’t see knowledge as only the property of the formally educated,” said Tom Rankin ’84 (MA), who directs Duke University’s graduate program in experimental and documentary arts.

Ferris’ fascination with vernacular culture, and his insistence on accessible presentation, have at times made traditionalists bristle. But lately he has found his views vindicated.

“The academic world,” Rankin said, “has caught up.” And Ferris has built an intellectual authority custom-made for this historical moment: President Donald Trump’s proposed defunding of the humanities agency he used to head.

Poignant pictures

In the Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964, a statewide voter-registration drive culminated in the murders of three civil rights workers near the town of Philadelphia. Two hours away, in Vicksburg, things also were tense. A bomb was tossed through the window of a black cafe. A black milkman’s assistant lost his job because he attended civil rights trainings. African-American schoolteachers laid low out of fear of being fired. Later that year, a hurled stick of dynamite would turn Freedom House, the local movement school and community center, to rubble.

Fifteen-year-old Elizabeth Guider didn’t know much about politics, but she did hear her white elders disparage the growing interracial movement in her hometown of Vicksburg.

“I would see blacks and whites in the same station wagon, and people threw rocks at those cars,” she recalled. She went to a racial equality meeting, on the sly. “My parents would have flipped out.”

“There’s an intimacy [Bill] fosters: When you’re with him, he’s talking directly to you,

and you’re the most important person in the world.”

–Randall Kenan ’85

What Guider, now a journalist and novelist, recalls most clearly was the mutual respect she witnessed. “It was the first time that I saw blacks and whites talking as equals,” she said. “And it was all led by Billy [Ferris] and his father.” The younger Ferris, at the time, was 22.

The Ferrises lived in Broadacres, a bayou-riven farm outside Vicksburg, where they raised cattle and grew soybeans and cotton. “The farm was something of a bubble,” Ferris said.

As a child, he played with the children of black farmworkers and visited a black church, where he learned hymns that parishioners had committed to memory. His first taste of segregation came when he was bused to Jefferson Davis Academy, an all-white public school, at age 5, while his African-American playmates studied at a one-room schoolhouse on the farm. “This is not right. It’s not fair,” he recalled telling his parents.

“It’s the way things are,” they replied.

When he was 12, Ferris received a Kodak Brownie camera as a gift. The Brownie was a technological breakthrough of sorts — now anybody could take pictures without a gaggle of sophisticated equipment. He photographed his farm surroundings: first his grandmother’s Christmas dinner, then the bayou baptism of several African-American children. Soon afterward, he began recording hymns from the black church and interviewing families — unwittingly laying the groundwork for his career.

Jim Steed, 1974. (Photo by Bill Ferris)

Chronicling those lives, for Ferris, became inseparable from defending them. During high school, he attended a Massachusetts boarding school where the headmaster preached about racial justice. As an undergraduate at Davidson College — he graduated in 1964, just before that Vicksburg meeting — he wrote editorials and helped organize protest marches.

“Once he was awake to the world that he lived in, and what it meant to be a just Southerner, then he was on that train,” said his wife, Marcie Cohen Ferris, a professor of American studies at UNC. “He wasn’t going to get off.”

He saw the repercussions up close. At Davidson, a cherry bomb was planted in Ferris’ room and black pepper sprinkled on his bed. A Ku Klux Klan poster was tacked to a fencepost on his family’s farm. But he persisted, buoyed by moral conviction and music. At one civil rights conference in Illinois, during a song circle, Ferris stood with his arm around Bernice Johnson Reagon, the venerated founding member of the Southern Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Freedom Singers (and later co-founder of Sweet Honey in the Rock).

“Her whole body just shook with the power of her voice, singing We Shall Overcome,” he recalled. “Those are moments that are life-changing.”

‘You should be in folklore’

Ferris initially thought he’d honor his childhood neighbors as a fiction writer. Reading Southern authors like William Faulkner discouraged him. “There was no way I could hold a candle to them.”

Similarly, taking up farm work didn’t seem like an option. “It was like facing Faulkner when I faced my father in the tractor shed. I just felt all thumbs.”

William Ferris Sr., 1963. (Photo by Bill Ferris)

He didn’t know he could make money recording his neighbors’ stories and music until he met folk-literature scholar Francis Utley during a fellowship in Ireland in 1965.

“You should be in folklore,” Utley advised him. “What’s that?” he asked.

Soon Ferris was enrolled at Penn, lugging a box of his Mississippi archives into the office of his doctoral adviser, folklorist Kenneth Goldstein. “That, my boy, will be your dissertation,” Goldstein said.

During every campus break, Ferris headed south to record, photograph and film musicians and storytellers from the Mississippi Delta. Over the years, his work fanned out. In the 1970s, teaching first at Mississippi’s Jackson State University and then at Yale University, he spent years interviewing Ray Lum, a Vicksburg mule trader. He talked with Southern authors like Eudora Welty and Alice Walker. He invited B.B. King to play for his Yale class, then did a series of interviews in which the bluesman bared his soul about the deep loneliness that stemmed from spending much of his childhood without parents.

“I feel close to anybody that seems to take interest in me as a person,” King told Ferris. “A lot of times it seems to me that I’m crying out to people, ‘Hey. I’m me. I would like to be with you. I would like to share whatever I have with you.’ ”

Colleagues say it’s no accident that Ferris’ subjects open up. “He’s not up on high,” said author Randall Kenan ’85, a professor of English at UNC. “He’s down on the ground with them, tending hogs and going to the juke joints and laughing. There’s an intimacy he fosters: When you’re with him, he’s talking directly to you, and you’re the most important person in the world.”

Ferris gave his subjects center stage. In 1978, he and Judy Peiser (with whom he founded the Memphis-based Center for Southern Folklore) produced the four-minute film Hush Hoggies Hush, about the Rev. Tom Johnson, a Mississippi farmer who had trained his pigs to pause for a prayer before eating. There’s no narrator, no scholars — just Johnson dispensing wisdom and training the pigs, plus a bed of jaunty music.

The Journal of American Folklore gave Hoggies a tepid review: “Something that falls more within the realm of comedy than the documentation of a folk art or folklife activity.” Reviewer Nick Spitzer, a Louisiana folklorist, asked, “Does [Johnson] interpret the humor as potential chastisement for men who merely ‘go through the motions’ when addressing the Lord, like animals incapable of symbolic thought?”

Ferris (who calls Spitzer a friend) says he has grown accustomed to feedback like this. “I’ve always been criticized as not being a serious scholar,” he said, adding that his choices in films like Hoggies were deliberate. “To put myself or an ‘expert’ on the screen would be to minimize the power of that moment. Theory changes with each generation. But the power of the voices of the people grow more important over time.”

Home to Mississippi

The precursor to Ferris’ work in Chapel Hill came in the late 1970s, when the University of Mississippi lured him from Yale to lead its new Center for the Study of Southern Culture.

Mississippi, at the time, was just a decade removed from the peak of the civil rights movement. The Philadelphia murders, the assassination of NAACP activist Medgar Evers, the “state sovereignty commission” that spied on “race agitators” — these were all recent memories.

Ferris wrote that author Eudora Welty’s vision “helped me frame my work as a folklorist.” (Photo by Bill Ferris)

Ferris seemed well-positioned to create a Southern culture program within Mississippi’s flagship university at Oxford. He took a voracious approach to building the center during 18 years there, assembling a high-powered board, including authors Eudora Welty and Toni Morrison. He acquired the research collection of his adviser Goldstein — “the finest folklore library in private hands,” he said — which, along with B.B. King’s record collection, helped build a blues archive that now holds 60,000 recordings. The center held civil rights symposia; capitalized on the Russian love of Faulkner to create a Cold War-era partnership with the Moscow-based Gorky Institute of World Literature; and compiled the 1,600-page Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, published by UNC Press.

Ferris built relationships with scholars and producers of both high and low culture.

“People would come through Oxford, and he was like Noah with the ark,” said Duke’s Rankin, who overlapped him there. “If he could add two more of a different way of knowing, he would.”

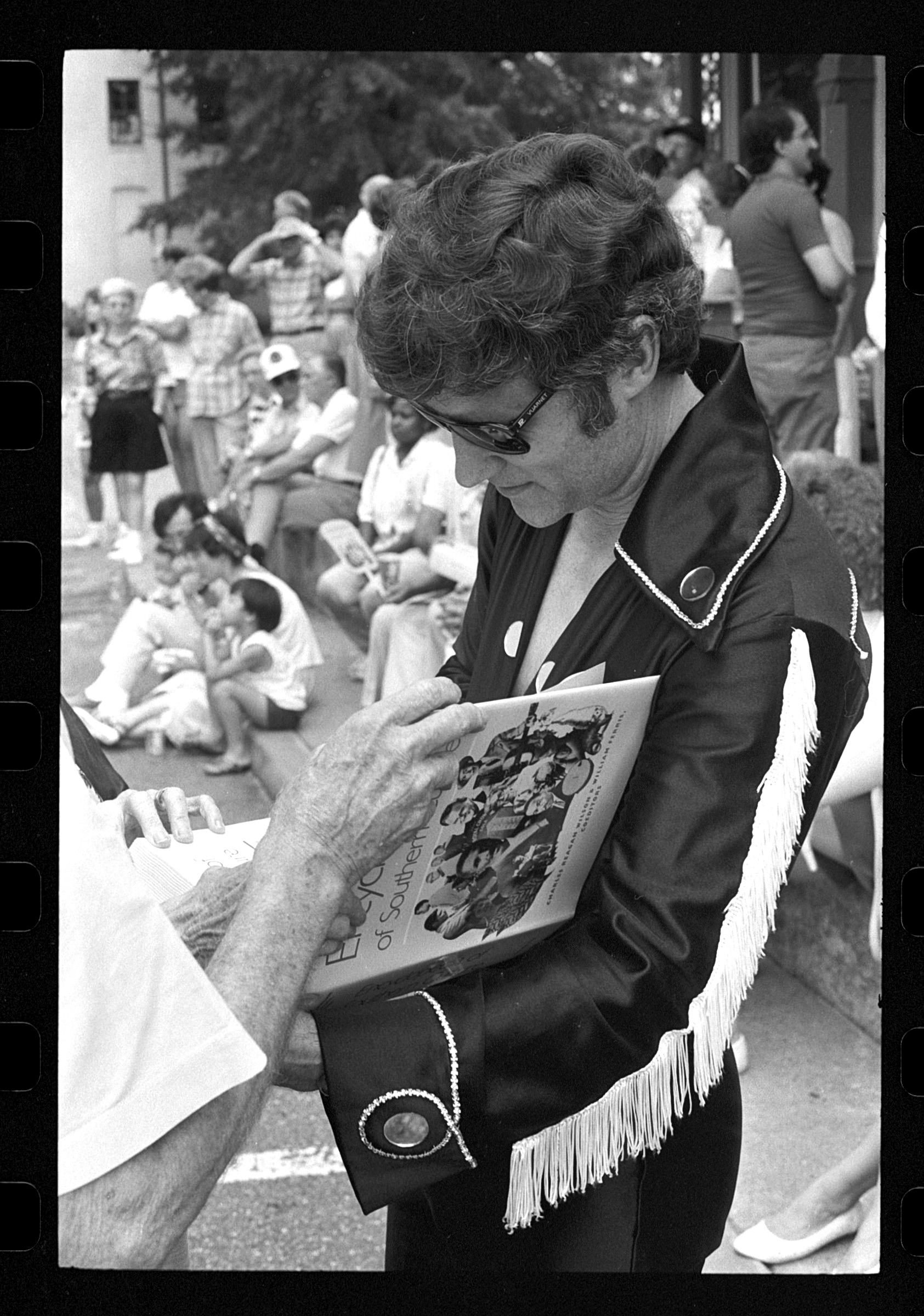

Bill Ferris dresses as Elvis during the “Encycloparty” in Oxford, Mississippi, celebrating the publication of the Encyclopedia of Southern Culture. (Photo by Tom Rankin)

Not everyone countenanced this broad approach. The national academic culture wars — which inspired art critic Hilton Kramer to call the study of popular culture a “spirit-destroying menace to the life of the mind itself” — had hit Mississippi, too.

“He got a lot of resistance from faculty,” Ann Abadie, the center’s former associate director, said of Ferris. Some objected to the center’s acquiring the popular magazine Living Blues, which until then was based in Chicago. “Publishing a little magazine was not quite proper,” Abadie said, quoting critics. “It’s fine off-campus. But it’s not a thing one does at a respectable university.”

More suspect, to some, were the two Elvis conferences Ferris helped organize starting in 1995, which the Los Angeles Times called “the latest salvo in a national battle about the nature of scholarship.” They included academic papers but also performances by impersonators like Elvis Herselvis. And they ticked off classicists, who were still arguing whether authors such as Maya Angelou and Alice Walker, much less “the King,” belonged in the Western canon.

“The professors organizing this jamboree should resign their positions,” said Stephen Balch, then president of the National Association of Scholars, “or at least set up a rotational basis where they teach one semester and the Elvis impersonators get the other.”

In 1997, Ole Miss withdrew its support for the conference. By then, Ferris was on to his next adventure.

A populist in Washington

When an aide to President Bill Clinton called Ferris in 1996 to gauge his interest in chairing the National Endowment for the Humanities, “I thought maybe she had lost her mind,” he recalled. “I looked at NEH as a sacred world, far above any place I would ever know.”

Federal arts and humanities funding was under siege in the ’90s. A handful of artists supported by the National Endowment for the Arts — most famously Robert Mapplethorpe, whose photographs depicted sexual fetishes — had drawn congressional disfavor. Sen. Jesse Helms of North Carolina described their work as “disgusting, insulting, revolting garbage” and helped lead the revolt that clipped NEA’s budget. NEH, caught up in its own debate about history and multiculturalism, took a financial hit, too. “Some folks wanted to throw all the cultural agencies into the same bucket,” said Michael Bagley ’81, whom Ferris tapped to head NEH’s congressional affairs office.

Ferris’ expansive view of culture, which sometimes raised hackles in Mississippi, served him well during his four years in D.C. If a lawmaker was interested in ranching, Ferris would talk about Lum, the mule trader. With Helms, he discussed country music. “Some of the Mountain West senators originally were inclined to want to cut the budget,” Bagley said. “Bill talked to them about how grants supporting cowboy culture in their states helped them.”

George Will, the conservative columnist, suggested that Ferris and his NEA counterpart, William Ivey, were “defanging Republicans by becoming populist, and perhaps philistine.” To Ferris, this inclusive approach was a necessary corrective. “There has been a perception that the humanities is owned and controlled by the Ivy Leagues,” Ferris said. There’s so little money to begin with, but much of that went to the wealthiest institutions: Harvard, New York Public Library, Yale. “There was very little left for the local libraries, local museums, high school teachers.”

Ferris worked to shift the emphasis, with regional humanities centers, flat-board exhibits that could travel to places without museums, and seed grants to small filmmakers. The NEH published a guide to conserving family photos and capturing grandparents’ stories. “He did not make those Yale and Harvard scholars feel like they were being pushed aside,” Bagley said. “He simply made sure there was a balance.”

Living in D.C., Ferris never really assimilated. Colleagues say his outsiderness served him well. Before one Washington speech, he told his chief of staff, Ann Orr, that he intended to play his guitar and sing to the suit-and-tie crowd. “I was horrified,” she said. “That is not the way Washington politicians conduct their business. I sat in the back and watched him with fear and trembling. He started playing his guitar — and people loved him. He told stories of the South while he was performing, and it was just infectious.”

More discerning lenses

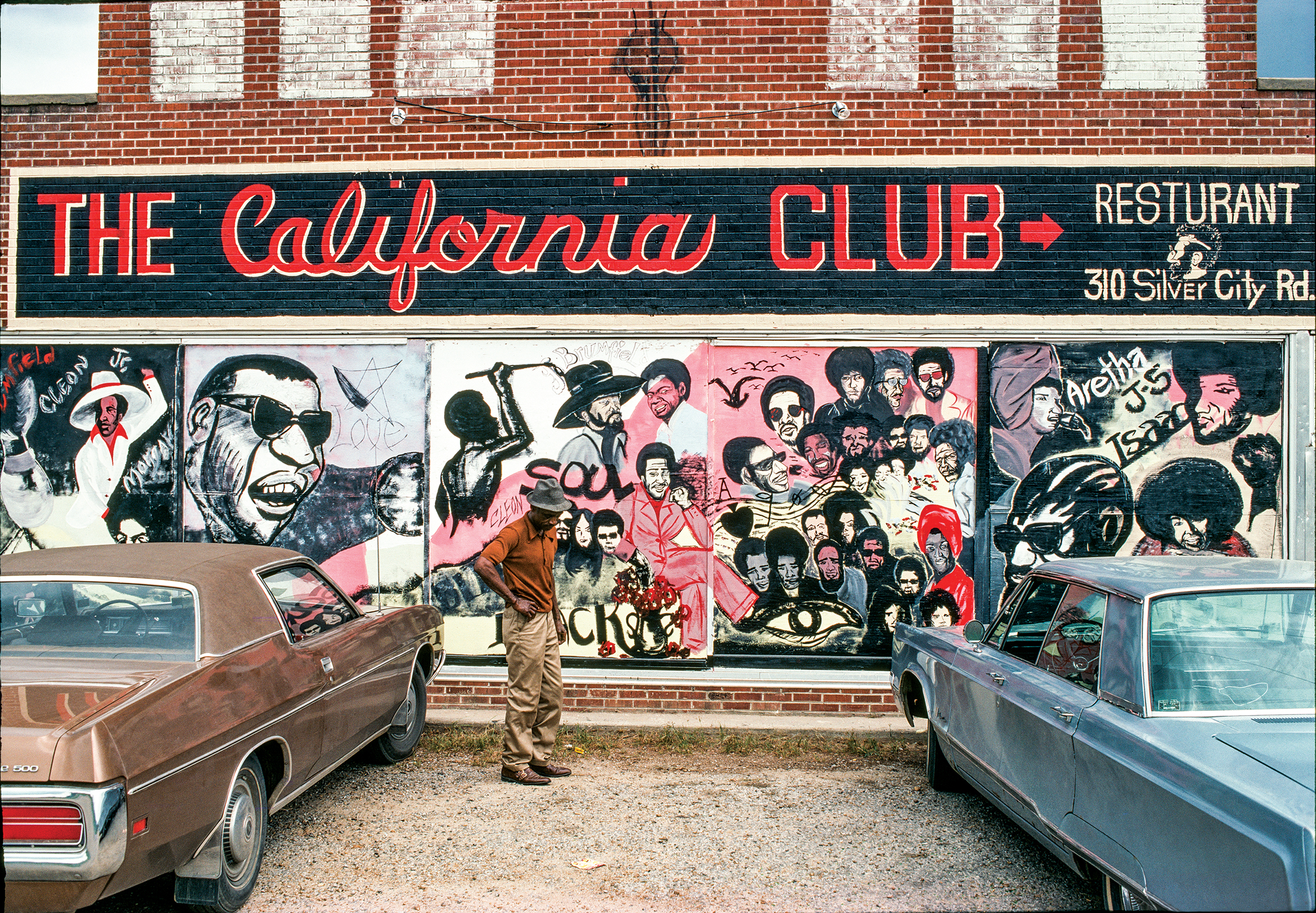

The California Club, 1975. (Photo by Bill Ferris)

Fifteen years removed from the D.C. scrum, Ferris has never lost sight of the connections among culture, money and politics. In 2008, he used Barack Obama’s presidential victory to call for a Cabinet-level culture secretary who could advocate for financial and political support. (The suggestion, offered in a New York Times column, went unheeded.) Now, nine years later, he’s speaking out against a potential worst-case public-funding scenario.

In May, President Trump released a budget blueprint that calls for eventually shutting down the NEH, starting with a 72 percent cut in 2018. Also facing elimination are the NEA and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. This aligns the president with free-market groups such as the Heritage Foundation, which says taxpayers “should not be forced to pay for plays, paintings, pageants and scholarly journals.” While Congress likely won’t adopt Trump’s budget in toto, the document makes clear the administration’s long-term priorities.

Ferris says this is the opposite of what needs to happen — that the government, in fact, needs to deepen its investment.

“The humanities and arts are how we are known throughout the world. They are why we are a beloved country in spite of ourselves. Our politics, a century from now, will be forgotten. The battles will be vaguely remembered. But the great contributions of our artists and writers and filmmakers will loom more brightly than ever as the beacons of who we are and who we were. To turn your back on this is unthinkable, unforgivable.

“The meager budgets of the endowments I call a widow’s mite. It’s a few cents out of the pocket of every American that have a transforming effect. In every library, in every classroom, in every home, they bring us light; they make our lives bearable and give us hope for the future. So when we say we want to make America great again, let’s do it. Let’s expand those budgets.”

‘The humanities and arts are how we are known throughout the world. They are why we are a beloved country in spite of ourselves. Our politics, a century from now, will be forgotten…but the great contributions of our artists and writers and filmmakers will loom more brightly than ever as the beacons of who we are and who we were. To turn your back on this is unthinkable, unforgivable.’

–Bill Ferris

Ferris now speaks from the perch of UNC’s Center for the Study of the American South. When the University offered both him and his wife positions, “it was a no-brainer,” he said. “It’s the most important university in the world for study of the South.”

In Chapel Hill, spared heavy administrative responsibilities, Ferris has focused on teaching, producing books and helping build the University’s immense Southern studies resources. He has assisted Wilson Library in acquiring archives and finding resources to digitize them — making them much more accessible to the public.

His own archives, housed in the library’s Southern Folklife Collection, cover everything from auctioneers to the blues to the Klan. There are photos of weddings, gravestones and store mannequins; digitized recordings of religious services; and two folders on mules in American history.

Office with a porch swing: At Carolina, Ferris is helping grow an already immense archive. (Photo by Anna Routh Barzin ’07)

Ferris also is focusing on new teaching technologies. Working with the Friday Center, he has produced an online course on Southern stories, art and music, which he says has reached more students than he’s taught face-to-face. He’s collaborating with the Morehead Planetarium and Science Center to produce a full-dome 28-minute production on the American South, narrated by actor Morgan Freeman. Ferris says the presentation will be available to other domed theaters and will be accompanied by a website for K-12 schoolchildren.

Then there are his informal job titles: ambassador, cheerleader, connector, dispenser of small kindnesses. In those roles, Ferris’ laser-like focus on whomever he’s talking with and his embrace of young scholars and artists are legendary. “He’s the best gateway drug into folklore, the South, documentary,” Rankin said. “He tells you things that you know are not true, like you’re the greatest thing ever to come through [town].” Back when Rankin was a young folklorist, he said, “there were times I thought, ‘Oh, come on. Cut the hyperbole.’ But that optimism — I’ve come to see its power.”

Bruce Jackson, a professor of American culture at the University of Buffalo and a Ferris colleague for more than 40 years, notes that Ferris’ recent creative explosion also comes from reaching a stage in his life at which he can curate old work through more discerning lenses.

“We never know a story when we’re in the middle of it,” Jackson said. Speaking of The South in Color, he explained: “Bill was making those pictures, and then he looked at them, and he realized there was a story there that he was a participant in, but which he could not have seen at the time, because it didn’t exist until the effect happened, and the effect was getting old enough to look back on them and see that the trajectory that he described was bigger than the individual incidents in which they were made.”

Barry Yeoman is a freelance writer based in Durham.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.