Where You Can’t Study, and Where You Can

The choice for people of the Baha’i faith is endure quietly or leave. They bring an extraordinary commitment to places like Chapel Hill.

by Mark Derewicz

Sepehr (Anna Routh Barzin ’07)

Shabnam (Anna Routh Barzin ’07)

CHAPEL HILL, September 2010 — Shabnam Ranjbar and Sepehr Kaiser enter Tarrson Hall, glancing to the Carolina blue sky purposefully, like a ritual. They’re married, and they’re students.

Azadeh (Anna Routh Barzin ’07)

Down the hall walks Azadeh Rohanian-Perry. She’s a clinic coordinator and dental assistant supervisor at UNC. Like Shabnam and Sepehr, she is from Iran and, as they did, she has found a home at UNC’s School of Dentistry.

When they see each other, they smile and hug.

To them, Carolina blue is less a point of pride and more a symbol of freedom.

“It reminds us that we can go higher and higher,” Shabnam said. “Thanks to Carolina, we are allowed to succeed.”

At UNC, they can come and go as they please. They can read books, study what they choose and pursue education and careers based on their own aspiration. In Iran, they could not. There, to own academic books was to risk arrest. They couldn’t gather to learn about Shakespeare or calculus or dentistry without fear of their homes being ransacked and their computers and books being confiscated.

The reason for all of that is because they are members of the Baha’i faith, a worldwide religion that originated in Iran. According to eyewitness accounts, international human rights organizations and the governments of the world, Baha’is are regularly denied basic rights, tortured, “disappeared” and sometimes killed. Muslim clerics and religious judges consider Baha’is to be “unclean” and “spreaders of corruption on Earth,” and authorities have arrested Baha’is for allegedly “spying for Israel.”

Baha’is are members of a religion born from an Islamic society, much as Christianity stemmed from a Judaic world. They say that their chief concern is to foster unity among people, nations and religions and to promote universal human rights. The religious and Quranic interpretations that have spawned Baha’i persecution are complex, but the real-life results are not. Denied rights to education and steady employment, Baha’is either endure quietly while risking imprisonment or they leave.

Shabnam, Sepehr and Azadeh left under very different circumstances. None of them regrets it.

“Every day at UNC, I would think about how incredible it is to study here,” said Shabnam ’12 (DDS). “Even the color of the sky reminds me of it. We were encouraged here. The faculty pushed us so we could succeed. It wasn’t like this in Iran, and not just because I’m a Baha’i, but because I’m a woman.”

“I don’t think there was one day we took our education for granted,” said Sepehr ’09 (’13 DDS). “Dental school can be incredibly difficult at times, and the workload becomes like nightmare for students, but we felt so fortunate just to be here that we were happy to work hard to achieve our dreams.”

Shabnam and Sepehr left Iran with passports and plane tickets to Austria. They came to the U.S. through normal visa processing and are now citizens.

In contrast, Azadeh Rohanian-Perry was an asylum seeker, and her harrowing story stems from Iran’s deep and deadly modern history that still haunts her and her family.

SHIRAZ, IRAN, October 1982 — A 16-year-old girl named Mona Mahmudnizhad was arrested for teaching the history of the Baha’i faith to young Baha’i children. She was held in prison for eight months.

With dozens of other Baha’is, including her father, Mona was sentenced to death. She was one of 10 women who were told that if they publicly recanted their faith, they would be spared. They refused. The 10 were led to a polo field where there were gallows. Awaiting her fate, Mona grabbed the executioner’s hands and lovingly kissed them. Then she kissed the rope and put it around her own neck. Moments later, she was martyred.

Azadeh was a few hundred miles to the north when she heard the news of her friend’s death. She was shocked: Her own sister had taught and organized Baha’i youth just as Mona had, and she was aware of Baha’is disappearing, of friends being beaten, and relatives harassed. Her sister’s house and the homes of 300 other Baha’is were burned to the ground in one day. Later, more homes were burned throughout the country.

‘When I left Iran, my dad told me wherever I go, that will be my home and that will be my language. He told me, “You have to move on with your life. Hope is good, but don’t just think constantly about trying to go back. Don’t have two lives. Let go, and start your new life.” ’

Azadeh

SHIRAZ, IRAN, June 1987 — Azadeh was 19 when she decided to leave Iran, mostly because her parents wanted her to have a better life.

“Ever since the 1979 revolution, my father was heartbroken about what happened to his country and to Baha’is,” Azadeh said. “My parents worried what might happen to me because they knew I wanted to work with kids. And they knew I’d have no opportunities. They urged me to go.”

She packed two large suitcases with clothes and supplies and, along with 15 others, paid smugglers to be driven in an open-bed truck across southern Iran to Pakistan. During one stretch, they walked for hours at night. At a border village, the smugglers put them in a dark room in a small house and told them not to leave.

“Other smugglers were there smuggling guns and drugs,” Azadeh said. “And we were told they’d take us — the women — if they found out we were there. All night, we didn’t make a sound.”

The trip to Lahore, Pakistan, was supposed to take two days. It took 10. At the end, the smugglers robbed the group. “They took everything,” Azadeh said.

Two weeks after arriving in Lahore, Azadeh was walking home from a grocery store with her sister-in-law, Firuzeh, when a car swerved onto the sidewalk, knocking Firuzeh to the ground and pinning Azadeh under the car. She was dragged for more than 100 yards before the car slammed into a tree.

Firuzeh screamed and passed out. Azadeh lay in a ditch, unable to move as men at the scene refused to help her. In that neighborhood, Muslim men do not touch women to whom they are not related. Two Baha’i boys came running and brought her, still conscious, to the hospital in the back of a truck.

TEHRAN, 2002 — Shabnam, a whip-smart 21-year-old who wanted to work in health care, didn’t want to leave her country. So many Baha’is were suffering; why, she thought, should she be allowed to leave them? But her parents and only sister had had enough. Worn down by two decades of oppression, the Ranjbar family wanted a new life.

“My mother would cry every night,” Shabnam said. “Our Baha’i brothers and sisters were being killed. The government was plowing under Baha’i cemeteries and destroying holy places. They were kicking kids out of university and jailing the ones who spoke out about it. It was incredibly sad. It still is. It hasn’t stopped.”

Shabnam’s father, an electrical engineer for the public utility before the revolution, scraped together a living fixing broken refrigerators and electronics. Government officials targeted his business.

“My father told me, ‘There is nothing here for us, especially you,’ ” Shabnam said. “ ‘You are a woman and a Baha’i. You will not be allowed to get the education you deserve, to use your talents or to follow your dreams. Your fortunes will depend on whom you marry. This is not what I want for you.’ ”

Shabnam realized that if she didn’t leave Iran, then her family wouldn’t leave either.

“I couldn’t be the one who kept them in Iran,” she said. “So I agreed to leave.”

They bought tickets to Vienna with no plans to return.

When she arrived, she immediately went to a study circle — similar to a Bible study — something that is outlawed in Iran. There she met Sepehr, who had left Iran three months earlier.

For years, Sepehr had refused to leave Iran. In his experience, he saw most Muslims as good people.

“Of course, I wanted an education, but leaving the country wasn’t as simple as just seeking better opportunities,” Sepehr said. “If it was just about that, I would’ve left years before I did; it’s deeper than that. At some point, you feel disabled. They take your life. They continually try to crush your spirit. You feel like you have nothing to do.”

At age 26, in 2002, Sepehr decided to leave. In Austria, he and Shabnam became friends. Within a year, they were engaged. They both wanted to come to the U.S., and they chose Chapel Hill, where Sepehr had family and because the Triangle is noted for its educational opportunities — and it has a vibrant Baha’i community that focuses on serving the greater community, something they were prohibited from doing in their home country.

They set their sights on attending Carolina.

LAHORE, PAKISTAN, June 1987 — Azadeh lay in a hospital bed, her face burning hot; she wanted cold water, and the nurse, who spoke Urdu, not Farsi, pointed to the bathroom. Azadeh got up, took a few steps, and then collapsed. Ten minutes later, nurses found her unconscious, sprawled on the floor. She had a broken back.

Doctors suspected she’d never walk again. They put her in a full body cast, and for four months she lay in bed motionless, in the heat of the Pakistani summer. She couldn’t feed herself or get to the bathroom.

“All I did was pray,” she said. “I just laid there and prayed to God. I prayed for healing and my family. I prayed for the Baha’is in Iran. I prayed for world unity. I prayed a lot.”

At the end of five months, as Azadeh’s 10-month-old nephew learned to walk, so did she. With one arm draped over her brother’s shoulder and her other arm wrapped around her sister-in-law, Azadeh hobbled across the room, struggling to keep her head up because her neck was so weak.

A month later, she could walk gingerly on her own, but the pain would never fully leave her.

For the next year, seven days a week, Azadeh worked with Baha’i youth, teaching them virtues, arts and religion, including lessons about the spiritual oneness of all religions. One irony of Baha’i persecution is that Baha’is believe in the validity of Mohammed, just as they believe in the divine stations of Jesus, Moses, the Buddha and other major prophets, which they refer to as “Manifestations of God.” But they also consider the founder of the Baha’i faith — Baha’u’llah — to be the latest Manifestation, the one who was tasked with uniting the peoples of the world based on the spiritual virtues inherent in all religions. The fact that he claimed this station in the 1860s — well after Mohammed lived — is considered heresy in some circles, including the highest ring of leadership in Iran.

After 19 months in Pakistan, Azadeh was able to move to Australia, where four of her siblings had established residency. She would never return to Pakistan or Iran.

“When I left Iran, my dad told me wherever I go, that will be my home and that will be my language,” Azadeh said. “He told me, ‘You have to move on with your life. Hope is good, but don’t just think constantly about trying to go back. Don’t have two lives. Let go, and start your new life.’ ”

Azadeh’s father died while she recuperated in Lahore. In the years following her travails in Pakistan, the authorities in Iran would make letting go of her past and her family harder than she had thought.

Before Azadeh Rohanian and Mark Perry met, they were connected in an unusual way: Mark had written a play about a girl who was martyred for teaching about the Baha’i faith, and Azadeh had been one of the girl’s friends. (Photo by Anna Routh Barzin ’07)

HAIFA, ISRAEL, June 2000 — On Mount Carmel, home to the World Center of the Baha’i faith and where Baha’is from around the world gather for pilgrimage, Azadeh met a young American named Mark Perry. In the presence of the Baha’i faith’s sacred holy places, Mark and Azadeh prayed together on their final day in Haifa. Mark told Azadeh about a play he had written. It was called A Dress for Mona.

Azadeh smiled and said, “Mona? I knew Mona. I was her friend.”

“You knew her?”

“Yes. I was her friend. I knew her and her father and her entire family. Long ago.”

Mark could hardly believe the coincidence. He had written the play as part of his graduate work at the University of Iowa, but during a writing workshop his fellow students told him the play read like a gospel about a saint because Mark had struggled to portray Mona as a real person, as a product of her culture, as strong but not impervious to fear or pain. When he met Azadeh, he realized he had a chance to make his work more authentic, more moving.

“I had brought just one copy of that play to Haifa,” Mark said. “I wanted to take a break from it, to pray about it. I was stuck, and I didn’t know what to do with it. Then I met Azadeh.”

He handed her the play, they exchanged email addresses and phone numbers and then said their goodbyes.

MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA, January 2001 — Azadeh always wanted to help people, so she entered nursing school and enjoyed it until she came face to face with blood and death. She had experienced enough of that. Seeking something less intense, she chose to become a dental assistant. When she wasn’t at her job, she was working with youth in her community — organizing gatherings based on service activities that stressed virtuous living and standing up for justice.

Azadeh had no plans to leave her family or Australia, but as she and Mark emailed and talked on the phone, it became clear that they were meant to be together. During their first meeting since Haifa — when Mark was on winter break — he and Azadeh were married.

CHAPEL HILL, August 2002 — When Azadeh was hired as a dental assistant at UNC, she took it as a sign that Chapel Hill was the place for her. Meanwhile, Mark worked on his play and, with insights from Azadeh, pursued a staged production in Durham.

“She knew the background and the people,” Mark said. “She told me how things would be done and said in Iranian culture. She was so close to the story of Mona, and that helped the actors create a close spiritual and emotional connection to the story.”

Mark formed a theater company, The Drama Circle; A Dress for Mona was the company’s first play and received good reviews in the Triangle. It also laid the groundwork for his second Baha’i-inspired Drama Circle performance, On the Rooftop with Bill Sears.

The two plays helped Mark earn a position as a lecturer in dramatic art at UNC, where he would return A Dress for Mona to the stage and where he and Azadeh would work with the UNC Baha’i Club on a youth outreach program. The goal: to foster the spirit of service in young people who were not welcome in their own country.

‘I don’t believe in taking opportunities in one country and then leaving that country. We want to do good things to help this country and the people who live here. They saw us for whom we are — nothing more than good students with potential. Now we want to give back.’

Sepehr

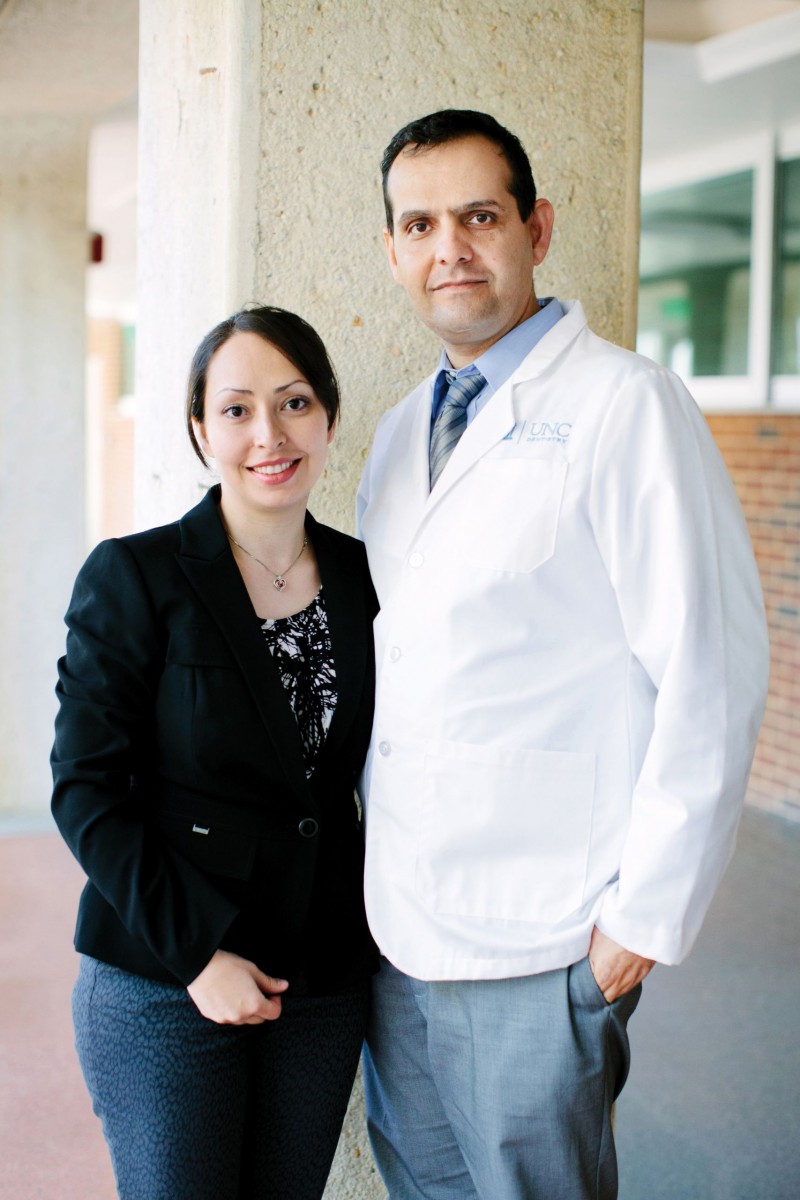

Shabnam Ranjbar and Sepehr Kaiser didn’t want to leave Iran but, as Sepehr said: “At some point, you feel disabled. They take your life.” He practices dentistry in Greensboro; she teaches aspiring dental students. (Photo by Anna Routh Barzin ’07)

CARRBORO, September 2007 — After taking courses at Alamance Community College and Durham Tech, Shabnam and Sepehr applied to UNC. Their transcripts were full of top marks and looked like typical student-transfer applications. What the staff at UNC admissions didn’t know was that Sepehr and Shabnam had taken three years’ worth of college-level courses in Iran as part of the Baha’i Institute for Higher Education, an underground university taught by Baha’i academics inside Iran and around the world. Mark Perry, for instance, taught Shakespeare via Skype to Iranian Baha’is.

Learning in homes and nondescript buildings might seem safe enough, but when government officials found out about gatherings, they broke them up and confiscated computers, books and course materials. Instances of such events were presented in 2011 in a documentary, Education Under Fire, which was co-sponsored by Amnesty International. Also that year, there was a systematic and widespread raid of BIHE homes and places of study. Students and teachers were jailed, spawning the “Education Is Not a Crime” campaign championed by Maziar Bahari, an Iranian journalist who was jailed for his work covering Iran’s Green Revolution in 2009. Bahari’s memoir of his experience is titled Then They Came for Me: A Family’s Story of Love, Captivity, and Survival.

In the U.S., Shabnam and Sepehr didn’t bother trying to get credit for their BIHE work. “We knew we had to reestablish our academic track records,” Sepehr said.

At UNC, they both studied biology with their eyes set on dental school. Both pursued undergraduate research, and Shabnam impressed her mentor, Sylvia Frazier-Bowers ’99 (PhD), so much that she and Al Guckes, assistant dean for admissions, urged Shabnam to apply to dental school before receiving her bachelor’s degree from Carolina. Though rare, this isn’t unheard of.

Sepehr joined her at the dental school the next year, and the two set out to fulfill a new dream — to open their own dental practice as a husband-and-wife team, an impossible reality for Baha’is in Iran.

“To me, North Carolina is home,” said Shabnam, now a mother of three. “I was never welcome in my birth country, and UNC welcomed us. This great university gave us the opportunity to work hard and succeed, to be part of a community.”

Even if things change in Iran, it’s doubtful the family would move back.

“I don’t believe in taking opportunities in one country and then leaving that country,” said Sepehr, who now works as a dentist in Greensboro. “We want to do good things to help this country and the people who live here. They saw us for whom we are — nothing more than good students with potential. Now we want to give back.”

They live in Mebane, in a subdivision full of new homes. Former UNC basketball star David Noel ’06 lives nearby. None of the neighbors cares too much that they’re dentists doing well. No one sees a conspiracy in the academic books on their shelves. The Kaisers — the name Americanized from Gheisar — are simply Americans and Baha’is, two people who will never take their education for granted.

TEHRAN, MAY 2008 — Seven men and women identified as leaders of the Baha’i faith in Iran were arrested for “spreading corruption on Earth” and “spying for Israel.” One of the men was Azadeh‘s brother-in-law, Saeid Rezaie.

At the trial, no evidence was presented; their counsel, Shirin Ebadi, a Nobel Prize-winning human rights lawyer, was unable to consult with her Baha’i clients. Then the seven were found guilty. They could have been sentenced to death, but an international outcry, including voices from human rights organizations and the U.S. Congress, was intense. Eventually, the seven were sentenced to 20 years in prison.

When American journalist Roxana Saberi was jailed in Iran and eventually released, she spoke of the strength of Baha’i prisoners, calling them some of the strongest souls she had ever encountered.

“When I went on a hunger strike, [Baha’i women] Mahvash and Fariba washed my clothes by hand after I lost my energy, and they told me stories to keep my mind off my stomach,” Saberi wrote in The Washington Post. “Their kindness and love gave me sustenance. It pained me to leave them behind when I was freed. I later heard that Mahvash, Fariba and their colleagues refused to make false confessions, as many political prisoners in Iran are pressured to do.

“I know that despite what they have been through and what lies ahead, these women feel no hatred in their hearts. When I struggled not to despise my interrogators and the judge, Mahvash and Fariba told me they did not hate anyone, not even their captors. ‘We believe in love and compassion for humanity,’ they said, ‘even for those who wrong us.’ ”

A year before the seven were jailed, three of Azadeh’s nieces were arrested with a group of other high school students, including Muslims. They had been teaching math, science and other typical school subjects to the poor of Shiraz. The Muslim students were released immediately. Azadeh’s nieces and other Baha’is were kept in jail for seven days.

‘I love the opportunity UNC gave me. I love the people here, who support what Mark and I are doing in the community. But it breaks my heart to know that there are people in Iran — Muslims, Baha’is, Christians, Jews and others — who just want to help their people and help society progress. But Baha’is aren’t allowed. Because, really, things have gotten so bad in Iran that just to be a Baha’i is now a crime.’

Azadeh

When Azadeh was hired as a dental assistant at UNC, she took it as a sign that Chapel Hill was the place for her. (Photo by Anna Routh Barzin ’07)

CHAPEL HILL, May 2015 — It’s a Friday night, and Azadeh and Mark are spending their free time doing what they’ve been doing for 13 years — working with youth. Most of them are from Myanmar, formerly Burma. The kids are part of the Karen ethnic minority — pronounced kuh-REN — and they fled persecution in their country.

The goal of this work is simple and nondenominational — to help youth ages 11 to 14 develop skills to keep materialism and selfishness at bay while becoming agents of service to others. The UNC Baha’i Club came up with the idea to reach out to the wider community, and Mark and Azadeh have sustained the efforts with the Karen kids.

“The kids come up with ideas to serve their community,” Mark said. “We just help them focus on one idea, consult about it, commit to it, follow through with it and then reflect on the entire process. The project could be cleaning up trash in their community or building a garden. Whatever it is, we want to help them practice a model of service so that service doesn’t get trapped in the realm of idea.”

Through this process, kids have built friendships, learned about environmental stewardship and the meaning of service, and developed the capacity to complete a project together. “The goal is to make service part of who they are,” Azadeh said.

Mark and Azadeh have led what they call “junior youth groups” from 1 to 6 p.m. every Saturday for more than a decade. In the Triangle Baha’i community, there are dozens of such groups.

In 2014, Mark and Azadeh switched gears to work with some of the participants who had aged out of the program and wanted to become mentors like them and lead service projects with younger kids.

“The population of kids we work with is susceptible to some serious social problems,” Mark said. “But we don’t focus on that; we see in them incredible potential and the possibility of becoming servants of humanity, not just consumers or not people who are crushed by the despair of a society that doesn’t care about them.”

If one were to label Mark and Azadeh as do-gooders, they would push back: “We don’t tell these kids what to do,” Mark said. “The service projects are based on their ideas. We don’t even consider this outreach — these kids are extended family. They text us. They message us on Facebook for a little help with homework. They’re family.”

Azadeh added, “They even call us mom and dad.”

Meanwhile, in Iran, this sort of work is similar in spirit to that of Azadeh’s nieces, who were arrested when authorities suspected that Baha’is were corrupting other youth.

“I try to live by what my dad told me, to live my life wherever I am,” Azadeh said, “and I simply love to work with kids. I always have. So I’m happy to be part of this community. I love the opportunity UNC gave me. I love the people here, who support what Mark and I are doing in the community. But it breaks my heart to know that there are people in Iran — Muslims, Baha’is, Christians, Jews and others — who just want to help their people and help society progress. But Baha’is aren’t allowed. Because, really, things have gotten so bad in Iran that just to be a Baha’i is now a crime.”

Mark added: “But we know that the radicals in charge of Iran won’t win. They’ve been trying to snuff out the Baha’i faith since the 1850s, when tens of thousands of early believers were slaughtered. But they haven’t succeeded. History is on the side of the Baha’is suffering in Iran. And the world is watching.”

Mark Derewicz is a freelance writer and the communications manager for UNC’s School of Medicine. His articles for the Review include the story of a special legacy to the North Carolina Cancer Hospital, “She Taught Us What Loud Means,” in the November/December 2015 issue.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.