Why Not? The Art of Believing

Posted on May 2, 2019

Katie Ziglar ’79 boils the secret of her success down to a single, familiar question: Why not?. (Anagram photo/Graham Terhune)

Katie Ziglar ’79 has always chased what lay beyond life’s boundaries. She hopes to redefine them for the Ackland.

by Beth McNichol ’95

Piles of snow from an unexpected winter storm still hug light poles and bus shelters outside the Ackland Art Museum as Katie Ziglar ’79 comes in from the December cold. She parks her coat on a hook in the Ackland’s modest upstairs office suite and points to the stocking.

Ziglar doesn’t have a scoreboard in her office that tracks how many times she’s proven the naysayers of the world wrong — just a sparkling pink Christmas stocking hanging from her doorknob.

Someone has told her the stocking is absurd. She has decided it’s cool, and when Ziglar believes in the power of an idea or a project or even two pieces of velvety fabric stitched together, it persists — across the decades, across continents, through the halls of the Smithsonian, in the mansions of maharajas, over the demolition of gender barriers and through her polite-but-persistent, lifelong takedown of the phrase, “That can’t be done.”

That’s why she’s here: to take a certain building hanging around the front porch of Carolina’s campus and turn it into a priceless thing. A cool thing. A proud thing. The Ackland Art Museum turned 60 last September, and no amount of calisthenics can minimize the structure’s years. It’s been the cramped home to some of the most significant works of art held in North Carolina for at least two decades, and unlike that pink stocking, the museum’s squatty, aggressively brick façade is about as inviting as the tomb inside that holds Ackland’s eponymous benefactor.

The “absurd” Christmas stocking hints at her determination. (Anagram photo/Graham Terhune)

As an architectural feat … it’s OK. As a building that Ziglar wants to one day house the nation’s preeminent public university art museum? Some windows would be nice.

And exhibition space. And education space. And storage space. And office space. And a cafe.

Ziglar walks over to a color rendering tacked to the wall of the last time the Ackland came close to getting new square footage — a 2005 expansion that was well into the planning stages when the then-director pulled it. This failed plan would have been an improvement, but it wasn’t a new building. And for Ziglar, who has built a career out of making others believe in the power of art’s reach, nothing else will do. She has a fan club that stretches from here to Japan, and you know when Katie Ziglar isn’t messing around.

She looks at you with a pursed smile on her lips and the kindest glint of steel in her eyes. “This,” she says, pointing to the erstwhile sketch and all that it represents, “is the reason that I came back.”

Why not?

When you’re a member of the first class of women to win a Morehead Scholarship at UNC and the first member of your family in five generations to leave your small town for good, you know a little something about boundaries — those that hold back power, and those that hold back time.

Then there was Cynthia. Cynthia from when Katie was 6 years old — a dental school classmate of her father’s in the early 1960s. No one else in his class looked like Cynthia or sounded like Cynthia; she seemed to Katie to exist in a rarified universe, a kind of superhero.

“I knew all about her,” she said, “just because she was the only woman.”

If you were Ziglar, in other words, you had a sense of the possible before you were told you shouldn’t. You believed.

Her family returned to Rural Hall, a then-unincorporated town of 1,000 just north of Winston-Salem, after Dr. James Ziglar ’63 (DDS) earned his degree. There, he ran a private practice while Katie’s mother, Barbara, a junior college graduate, raised Katie and her three siblings on the Ziglars’ small farm.

Their daughter started breaking through barriers in fall 1973. The administrators at Chapel Hill High nominated a woman for the Morehead Scholarship, a senior named Ann Hollander — the first woman ever put forth for the award. Why not? they asked.

The shift to art

The chairman of the Morehead trustees at the time provided an answer as notable for its word choice as for its content.

“A woman is not likely to achieve success in later life in business and politics,” Hugh Chatham told Bunky Flagler ’74, a female reporter for The Daily Tar Heel.“They are more than likely going to be housewives. If I could get an honest-Injun pledge written in blood that a girl would not get married and have children, but be a politician or a leader, then we’ll have women in the program.”

Public pressure, bad publicity and the threat of a lawsuit from the National Organization for Women turned out to be as convincing as a blood pledge. The next summer, the Morehead invited women to compete. Ann Hollander had gone to Stanford by then, but into the breach went Katie Ziglar and 11 other women, who picked up that “Why not?” and ran with it. They entered their own rarified universe at Carolina in 1975 — they called themselves the Dirty Dozen.

“The worst thing that can happen is you’ll be told no.”

— Katie Ziglar ’79

Many Moreheads in her class chased law or business, just as Chatham expected. Ziglar thought she might, too, until an Islamic art course during her final semester got her thinking about the ways in which we see our differences before our similarities.

The class was “revelatory.” It sparked in her the realization that Americans didn’t understand a part of the world that was growing in importance, a region dominated by a monotheistic religion — not unlike the United States.

Then as now, Ziglar was studious and deliberate; she wanted to make an informed choice about her future after UNC — in New York, where she could try on art or law and see what fit.

After Ziglar found that she couldn’t live on the salary from her first job in Manhattan, in historic preservation, she joined the powerhouse law firm Skadden, Arps as the dedicated paralegal for their rainmaker, Robert Pirie. When Ziglar wasn’t back and forth across the Atlantic with the firm, she was delivering casework to Pirie at his farm in Massachusetts, where he had amassed a renowned collection of paintings and rare books worth more than $15 million.

Pirie, who died in 2015, was a bullish lawyer who helped build Skadden into one of the most profitable firms in the world. But it was through their shared love for art that he and Ziglar built a lifelong friendship. She was developing what would become a guiding philosophy in her career, that “the human experience in all of its range is reflected in art.”

Ziglar was still considering law school. But Pirie encouraged her to do what she wanted to do all along, the thing that no one would expect a young woman from Rural Hall to do.

A sudden letdown

A ninth-floor apartment with sketchy electricity and cold morning treks through muddy streets to the “craziest, crowded” places to study madrassas and mosques — this was Ziglar’s life at the American University in Cairo in 1982, and to her it was glorious.

“I just lucked into this incredible scene.” She studied in Cairo alongside futureNew York Times columnist Nicholas Kristoff, among other luminaries. “These were just the coolest people around. No one knew what they were going to become in the future, but they were smart, and it was extraordinary.”

In Egypt, Ziglar “worked my fingers to the bone” to earn a master’s degree, straight A’s all the way, and committed to a career in Islamic art history. But just as she prepared to enter the one doctoral program from which all jobs in the field flowed, its director, Harvard’s revered Oleg Grabar, retired.

“I was devastated is an understatement for how I felt.” Few teaching jobs and even fewer museum positions existed in Islamic art as it was, and without the Grabar pipeline working for her, continuing her studies elsewhere was a risk she felt she couldn’t take.

What fit better, she wondered – art or law? Her heart was with the former, and she pursued the tiny niche of Islamic art straight into a dead end, then pushed on through. (Anagram photo/Graham Terhune)

“I knew many people who took far more than five years to get Ph.D.s. I was intimidated to say the least, and I was really afraid to launch into a program where I didn’t feel my future was more set.”

The same traits that helped make her an excellent student — an analytical mind and penchant for preparedness — sometimes acted as a brake for Ziglar when faced with the start of a new venture, said her husband, Dick Miller. A Princeton graduate and Fulbright Scholar who earned a master’s degree at the American University in Beirut, Miller likes to say that they both “ran away from their villages” — he from a farm in Connecticut, she from one in North Carolina. But Miller had wanderlust in his DNA, he said, while Ziglar had to learn to trust hers.

“When you’re brought up to be restrained, you occasionally get a little fearful stepping out where you shouldn’t be fearful,” said Miller, who met Ziglar in Washington, D.C., where she had reset following the Grabar disappointment. “She didn’t have to struggle with me about that. I could support her and give her encouragement.”

Miller gave up his peripatetic existence as a globe-trotting consultant in 1990 to make a life with Ziglar in Washington, where he built a successful financial planning practice and an even more successful marriage. Choosing between Ziglar and that wanderlust of his wasn’t even close, Miller said.

“Katie was everything.”

Why not?

“Newly married and really happy,” she found her way into public relations, marketing and development at multiple Smithsonian art institutions at a time when they were just starting to see their government funding decrease. There, she discovered a new-but-familiar skill: Like her one-time mentor, Katie Ziglar became a rainmaker.

She convinced the Principal Financial Group in Des Moines to help fund eight simultaneously traveling exhibitions that crisscrossed the country while the Smithsonian American Art Museum was boarded up for a three-year renovation. It was the museum’s first multimillion-dollar sponsorship, an accomplishment that blew then-director Betsy Broun’s mind.

“It was just funding on a level that I had never dreamed of, that kept us visible in the landscape when we were otherwise closed,” Broun said.

Later, as the director of external affairs at the Freer|Sackler, the Smithsonian’s galleries focused on Asian art from Istanbul to Tokyo, Ziglar tripled the museum’s annual fundraising and in 2008 launched a successful endowment campaign during a troubled economy. Like a detective seeking informants, she traveled the world in search of “maharajas, lords and ladies, people of tremendous wealth and with great collections” who could loan their works to the Freer or support an exhibit showcasing their culture in the U.S. capital.

She convinced Portugal’s competing banks to share in the sponsorship of a huge exhibit that highlighted that country’s 17th-century empire, raising more than $6 million. It was a rare collaboration in an industry that isn’t known for it, and her success “flabbergasted” development circles in Washington, D.C., she said. She had broken the mores of marketing.

But Ziglar understood what others could not see: That Portuguese heritage, and the melancholy of lost power that haunted it, was stronger than corporate identity — that the human experience in all its range is reflected in art.

“This was an extraordinary dance,” said then-Freer director Julian Raby, who sometimes clashed with Ziglar over how far to chase funding — with Ziglar often proving him wrong. “These relationships are not just a transactional thing for her.”

Colleagues told stories of going to Ziglar to politely pillage her secrets, which she boiled down to a single, familiar question: Why not?

It was equal parts naiveté and belief, “just really being inspired by the concept enough myself that I could go and talk to people about being a part of it,” Ziglar said. “There’s also the satisfaction of knowing that you’ve made something possible — something really important possible. The worst thing that can happen is you’ll be told no.”

The little bit of electricity

The thing about Ziglar, though, is that after the first no, she’ll keep calling. Researching your interests. Inviting you to coffee. Figuring out what matters to you. Asking what she could have done differently — always politely. Until one day, you don’t just give in to her resilience. You believe in her cause.

“Katie is a ferocious asker,” said Miller, who called her persistence “the little bit of electricity” that makes things happen.

Ziglar has brought that electricity to the Ackland, returning in 2016 as director of the place where, as a Carolina senior, she was an intern. Museums traditionally have drawn from scholarly and curatorial ranks when hiring leadership; Ziglar, who trained at the Getty Leadership Institute for Museum Management in 2015, initially figured she was a long shot for the Ackland position. It was the first directorship she’d applied for.

But former Freer|Sackler colleague George Rogers never doubted Ziglar was headed back to Chapel Hill.

“Museum directors now, let’s face it, have to be fundraisers,” he said. “But the chances of finding someone who’s an excellent fundraiser who also has her academic chops — to have an advanced degree in art history … and to be an alum? I mean, come on. Of course it was going to be Katie.”

“She’s in the vanguard of what’s needed in a 21st-century museum director,” said Lee Glazer, director of the Lunder Institute for American Art at Colby College and a past curator at the Freer. “Museums are becoming gathering spots that serve the community in ways that go beyond aesthetic appreciation or research.”

Underperforming

On any given day, the Ackland might host a group of first-year dental students studying art to deepen their understanding of three-dimensional space. Math students thinking about abstraction. Alzheimer’s patients exploring their emotions through one-on-one, docent-led tours — a two-year-old program in rising demand. There are school groups, casual visitors and art aficionados.

But the Ackland is underperforming in reach, Ziglar said, and its cramped quarters are the reason. Despite a superior permanent collection of drawings, prints and photographs, the only Asian art collection in the state and free admission, it draws half the annual attendance of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke. (Ackland’s yearly visitors have increased from 40,000 to more than 50,000 since Ziglar’s arrival.)

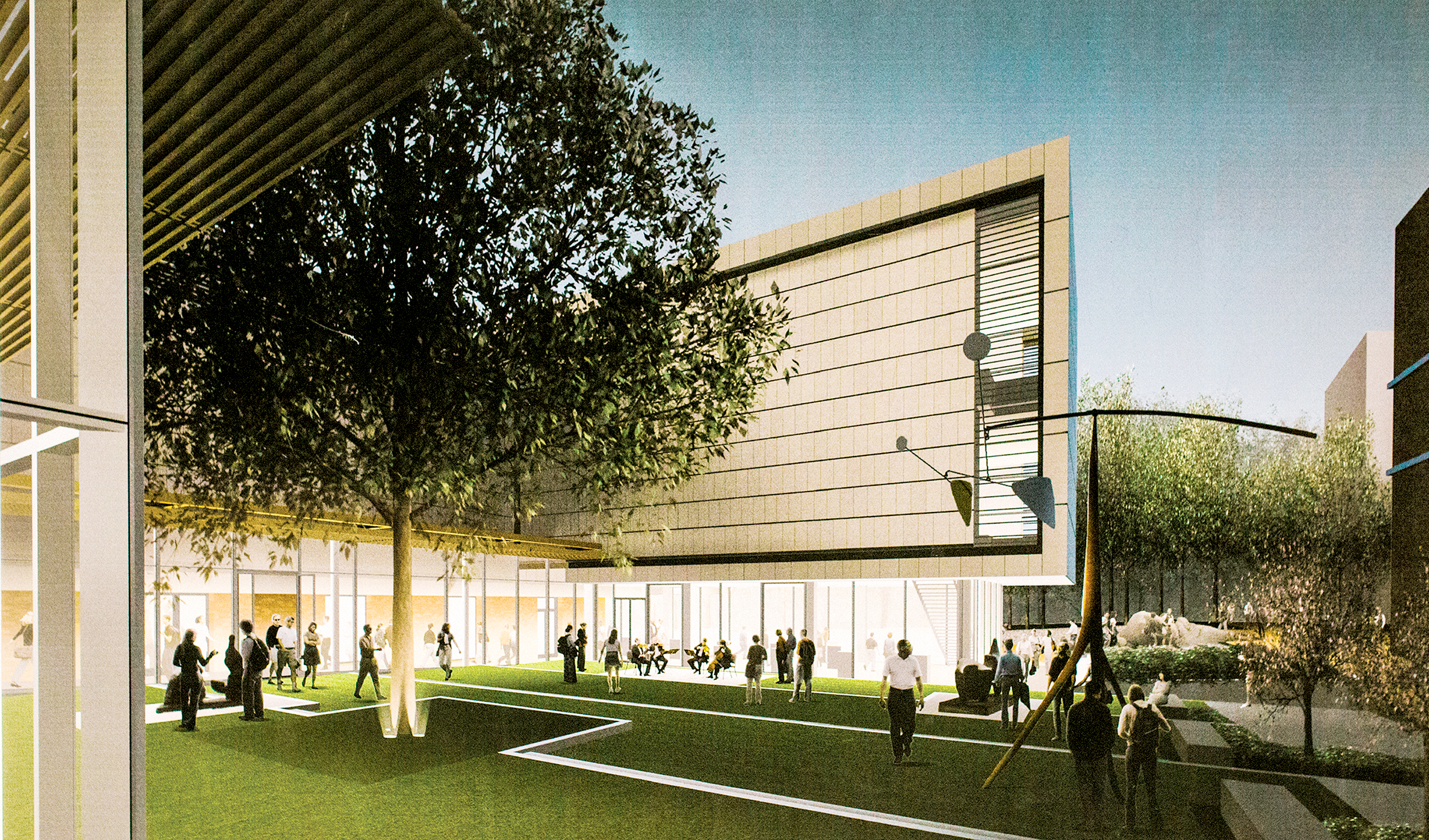

This 2005 reimagining of the Ackland was shelved. Ziglar intends for the next one to become reality.

Soon after the Nasher’s opening in 2005 — in airy new construction with plenty of space for special exhibitions — the Ackland scrapped its expansion plans, causing painful reverberations to ripple across the institution’s financial support and participation levels.

The University had touted the expected donation of more than 100 mid- to late-20th-century works from the private collection of Ackland board member Jim Patton ’48 and his wife, Mary, as far back as 1999. But in 2008, the Pattons, citing the Ackland’s space issues, had a change of heart. They gave their significant trove to the N.C. Museum of Art in Raleigh instead.

Missed opportunities chafe at Ziglar, who has access to the kind of rocket fuel that can raise attendance and boost the museum’s prominence. Last summer, the Ackland was the only public university art museum in the country and the only institution in the Southeast to host The Outwin, a Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery exhibit that included work by Michelle Obama’s portraitist, Amy Sherald.

“They have us doing this [renovations] some years out. But we’re 20 years overdue, and we can’t just limp along indefinitely.”

— Katie Ziglar

While the exhibit was at the Ackland, Sherald gave an inspiring talk in front of a packed crowd of women and their young daughters … in an auditorium on the other end of campus.

“We had a celebrity of sorts and a real chance to offer something very special,” Ziglar said, “and no place in the museum to do it.”

Ziglar has plans, already chugging along, that will produce sketches of what a new Ackland could look like — same location, twice the square footage — within a year or so, in time to ride the tail end of the University’s $4.25 billion capital campaign and build donor support for new construction.

The Peck effect will help. The $17 million collection of Northern European works — including the only collection of Rembrandt drawings held by a public university museum — that Dr. Sheldon Peck ’63 (’66 DDS) and his wife, Leena, gave to the Ackland in 2017 already has had a huge impact. The gift, which included an additional $8 million to fund a curator and traveling exhibit, made the Ackland “a powerhouse for Northern European drawings, in one fell swoop,” and it has created a domino effect of alumni giving, Ziglar said.

But while a new home for Ackland is mentioned on the Campaign for Carolina website, the University master plan doesn’t commit to a new building instead of renovations and, according to Ziglar, doesn’t seem to be in a rush either way.

“They have us doing this some years out. But we’re 20 years overdue, and we can’t just limp along indefinitely.”

Betsy Broun, who led the Smithsonian American collection for 27 years, said she has cautioned Ziglar that her biggest challenge probably won’t be outside funding. It’ll be quixotic institutional dynamics.

“People come, people go,” Broun said a few days before Carol L. Folt submitted her resignation as UNC’s chancellor. “What you hope is that your administrators on campus see the necessity of finishing what you start.”

For her part, Ziglar said she would miss Folt’s “unstinting support” of the museum, where the chancellor chose to have her farewell reception in January. But she said she was “confident the next chancellor will share our exciting vision for the future, which includes a new building for the Ackland.”

Why not? Betting against Ziglar, after all, doesn’t seem wise. Miller once presented her with a gift for her office wall, a kind of abstract portrait of Ziglar the Naysayer Slayer. On one side of the frame was a letter from the Principal Financial Group, informing her that the company would not sponsor the SAAM’s 1999 exhibition.

On the other side? A copy of a hefty check from Principal that arrived one month later.

Beth McNichol ’95, a freelance writer based in Raleigh, is a former associate editor for the Review.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.