Not Done, By a Long Shot

Posted on May 2, 2019

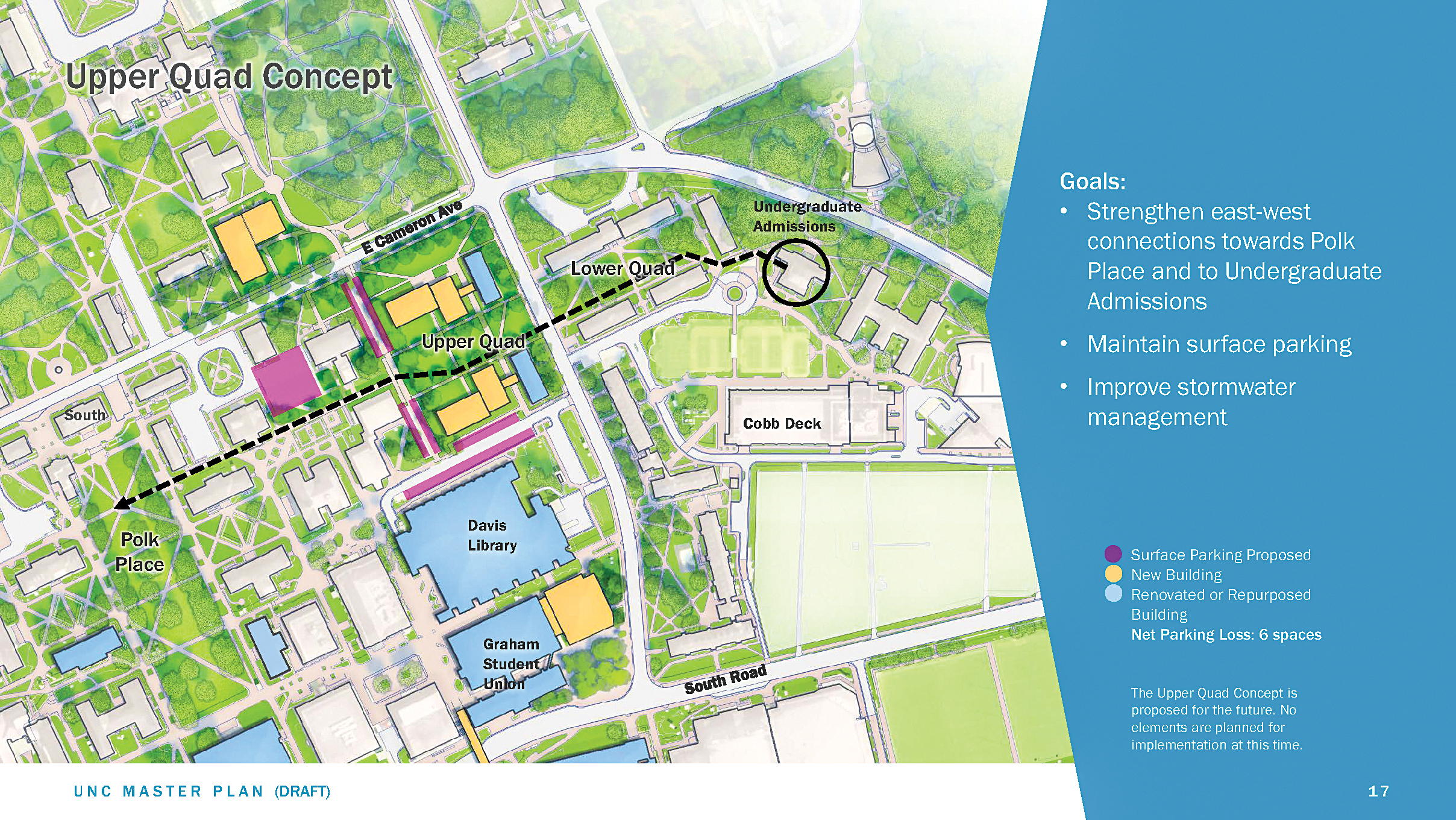

The dotted line on the map represents a plan for fairly simple first-impression improvements on a visitor’s walk (prospective students and their parents) from the admissions office to scenic Polk Place. At right is the site of the proposed Institute for Convergent Science among newer physical sciences buildings to the west of the oldest quads.

In a new master plan for the campus, Carolina looks to keep its research enterprise in one place, plots a new science project and prepares to take down residence halls for the first time.

by David E. Brown ’75

“I think the sense is that this is it. This is enough.”

It was 2006, and it seemed like anywhere you wanted to go on the campus involved a detour around cranes and construction fences, when one of Carolina’s architects uttered those words. Easily said in those days. To be real, the only practical approach to the modern research university is constant change.

Make no mistake: There will be no repeat of the 50 percent growth in built square footage that occurred in a 10-year period. But the physical plant remains a work in progress.

The trustees could vote on whether to approve a new master plan for the campus in May. Like the one UNC began to execute just before the turn of the century, some of it is just ideas that would take many years to accomplish — and others that will change or vanish — with the direction of higher education, the march of technology and the availability of money. These three have some legs:

■ Carolina, which has repurposed residence halls but never has torn any down, will begin to. Parker and Teague, late-1950s suite-style dorms, likely will be first. That doesn’t bode particularly well for hallway system dorms, which are no longer to students’ liking and are not easy to remodel. Funding to replace them isn’t the issue it is with classroom and administrative buildings — residence halls can be built by borrowing against room rent. Areas #1A, #1B, #1C on map.

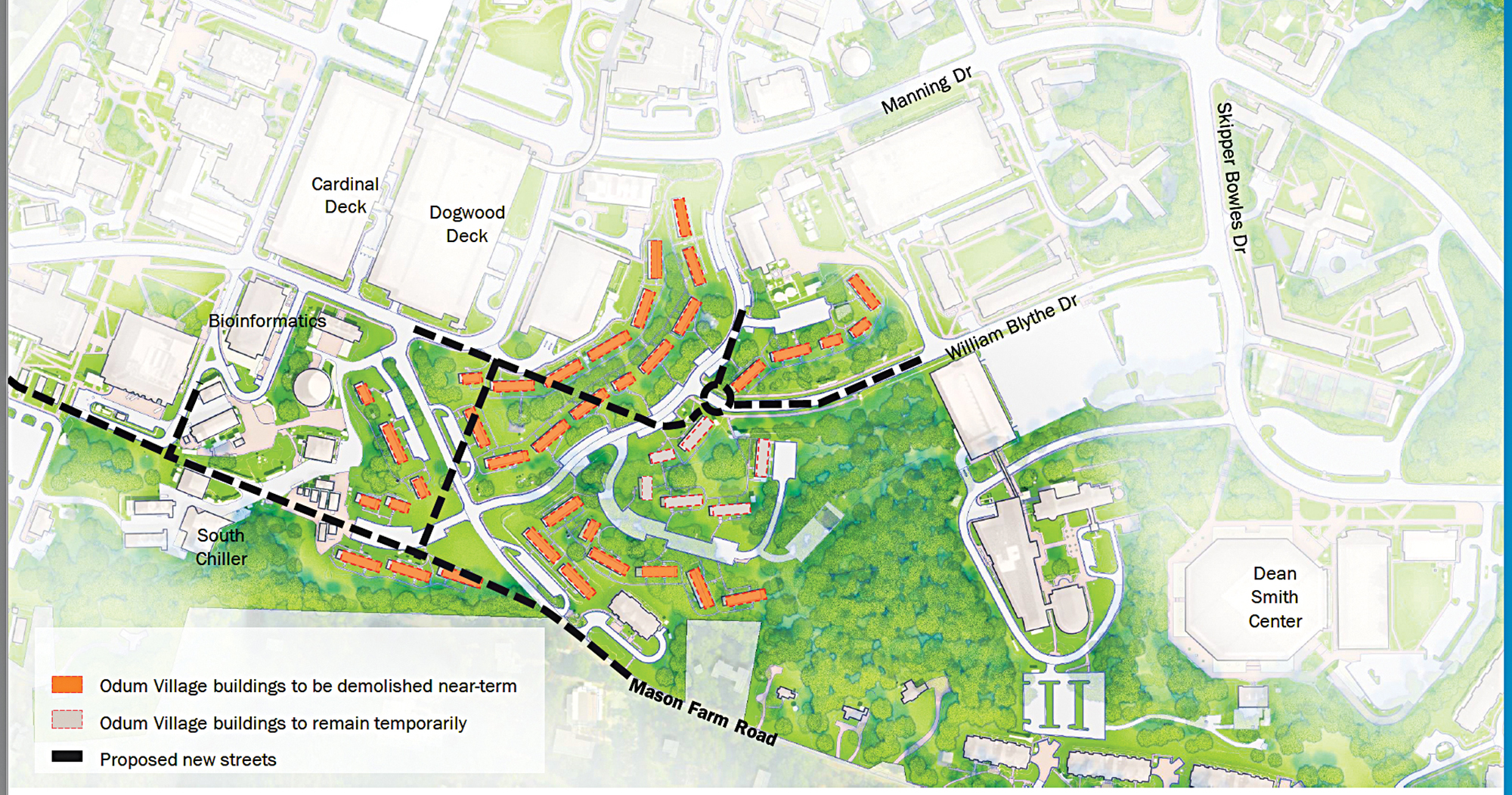

■ Research endeavors are not looking to the north. There’s been a change of heart about the plan that emerged in the first decade of this century to target parts of the 1,000-acre Carolina North site for future research facilities. Scientists do not want to travel back and forth between their labs on South Campus and a satellite more than a mile away. New research facilities likely will be developed to the east and south of existing buildings, and there will be lots of room as units are razed in what many alumni remember as the Odum Village apartments. Area #2 on map.

■ The area now bordered by the 1970s chemistry lab high-rises and the relatively new physical science buildings — built in the early 2000s boom at a cost of some $200 million to address a critical need for modern science space — was envisioned as an open quad. Now that’s more likely to be the home of a very large building to address what’s known as convergent science, where different scientific disciplines are brought together to solve specific problems as opposed to the traditional approach of working on solutions in their separate quarters. Area #3 on map.

Any master plan is as notable for difficult questions as for concrete direction:

■ Continued growth of research facilities and infill on the older parts of the campus raise again the perpetual question of how nimbly we can move into and out of an increasingly densely populated campus and from place to place within its borders. Planners had hoped that a light rail line along the southern border of the campus, connected to Durham and beyond, would be one solution. That plan died in March after Duke University declined to cooperate. They also envision making parts of North Campus more inviting to visiting pedestrians and razing some buildings on South Campus to make the old Medical Drive — the original entrance to Memorial Hospital off Columbia Street — a through street to the east side of the hospital complex.

■ Where will the money for classroom and administrative buildings, roadways and infrastructure upgrades come from? There is no bond issue windfall as there was in 2000, and state funding for capital projects has shrunk. Planners acknowledge the need for private money to play a larger role this time — both gifts and business partnerships. But master plans essentially are wish lists and expressions of need, to be in place as the money questions are addressed.

Teague and Parker dorms, opened in 1958, were designed in the suite style – three to five rooms to a bathroom – now out of favor with students who want fewer rooms to a bath and more common space. (Photo by Jeffrey A. Camarati)

Dinosaur dorms

Not everybody loved every dorm experience, but you seldom find anything on the campus closer to the alumni heart than the places they called home. Allan Blattner explains why some of them will have to go.

“A lot of our stock is double rooms, go down the hall to the community-style bathroom which is a row of showers and a row of commodes, and that only gets you so far,” the director of housing and residential education said. “And those buildings, as much as we’ve tried with what’s called a medium-scale renovation to turn those into suites, well, you lose bed capacity.”

For example, in the upper and lower quads, “these really quaint little 90-person buildings” suddenly become 50-person buildings when you turn some rooms into the highly demanded singles and convert others to common space. “The rent that I would have to charge to recoup the cost of that renovation would price us out of the market.

“The feedback we hear from students is single-bedroom, single-bathroom living facility and ability to cook for myself. Well, that screams apartment. We can’t [renovate] everything to an apartment — they couldn’t afford it, we couldn’t build it fast enough.”

Parker and Teague could serve as a parable for the direction housing is going.

They house 340 students on three floors and are not hallway-system dorms — they have three to five rooms to a bathroom in a suite arrangement. But Blattner now refers to this as “short corridor.” The future of the suite style is no more than three rooms to a bathroom, with a common room.

To accommodate a more palatable arrangement and increase density at the geographical center of the campus, Parker and Teague would have to be taller. Built in 1958, they are younger than the Carolina dorm average age of 74. But they sit alongside the six-floor Carmichael and back up to athletics fields; unlike North Campus, new six-floor dorms on the Parker and Teague footprint are considered aesthetically acceptable.

“Parker and Teague need comprehensive renovations. It doesn’t make sense to renovate Parker and Teague as is because it’s a housing type that is not as attractive,” said Anna Wu, associate vice chancellor who oversees planning and building. “And we could get more density in there,” 500 to 600 beds. “And it’s right in the middle of campus.”

Other older dorms are being talked about — a planning map shows Ruffin and Grimes in the upper quad missing, replaced perhaps by administrative or academic space; on a more long-term map, Craige, one of the smaller South Campus high-rises, is replaced, maybe with a new residence hall, maybe with an academic building.

Ruffin and Grimes and the other two upper quad residence halls, Manly and Mangum, each house fewer than 100 students. And start subtracting rooms when you add elevators and common space and make the restrooms accessible.

Aerial view of the site of the proposed Institute for Convergent Science among newer physical sciences buildings to the west of the oldest quads. (Photo by Jeffrey A. Camarati)

Convergence

It was the last frontier on what’s now known as the northern half of the campus, just woods except for old Venable Hall and the Naval Armory.

Tall chemistry lab towers sprang up in the 1970s; then more recently, a computer science building, and another building for physics, astronomy and marine science, and a new Venable and other chemistry space. Note that each one of these caters to a specific science discipline. That’s what is starting to change in the sciences, and the open space amid these buildings — once envisioned as a grassy quad — is the target for a place where the sciences would converge.

The Institute for Convergent Science would be the largest academic building on the campus except for the two big libraries. At 317,000 square feet, it would consume all that open space plus the armory.

In simplest terms, convergent science starts with the problem, then goes out and gets the expertise to solve it.

Say you’re researching water purification. “Let’s bring together the team early that’s going to innovate on this question, and let’s don’t respect disciplinary boundaries, so if we need an environmental scientist, a chemist and a physicist, we’ll put those folks together on a team,” said Chris Clemens, senior associate dean in the College of Arts and Sciences and a physics and astronomy professor. “But more than that, if we need an expert who understands the criteria for measuring drinking water, to say it has met specifications for regulatory approval — why don’t we have them influence the decision-making process from the first day?”

“So, a space that doesn’t belong to a department, doesn’t belong to a principal investigator, doesn’t belong to individual faculty but is shared and programmed to create the collisions that you need for people to come up with ideas.”

–Chris Clemens, senior associate dean in the College of Arts and Sciences

This has implications for the direction of the undergraduate curriculum. Courses could be created that, as Clemens said, are “taught by three professors across three disciplines on a single topic but coming at it from the perspective of three different subject areas.”

A different building, too.

“It looks very different than the buildings we have so far. We want at least half the building to be dedicated to flexible space and interaction space. So if you can imagine coming in on a ground floor that’s very open, long sightlines, with makerspaces where students are making prototypes of ideas they have or working on class projects, with meeting rooms where you have a programmed activity to bring scientists and technologists and business people together to talk about the key problems they want to work on.

“So, a space that doesn’t belong to a department, doesn’t belong to a principal investigator, doesn’t belong to individual faculty but is shared and programmed to create the collisions that you need for people to come up with ideas.”

The institute is an example of what planners call “hubs” — considered key to the future of the research university. They’re sort of the opposite of the traditional academic layout in which different disciplines all have separate quarters. “Intersections for people and disciplines,” Wu said. “Let’s not have siloed physical facilities.”

Other examples include makerspaces — collaborative work spaces being opened across the campus where students learn creative use of tools, from 3D printers to sewing machines; and libraries, which are evolving from book repositories to interactive research space.

The master plan shows new research buildings scattered on the Odum site and along the southeastern corner of UNC-owned land — as well as a logical site for a park-like open space.

Turning back to the south

The trustees in 2005 approved the first two building sites on the satellite campus that Professor Horace Williams gave the University after he was through raising cows there: an 80,000-square-foot research incubator building and a school to be run by the Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute.

When the economy faltered in 2008, the private developer of the research venture went away. Now there’s a solar farm going in where until recently the airport was, and there’s talk of campus recreation fields on the portion of the 1,000-acre tract that UNC and the town have agreed can be developed. It’s still a viable and wide-open building site for a growing University.

But the research community has embraced a culture of collaboration among chemists, doctors, physicists, pharmacists, social scientists and others, who have signaled they do not want to deal with the geographical separation from the main research campus.

“Look at where all of our research cores are,” Wu said. “They’re all on South Campus. And the other thing is … the cost to enter Carolina North. That’s what we learned in 2008. How do you fund the infrastructure needed [to build a second campus]?”

“Obviously [on South Campus], we’ve got to move some roads and we’ve got to demolish some buildings, but your utilities are there.”

Demolition refers specifically to most of the 1950s-era Odum Village family student housing complex, now closed. The proximity of that land to the existing health care research complex is an easy walk. The master plan shows new research buildings scattered on the Odum site and along the southeastern corner of UNC-owned land — as well as a logical site for a park-like open space.

For many similar reasons, the School of Law has backed away from a plan to relocate at Carolina North. Wu said other professional schools in need of space are showing little interest in the satellite campus.

Get a move on

In the first decade of this century, the campus thickened with new buildings, but in practical terms, it thinned out some, too. The large student population on South Campus has a pleasant promenade to their classes across the dining and recreation complex to the east of Kenan Stadium. Extensive landscaping and new pedestrian bridges made Manning Drive, the main street of South Campus, leafier and safer. More recently, the University has created a more inviting entrance to the campus off Franklin Street at Porthole Alley and the Ackland Art Museum.

Let’s say you’ve brought your daughter to Chapel Hill to consider applying. Just now you’re a lot less impressed with where they’re putting new buildings than how it feels to stroll from the admissions office to the signature quads. It’s a straight shot on your tour, except for a parking lot and outdated landscaping that break the mood. Improving first impressions can involve some simple changes.

“We’re no longer looking at building out this campus solely by ourselves or with state money. So we’re really looking at targeted areas on campus where we will bring in partners — where it will be an interface between the campus and the public.”

–Anna Wu, associate vice chancellor who oversees planning and building

“You’re just trying to make seamless pedestrian connections,” Wu said. “A little bit more natural, a little bit more obvious. More intentional. You want the pedestrian path to be as clear as the vehicular path.”

Other movement improvement will be more complicated.

Pedestrians, cars, buses and bikes all would have it better along South Road, which bisects the campus at its center, if pedestrian bridges were built behind Student Stores and farther along the street to the west. Manning Drive has four pedestrian bridges, and UNC would like to build the other two.

Light rail would have gone a long way to easing vehicular congestion, especially on the health research campus where the station would be — the line would have skirted the southern edge of the campus.

With rail now out of the question for the foreseeable future, regional transit is an open question.

“There will be some regional transit,” Wu said. “Whatever form regional transit takes, it’s critical to campus and the community, and this plan accounts for that. This alignment could be adapted for multiple modes, and it’s important to preserve the corridor for future development.”

Who will pay this time?

In 2000, North Carolina voters approved a bond issue that brought about half a billion dollars to this campus for new construction, additions and renovations. Campus-based funds pumped up spending on bricks and mortar to about $2.3 billion.

This time around, there are no bonds and no prospects for anything on that scale. State money for construction and renovation is not what it used to be. When a trustee broached the subject of funding at a presentation of the master plan last year, the architects acknowledged they were short on answers.

The simple answer is the state funds your buildings — when it can and will.

“We’re no longer looking at building out this campus solely by ourselves or with state money,” Wu said. “So we’re really looking at targeted areas on campus where we will bring in partners — where it will be an interface between the campus and the public.”

Gordon Merklein, associate vice chancellor for the University’s real estate operations, explained a scenario that might work for something like the convergent science project: Basically, you team up with a private development company, which builds the building for you; you make a lease payment back to the developer on a ground lease; and then the University typically receives those buildings back after 30 to 40 years.

Residence halls, parking decks, dining halls and, to a lesser extent, research labs, generate revenue streams that make them easier to fund. Buildings in which researchers generate millions in federal grants receive what’s called overhead receipts — the feds reimburse the University at a negotiated rate, currently 55.5 cents on the grant dollar.

Who pays for a convergent science building that might cost $260 million?

“Business, private funding — there are donors who’ll step up to this,” Chris Clemens said. “There are donors who have made money because of Carolina’s innovations.” But, he added, “we are not going to get $250 million any other way than if the state kicks in at least half of it or maybe more.”

Jeff Hill ’92 (’02 MBA), campaign director of For All Kind: The Campaign for Carolina, agrees donors have a major part to play: “We are going to need to have private philanthropy to help us on certain projects we haven’t had to rely on before.”

“This supports the needs of the state, if you read the Commerce Department’s reports on innovation,” Clemens said. “They talk about where we lag [and] where we lead — this is going to push us from lagging to leading in certain places, I think. We’re really trying to be responsive to what we need to do for the state.”

David E. Brown ’75 is senior associate editor of the Review.

More: Excerpts from the master plan presentation to the trustees are at alumni.unc.edu/masterplan2019.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.