On the Deaths and New Lives of Campus Trees

Posted on Nov. 11, 2019

The rings of the post oak between Person Hall and New West — a tree that finally gave in last year to a spell of wet weather — dated to about 1780. “I love all my children equally,” said University Arborist Tom Bythell, “but I was really enamored with that post oak.” (Photo by Michael Everhart ’13)

Taking root around 1780, perhaps thanks to a Colonial ancestor of today’s campus squirrels, a mighty tree predated Carolina by a decade or more. For approximately 240 years, it stood sentinel, its branches climbing slowly upward as the world around it transformed.

The tree grew steadily, digging in roots as buildings rose all around and brick pathways spread in every direction. Students throughout Carolina’s history had the chance to seek shade beneath its foliage as they made their way across McCorkle Place. It grew to be the largest tree by volume on campus and eventually gained national recognition as the largest post oak in the state.

But in October 2018, after some particularly wet weather, it died.

Fungus attacked its roots — a common ailment of oak trees. In a matter of days, University Arborist Tom Bythell knew it had to come down.

The tree with which every Carolina student had the chance to interact. When the time comes for the old guys, felling and disposal typically is done as quickly as possible for safety reasons, usually followed by a short ride to Carolina North for mulching. Not so for this one. (Photo by Michael Everhart ’13)

“When you have a bad year, like a wet year, the fungus in the soil builds up. And when the conditions are just right, all of a sudden two or three oaks that seem perfectly healthy drop dead,” Bythell said. “And there’s really no way to stop it.

“I love all my children equally, but I was really enamored with that post oak,” he added.

So what becomes of something that lived before, and along with, all of us?

Knowing the history and value of the giant tree, a small team composed of Bythell, graduate student Michael Everhart ’13 and Odum Institute Director Todd BenDor worked quickly to claim it as the very first in the Carolina TreeCycle program. While the tree’s provenance might make it priceless, the lumber they saved is worth tens of thousands of dollars due to the size of the slabs.

And, with the makerspace movement taking hold on campus, objects that are made from legacy wood now can be made right here, by students.

Treecycling is a burgeoning movement focused on reusing wood from urban, significant and historic trees in sustainable ways. Large trees in urban areas across the country often are removed and discarded, creating an excess of what is called “waste wood.” In Charlotte alone, Treecycle America estimates 9 million pounds of usable lumber is burned, mulched or left to rot in landfills every single year.

As the University arborist for more than 20 years, Bythell has been interested in the concept of treecycling for a long time. The University’s grounds department recycles and reuses nearly 100 percent of yard waste on campus, including fallen leaves, branches and small trees that are mulched at the Carolina North site. But trees larger than 35 inches in diameter can’t be processed here.

Treecycling would fix that while providing the University with useable, sustainable resources for on-campus projects — and for fundraising.

“People’s connection to the place, and to the trees, and all this — it’s humbling for me. And I say this all the time: There’s still probably 15 to 20 trees out there that predate the campus,” Bythell said. “That means every single student who ever went to UNC somehow experienced some of those trees”

– University Arborist Tom Bythell

“Every time we lose a big tree, I get tons of calls — what are you gonna do with the wood? And there’s an interest in it,” Bythell said. “The only problem is it’s not as easy as it sounds. You can’t just throw the wood in a corner and wait until it dries and then do something with it.”

Harvesting usable lumber from a felled tree takes time, space and money. Ideally, the tree first is felled correctly to preserve as much wood as possible, then dried in appropriate conditions for months or even years before it can be milled into workable lumber.

Talk turned to action when Michael Everhart came to campus. For the past year, Everhart, a graduate student in city and regional planning, has been discussing the possibility of a plan for campus trees with Bythell and BenDor, his adviser who is head of the land use and environmental planning specialization in the master’s program.

As a former woodworker, Everhart recognizes the losses Carolina suffers every time one of those trees goes through the grinder, so he devotes his time to connecting the many moving parts needed to honor the leftover wood.

“Specimen” trees are identified by size, age and overall rarity. But they must be dead or dying before they’re considered for treecycling, so gauging timelines is tricky. Although there was no finalized plan in place, the post oak forced the team to take the plunge with treecycling.

In Everhart’s plans, which he produced as part of his thesis, notable Carolina trees are monitored as normal by the arborist, removed to local mills once their times come and returned after they have been milled and dried. The lumber produced will be as unique as the trees it came from and will be used in a variety of ways, but much of it will go to BeAM makerspaces.

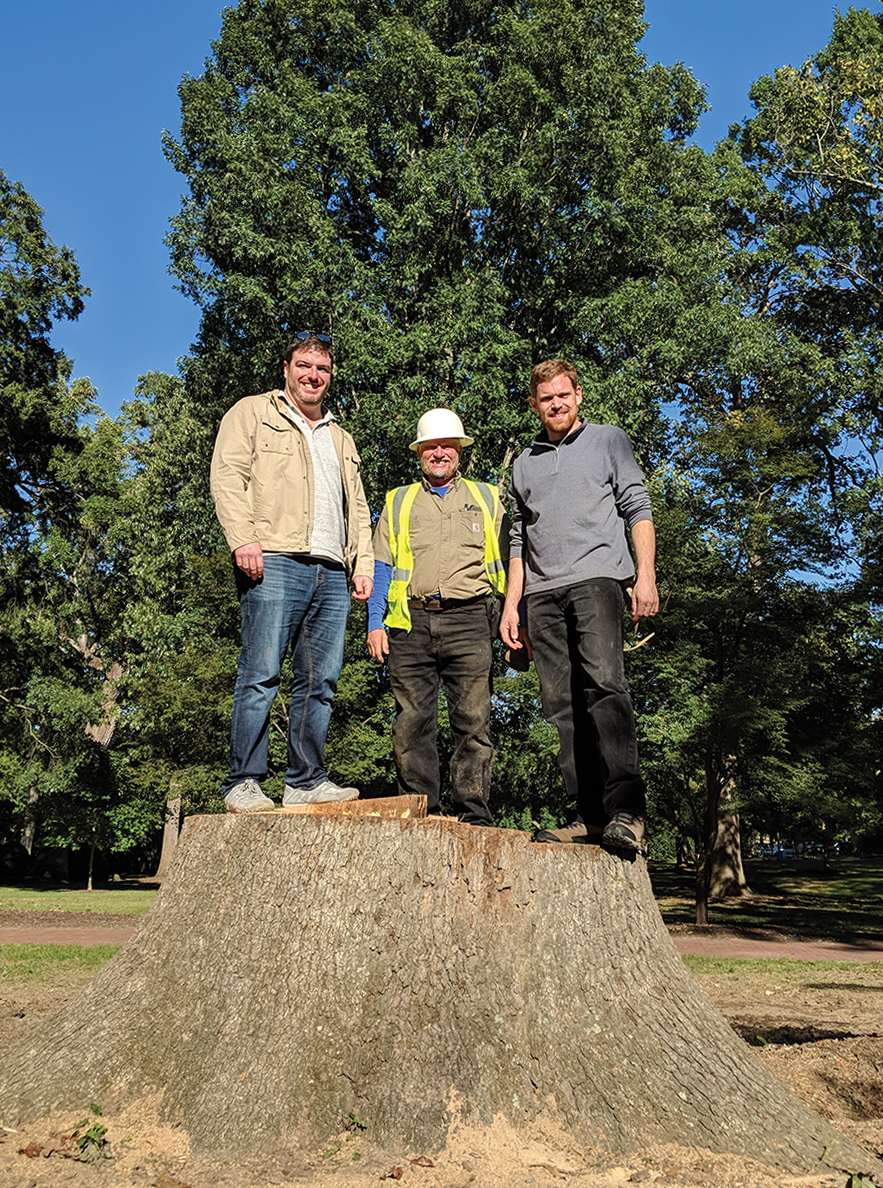

Ben Dor, tree miller Scott Smith and Everhart savor a moment on the stump. What to do with the wood? “It’s not as easy as it sounds,” Tom Bythell says. (Contributed photo)

BeAM was the brainchild of a small group of faculty and staff who believed there was a need for spaces on campus where students and the rest of the campus community could learn important skills they considered to be lost arts — metalworking, sewing, cooking and woodworking — and exercise their hands along with their brains. In its first two years, in three campus sites, BeAM attracted 4,000 users, including 160 classes that incorporated making into their curriculum.

Everhart, Bythell and BeAM technical supervisor D.J. Fedor already have started training an elite group of student employees who will make products out of the harvested lumber.

They are, for instance, making casings for writing pens from trimmings of the Davie Poplar, which are keepsakes for large donors to UNC.

“I wish I videotaped the students when they turned their first pen,” Fedor said. “It was that aha moment on steroids. They couldn’t believe they just made that, and you know, it’s just a piece of wood — and then you put a little polish on it, and their eyes just start shining. ‘I really just made that!’ It was really cool.”

The Carolina TreeCycle team is working with campus administrators to craft an official policy for this process. The plan is to use the saved wood for items to be sold in Student Stores, in larger pieces for fundraising by departments and other groups on campus, and for various installations across the campus.

“Imagine having a table that’s made out of a tree that outdates your university, or that was in a special location,” BenDor said. “That tree is going to be cut into firewood, made into mulch or made into beautiful pieces of furniture that will be in your home or office for the rest of your life, and maybe your kids’ lives. If we can use that to raise funds to create scholarships or other really useful purposes on campus, that seems like a win-win for everyone.”

In his time at UNC, Bythell helped one man trick his girlfriend into helping the grounds crew plant a tree so that he could propose underneath it. He provided another with shards of a recently removed maple after the man called him, sobbing, because the tree was where he met his wife, proposed to her and visited with her every year until her death. These stories and thousands more make him sure people will want to take a piece of campus with them.

“People’s connection to the place, and to the trees, and all this — it’s humbling for me. And I say this all the time: There’s still probably 15 to 20 trees out there that predate the campus,” Bythell said. “That means every single student who ever went to UNC somehow experienced some of those trees. The Davie Poplar is a good example of that.”

While he knows many people will want to take pieces for themselves, Everhart dreams of reusing all the wood for campus installments. He feels that intrinsic connection to the trees and believes the highest use for those so deeply ingrained in Carolina history is to allow them to remain a part of it.

“I would be happiest if every splinter of this wood somehow stayed on campus in a way that the community can continue to benefit from,” he said. “I think part of what makes them monumental is that, simply by recognizing their stature and their age, it gives people the opportunity to reflect on what it means to be part of a community that has been here for such a long time, and will continue to be here.”

— Adapted from an article in Endeavors, UNC’s research magazine, by Kasha Ely ’14

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.