College Stories 2011: Hard Work

Hard Work

by Megan Gassaway ’11

I would like to think I am capable of doing hard work. I have built houses with Habitat for Humanity and performed electrical and reconstruction work in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. But it was not until I went to Tanzania the summer between my junior and senior year of college that I learned the true meaning of “hard work.”

I would like to think I am capable of doing hard work. I have built houses with Habitat for Humanity and performed electrical and reconstruction work in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. But it was not until I went to Tanzania the summer between my junior and senior year of college that I learned the true meaning of “hard work.”

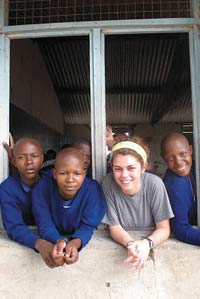

Receiving the Robin Clark Experience Scholarship for learning through doing from the UNC School of Journalism and Mass Communication, I traveled with a team of seven other UNC students to document water issues in Tanzania, Africa. I had traveled before. My passport bore the signs of a semester in Spain that included trips to Italy, Germany and Greece; but Africa was unknown to me. I had no idea what to expect, but everyone gasped in awe and amazement when I told them of my summer plans. I knew adventure lay ahead.

The documentary team and I began our studies in the former Tanzanian capital of Dar es Salaam and made stops in the cities of Moshi and Arusha before reaching the Maasai village of Mswakini. As documentarians, we always carried video cameras, audio recorders and other technological “necessities,” and as foreigners, we were constantly accompanied by a translator, the bridge between our English and the native Kiswahili and Maasai dialects. Needless to say, individuals we hoped to interview were hesitant to speak with us.

In an attempt to break the cultural and linguistic barriers standing between eight English-speaking UNC students and the Maasai villagers with whom we worked, the team decided that at each house we visited, we would ask to assist in a chore or daily activity. Armed with a new approach and our trusty translator and cultural tour guide Remini, a mother-figure for the team, the group and I traveled from our small hotel in Arusha through the endless savannah, past the isolated, cloud-encircled peak of Mount Meru and into the grasslands of Mswakini. As photographer, filmmakers, graphic designer, journalist and producer piled out of the car at the first home, Remini calmly explained our purpose: We were there to learn from them and hoped they would learn from us as well.

The day started out simply enough. A woman was refurbishing the outside wall of her mud hut. A plastic bowl sat beside her and a thick brown paste covered both the bowl and the woman’s arms. Being the team’s fundraiser and event coordinator, my hands were equipment-free and I was an easy target. She motioned me toward her, slapped the brown paste in my palm and guided my hand as I smeared the paste in thick, smooth strokes against the worn wall. Before I knew it, I was smiling as I followed the woman’s lead, refurbishing the outside of her home with a paste of cow dung, ash, water and soil.

The next few days were a blur of “everyday chores,” that included milking a cow, cleaning a goat pen and gathering corn from a field. The team and I traveled from home to home, partaking in work around the land and then doing interviews with the families. In Maasai culture, polygamy is accepted and in Mswakini it is the norm. This also dictates the living structure of families. A man lives in a “boma” with his multiple wives and children. In the center of each boma is an animal pen; mud huts, one for each wife, encircle the land. At one home, we arrived to find several mud huts and one wooden frame. The grounds around the unfinished hut were still covered with a tangled layer of vines and grasses, so one of the older women in the boma handed me a hoe and motioned toward the area around the hut.

I picked a patch where the weeds looked especially thick and set to work. Within 10 minutes, a pink blister had formed in the center of my palm.

“I would make a terrible Maasai wife,” I said jokingly to the translator and pointed at red bubble rising from where I held the hoe.

As Remini translated to the Maasai woman, the woman laughed and grabbed my hand. Looking at my blister, she shook her head and offered me a piece of roasted corn to make up for it.

At the time, I didn’t think much of it, but now I see the picture more clearly. When I look back, I see my white hand, soft and unblemished except for a fresh red bubble, in her dark hands, hard and calloused from a lifetime of labor.

That fall, I would return to UNC, to late nights in Davis Library studying for midterms and endless cups of tea to match the endless pages of articles written for my reporting class. The blister would fade and my life would carry on as usual. But for the Maasai women, what I experienced in Tanzania was only a fraction of their life. Each morning they awoke to a day of hard labor, working outside, hardening their hands with each swing of a hoe.

As I stress about deadlines and graduation, I can’t help but think back to those women and remember the true meaning of “hard work.”

Megan Gassaway ’11 majored in English and journalism and mass communication. The Charlotte native will teach elementary education in the Mississippi Delta with Teach For America after graduation.