60 Years and None Better

Unbeaten college basketball teams are rare. The 1957 Tar Heels knew they were good, and Lennie Rosenbluth recalls how they got that way.

by David E. Brown ’75

Joe Quigg was the top scorer in Brooklyn high school basketball in 1953. The next year, Pete Brennan was. Tommy Kearns was the best in the Bronx. Bob Cunningham was throwing ’em down in the Bronx, too, before he nearly lost the thumb on his shooting hand in an accident. So he specialized in defense.

They all went south, spirited out of the city to a place they’d never heard much about — certainly not on the subject of basketball. Kearns looked around him and marveled: “Trees!”

Lennie Rosenbluth had come down from the Bronx a year before the four Catholic boys. He is back in Chapel Hill now, and he has more trees than he knows what to do with. The tall picture windows separate the early October forest by inches from the den where he relaxes. But he can’t keep his impossibly long arms and those graceful hands still.

Coach Frank McGuire and his starters, from left: Joe Quigg ’57, Pete Brennan ’58 and Lennie Rosenbluth ’57; kneeling from left: Bob Cunningham ’58 and Tommy Kearns ’58. (UNC photo)

“I tried every which way, over my head and everything else,” he explains. “But then I started to really” — he pauses — “how do you shoot a basketball? And the idea came from watching baseball pitchers.” Over and over, the fluid rise of the arms, the snap of the wrist.

“If you want to throw a baseball straight, you have to throw it and your hand has to go out. Where your hand goes, the ball goes. That was the first thing that hit me. And if you throw a baseball straight, your elbow is in. So then I started shooting like this, following through with the hand. Wherever the hands go, that’s where the ball is going. And I got better and better.

“I had almost perfect form.”

It did not come easy. Not for the young Rosenbluth, not for the Carolina team that finished with 32 wins and not one defeat 60 years ago. As Kearns said, “We won too many games that we should have lost.” Sometimes they made it look awfully easy. And when it wasn’t, they always reached deeper and made it go their way.

What happened in March 1957 and in the months leading up to it did not necessarily make North Carolinians crazy for basketball, but it made sure they stayed that way. As sports writer Frank Deford said: “Before this weekend, ACC basketball was popular as a sport; after this, it was woven into the fabric of North Carolina society.”

Consider some of what happened to cause a ho-hum pastime between football seasons evolve into the mania that oozes from every pore of this campus: An elite coach needed to get out of the big city; his disabled son, too; N.C. State took a pass on one of the greatest players the game has known; a controversial call could have ended the championship run back in the ACC tournament; out of 32 games the Heels played, only eight were at home (and seven were in Reynolds Coliseum); an aspiring coach — a nobody in the game — rubbed the right elbows in Kansas City.

At the climax: triple overtime wins on consecutive nights; a bad pass to Wilt Chamberlain; players who defined the word “team” as the star spent the final 17 minutes on the bench.

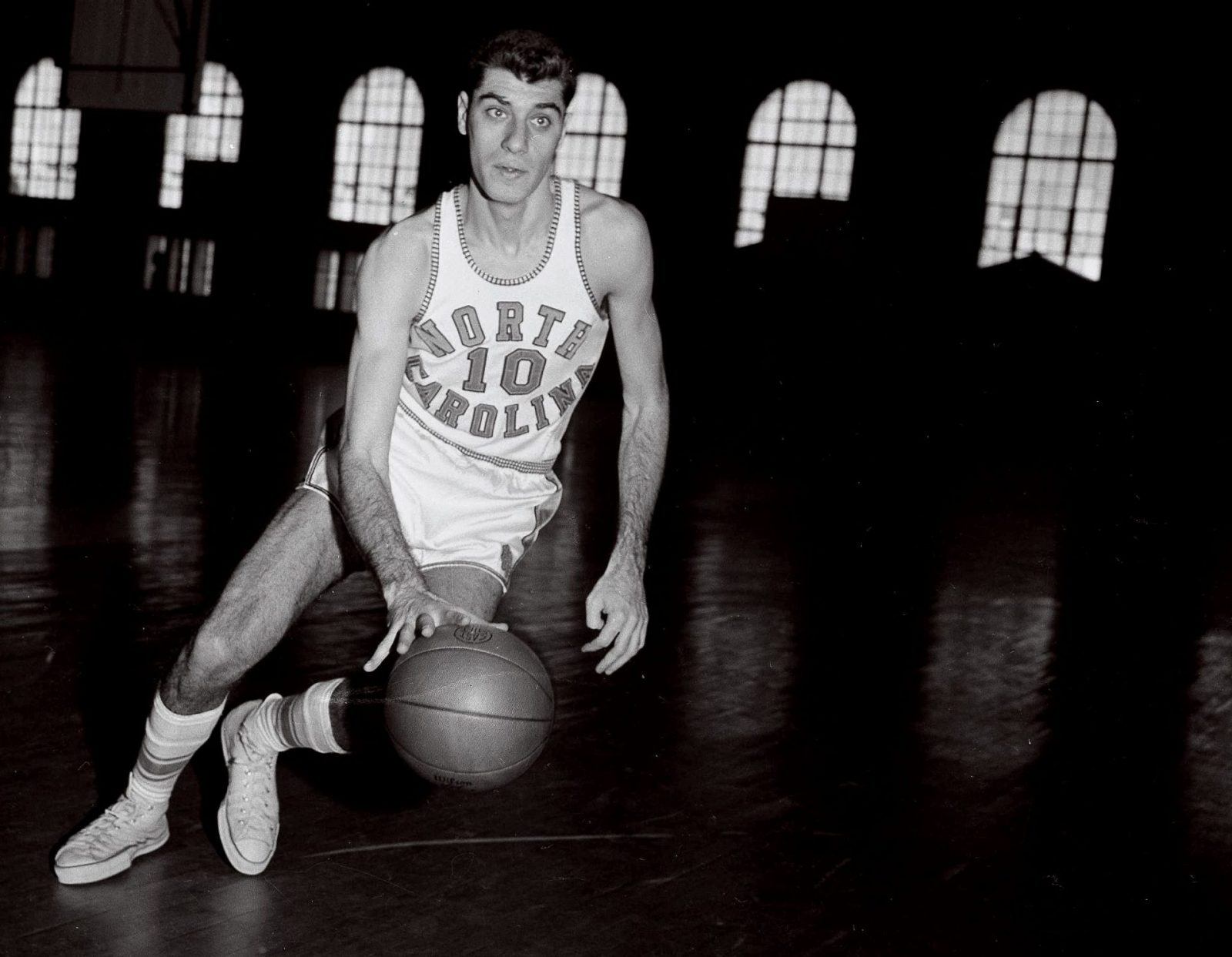

Lennie Rosenbluth, on the move. “I had almost perfect form,” he said about he shooting technique he developed after a lot of practice. (UNC photo)

The operator

Chapel Hill was quite the sports town during World War II. The Navy’s preflight school filled out its baseball team with Ted Williams and other big-name major leaguers, and Kenan Stadium saw the likes of Otto Graham and Bear Bryant. Usually overlooked in that list is Frank McGuire, an officer in the school who helped coach the high school basketball team while he was here — the only one of them who came back after the war. The town had left an unforgettable impression on him.

McGuire developed into a big shot in New York as coach of St. John’s, but by the early 1950s, basketball in the city’s colleges was wracked by scandal, and he decided his best course was to seek his fortune elsewhere. He thought, too, of Frankie, his son with cerebral palsy; a city apartment was a terrible place for him, and a better climate, room to breathe and a backyard swimming pool beckoned from McGuire’s war days.

He was an operator — all you need to know is that he attracted a station wagon full of big city stars who would find the South a decidedly foreign environment in the days before the civil rights movement, and he shepherded them through the culture shock. He liked nice restaurants and being seen in expensive suits. McGuire did the screaming and left the tactics to a master of the fine points of the game, James “Buck” Freeman, who was his assistant at St. John’s and came with him to Carolina.

McGuire did not let his players forget the 77-56 whipping they took from rival Wake Forest in the 1956 ACC tournament.

In the fall, he told Kearns, Quigg and Brennan that they would have plenty of chances to shoot when the defense collapsed on Rosenbluth but that their job one was to get the ball to Lennie — after all, he had averaged 27 and 25 points per game the two previous seasons.

McGuire’s touch had a special impact on Kearns that year.

“If you look at my sophomore year, I did not have a great year, and I think that was a testament to Coach McGuire,” he recalled. “He knew I was getting a little bit out of control, and I think that coaches have a way of dealing with that, and the way they deal with it is they don’t play you as much as you think you should be playing. That really sent me a big-time message. I got myself straightened out, came down off my perch and moved on, and we had a great year.

“But that transition from my second year was what he did to me and for me. I’ll be eternally indebted to him for that. I didn’t think so at the time, but it was a very, very wise move.”

As captain, Rosenbluth called a preseason team meeting, pulled out the schedule and said he couldn’t find a team on there that could beat them. Only internal dissention could do that, and he kept calling those meetings every week.

“If you think I’m shooting too much, let me know.” He would average 28 that year.

As the season reached the midpoint, McGuire proved no match for his players’ relentless optimism. Down four to Maryland with time running out, he huddled them and told them to be gracious in defeat. After two overtimes, Maryland was beaten by four. Rosenbluth reminded his coach that 15 more wins would get them where he knew they were going.

Rosenbluth uses his long reach against Duke on Feb. 9. Carolina took it, 75-73, one of three over the Blue Devils. No. 20 is Bob Young ’57, one of five surviving members of the team. (North Carolina Collection photo)

Couldn’t catch

He is 84 now, and after a full career teaching history and coaching in Florida, Rosenbluth is a familiar face in the Smith Center. Current players don’t have to be told more than once about his place in the program — his numbers, even after all the talent that has passed through in 60 years — are still right at the top of the list.

“When I was a kid, when I was 10 years old — this was during World War II, so it would be about 1943 — my father was gone into the war, all my uncles were gone, so there was no men around. I couldn’t catch a ball. Honestly, I could not catch a ball.

“I went to the Boys Club camp for one week, and the cabins were set up where everybody played on a softball team. I was forced to play, but I really had no coordination. They said, you can’t play anywhere else, so pitch. I remember this distinctly because it was traumatic at the time. The bases were loaded and I was pitching, and the hitter did a little pop fly to the pitcher. I didn’t catch it. It went off my glove and traveled over to the side, and he hit a home run off a little pop fly.

“And everybody started laughing, and I remember you know, very sad, crying, and the counselor said, don’t worry about it — you’re leaving in four or five days, no one will know about it.” He laughs about it now himself.

“It bothered me, so when I got back to New York I started throwing the ball against the wall and catching the ball and catching the ball and learning how to catch the ball.”

By seventh grade, he was a fixture on the playground courts.

“I really liked the game and I really wanted to play, so just about every day I’m playing basketball. In the eighth grade, I go out for the junior high school team — I’m not good enough, I don’t make it. I’m still playing outside in the park all the time.”

In the 10th grade, Rosenbluth tried out for the junior varsity. “The coach did something that really hit me. He took a rim, and he showed the rim to everybody, and he said, ‘You know how big this is?’ ” He’d discovered that the rim’s circumference is twice that of the ball. “Now, that’s pretty big. I always remembered that.”

He didn’t make the team in the 11th grade either. It was back to the park.

“Teams I was playing against were all older people — ex-college players. Someone must have asked the coach, ‘Why isn’t he on the team?’ because he called me back in January of my junior year to come back and try out for the varsity again. This time, I tried out and made it and became a starter on my high school team.”

He played maybe eight games, but two of them were in the city tournament in Madison Square Garden. After one of those games, he recalled: “There were two ways to go to get out of there — left exit, right exit. This is how things change your life.” He took the right, and there stood a man named Harry Gotkin.

“Harry said, ‘I like the way you play, and I think you have some potential.’ ” Gotkin recruited players for a summer circuit in the Catskill Mountains. The teams had mostly college players, and Rosenbluth knew he wouldn’t play much. But fate intervened again. Three players on his team were hurt in a car accident, and now they needed him.

“Something happened that summer. I learned the idea of spacing, the idea of you don’t have to shoot fast. I saw the court better. Everything seemed to fall into place when I was playing, and I played very well. I saw the court differently, the shot I was making completely changed. I went from being part of the team to the high scorer and top rebounder. I saw the basket differently. I don’t know how to explain it.”

He found himself playing against a team coached by Red Auerbach.

“And I had a great game against them. I had two games against them. I really, really developed. Summer is over, I’m getting ready to start my senior year, I get a call from Red Auerbach. He wants me to come up to Boston and work out with the Celtics.

“My roommate was Bob Cousy. I’m working out with the Celtics. High school started, I’m still in Boston with the Celtics.”

New York suited the Tar Heels: Cunningham, Rosenbluth, Kearns, Quigg, Brennan and McGuire mug for the camera on the day before they played Yale in the first round of the NCAA tournament. They had beaten NYU in the city in December. (AP photo)

Case — then McGuire

Rosenbluth just wasn’t meant to play high school basketball. At the start of his senior year, the coaches all went on strike over low pay. He started playing for a YMCA team.

“When the strike was over, I didn’t go back. I didn’t want to. I was playing in the Y league, which was great, and I felt that I was getting much better doing that than playing high school basketball.”

Plus, Auerbach had arranged for him to go to games in the Garden for free. One night, Harry Gotkin spotted him and beckoned him to a seat with a group of men that included Frank McGuire. “So I met Frank McGuire. I used to sit in his box, and occasionally he would be there, too.”

Rosenbluth listened in on shop talk — including shooting technique. “Shoulders square to the basket. I listened.”

Everett Case, the legendary N.C. State coach, got wind of Rosenbluth when he was recruiting Gotkin’s nephew. He scouted Rosenbluth at the Y, and when the Wolfpack came to the Garden to play, Case let him work out with his team.

“And I played fairly well against his varsity. I had no trouble scoring against them.” Case invited Rosenbluth and his dad to Raleigh to see the Dixie Classic holiday tournament. Lennie had never been south before, but suddenly he and N.C. State had a mutual interest. In April, they went back to see the campus. Rosenbluth thought it was a done deal, but Case didn’t like his showing in a workout with the team, and the scholarship offer vanished.

“I went back to New York, and about a day later Frank McGuire calls me and says, ‘I need to talk to you.’ ” He’d heard what happened at State. “He tells me, ‘No one knows about this. I’m leaving St. John’s. I really need you. I’m gonna build a program, and you got to be part of it.’ I said, ‘Coach, I’ll go wherever you go.’ ”

Rosenbluth, left, and Quigg work Chamberlain together in the title game. The Kansas center was held to 23 points, 6 under his average. (NCAA photo)

Kansas City

Everett Case’s N.C. State teams were the ones Carolina chased in the ’50s, but by the championship season the more heated rivalry was with Wake Forest, which until 1956 was located in the Wake County town of that name, less than 40 miles from Chapel Hill. “Wake hated us. Hated us,” Rosenbluth said. “They wanted to beat us so bad.”

The Heels beat Wake four times that year. The colorful coach Bones McKinney ’48, then an assistant coach at Wake, swore that their rival spied on their practice before the third of those, at Wake in February. But it was the last play of the fourth meeting, in the semis of the tournament, that has been argued ever since.

Down by one with a few seconds left, Rosenbluth took a feed from Cunningham, stepped into the lane and whipped the hook shot, but in the process he gave the Wake defender a hard left shoulder to the chest. It was a charge or a blocking foul, depending on your loyalty, but the ref called the latter, and Carolina won by two. If it had gone the other way, a 25-1 record wouldn’t have mattered to the NCAA tournament — the season would have been over because in that era only conference champions could advance.

Carolina ran through three regional NCAA games with little trouble. The trip to Kansas City for the finals should have been a short one: The Heels did not play well against Michigan State. Kearns and Quigg were off, but Rosenbluth scored 29 and Cunningham scored his career-high 21, and they pulled it out in three overtimes.

Kansas, playing essentially a home game, did not have the distinction of being unbeaten and couldn’t come close to matching Carolina’s personnel, but it had 7-foot-1 Wilt Chamberlain, the kind of talent the college game had never seen. McGuire told the team: Kansas cannot beat you; Chamberlain can.

“We played zone the whole time with myself playing Wilt Chamberlain and all four of the guys helping out,” Quigg remembered. “I could not have guarded Chamberlain by myself. You don’t play an athlete like that by yourself.”

The Heels shot 47 percent from the field to Kansas’ 32, and they contained the big guy. Rosenbluth had a good seat for all the overtimes, having committed too many of what he called “stupid” fouls, but Quigg, who always had dreamed of making a last-second shot to win a big one, settled for two cool free throws with six seconds left. The Jayhawks’ pass in to Chamberlain, maybe five feet out from the basket, was a foot too low. Quigg slapped the ball to Kearns, who knew when he heaved it into the rafters it wouldn’t come down in time.

“Early on, our third or fourth game we go into overtime at South Carolina,” Kearns said. “Then the three games with Wake Forest, I think, the biggest spread there was something like five points. They were very, very tough games. Then being at Maryland and winning there was kind of a luck of the draw.

“And then of course when you get into the playoffs the game against Michigan State where Pete Brennan got a rebound, Johnny Green was on the foul line, they’re up by two. He makes one of the foul shots, and the game’s over. He misses, and Pete gets the ball, dribbles down the court, puts it up, bangs it, and we go to overtime.

“But you never know. As we found out last year. In a lot of ways, I’d rather be lucky than smart or a lot of other things.”

Broadvision

The problem with putting games on television in 1957 was that the radio people didn’t want to share the market.

Billy Carmichael ’21, then the vice president of what was called the Consolidated University (now known as the UNC System), gets most of the credit for solving that problem. First came an experiment with live TV that had no audio — viewers would have to tune in to the radio.

One day, Carmichael and then-President William Friday ’48 (LLBJD) went down to Woollen and chiseled a hole in the wall on the second floor overlooking the court. They stuck a limited-movement camera in the hole, and on Feb. 9, a two-point win over Duke had a home audience that could see and hear. They aired what they called “Broadvision” again four days later, when the Heels played Wake Forest.

Castleman Chesley ’36, who had tinkered with televising football games, put together a three-station network to air the NCAA tournament regionals in Philadelphia. He expanded that to 11 stations in Kansas City for the semis and finals, including a broadcast back to North Carolina.

Stay-home basketball was born. The Carolina players didn’t know until after the title game that they’d been on TV back home.

The impact was immediate. “When we came back on that Sunday, we figured, you know, there’d be a few people to greet us,” Quigg said. An estimated 10,000. Traffic was backed up from Raleigh-Durham Airport to Chapel Hill. There were people on the runway.

‘I played basketball’

It was, to understate, a different time. Team manager Joel Fleishman ’58 tossed the championship trophy into the laundry bag. The players were astounded when people back home wanted their autographs. The championship rings, now a standard, were unheard of then, and the ’57 Heels wouldn’t get rings until 1995.

The core of the championship team, minus Rosenbluth, was back in the fall with high expectations. Quigg broke his leg in the preseason and never played again. Brennan was ACC Player of the Year, and Kearns was second-team All-American. Carolina lost six in the season and came up short on the ACC championship game.

Lennie Rosenbluth at home in Chapel Hill. “I played basketball. I didn’t write music or write a book or anything. I just played basketball. I loved playing, and I had a great time, and I loved playing for coach. I really liked him. Here, I’m a kid from New York, I got a free college education, a school as great as Carolina.” (Photo by Anna Routh Barzin ’07)

One of the Kansas alumni who had gone away unhappy the year before was a young Dean Smith, at the time an assistant coach at Air Force. Head coach Bob Spear had taken Smith with him to the tournament, where they crowded into a hotel suite for three nights with three other basketball people — one of whom was McGuire.

The downhearted Smith accepted McGuire’s request to address the team after the game, as recounted in Adam Lucas’ book, The Best Game Ever. Then he recommended the steakhouse where they went to celebrate.

Back home, assistant coach Buck Freeman was out; his battles with alcoholism had resurfaced in the pressure of the championship season. McGuire gave the job to Smith, and the rest of that is …

The dapper one had played loose with NCAA rules governing entertainment of recruits and expenses for players’ families, and in 1960, UNC was under investigation. McGuire’s trusted scout Harry Gotkin was caught up in it, and in 1961, Carolina was placed on probation. McGuire left for the pros, where he coached Chamberlain. In the 1970s, he got under Carolina’s skin as coach at then-ACC member South Carolina — where his best teams were anchored by New York City boys and where he rehired Freeman.

Lennie Rosenbluth — who couldn’t catch a ball, who taught himself to shoot, who had an epiphany about the game one summer that he can’t explain — still holds the Carolina scoring average records for career and for a single season. He has the most points in a season, most in a regular season ACC game, most in an ACC tournament game, most in the tournament for a career. He has four of the Tar Heels’ six highest-scoring game performances, the most 40-point-plus games. He ranks fourth in career points in three years — players were required to serve a year on the freshman team in those days — behind three latter-day players who played four years. All of the Carolina scorers who are close to him on the various lists played substantially more games than he did. (He is not in the top 25 in field goal percentage.)

“I played basketball. I didn’t write music or write a book or anything. I just played basketball. I loved playing, and I had a great time, and I loved playing for coach. I really liked him. Here, I’m a kid from New York, I got a free college education, a school as great as Carolina.”

“I worked for Merrill Lynch in Greensboro for 10 years,” Kearns said, “and everybody knew me. The problem with that, of course, is I was really more interested in talking about stocks than I was winning a national championship, but it was clearly a door open for me. Wilt and I became really, really good friends.” He retired at 49 but keeps his hand in the investment business.

Joe Quigg went to dental school and gave the Army three years, then practiced in Fayetteville until 2000. He, too, still helps out with others’ dental practices there. He and the others always got a kick out of McGuire’s stories about a college teammate of his, a defensive wizard named Rip Kaplinsky, whose name he invoked whenever the Heels weren’t hustling. Later they got to meet Kaplinsky, and Quigg busted out laughing — he stood about 5-foot-7.

When Quigg’s daughter was enrolled at Appalachian State, Quigg went to meet ASU Coach Bobby Cremins, who had starred for McGuire at South Carolina. Cremins told him that Quigg and his teammates had become Rip Kaplinsky when McGuire needed to fire up the Gamecocks.

Rosenbluth said, “We have five players still, which is fantastic” — Kearns, Quigg, Tony Radovich ’57 (’60 MEd) and Bob Young ’57. “We’re more like brothers than teammates, we have been for a long time. We care for each other, we find out when someone’s sick.

“We all graduated, we were all good people, and we all contributed in life one way or another. And we had an undefeated season. Except for UCLA, who [went unbeaten] four times, there’s only been three other schools, and we’re one of them. It’s a proud achievement.”

David E. Brown ’75 is senior associate editor of the Review.

Watch the championship game at bit.ly/1957champs. Rosenbluth goes back to Kansas City at bit.ly/RosenbluthReturns. See more recent player interviews at bit.ly/McGuireMiracle.

Bob Young made plays on the ’57 team. These days, he believes in the power of poetry. Read about it at bit.ly/poetry_project.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.