Admirable

Kristin Acquavella ’93 is one of 22 active female admirals in the U.S. Navy. To get there, she relied on what she learned while winning four national soccer championships at Carolina.

By Tim Crothers ’86

She played with the boys in Aguadilla, Puerto Rico.

She played with the boys in Lanham, Maryland. She played with the boys in Norfolk and Key West. So why not play against boys in Italy?

It was 1980 in Gaeta, a seaside town midway between Rome and Naples. Kristin Acquavella, the daughter of the dental officer on the Navy’s 6th Fleet flagship, unpacked her bag at yet another port. As a third grader, she attended the Department of Defense school, where Navy parents coached all of the sports. One of them, a native Italian, coached the Navy soccer team and arranged some games against local youth teams. Boys.

Girls didn’t play much soccer in Italy back then.

Acquavella had played on Navy teams at all of her father’s far-flung posts, where sparse numbers dictated that boys and girls always competed together in sports. Even though she had red pigtails and soccer shorts several sizes too big, Acquavella didn’t see herself as any different from the boys on her team.

But Italy did.

Before one game, when both teams marched out to the center circle, a local boy presented Acquavella with a bouquet of flowers because, you know, that’s what Italian guys do. As her male teammates took their positions, Acquavella lingered behind wondering what the heck to do with the flowers, a worldly 9-year-old girl fixated upon one question: Why?

Life Lessons

Kristin Acquavella ’93: “Every day at Carolina I learned humility. You play with these amazing players who are the best in the world at their sport, and yet they’re so humble about everything that they do because they understand that their success depends on the entire team.” Photo: AP Images/Marco Garcia

The Navy brought Acquavella back to Virginia Beach when she was in the seventh grade. By then she had identified soccer as her calling. But the local club soccer scene at the time wasn’t strong, so her parents shuttled her three hours each way to Northern Virginia, where most weekends Acquavella was exposed to a level of talent she’d never seen. She attended the same regional camp as a wunderkind named Kristine Lilly ’93, who was promoted to the U.S. national team before the first training session ended. She was a teammate on the Braddock Road Shooting Stars with a dynamic striker named Mia Hamm ’94, who with Lilly would start for the national team as teenagers.

One day at soccer practice, Acquavella’s coach brought his daughter, Wendy Gebauer ’89, to demo some skills for the team. Gebauer foot-juggled a softball 100 times. Acquavella was mesmerized. The two became pen pals, and soon after, when Gebauer chose to join the emerging soccer dynasty at UNC, that became Acquavella’s dream as well.

Because his Tar Heels had won seven of the sport’s first eight national titles, UNC women’s soccer coach Anson Dorrance ’74 could choose the top five players in the world to join his 1989 recruiting class. Those five players were Lilly and Hamm, Julie Foudy, Rita Tower ’94, and Sarina Wiegman ’93. Dorrance informed Acquavella that, unfortunately, she was number six. Acquavella admitted she didn’t have a Plan B.

But Foudy decided to play for Stanford University, turning down UNC at a time when great players didn’t do that. “Kristin probably wakes up every day thanking her lucky stars that Julie Foudy chose Stanford,” Dorrance said. “If Foudy hadn’t rejected us, there’s no telling how that might have changed Kristin’s life.”

When Acquavella arrived in Chapel Hill in August, she had no idea the life lessons awaiting her. Among the first activities she did with her new teammates was a fitness challenge called the Cooper test, which requires players to run as far as possible around a track in 12 minutes.

Acquavella said she had heard horror stories about girls throwing up during the test. She remembered Tracey Bates ’89 pacing the players by running backwards on the track, cheering on her teammates. Dorrance yelled to Bates to pick it up or she would not complete the required distance needed to pass the test. “What an amazing example of leadership at the risk of her own success,” Acquavella said. “That really stuck with me.”

On the field Acquavella was versatile. She could play as a tireless midfielder, a productive forward, or a responsible outside back. “Her red hair was just all over the field,” teammate Julie Carter ’92 said. “Her skill level was solid. Her attitude was solid. Her sportsmanship was solid. She was admirable in every way.”

Acquavella would become Dorrance’s troubleshooter off the bench, operating under the radar on some of the greatest teams in UNC history. “Kristin had an incredibly galvanizing leadership voice,” Dorrance said. “She wanted to serve the program instead of any personal agenda, which is so incredibly rare these days when it’s all about how many likes you have on Instagram, but she was cut from a different cloth.”

Acquavella scored 11 goals in her UNC career. She doesn’t remember any of them. Ask her what she recalls most from her four seasons on the field and she says, “the loss.” The Tar Heels lost one game in her career, an overtime defeat at Connecticut in 1990 that snapped UNC’s 103-match unbeaten streak. “It was a miserable 13-hour bus ride home,” Acquavella said. “All I wanted was to play UConn again. Later that year we crushed them 6-0 in the national final. That’s what I remember.”

Acquavella, center, said her dearest recollection of UNC soccer didn’t occur on the field. It was an impromptu camping trip with four of her teammates, above. “What makes Carolina special are the personal relationships,” she said. Photo courtesy of Kristin Acquavella ’93

But Acquavella’s dearest recollection of UNC soccer didn’t occur on the field. It was an impromptu camping trip with teammates Carter, Hamm, Tower and Sarah Ludington ’92, when the five women were so comically clueless about the great outdoors that they had to enlist a troop of Boy Scouts to help them set up their tents. “What makes Carolina special are the personal relationships,” Acquavella said. “I was part of four national championships, and I don’t have a single ring to show for it. I gave them all away.”

At Carolina, Acquavella described herself as a “soccer nerd,” which explains why after her freshman year she asked UNC assistant coach Bill Palladino ’73 if she could help with the UNC summer soccer camp. “Kristin said, ‘I want to work camp, but I don’t want to be on the field, I want to work in the office and help you run it,’ ” Palladino recalled. “I said OK, and boom, before I knew it, she had her own staff, and she organized the office, and I’m thinking this is the way I’ve got to do camp from now on.”

“Running a summer soccer camp is all about taking care of logistics and solving problems,” Dorrance said. “Kristin was an incredible problem solver.”

Before her senior season, Acquavella was elected captain alongside Hamm and Angela Kelly ’94. “I think that my role as a captain was the dot connector, the bridge between the starters and the reserves because it got hard when you reach the postseason and half your roster has to watch from the stands,” Acquavella said. “I was a teammate who always kept sensitivity to the human piece of the game.”

She didn’t fully grasp at the time that she was training for her future.

“Going to UNC had a tremendous influence on who Kristin would become,” her father, Richard Acquavella, said. “Anson ran a very tight ship, a very honest and upfront organization, and he certainly instilled a work ethic in his players, a dedication to duty to whatever the mission was. Kristin carried all of that over into her military career.”

Wait! What? Her military career? Turns out Acquavella is now an admiral in the U.S. Navy, but don’t expect her to dwell on that. “She’s not a self-promoter,” Gebauer said. “A lot of her UNC teammates don’t even know.”

“The next thing I knew”

Acquavella’s father Richard, a captain with 29 years of service in the Navy, was on hand to commission Acquavella to ensign (top) and to captain (bottom). Photos courtesy of Kristin Acquavella ’93

Acquavella’s grandfathers and father all became dentists after graduating from Georgetown University’s dental school. Richard Acquavella spent 29 years as a Navy dentist, rising to the rank of captain. The easy story is the one about how a doting daughter dreams of following her father’s footsteps into the Navy, anchors aweigh, fair winds and following seas, blah, blah, blah … that ain’t Kristin Acquavella’s story.

“I remember in high school my dad sitting my brother and me down at the kitchen table and asking us two questions,” Kristin recalled. “ ‘First, do you want to be a dentist?’ We both said no. ‘Second, do you want to go into the military?’ We both said no.”

Acquavella came to UNC for one reason: SOCCER. Period. “Soccer was my family,” she said. “It was my passion and my heart.”

So how did she end up in ROTC? Good question. Even after 29 years in the Navy, Acquavella can’t really explain why she initially decided to sign up for ROTC, except that one day during her sophomore year at Carolina, she suddenly realized she wasn’t going to be a professional soccer player. She knew she had to do something. She didn’t really have a Plan B. “Growing up as a Navy brat, I guess I was predisposed to the idea of military service,” Acquavella said, “and I thought becoming a pilot might be cool.”

At first she wasn’t all that committed. After Acquavella joined the Air Force ROTC — because its armory was the closest to her dorm — an acquaintance in Navy ROTC questioned why she’d chosen the Air Force instead of the Navy. “I told him, ‘I don’t know, whatever, if you want me in Navy ROTC so badly, why don’t you do the paperwork for me?’ ” Acquavella recalled. “So he did, and the next thing I knew, I was in the Navy.”

During her initial days in ROTC, she practiced drills on the field behind Avery Residence Hall, where she roomed with Carter. “Kristin started ROTC later than most of the other cadets, so she was catching up,” Carter said. “She had no idea what the hell she was doing. She was about-facing the wrong way, turning left when everybody else was turning right. It was hilarious to watch.”

Acquavella endured seven weeks of officer boot camp the summer after her sophomore year. She learned the Navy’s etiquette, customs and courtesies, and earned an ROTC scholarship that would replace her partial soccer scholarship and pay for the rest of her education at UNC.

On Dec. 21, 1993, Acquavella stood in the Naval Armory for her commission into the U.S. Navy. Dorrance, Palladino, Gebauer, Hamm, Lilly and many other Carolina teammates were there to support her. Capt. Richard Acquavella administered the oath of office to his daughter, Ensign Kristin Acquavella. It was only a month after she’d won her fourth national championship with the Tar Heels just down South Road at Fetzer Field.

“Worst sailor ever”

Turns out Acquavella had one teeny problem with the Navy. “I get horribly seasick,” she admitted. “I’m the worst sailor ever. Getting on ships, I felt crappy all the time. I could barely hold down food. There were plenty of days when I wondered, ‘What was I was thinking joining the Navy?’ ”

Acquavella’s response to the nausea harks back to the Cooper test. “You’re trained as an athlete at UNC that the mission must go on,” she said. “Carolina soccer fitness days prepared me for how to function through misery.”

Dorrance agrees that Acquavella’s indoctrination to her current career began at UNC. “Honestly, what I remember most about Kristin as a player is how unbelievably coachable she was,” he said. “As you gain status in the military, it is largely based on your capacity to follow orders, which has served her well in the Navy.”

Acquavella is a supply corps officer, a position that runs the gamut of logistics from tactical to operational to strategic, not unlike UNC soccer camp.

Rear Adm. Ken Epps ’02 (MBA) has known Acquavella since 1994 when he taught her at Navy Supply Corps School. “Kristin has this infectious attitude that creates cult-like followings,” he said. “There’s no doubt Anson Dorrance conveyed some of his DNA to her in the way they both get people to willingly do hard things that aren’t always fun.”

Inside the Navy supply community, Acquavella has earned the nickname Coach. “She’s one of the most sought-after mentors because she will bend over backwards to assist anyone who seeks her advice,” said Navy Capt. Julie Treanor. “Kristin thinks like a coach and is very good at building teams that buy into this esprit de corps that’s part of her personality.”

Treanor said Acquavella once talked her out of quitting the Navy. She has since followed Acquavella through four tours.

“Kristin likes to fix broken-winged birds,” Treanor said. “She doesn’t give up on people. It goes back to her experience getting on the UNC soccer team. She fully understood that she got lucky. She’s an underdog’s champion, because at UNC she was once an underdog herself.”

Acquavella has never forgotten the lesson of competing alongside soccer icons like Hamm and Lilly. “Every day at Carolina I learned humility,” Acquavella said. “You play with these amazing players who are the best in the world at their sport, and yet they’re so humble about everything that they do because they understand that their success depends on the entire team.”

The UNC brand also came in handy when Acquavella first inquired about playing soccer for the All-Navy team. “I phoned the coach and introduced myself, and he said, ‘Well, we’ve already been training for two weeks, we’re really good, really fit, we don’t really have a place for you,’ ” Acquavella recalled. “Just before we hung up, he asked if I’d played in college, and I told him I played at UNC, and then he said, ‘Well, we’ve only been training for two weeks, we’re not that good, not that fit. When can you start?’ ”

A trailblazer

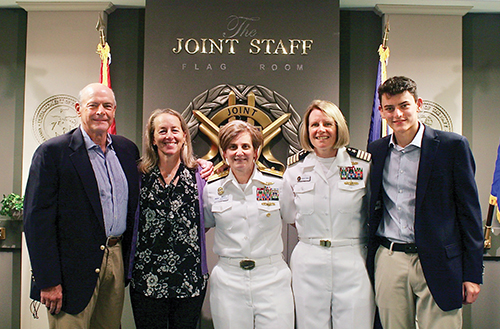

Left to right: Bill Palladino ’73, assistant UNC women’s soccer coach from 1980 to 2019; his wife, Wendy Gebauer Palladino ’89, who once wowed a young Kristin Acquavella by foot-juggling a softball 100 times; Acquavella ’93; her spouse, Capt. Wendy Towle; and Zach Palladino at the ceremony for Acquavella’s promotion to admiral on Sept. 2, 2021, in the Pentagon’s Joint Staff Flag Room. Photo courtesy of Kristin Acquavella ’93

If dealing with seasickness wasn’t enough, during her first tour Acquavella also managed being the only female on her ship. “She’s a woman, in a man’s world, who believes that it’s not always the shiniest penny that is the best person for the job,” Treanor said. “She does everything she can to make sure the most qualified person gets the nod.”

Acquavella remains sensitive to what she calls the human piece of the game. “Maybe I did it subconsciously at UNC, but I certainly do it consciously as a naval officer,” she said. “As you get more senior and your sphere of influence grows, you’re always going back behind with that silent hand checking on people to make sure they have that sense of belonging. That’s how you build great teams.”

Described as both demanding and compassionate, Acquavella’s leadership can take many forms. “She could always tell if I was having a bad day,” her former chief of staff John Hamilton said. “She had an espresso machine in her office, and she knew when a coffee break would really cheer me up.”

“She’s driven by her humility, and more than anyone I know, she puts the team and the mission before herself,” Epps said. “Her side hustle is that she’s as good a sponsor of younger talent as anybody I know. She’s a trailblazer who never hesitates to send the elevator back down to bring up more trailblazers.”

Acquavella is a trailblazer on multiple levels, including her sexuality. “It’s definitely not something I lead with, just like I don’t wear four national championship rings on my hand, but I certainly don’t hide from it,” Acquavella said. “When people ask me, ‘So, what does your husband do?’ I say, ‘Well, actually my wife, Wendy, is a Navy captain, and I’m proud of that.’ People can get sidetracked with that narrative, but lucky for me I haven’t been discriminated against by my sexuality for promotion.”

Epps repeatedly used the word “pioneer” to describe Acquavella. “There are very, very few nonwhite males in the position that she’s in, and she is also the only ‘out’ admiral I know in the Navy,” Epps said. “Kristin is not the type of person who wraps herself in the rainbow flag, but she quietly leads in that space. With her public embrace of who she is, she very decisively has let it be known that you can be who you are and still succeed at the absolute highest levels in the United States Navy.”

“As you get more senior and your sphere of influence grows, you’re always going back behind with that silent hand checking on people to make sure they have that sense of belonging. That’s how you build great teams.” — Kristin Acquavella ’93

Why?

Capt. Richard Acquavella presided over the first six promotions of his daughter’s Navy career, from ensign at the UNC armory to captain on a sandbar in Kane‘ohe Bay, Hawaii, in 2015. On that day, Richard gave Kristin his eagle that signifies the rank of a Navy captain, which she wore for six years until her promotion to admiral on Sept. 2, 2021, at the Pentagon.

“This is usually a jinx for officers, but so many people pulled me aside over the years and told me, ‘Kristin’s going to be an admiral someday,’ ” Richard said. “For her to actually outrank me makes me chuckle, but I’m very proud of that, and she’s not done yet.”

Acquavella’s colleagues agree if she remains in the Navy long enough, she will eventually be only the second woman ever to become chief of the supply corps. And, if not, she might have a Plan B this time. “I think her dream is to be the CEO of Starbucks,” Gebauer said.

Alongside her tours from Baghdad to Pearl Harbor, Acquavella has always cherished her Chapel Hill roots. In the opening sentence of her Navy bio, she celebrates her ties to the UNC women’s soccer dynasty. She and Wendy plan to settle in Hawaii but will continue to visit Chapel Hill regularly as their mainland retreat.

“When I try to explain how amazing it is what Kristin’s become, I get overwhelmed sometimes just talking about it,” Carter said. “There are only a few women in the world who have achieved what she has, but she has never changed. Back in college I called her Floss for no particular reason, and she’s still Floss to me, just with a lot of medals on her chest.”

Forty years since Acquavella left Gaeta, she is still playing with, and beating, the boys. She is one of only 22 active-duty female Navy admirals. “That doesn’t mean much to me because I have an athlete’s mentality, and I’ve always competed, but who I compete with is irrelevant,” Acquavella said. “But perhaps it means something to female officers out there today who have a role model, someone senior to them that maybe they didn’t have before.”

During her extraordinary journey from captain to admiral, Kristin Acquavella has always remained grounded, whether the letters on her uniform read UNC or USN. “It actually takes me back to when I was a little girl receiving flowers before a soccer game in Italy and wondering, ‘Why?’ ” Acquavella said. “Other people see you differently than you see yourself.”

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.