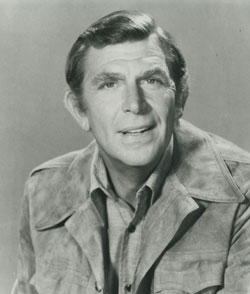

Andy Griffith, Favorite Son of All Tar Heels, Dies at 86

Posted on July 3, 2012

Andy Griffith ’49

Andy Griffith ’49, one of North Carolina’s most famous sons, has died at his home in Manteo. Griffith was best known for his portrayal of a down-home country sheriff with an unmistakable Southern drawl on The Andy Griffith Show and as Ben Matlock, the curmudgeonly criminal defense lawyer who always wore the same suit, on the hit show, Matlock. He was 86.

Former UNC System President Bill Friday ’48 (LLB), a close friend of Griffith, confirmed to media outlets that Griffith died Tuesday morning. It was later reported that his death certificate stated that Griffith had died of a heart attack.

Griffith’s stints on the shows spanned a total of 17 years. The Andy Griffith Show still enjoys tremendous popularity, especially among North Carolinians. His portrayal of Sheriff Andy Taylor was a switch back to simpler times, times that didn’t involve the embroiling politics of the 1960s.

In an archived article from The News & Observer, one fan likened the CBS series to “a tranquilizer or a before-dinner drink — a time to unwind from office pressures before starting in on those evening activities most working wives/mothers engage in,” and another applauded Griffith as “a national treasure.”

Andy Samuel Griffith was born on June 1, 1926, in Mount Airy. He was the only son to Carl Lee Griffith, a carpenter, and Geneva Nunn Griffith, who married shortly after World War I.

Growing up in Mount Airy offered few opportunities, and it was there that he decided to attend college at UNC. He was the first in his family to pursue higher education.

Griffith entered Carolina in 1944, intending to become a Moravian minister, but his passion lay in the dramatic arts, and he switched his major to music. While television transformed him into a household name, it was at UNC that the roots of his inveterate career were planted. He starred in several Playmaker’s productions, including The Gondoliers and The Mikado, laying the foundation for his eventual calling to Broadway. He was also a member of the Phi Mu Alpha music fraternity.

In 1994, he wrote the alumni association with a request: “When I was preparing to attend the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill back in the 1940’s a teacher of mine in Mt. Airy told me I should say my name was ‘Andrew’ because it sounded a lot more important than ‘Andy.’ I respected this man and figured I needed all the help I could get so I went along with it. However, my legal name has always been Andy Samuel Griffith. Any help you can give me in correcting the records at the University will be appreciated.”

While at Chapel Hill, Griffith met and fell in love with Barbara Edwards, who also was an actor who majored in music with a concentration in voice. They wed in 1949 and later adopted two children, Sam and Dixie. Griffith and Edwards separated in October 1971, and in June of the following year they divorced. Later, he married Solica Cassuto in 1975, a Greek actress, but their marriage ended after six years. In 1983, Griffith married Cindy Knight, an actress he met while seeing The Lost Colony play in Manteo. It wasn’t all honeymoon for the couple in the beginning. Two months after they took their vows, Griffith was struck with a neurological disorder that left him partially paralyzed but recovered within a year.

After graduating from the University in 1949, he taught high school music in Goldsboro for three years, at the same time continuing to perform onstage. Griffith appeared as Sir Walter Raleigh in The Lost Colony on Roanoke Island from 1949 to 1953, alongside his wife, who played Eleanor Dare. Together they traveled across the state, performing comedy and singing routines.

But Griffith’s most memorable act was a humorous monologue about a country boy’s first football game. Chapel Hill publisher Orville Campbell ’42, after hearing Griffith perform at The Carolina Inn, convinced Griffith to do something with his country boy monologue “Romeo and Juliet” and his fantasy of a country preacher who stumbles on a football game in Kenan Stadium. Griffith cut a record and “What It Was Was Football,” which he performed at Kenan Stadium, thrust him into the national spotlight when it sold more than 800,000 copies.

The monologue’s success introduced Griffith to the world of showbiz, but it was his role in a television production of No Time for Sergeants that left an imprint on the public’s heart. He went on to perform in the Broadway and film version of the show, bringing him celebrity. Griffith earned a Tony nomination in 1955. It was during his Broadway performances that he first worked with Don Knotts, later to become Barney Fife, Sheriff Taylor’s bumbling, comedic sidekick.

Continuing to pursue film acting, he played Lonesome Rhodes in the 1957 movie A Face in the Crowd a role that established him as a dramatic actor. In 1981, he was nominated for an Emmy for his work in Murder in Texas, a story about a doctor who murders his socially prominent wife.

Most in Hollywood enjoy their 15 minutes of fame, but for Andy Griffith, his 15 minutes turned into movies, television shows, and lucrative contracts. He had struck gold — twice — with the nine-year-long Matlock series. On the show, audiences could still see traces of the Southerner they had grown so comfortable with. Ben Matlock was a mix of Southern affability, instinct and wit, characteristics not unbefitting Griffith.

His ascendancy lasted well into his later years. At age 70, he recorded a collection of popular spirituals titled I Love to Tell the Story. Griffith won a Grammy in 1996 for his album, bringing his career full circle to his first love — music.

In 2005, Griffith was among the first recipients of the inaugural Carolina Performing Arts Lifetime Achievement Awards, with Richard Adler ’43 and Maxine Swalin. In feature coverage of the event, the Review reported about Griffith’s years at Carolina:

When it wasn’t his turn to be on stage, he would lie on the benches that comprised the seating in Memorial Hall before the 1950s, stare up at the big chandelier and listen to the music. Gilbert and Sullivan, Brahms and Mozart, the B Minor Mass. But most of the time he was singing.

“Ah, boy, what a good time,” Griffith said. He was one of those Carolina students for whom the four years truly were spellbinding, from the day as a homesick freshman he sat in Steele dorm and listened to boys harmonizing out in the quad, too shy to join them, to the day he barely graduated but with no questions left about his life’s calling.

Griffith had left home unprepared for college, clinging to the “furniture factory mentality” — an assumption that no matter what, he’d end up back close to the nest, working where his father always had. He said a mentor warned him they’d eat him up in Chapel Hill, “and they nearly did.”

One day he saw a poster for Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Gondoliers. He figured he might make the chorus. Soon after auditions, he saw his name beside a role.

Hill Hall drew him like a magnet, he remembered. He played the trombone and the E-flat Sousaphone, joined the Glee Club and became its president. Five of the eight bucks a week he got for busing tables at Swain Hall went to tuition, so the voice teacher offered him free lessons if he would manage the club’s sheet music.

In August 1944, he sent his parents a picture postcard of Memorial Hall, noting “There’s a building I pass by every day.” In that autumn he was on its stage, the first real one he’d ever been on.

Three of the four standing ovations Griffith took in as many days in September 2005 were on Memorial’s stage. On the occasion of its arts gala, the University probably couldn’t have invented a show business icon with whom the locals were as comfortable, as delighted. The dignitaries spoke of the goodness of song and dance to the soul; Griffith personified it.

He previously established the Andy and Cindi Griffith Scholarship in the departments of dramatic art and music, and he came to Chapel Hill this time to donate his personal archives to the Southern Historical Collection. “This is where I want it all to be,” he said. “I won’t say ‘rest.’ I want it to be used.”

In 1978, Griffith narrated the GAA’s first slide show, “Hark the Sound,” which won a CASE Grand Gold award and continues to be shown during every Spring Reunion gathering.

— David E. Brown ’75 and Faith Ray ’03

More online…

- Fanfare for the Uncommon: Carolina has dressed up Memorial Hall as its ambassador for a daring performing arts venture. Andy Griffith ’49, Richard Adler ’43 and Maxine Swalin are the first recipients of the inaugural Carolina Performing Arts Lifetime Achievement Awards. From the November/December 2005 issue of the Carolina Alumni Review, available online to Carolina Alumni members.