Farewell to an Icon

Time and again, former Chancellor William B. Aycock ’37 defined duty — for himself, for the University, and for the people who sometimes questioned whether Carolina fell on the right side of history. No one was better suited to the task.

by Beth McNichol ’95

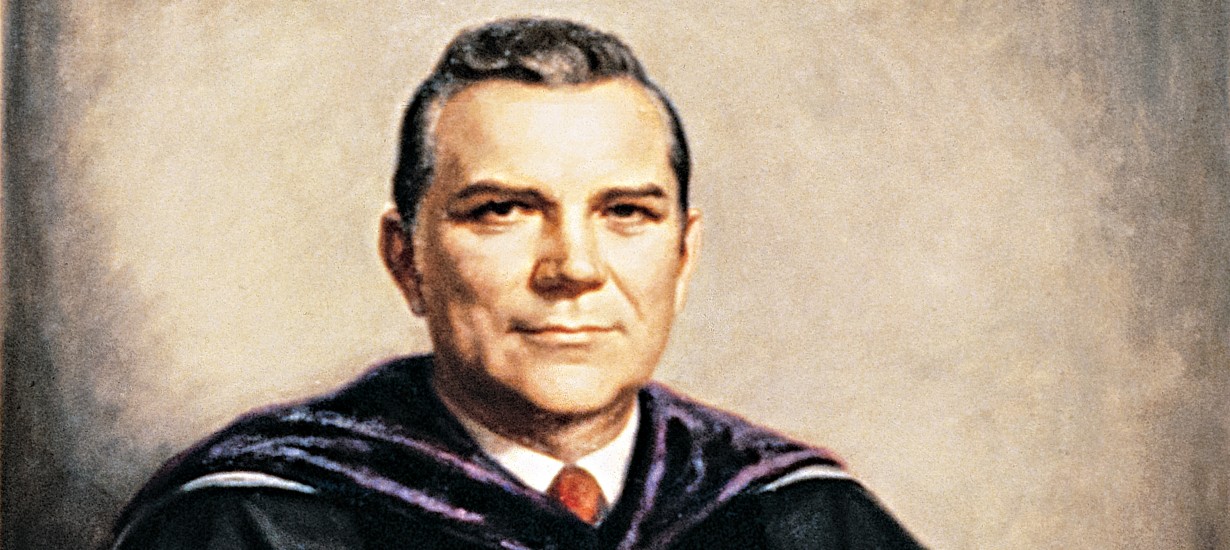

William Brantley Aycock ’37 (MA, ’48 JD), who began his career as a high school history teacher and became a distinguished professor and chancellor of the University during a period of tremendous growth and social and political upheaval, died June 20 in Chapel Hill. He was 99.

Throughout his long life, Aycock walked outside his door and met the face of duty on the other side, where it requested his singular intellect and matchless industry. In each of those moments — when his father fell ill in 1938, requiring him to provide for his family; when World War II erupted, prompting Col. Aycock’s decorated military service; and when the new UNC System president, William Friday ’48 (LLB), asked him to leave the law school to serve as chancellor in 1957 — Aycock never slighted those who needed him.

“I’ll be happy to take a turn,” he told Friday of the chancellorship, vowing not to serve more than seven years. “I’m primarily interested in teaching school, but I’ll come and take a turn.”

Aycock served 36 years at the University, 29 of them in the law school, where he won the McCall Teaching Award five times.

He was back at the law school in early June to attend the announcement that Martin H. Brinkley ’92 (JD) would be the school’s new dean.

His turn as chancellor, from 1957 to 1964, established Aycock as a strategic guardian and often fiery champion of the University’s freedom and integrity at a time when threats to those underpinnings abounded.

He struck back with fervor, and not without political risk, at the Speaker Ban Law, which was enacted covertly and without debate by the N.C. General Assembly in 1963 to block Communist speakers from the campus.

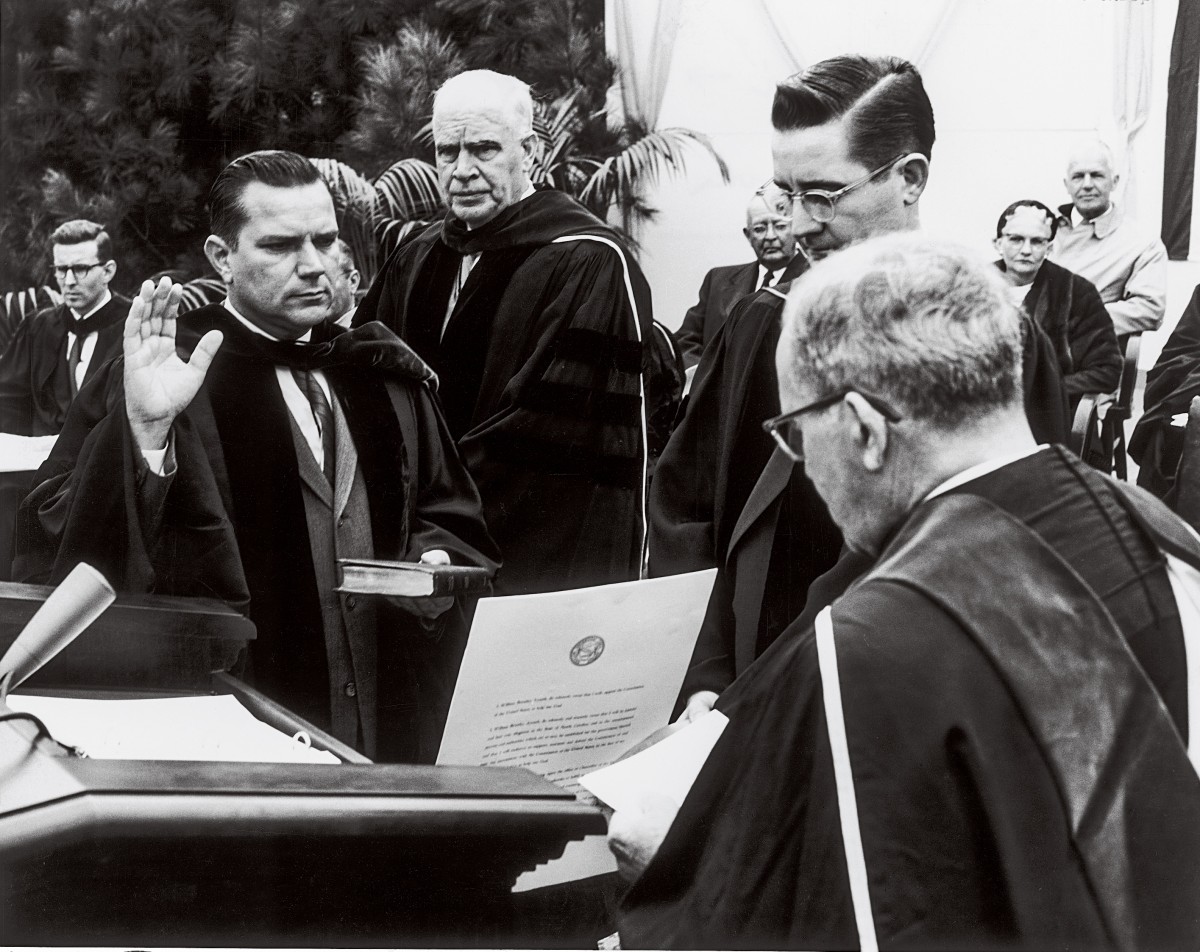

Aycock is sworn in as chancellor in 1957 by North Carolina Chief Justice J. Wallace Winborne (class of 1906), with Luther H. Hodges Sr. (class of 1919) and William Friday ’48 (LLB) attending. Aycock’s legacy is indelibly tied to the often-noisy campaign to rid UNC and other universities of the Speaker Ban Law, portrayed below in the famous photo of banned speakers addressing students and others from across the campus border wall. (GAA file photo)

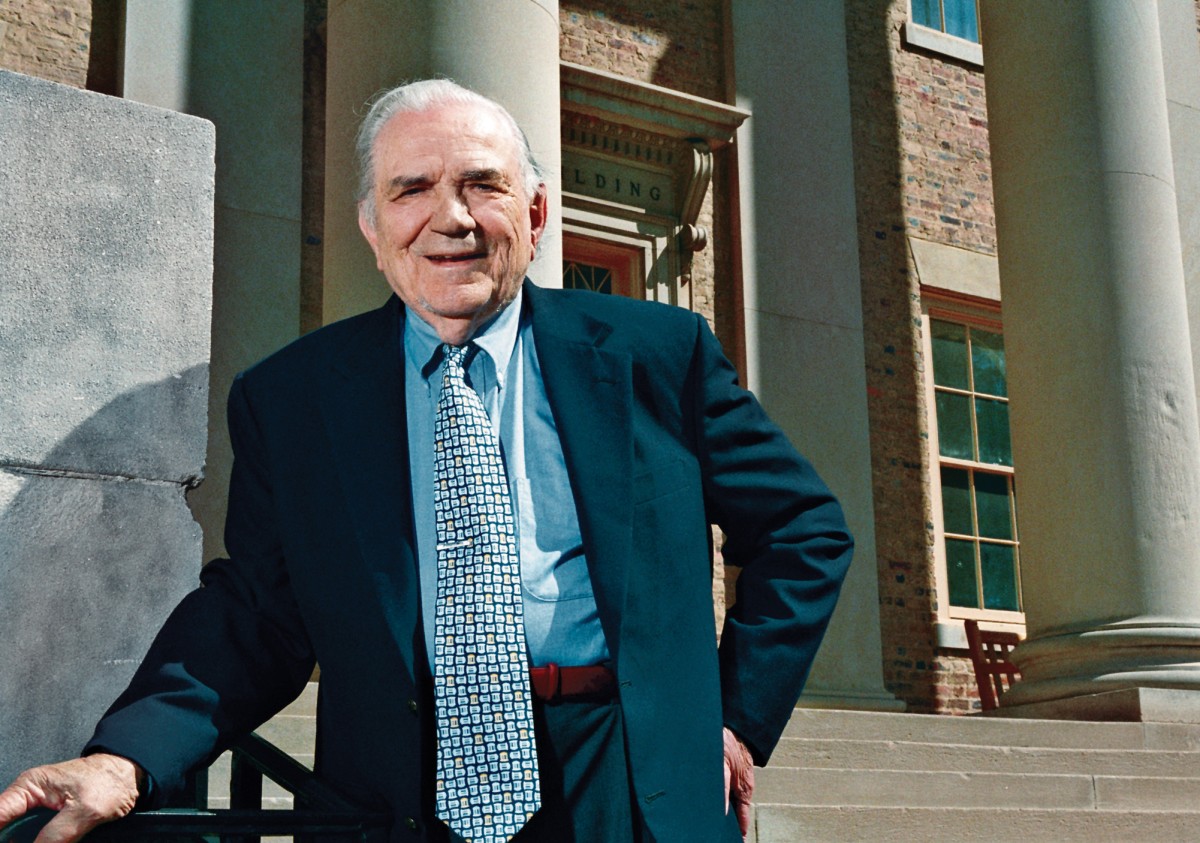

(Photo by Jock Lauterer ’67)

Aycock vs. Speaker Ban Law

Aycock, who had made protecting the campus’s freedom a priority of his installation address six years earlier, educated the University’s trustees and its alumni on the law’s affront to Carolina’s reputation through a series of speeches in which he broke down the hypocrisy of its passage. In a blistering reprimand of the legislation before the Greensboro Bar Association in 1963, Aycock took its creators in Raleigh to task, calling it an “insult,” the “sloppiest” and “the poorest-drafted legislation I have ever seen. … This law is so full of ambiguities that even the author couldn’t possibly say what it really means.”

Though four years would pass before the law would be overturned, it was Aycock’s nimble legal mind and point-by-point dismissal of the Speaker Ban Law as unenforceable and dangerous that formed the foundation of the lawsuit that ultimately destroyed it.

Explaining his hiring of Aycock, Friday once said: “The University had to have a leader who could engineer the decisive changes about to take place, to do it with a sense of grace, to do it with a sense of respect, but also in the full realization that the University was turning itself dramatically. It was entering the post-World War era of internationalism, a new day in race relations, a new day in the role the University plays in the life of a state.”

“I told Bill Friday that as a faculty member I had frequently suggested that there ought to be a way that teachers could be induced to taking a turn in administration,” Aycock told North Carolina Lawyer magazine in 2014. “There were so many departments — 14 schools and colleges. They had passed a very nice arrangement where they picked some of the very best teachers to be department heads, and after four years they could continue or go back to teaching. If it came back to me, I would say the same rules would apply to the chancellor. I intended to be known as a teacher, not as [an] administrator, so after I took a term as chancellor, I wanted to go back to teaching, and I did. … It was good for the university and good for me.”

When his tenure as chancellor ended, Aycock closed the door at South Building and walked straight back to the law school to prepare for his return to teaching a full course load. He worked feverishly over the next seven days to learn all that had changed in the law over the previous seven years — so feverishly, in fact, that he suffered a bleeding ulcer later that academic year while spending a Saturday at work in the school.

“I had a big vacation, from the time it took me to walk from South Building to Manning Hall, which is about 10 minutes,” Aycock said of his transition period from administration to teaching, which he called the “hardest work I’ve ever done.”

As chancellor he also marshaled a campus that was often under funding fire from the Legislature through a new era of expansion, both in buildings and in a baby-boom-infused student body, which saw an average increase of 500 students each year.

In the late 1950s, he faced an atmosphere in Raleigh that was skeptical that the work of professors was worthy of UNC’s ever-higher budget requests.

He told the Legislature’s joint appropriations committee: “True, if our requests are rejected, we shall continue to have the visible symbols of a University. We are deeply concerned for what may happen to those things which are not readily discernible but which nevertheless provide the fundamental qualities of a University. Unlike erosion of the Outer Banks, erosion of the quality of a university is difficult to detect.”

Aycock speaks on University Day in 1961, with UNC System President William Friday and President John F. Kennedy looking on. (Photo by Hugh Morton ’43/Hugh Morton Collection)

‘The integrity of the institution was involved’

He also tended the early weeds that sprouted from the increasingly lush fields of intercollegiate athletics. While the basketball team already faced NCAA punishment for recruiting violations, Aycock suspended a star player, All-American Doug Moe ’61, in 1961 for taking $75 from a gambler involved in point shaving at the Dixie Classic; although Moe refused to throw games, he had been dishonest about the affair when questioned by Aycock.

The chancellor was awakened one night by student protests surrounding the suspension. The student government previously had declared Moe not guilty, citing its inability to try another player who had drawn him into the scandal and was no longer enrolled. Aycock opened Gerrard Hall in the darkness and held a packed town hall-style meeting with the protesters to explain his actions.

“I went on to say … that the integrity of the institution was involved, and it simply was not something that could be dealt with on the basis of any kind of a technicality,” Aycock recalled. “And that I had done it, and I would do it again under the same circumstances. And I was pleased that when I left a couple of hours later, I was given a standing ovation.”

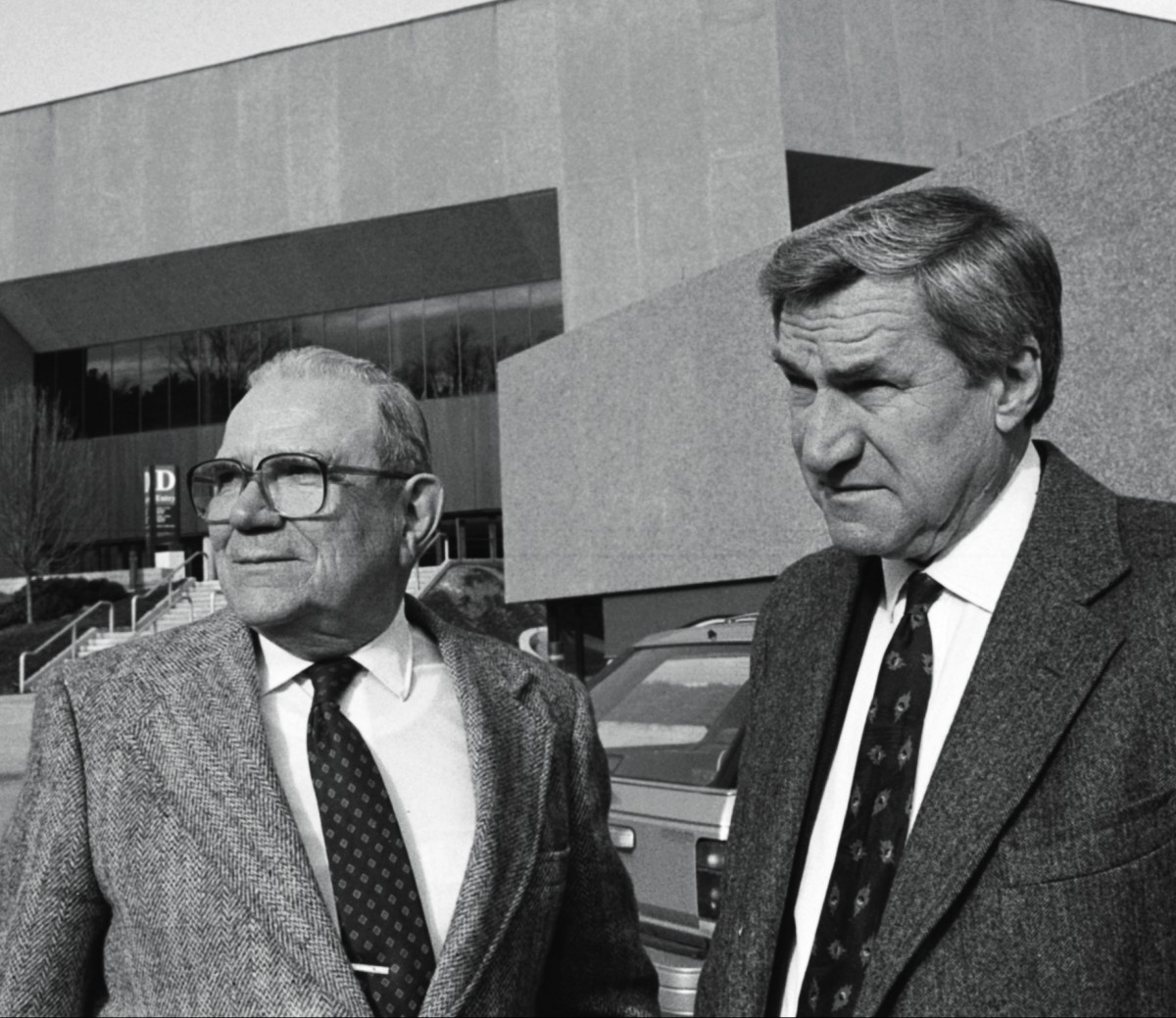

The scandals led to several reforms, including barring players from participating in summer leagues. To right the ship after forcing coach Frank McGuire’s resignation, Aycock elevated to head coach a young assistant named Dean Smith. Aycock primarily was impressed with Smith’s integrity off the court, but 879 wins and 36 years later, the Kansan’s brilliant technical mind on the court proved to be a gargantuan bonus.

Aycock sized up Dean Smith — not so much as a coach but as a person — then hired him quickly and with no fanfare, afraid that Frank McGuire might take Smith away from Chapel Hill. The two remained lifelong close friends. (Photo by Hugh Morton ’43/Hugh Morton Collection)

Aycock recalled his hiring of Smith for North Carolina Lawyer: “We got in a little trouble with the NCAA, and it turned out Frank McGuire said he didn’t do any of the things they had in there. And I said for your sake and for the university we have to get together a defense. And he said, ‘Let Dean Smith handle it.’ So that is where I got to know him personally. To make a long story short, on one trip I took him with me to California. I learned about him as a person. I knew when Frank McGuire hired him he could have hired any young coach in the country because he had just won the national championship undefeated. I knew he knew X’s and O’s, no question about that. He worked with me and I found out he was the sort of fellow I got along with real well. His mother and daddy were both school teachers. …

“Later on we got word that Frank McGuire was dickering with the pros. He was dickering with the Philadelphia Warriors, as they called them in those days. He finally decided to go, and came to my office and said, ‘I have come to resign. I am going to the Philadelphia Warriors.’ He got to the door and I said to myself, ‘Lord have mercy, I hope he is not going to take Dean Smith.’ I had already made up my mind; I had heard the rumors. I asked Frank McGuire if he knew where he was and McGuire said he’s right out there in my car. And I said send him in.

“I never even let him sit down. I stood up to meet him. I said, Dean, do you want this job as head coach, and he said yes, and I said well, you’re it. Goodbye. The next day I announced it. We didn’t get into any paperwork, no dickering, no search committee. And not a single person said that’s a good appointment. I figured I knew more about him than anybody, so why should we spend hundreds of thousands of dollars bringing people in?”

A generation’s challenge and legacy

Aycock’s almost compulsive dedication to the tasks at hand was born of his witness to time lost and dreams deferred — his and others. He was of a generation bound by circumstance and forged from obligation to serve country, support family and then build communities from the ashes of economic gloom and world war. He was, like many of his peers, a man who became serious early in life and remained indefatigable to greater purpose throughout.

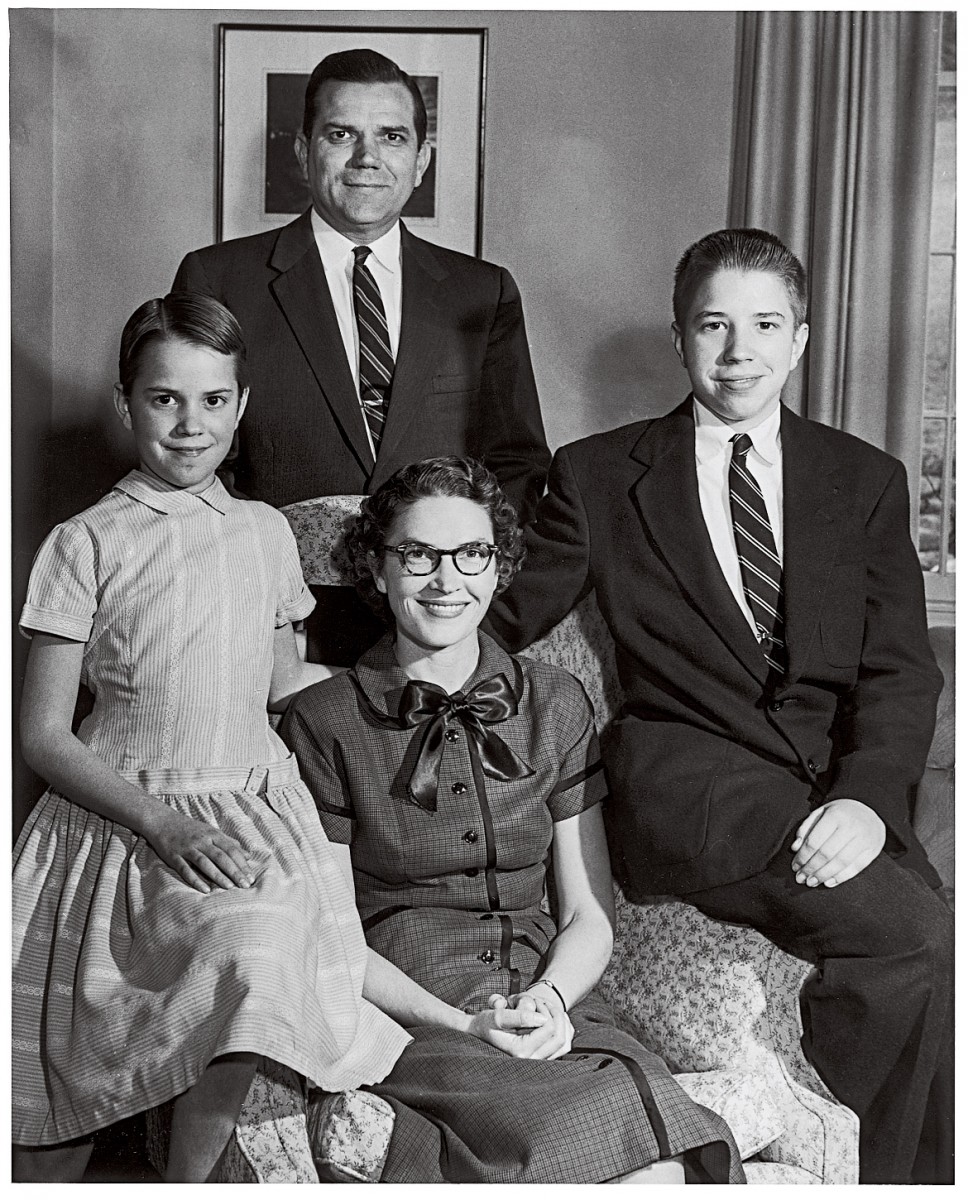

A Carolina family: Aycock with his wife, Grace ’69 (MSW), daughter Nancy ’69 (’98 MSW) and son Bill ’65 (’70 JD). (GAA file photo)

He was born in Lucama, in Wilson County, in 1915, and raised in Selma with two sisters, where his father was a farmer and a merchant who waited half his life for the chance to go to law school. But William Preston Aycock never wasted a moment in teaching his son. In the years in which the elder Aycock became a lawyer, mayor and Johnston County judge, he and 12-year-old son Bill started a dairy business together. Twice a day, 365 days a year until Bill left for college, he and his father milked four to six cows and sold their product at pennies per gallon.

No money was made from the venture; but, as the younger Aycock noted, that had never been the intention.

“He was very busy at the law,” Aycock recalled of his father in 1990, “often working at night also, but he envisioned the dairy business as a means whereby we could spend time together. We would talk about things in a very casual manner; he would bring up controversial subjects and he would not … tell me what to do or what not to do. We were just sitting there, milking cows, talking about the pros and cons, and he left it up to me. This very delicate instruction he gave and the exercise of judgment, it stood me in good stead.”

Years later, those fatherly moments would echo in Aycock’s response to a friend, who asked him if he was bothered by his children and their friends cavorting upon his fastidiously tended lawn in front of the home he helped build on Arrowhead Road. “I’m raising children now,” Aycock told him. “I’ll raise grass later.”

Aycock spent youthful hours hanging around the judicial system with his father (“You saw dramas unfold in the courthouse, which were better than some that were put on the stage,” Aycock remarked), and he envisioned joining forces in a father-son law practice one day.

The war years

But the sudden failing health of his father following a heart attack intervened. Aycock took the education degree he had earned at N.C. State in 1936 — where he was student body president — and the master’s degree in history he had muscled through with uncommon speed at Carolina in 1937, and instead went to work at the future Grimsley High School in Greensboro to support his sisters through college. Later he worked at the National Youth Administration in Raleigh, where he met Grace Mewborn ’69 (MSW). They married in October 1941.

Aycock’s ROTC photo from N.C. State (Courtesy of Special Collections, NCSU)

The Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in December, and Aycock, who had earned an ROTC commission at State, gave four more years to duty’s knock. He trained a segregated battalion of Japanese-American soldiers for combat in Italy and then served in Gen. George S. Patton’s Third Army at the end of the Battle of the Bulge in Germany in 1945, earning a Silver Star, a Bronze Star and the Legion of Merit.

For eight years, he had longed to enter law school, just as his father had bided his time decades earlier. When Aycock was finally mustered out of the Army in 1946, he would wait no more. He drove through the night from Camp Shelby in Mississippi to Chapel Hill, where he strode into the law school on a Saturday morning and asked Dean Robert Wettach to admit him.

The fact that he went home that very night and began studying tort law with a textbook borrowed from Wettach would come as no surprise to his classmates, who were awestruck by his intellectual prowess. J. Dickson Phillips ’48 (JD), a retired U.S. appeals court judge who was a member of Aycock’s uncommonly competent study group (which included Bill Friday and other future leaders), recalled that whenever professors got “a little flustered in class if pushed too hard” for answers they did not readily possess, they would turn to Aycock.

‘The only person … who had it figured out’

Aycock on campus in 2005. “Some straight arrows,” his close friend Dickson Phillips ’48 (JD) remarked in 2007, “are insufferable. He was a lovable one.” Aycock kept a sharp mind into his 100th year, often putting campus affairs in context for visitors. (Photo by Dan Sears ’74)

“Aycock wasn’t being enlisted to impart knowledge that he shared with the professor,” Phillips said in 2007. “He was the only person in the room who had it figured out.”

On another occasion, Professor Herbert Baer lost his voice and asked Aycock to teach his class for six weeks until he healed. The experiment went so well that Wettach offered Aycock an assistant professorship many months before he had received his degree. He graduated first in his class in February 1948 and started teaching the following week.

“He emerged from the pack of considerable talent in our class as the clear academic frontrunner,” Phillips said. “Emerge is not quite the word; he effectively went off and left the pack. He simply operated on a different level from the rest of us.”

In 1951, Aycock served as special assistant to Frank Porter Graham (class of 1909) on the United Nations mission to India and Pakistan in the Kashmir dispute. Aycock was named Kenan Professor of law in 1966.

Aycock was an honorary member of Phi Beta Kappa and a member of the Order of the Golden Fleece. He received the Thomas Jefferson Award from UNC, the Distinguished Alumnus Award and Lifetime Achievement Award from the UNC Law Alumni Association, the William R. Davie Award from the Board of Trustees, the Distinguished Service Medal from the GAA, the University Award from the UNC System Board of Governors, and the Liberty Bell Award from the N.C. Bar Association. In 1990, the University dedicated the William B. Aycock Family Medicine Center in his honor; and in 1998, the School of Medicine created the William B. Aycock Distinguished Professor of family medicine position.

As chancellor he would often steal away for a soda at the Campus Y and talk with passersby, taking the daily heartbeat of his campus; or pop in on the Tar Heels at the baseball diamond.

One day, he was told by a security officer about a group of adults and children who had undertaken a small civil rights march on campus. The officer had told the group that they couldn’t march.

“Well,” Aycock responded, “you’ll have to go back and tell them that they can. And make a request to them that, because young children are involved, that if they would march on the sidewalk, rather than on busy Cameron Avenue, it would be better from a safety standpoint.”

“Some straight arrows,” Dickson Phillips remarked in 2007, “are insufferable. [Aycock] was a lovable one.”

Gathering his brawny intellect and sound judgment — learned in the courthouse and on the dairy farm and honed across the peaks and valleys of his life — Aycock time and again defined duty, for himself, for the University, and for the people who sometimes questioned whether Carolina fell on the right side of history.

No one was better suited to the task.

“To engage in his diverse pursuits, even at a level of mediocrity barely above disastrous, would require considerable versatility,” former law school dean Henry Brandis ’28 said in 2007. “To engage in them at Aycock’s consistently high level of competence requires versatility with a solid touch of genius. The great ones are fashioned in unique molds; and William Brantley Aycock is one of the greatest.”

Beth McNichol ’95, a freelance writer based in Raleigh, is a former associate editor for the Review.

More about Chancellor Aycock can be found at these links:

-

Grit and Freedom: The Legacy of William B. Aycock ’37 — Part of the Carolina Alumni Review’s “History of the Chancellorship” series, with this coverage appearing in the January/February 1996 issue.

-

With No Warning, No Debate: The state’s legislators didn’t dare oppose the Speaker Ban Law that was dropped on UNC in 1963. But the chancellor did not feel so politically hamstrung. From the July/August 2005 Carolina Alumni Review.

-

Before the Students, Aycock Went to the Wall for UNC: From the July/August 2005 Carolina Alumni Review.

-

‘I’ll Take My Turn’ — “Yours at Carolina” column by GAA President Doug Dibbert ’70 from July/August 2012 issue of the Review.

-

Aycock Elected Chancellor: From the January 1957 Alumni Review.

Chancellor Aycock’s Speaker Ban speeches:

-

The Speaker Ban Law

To the UNC Board of Trustees

Oct. 28, 1963

-

The Law and University

To the Greensboro Bar Association

Nov. 21, 1963

-

Laws Affecting Speaking

To the Watauga Club, Raleigh

Jan. 21, 1964

-

Statement in Opposition to the Speaker Ban Law

To the Speaker Ban Law Study Commission

Sept. 8, 1965

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.