From the Sublime to the Horrific

Berkley Hudson ’03 (PhD) was obsessed with preserving decades-old photographs that uncovered the truth about his hometown. Now they’re part of UNC’s Southern Historical Collection.

by Janine Latus

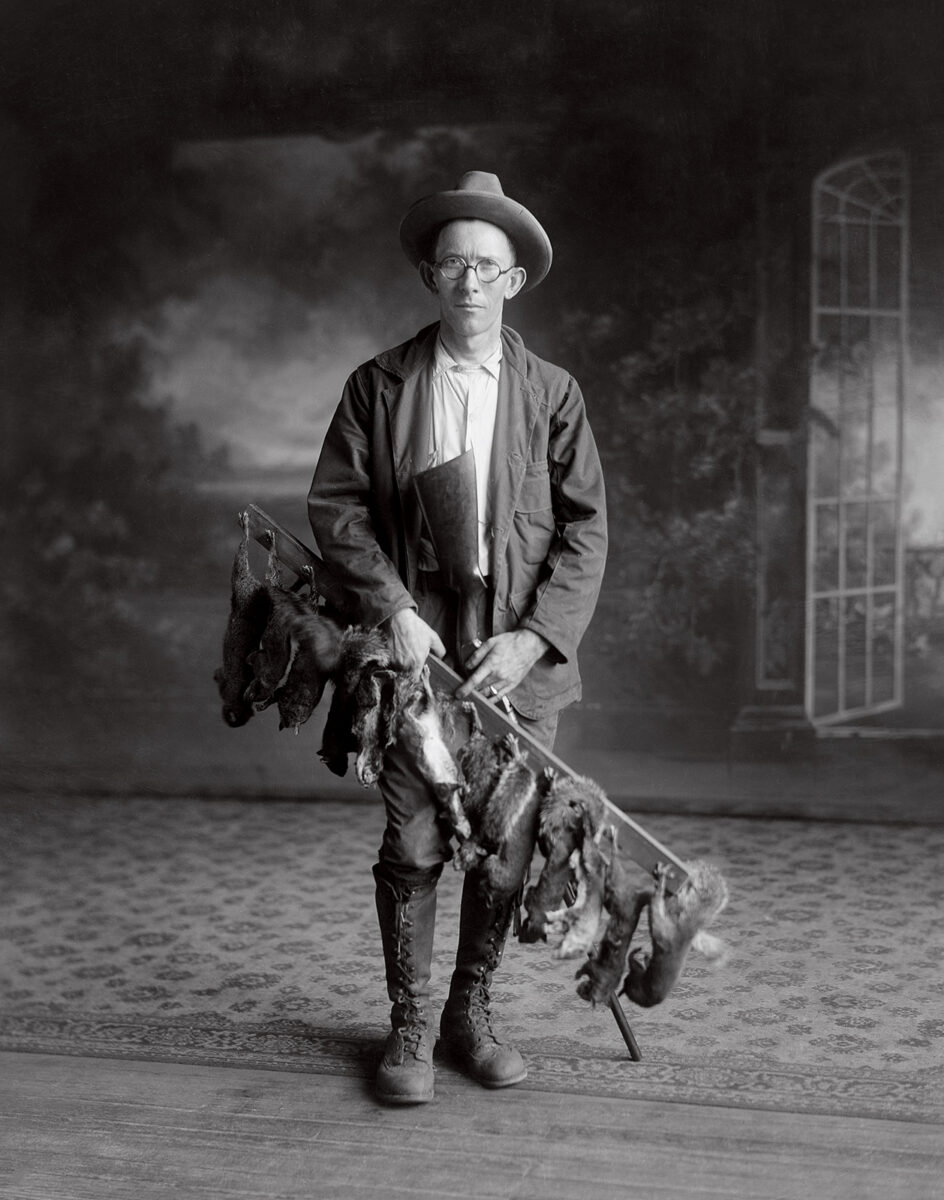

Studio portrait of O.N. Pruitt with 12-gauge shotgun and squirrels, circa 1925. Photo courtesy of UNC Libraries

This is a story of two obsessed men.

One — Otis Noel Pruitt — was addicted to photography, lugging his large-format cameras around the small town of Columbus, Mississippi, from about 1920 to 1960, documenting the joys and terrors that occurred side by side in the Jim Crow South. Pruitt, slender with a receding hairline and big ears, saw the world through the privileged eyes of a white man of that era, yet he posed Black and white people in the same wicker peacock chair, giving each person dignity before the lens. He took photos on the street and in the fields, in front of the town’s largest white-owned car dealership and in Catfish Alley, its hub of Black-owned businesses. He captured portraits, pageants and parades, but also lynchings and public executions, a Ku Klux Klan rally on Main Street and Black tornado victims laid out in a makeshift morgue in the hot sun.

The second man — Berkley Hudson ’03 (PhD) — was obsessed with preserving and publishing Pruitt’s photographs, using them to uncover the truth about his hometown. Hudson, who grew up in Columbus, was a toddler on his mother’s lap in 1953 when Pruitt ducked under his black cloth and made a portrait of Hudson’s extended family. It hung for years among an array of photos in Hudson’s childhood home.

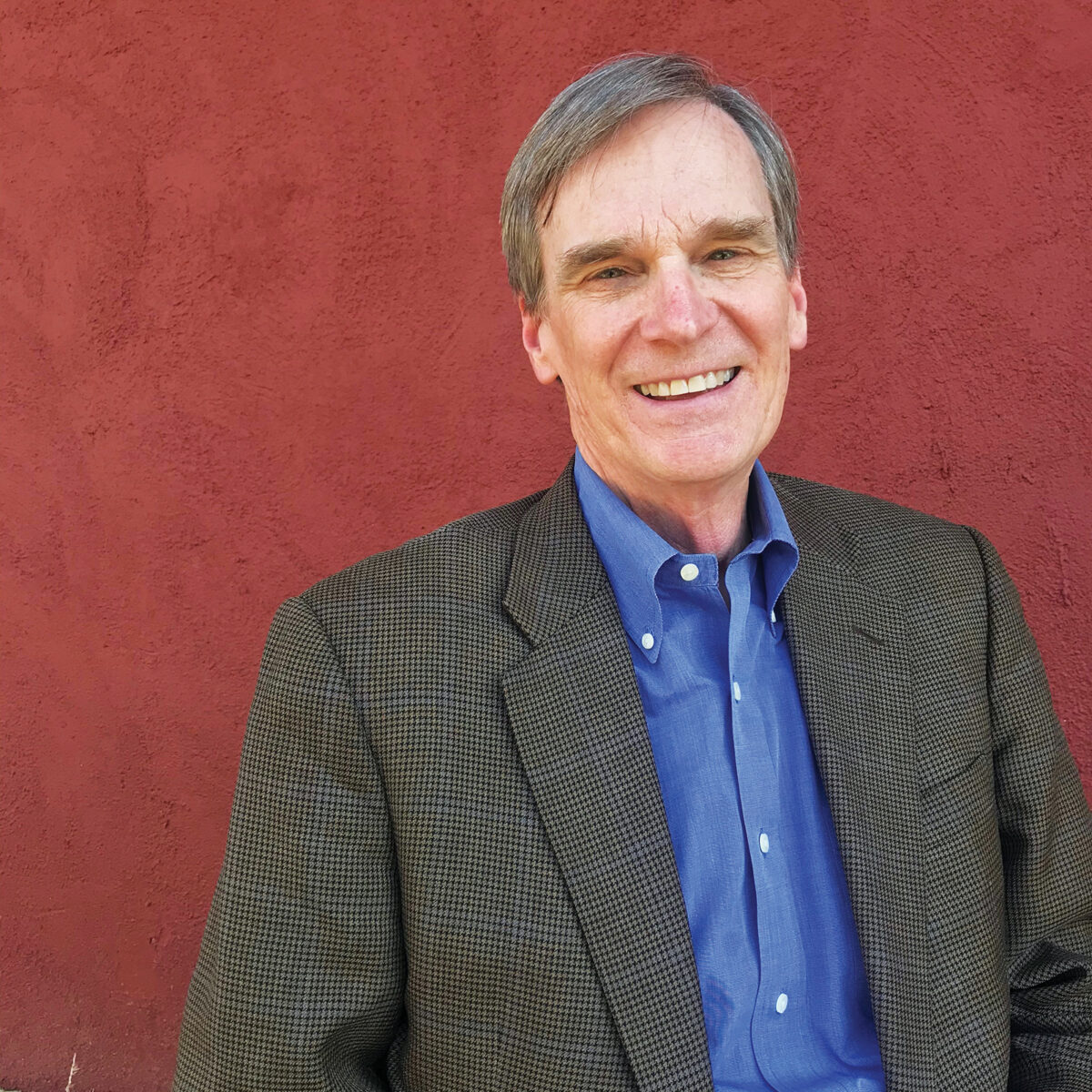

Hudson, now 70, father of two and runner of more than a dozen marathons, was a lanky 20-something studying journalism at Columbia University in New York in the mid-1970s when he followed two boyhood friends up the creaky stairs of the red-brick building at 413-½ Main Street during a visit home. One of them, Mark Gooch, had been working on an oral history of Catfish Alley and had heard the town’s de facto photographer had left behind thousands of negatives, decomposing and emitting an eye-watering vinegar stench. The content of the images, too, left Hudson reeling. It showed him a side of his town he had never known. That’s when the obsession began.

“We could see — driven by our own curiosity and love, hate and confusion about our experiences growing up here — that this was connected to us,” Hudson said. “We wanted to preserve these images that seemed to be telling untold stories about our town.”

Berkley Hudson ’03 (PhD) said parents, friends and teachers couldn’t explain the racial turmoil, but the writers and journalists did, “and that’s what made me want to be a journalist.” Photo by Tom Rankin ’84 (MA)

What Hudson and his friends, Gooch and Birney Imes, both professional photographers, didn’t realize was that it would take them and later two other friends 30 years of relentless determination to preserve and curate a photobiography of their hometown of Columbus, called Possum Town by the locals. The Possum Boys, as they called themselves, eventually found the photos a home at Carolina’s Wilson Library as part of the Southern Historical Collection.

About 190 of the photos appear in Mr. Pruitt’s Possum Town: Trouble and Resilience in the American South, published in January by the University of North Carolina Press in partnership with the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University. An accompanying traveling exhibit, sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities, opened in Columbus in February.

“This is a story about a white photographer working in a racially segregated time in the American South who unflinchingly recorded a kaleidoscopic range of life in a community that reflects the life of our country at that time,” said Hudson, Possum Town’s author. “That’s what I wanted to show in the book and exhibit, this range that includes the sublime, the sacred, the tragic, the shocking, the horrific and the uplifting.”

Photography addict

O.N. Pruitt was born on a farm in southern Mississippi in 1891. By 19 he was married, and, just as today’s parents do with their cell phones, he obsessively snapped pictures of his children with his bulky Kodak Brownie 122, its accordion-style lens unfolding from a leather-covered box. In his early 20s, while working in his uncle’s mercantile store, he developed a side hustle taking his Brownie into the surrounding countryside to photograph timberland to show out-of-state lumber companies.

Pruitt’s uncle quickly tired of the acidic stench of the chemicals in the makeshift darkroom Pruitt had set up in the stockroom. By 1915 Pruitt had left the store and become a full-time photographer. He traveled 500 miles north to spend a year at the Illinois College of Photography, then returned to Mississippi, eventually buying out Columbus’ existing photographer, Henry Hoffmeister.

“He was a photography addict,” Hudson said. Thomas Caldwell, Pruitt’s grandson, told Hudson in a 2001 interview that his grandfather “didn’t care about much of anything other than photography … and going fishing.” Pruitt’s wife, Lena, managed the business.

When the traveling exhibit opened in Columbus in February, a local collector showed Hudson a dog-eared notebook with “Mrs. O.N. Pruitt, MSCW Class ’58” scrawled on the cover. Inside, in Lena Pruitt’s handwriting, are the names and addresses of students in a class photo from the Mississippi State College for Women, the first public women’s college in the country. Pruitt — using one of the large-format cameras designed so that photographers could sell copies to everyone in a group photo — charged $2.50 per print, about $24 in today’s dollars. He sold 72. There is no record of what he charged for other photos, although during the Depression he was known to barter for fish, chickens, eggs and produce.

Pruitt’s studio was on the second floor of one of several red-brick buildings tightly packed together on a newly paved street lined with restaurants and shops. At the top of the hill towered the Lowndes County Courthouse, built before the Civil War, with a gleaming white marble monument to Confederate soldiers that loomed out front. (It was removed last year.) Stately antebellum homes on broad manicured lawns lined the streets nearby.

Pruitt and his assistant and later business partner, Calvin Shanks, posed people for portraits in the front of the studio. In the back, ducking under clotheslines of drying negatives, they developed their film. The portraits show people in their Sunday best, courtly and sometimes dapper. They held still and gave faint smiles, freezing for the full second it took for Pruitt’s shutter to click.

“The thing about studio portraits is that people choose to be photographed,” said Tom Rankin ’84 (MA), professor of the practice of art and documentary studies at Duke University and former director of the school’s Center for Documentary Studies, who spent years as an adviser on the project. “They present themselves to the camera as they see themselves and as they would like to be seen. That’s where the studio image can have such power.”

The respect inherent in Pruitt’s portraits contrasted to photos taken outside the studio, in a town where restroom signs read White Men, White Women and Colored, and theaters and restaurants had segregated seating. “What we see is limited in that you’re seeing Black lives through a white studio photographer,” Rankin said.

Pruitt was not surreptitious. One of his cameras, discovered in Florida, weighed hundreds of pounds, Hudson said. Almost all of them required tripods, due both to their weight and their slow shutter speed. It was obvious Pruitt was a photographer, so people knew their picture was being taken.

“He’s not walking around with a handheld camera and just saying, ‘I’ll take this,’ ” Rankin said. “There’s a lot of intent, a lot of setup. … He’s clearly present. There are no stolen images.”

Hudson and his friends didn’t realize that it would take them 30 years of relentless determination to preserve and curate a photobiography of their hometown of Columbus, called Possum Town by the locals.

Renowned hunting dog breeder and trainer Er M. Shelley, center, with his wife, Lucille, to his left, and three dog trainers, circa 1930. Photo courtesy of UNC Libraries

“A deeply violent place”

Some subjects, however, couldn’t give consent. After the Tupelo tornado of 1936 ripped through Mississippi, Pruitt traveled around to capture not just property damage but the makeshift morgue of Black bodies exposed to the sun. The local sheriff’s office and insurance companies hired Pruitt to document homicides, train and car wrecks, fires and natural disasters. He also captured the aftermath of the 1934 execution of James Keaton, a Black man who had been found guilty by an all-white jury of killing the owner of a service station. The photo, taken on the courthouse lawn, shows 19 white men crammed under a scaffold with Keaton’s body suspended through the gallows’ trap door.

Boy with bloodied nose. Hudson says that Pruitt was determined to document his community, whether that meant shooting baptisms or scenes of violence. Photo courtesy of UNC Libraries

A year later, according to accounts published in newspapers nationwide, the sheriff called Pruitt. Come quickly, he said, according to the account in Possum Town, there’s been a double lynching. “With that, Pruitt, who kept his camera equipment at the ready in his car, sped on paved roads and then gravel ones,” Hudson wrote. “Eight miles south of town, in a churchyard, he found lynched from an oak tree the bodies of two young ‘Negro farmers.’ ”

The two men, Bert Moore and Dooley Morton, had been accused of harassing a white woman. No one was ever charged in their murder. Newspapers reported that hundreds of people came to gawk, and the bodies weren’t cut down for most of a day. In one photo a white man is crouched, clutching the pant legs of the two lynched men so they wouldn’t swing and blur Pruitt’s photo.

More than 4,400 racial-terror lynchings were documented in the United States between 1877 and 1950 by the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit group based in Montgomery, Alabama, that provides legal aid to people who believe they are wrongfully convicted or cannot afford representation. Twenty of the recorded lynchings occurred in Lowndes County.

A few photos of lynchings and executions appear in Possum Town and in the exhibit, selected after long debates among Hudson, civil rights scholars, editors and curators about the ethics of showing photos of intimidation, violence and racism. In the exhibit the sensitive photos are behind a black curtain. A sign warns that the section — called Deadly Divisions — includes depictions of racial violence, including lynching.

“The people who lived through that era wouldn’t be surprised by those pictures,” said William Sturkey, an associate professor of history at Carolina who studies race in the American South. “It’s the truth of what America was — a deeply violent place — and facing that head-on is the right way to reconcile our past. It’s the reality of Black life at the time that this could happen to you or someone you know and love. I don’t think ignoring them does honor to the victims.”

Columbus resident Janice Ellis was drawn to the opening of the exhibition by the enlarged photographs of people — adults and children, Black and white — hanging outside the arts center. But once inside, she became deeply upset when she saw the photos of violence. She called a college friend, Edgar Brady, a pastor at an integrated Methodist church in Ohio, who changed her mind, she said. “If you visit the Holocaust Museum, you need to see what happened to those people,” Ellis said Brady told her. “Black people and white, too, need to see this, and we need to talk about it. It’s an ugly part of history, but it’s the truth.”

Pruitt also documented joy. He took photos of Black and white baptisms, side by side on the banks of the muddy Tombigbee River. Hudson’s mother used to walk down on Sundays to watch as Black and white Baptists were dunked into the coffee-colored water and lifted up, born anew, Hudson said.

“One of the beautiful things about this collection is that it shows a lot of types of interaction across the community, between people of different races and social status,” said Jim Carnes ’77, another boyhood friend who worked with Hudson to preserve Pruitt’s work. “As patronizing or paternalistic or controlling as much of that interaction was, there had to have been some recognition of humanity, which to me just provides the ultimate contrast for the violence.”

“This is a story about a white photographer working in a racially segregated time in the American South who unflinchingly recorded a kaleidoscopic range of life.”

— Berkley Hudson ’03 (PhD)

Untold history

All these photos engrossed Hudson, who grew up in a three-bedroom red-brick house a mile off Main Street. The Hudsons employed a Black maid, Lulu Belle Gardner Dillard, a mother of eight children. She cared for Hudson when his mother was out running errands or attending meetings, including, Hudson said, those of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, an organization dedicated to venerating the memory of the Confederacy. The organization’s N.C. division, along with UNC, erected the Silent Sam Confederate Monument on campus in 1913.

Hudson attended the all-white Stephen D. Lee High School, named for a hometown Confederate general hero and not integrated until Hudson was a junior, 13 years after Brown v. Board of Education made school segregation illegal. In school plays, white students performed in blackface, Hudson wrote in Possum Town. As a Cub Scout, Hudson was tucked into his gray Confederate uniform, replete with gold braid and the stars and bars, so he could play host for pilgrimage tours of antebellum homes. He and his mother walked nearly daily to the library, and he read widely. He was 12 in 1964 when three civil rights workers were killed in Philadelphia, Mississippi, just 87 miles away. His brother was a student at Ole Miss when James Meredith integrated the university and it erupted into riots. He and his family listened to the radio as National Guard troops marched into Oxford to quell the violence. Yet Hudson said he didn’t know until he saw Pruitt’s pictures that there had been lynchings or a KKK rally in his hometown.

“I was a fish swimming in the water of racial segregation, and I was very aware of what that meant,” Hudson said. “There were physical signs everywhere and unstated signs everywhere.”

Hudson drank from the white drinking fountain and entered the Columbus theater through the front door. Black people would call him “Cap’n,” and step aside to let him pass. “My parents, my family friends, my Sunday school teachers, none of them could explain this racial turmoil that was going on all around me,” he said. “The writers and journalists did, and that’s what made me want to be a journalist.”

Hudson left Columbus to attend Samford University in Birmingham in 1969, then transferred to the University of Mississippi in 1970, where he earned his undergraduate degree. He received his master’s degree in journalism in 1974 from Columbia University. As part of his master’s thesis he wrote about tensions between elderly Jewish people living on Coney Island and the Black and Puerto Rican people moving into city housing projects. Hudson said the research made him aware of racial and ethnic tensions beyond what he had experienced in Mississippi.

Hudson returned to Columbus in the mid-’70s to visit, which is when he and his friends trudged up the stairs to Pruitt’s old studio and the boxes of negatives. They belonged then to Pruitt’s partner, Shanks, “a beanpole of a white man with curly brown hair and a cigar often in the side of his mouth,” Hudson wrote. The boyhood friends — Hudson, Imes, Carnes, Mark Gooch and David Gooch, Mark’s brother — offered to buy them, but Shanks planned to make them into calendars. He never got around to it.

“We knew at the outset that this collection was something that deserved a wide audience and had many stories to tell and many questions to pose,” said Carnes, who went on to work for the Southern Poverty Law Center and later directed an Alabama anti-poverty program called Alabama Arise. “It’s a gold mine.”

A career covering injustice

Hudson was immediately thrown into covering injustice as a young reporter at The Providence Journal in Rhode Island, where he wrote about the Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan and reported on KKK members being showered with bottles, eggs and tomatoes while marching in Boston. He wrote about Haitian immigrants and refugees arriving by boat from Cuba, and federal detention camps for people who had fled Iran.

In 1988, Hudson took a reporting job at the Los Angeles Times and wrote about Chinese immigrants who ended up in LA detention facilities and about racial tensions after Rodney King was beaten by police. When he could, Hudson traveled back to Columbus, showing photos from the Pruitt collection to his mother, the town’s librarian and strangers, asking, “Who is this? What’s the story here?”

“It’s fair to say that this project has dragged him around for the better part of 30 years,” said professional storyteller Milbre Burch, Hudson’s wife since 1986. “There have been very few years when Pruitt wasn’t part of our life.”

When Shanks died, the photos were sold to Bill Frates, a photographic hobbyist who admired Pruitt’s photos of trains, Hudson wrote. Frates kept the collection in his Main Street general store alongside refrigerators, stoves, shotguns, fishing rods and knitting supplies. The photos and negatives still emitted a stench. In 1987, Frates agreed to sell Hudson and his friends what turned out to be 142,000 negatives, 88,000 of which were Pruitt’s and the remainder Shanks’. Some were glass plates, some were highly flammable cellulose nitrate, and some were acetate, their layers expanding and contracting with changes in humidity and temperature, becoming pockmarked, warped and stuck together — a deterioration that could be avoided in a controlled storage setting.

Hudson (center) with his boyhood friends Mark Gooch (left) and Birney Imes (right) in the early stages of working with Pruitt’s collection. Photo courtesy of Berkley Hudson ’03 (PhD)

The Possum Boys, however, didn’t have a controlled setting. They moved the negatives and plates to the town’s Masonic Temple, which David Gooch owned. In 2005, Hurricane Katrina blew out some of the windows.

“We started to realize we couldn’t manage all of this,” Hudson said. “These images had stories we’d never heard about our town, and they needed to be saved. So that was our goal, to save them, research them, exhibit them and publish them. It just took us longer than we expected.”

In 1997, Hudson wrote a story for The California Sunday Magazine about storytelling in America. It caught the eye of Lloyd Cotsen, a multimillionaire philanthropist and former head of the Neutrogena Corp. He hired Hudson and Burch to travel around the country interviewing storytellers about their processes. Cotsen was among those who encouraged Hudson to come to Carolina in 1999 to work on a doctorate in mass communication, with a certificate in folklore. Hudson was drawn to what he said were “the amazing” faculty and students at UNC, as well as the resources at the libraries at the University and Duke that would connect with his interest in folklore, visual studies, the American South and storytelling. “I became like a free-range chicken in the fields of knowledge of UNC,” he said.

The daily life of a community

In 2003, Hudson, having written his dissertation about the Pruitt collection, was about to earn his doctorate when he met with his mentor, William Ferris, associate director of the Center for the Study of the American South and former chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities; Joe Hewitt ’60 (’66 MSLS), associate provost for university libraries; and UNC professor emeritus of history Joel Williamson, who had been the senior associate director of the Center for the Study of the American South. They spent the next two and a half years negotiating a sale of the photographs to UNC.

Stephen Fletcher, a photographic archivist at Wilson Library, traveled to Mississippi to evaluate the collection. The Possum Boys, knowing the photos would be protected at Wilson and digitally scanned to be shared with the public, sold the collection at a discount after appraisers from one of the nation’s foremost art appraisal firms, Penelope Dixon & Associates, concluded that the research potential for the archive was immense.

Once the sale was completed, Fletcher returned to Columbus, bought a shop vac and sucked up years of dust, bugs and paper fibers from envelopes that held the negatives. He grouped the images loosely by date, created a color-coded map indicating in which decade each was taken, then boxed up everything to ship back to Carolina.

The Southern Historical Collection was founded more than 90 years ago by historian J.G. Hamilton, who specialized in the reconstruction era. “He was basically an apologist for the Ku Klux Klan during Reconstruction,” said Biff Hollingsworth ’08 (MSLS), collecting and public programming archivist at Wilson Library.

Hollingsworth said Hamilton wanted to collect the papers of the white aristocracy of the South. The collection has evolved and now attempts to document the people who were excluded in historical narratives. The Pruitt-Shanks collection helps fill some of those gaps.

North Carolina Collection photo archivist Stephen Fletcher cleans Pruitt’s materials in Mississippi, fall 2005. Photo courtesy of Berkley Hudson ’03 (PhD)

“The significance of the collection is the vast inclusive nature of photographs in a single community where you have Black, white, men and women of all ages captured in daily life,” Ferris said. “Photography is a deep look at our history as a family, as a community, as a nation, and these photographs allow us to pull back the veil and see what life was like in a single community.”

Hudson continues to uncover the stories behind the images. In the early 2000s, he set up in Columbus’ library and advertised that he was in town to hear stories. Social worker Jessie Koonce, a Black woman, told him about the humiliation of using a side entrance into the theater and having to cross the street to the bus station if she needed to use the bathroom, he wrote in Possum Town. Librarian Chebie Gaines Bateman described a visit by Tennessee Williams, who grew up in Columbus.

Hudson, intent on identifying the people in the photographs and perhaps figuring out what they were doing, has analyzed the notch system on the edges of Pruitt’s acrylic film negatives to determine when the photos were made. He’s zoomed in on license plates in the photos, and calendars hanging on walls. He’s combed through ancestry databases, hoping to find the stories behind the photos and perhaps the truth about his town.

“Some of these stories would never come to light, but they have,” Duke University professor Rankin said, “first, because the picture exists, then because the image reverberated to Berkley Hudson and then because Berkley’s obsession kept the project going. Add his ability to write and the gumshoe research that he’s done as a journalist — that’s what archival images can do. They’re sort of in stasis, and then all of a sudden, they start moving.”

Now, in the book and the exhibition, the images are being shown worldwide.

“Regardless of your political beliefs, religious beliefs, background, or economic status,” Hudson said in February at the exhibition’s opening in Columbus, “I think you can discover things by looking at these pictures slowly, by asking who’s included and why, who’s excluded and why, what’s pictured, what’s been left out. That can lead us to a common ground of understanding our past, our present and our futures.”

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.