Head for the Stars

You’ve probably seen the stellar images from the James Webb Space Telescope. It was named for a Carolina alumnus who helped set America on a course to become the world’s technological and economic leader.

by Michael Hobbs ’15

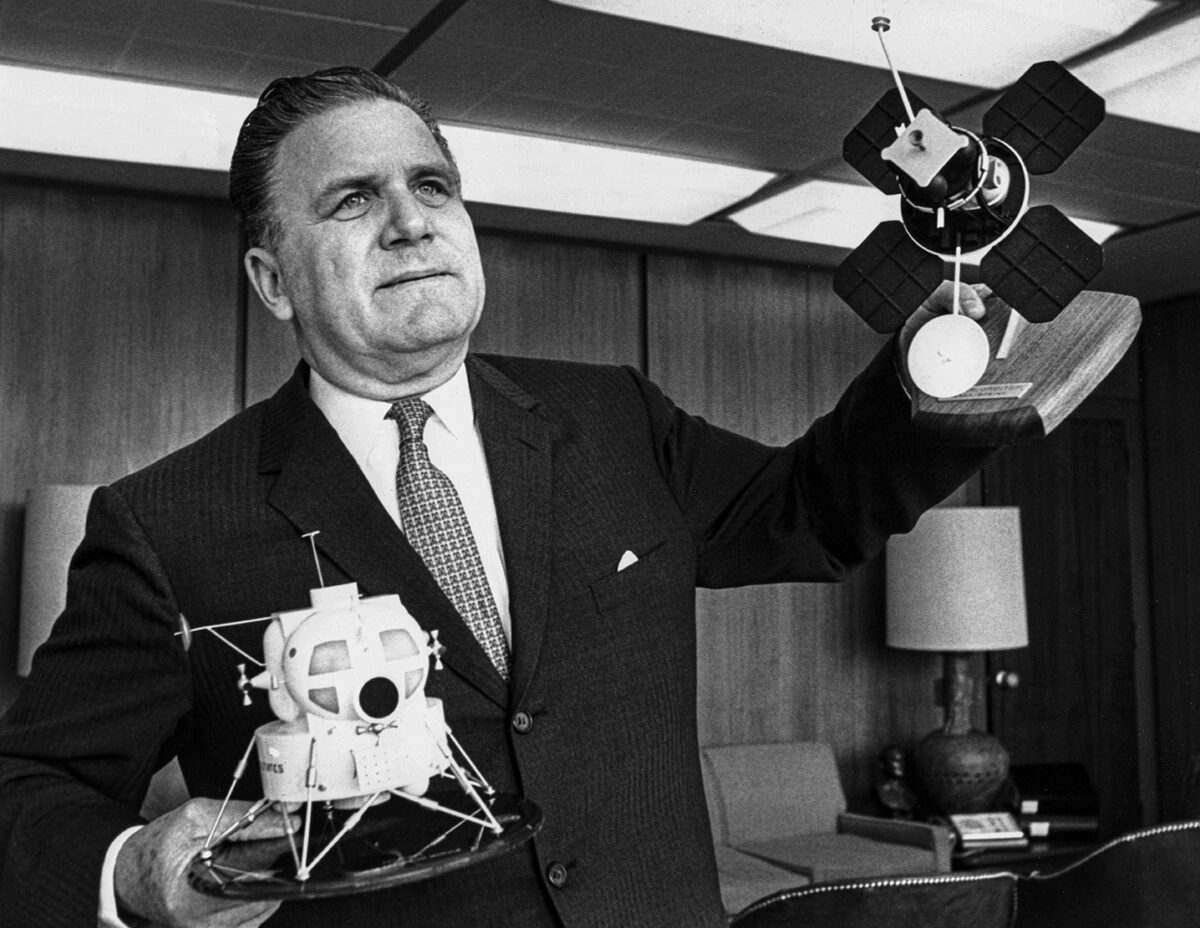

Webb holds models of the Lunar Excursion Module and the Lunar Orbiter in 1963. He led what became the largest engineering project in history — 10 times larger than the Manhattan Project and with personnel numbers rivaling America’s involvement in the Vietnam War. Photo: NASA

Now we can see almost to the beginning.

With its astounding far-reaching images of the universe, the James Webb Space Telescope is heralding a generation of discovery that promises to answer, and ask, questions about our place in the universe.

The telescope is named after James E. Webb ’28, who came out of rural North Carolina to play an outsized role dragging, and sometimes shoving, America into its place as a political, technological and economic leader in the world we know today.

Webb is most widely known as the head of NASA during the Apollo program, which put American astronauts on the moon in 1969.

“James Webb was the guy who gave us the wherewithal and the courage to actually explore beyond this rock,” said Sean O’Keefe, who in 2002 as NASA’s highest-ranking official chose to name the telescope after Webb.

But Webb’s impact wasn’t limited to space. In a succession of government posts, this man from Granville County helped lay foundations of a modern America and to address its social issues. While leading NASA, he saw getting to the moon ahead of the Soviet Union as just one part of his ambitions for the space agency and for the United States.

“As astronauts walked the moon, Webb proclaimed to all who would listen that Apollo’s real achievement lay in demonstrating that a democratic nation could out manage an authoritarian state,” wrote historian Henry Lambright in his biography of Webb, Powering Apollo: James E. Webb of NASA. “He said that if the United States could go to the moon, it could solve its other public problems.”

Politics, business, public service

Webb in the Gemini trainer, June 1965. Photo: NASA

Webb was born at the dawn of human flight, in 1906, four months after the Wright brothers secured their patent for the world’s first powered airplane. On his way to managing America’s leap into space, Webb lived a life a little like Forrest Gump’s: He showed up and played key roles in a parade of seminal moments as the United States asserted its leadership in the late 20th-century world.

In his first job in Washington, D.C., Webb worked as an aide to U.S. Rep. Edward Pou (class of 1885) of North Carolina, who, as chair of the House Rules Committee, served as a traffic cop clearing the way for Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal legislation. Webb sat in on key meetings — and stood by during Pou’s daily afternoon poker games where political deals were often hammered out — helping the congressman move legislation, all the while learning the ways of Capitol Hill.

As the nation prepared for and fought World War II, Webb was hired as personnel director at Sperry Gyroscope Co. — which produced gyroscopes, navigational equipment, bomb sights, machine-gun turrets and other fighting gear — and rose to vice president within seven years, overseeing the company’s growth from 800 employees to more than 33,000.

Late in the war, Webb went from serving in the Marine Corps Reserve to active duty, commanding a unit at Cherry Point that produced portable radar equipment bound for use in the island-hopping warfare of the Pacific theater.

After the war, Webb served in the White House as budget director for President Harry Truman, working as White House liaison to the Hoover Commission, which studied executive branch roles and structures needed in a postwar world. Webb stacked the commission’s staff with personnel who supported the administration’s view that the U.S. needed a strong presidency.

As budget director, he helped build the Marshall Plan for postwar recovery in Europe. He created the government’s Economic Indicators measures, a set of charts updated monthly to gauge economic activity. He also instructed all government agencies to submit to him the amounts they were spending on research and development work. It was the first time the data had been collected in one report, and it helped make the case for creating the National Science Foundation.

Truman promoted Webb to the No. 2 position at the State Department, where he served during the outbreak of the Korean War and as the U.S. government organized for the emerging Cold War with the Soviet Union. Webb had a hand in negotiating and drafting the executive orders and legislation that established the American national security infrastructure we know today — a reorganized State Department, a new Department of Defense, intelligence agencies and the laws that govern them.

Bruised but deeply experienced after six years of bureaucratic battles, including losing influence with Secretary of State Dean Acheson, Webb left government in 1953. He considered a job in North Carolina. “I had hoped to come to Chapel Hill as the Dean of the School of Commerce and participate over the next 25 years or so in the development of that region served by the University,” Webb wrote to a friend.

Instead, he accepted an offer to go to Oklahoma to run a subsidiary of Kerr-McGee Oil Industries Inc., work that strengthened his corporate and political connections. At the company, Webb helped establish the Frontiers of Science Foundation of Oklahoma, which reflected his interest in promoting science education and the development of scientific research in the private sector and at universities.

Webb used his position at NASA — and the agency’s multibillion-dollar budget — to push for reforms he believed were needed for America to secure a leadership role in a technocratic age.

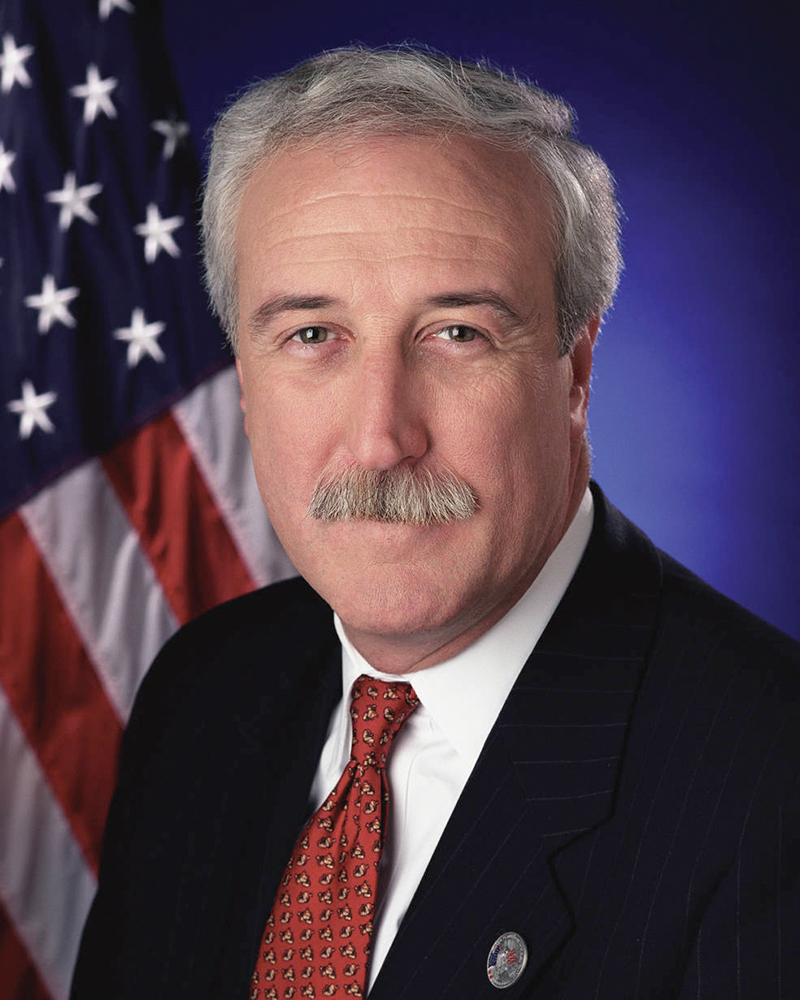

“James Webb was the guy who gave us the wherewithal and the courage to actually explore beyond this rock. … But for James Webb there would be no NASA.” — Sean O’Keefe, former Administrator of NASA. Photo: NASA

A moonshot

In 1961, President John Kennedy recruited Webb to lead NASA. Webb had not sought the job, arguing that he didn’t have a scientific background. But Kennedy told Webb he didn’t want a scientist. He needed someone who knew how to get things done in Washington. Webb took the job.

Fourteen weeks later, in a televised midday speech to Congress, Kennedy called for landing men on the moon by the end of the decade. It was audacious. A Gallup poll shortly before the speech found nearly 60 percent of respondents opposed spending billions of dollars to go to the moon. But Kennedy framed the task as one to demonstrate to the world that the U.S. could surpass the Soviet Union’s leadership in space flight.

Webb got it done. He led what would become the largest engineering project in history, 10 times larger than the Manhattan Project, which built the first atomic bomb. From 1960 through the end of the Apollo program in 1973, NASA spent $49.4 billion — in 2020 inflation-adjusted dollars, $482 billion, according to an analysis conducted by the Planetary Society, a nonprofit advocacy group. In personnel numbers the Apollo program rivaled American involvement in the Vietnam War.

“No one has ever adequately pointed out that, under Jim Webb, NASA was a magnificently managed program,” said business management scholar Leonard Sayles. “As a society, we went from almost zero knowledge of man in space to a fully operational space program in less than 10 years. I’ve seen a company take that long to build a new plant or get a new process working. Webb achieved an enormous accomplishment in organizational leadership. He contributed more than one can easily say to our national welfare.”

Webb exerted influence beyond the moon mission. He used his position at NASA — and the agency’s multibillion-dollar budget — to push for reforms he believed were needed for America to secure a leadership role in a technocratic age. He frequently advocated for marshaling America’s intellectual, manufacturing and managerial powers to demonstrate to the world that democratic governments can accomplish far-reaching goals.

Webb (far left) and other officials, including Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson and President John F. Kennedy, listen to a briefing on a Saturn I launch in 1962. Webb wasn’t afraid to go toe-to-toe with Kennedy. In a 1962 meeting, the president exhorted Webb to agree that the moon program was NASA’s top priority. Webb refused, saying that doing so would make all of NASA’s other projects targets for budget cuts. Photo: NASA

Webb communicated frequently with senators and congressmen to build support for NASA’s initiatives. In a 1963 letter to Tennessee Sen. Estes Kefauver, chair of the Antitrust and Monopoly Subcommittee, Webb wrote, “As a nation we are in a period of vast and rapid change when we must find better ways to use and guide the giant forces at play to ends that will prevent war and make for a better world. The management systems, the new kinds of relationships we are developing in the government-university-industry field, and the research in methods of organization which we are conducting, have the potential to powerfully reinforce our democratic institutions.”

Public universities were a key to mustering American power to tackle big problems, Webb believed. He used NASA funding to issue grants to public universities to allow them to compete with better-endowed elite schools and to expand scientific and technical education programs. In the mid-1960s, Webb — through NASA’s Sustaining Universities Program — distributed more than $50 million a year in research grants and contracts to state universities, including historically Black colleges. Much of the money was in the form of seed grants intended to allow colleges to expand basic research programs.

Rather than awarding graduate funding directly to students, NASA funded fellowships that enabled colleges and universities to compete in recruitment of top graduate students. By 1970, more than 4,000 doctorates had been earned by SUP-funded students.

Webb also worked to transform the field of public administration into a profession, believing effective management of government programs was necessary to address the nation’s problems. While Webb was largely a self-taught student of management theories, he worked to formalize the study of government management by leading work to establish the National Academy of Public Administration, which works to advance good government practices.

The Lavender Scare

Back to the Beginning

The James Webb Space Telescope, 100 times more powerful than the Hubble Space Telescope, is designed to peer into the vast distances of the universe. A consortium including NASA, the European Space Agency and others launched the Webb Telescope on Christmas Day 2021. Then came what some in the astronomy community called weeks of terror, as the observatory, folded into its rocket casing like a giant origami project, went through an exceedingly complicated unfolding of heat shields and gold-plated mirrors and calibration of its exquisitely intricate instruments. NASA said the launch and deployment had 344 “single points of failure,” any one of which could have turned the telescope into a $10 billion piece of space junk.

Imagine the tension of watching a Carolina basketball team, one point behind with only seconds on the clock, and a Tar Heel at the free throw line — multiplied 344 times.

Because it can detect light from billions of light years away, the telescope also serves as a time machine, seeing back to just after the Big Bang — the beginning of the universe. It will show us stars and galaxies born before Earth was formed.

That most distant light comes from stars and galaxies speeding away from us, so their waves of light are stretched. Think of the way a blaring train horn shifts to a lowering note as it passes, the sound stretching into longer waves as the train moves away. Light from distant stars and galaxies does the same thing, stretching into an invisible-to-our-eyes portion of the electromagnetic spectrum — the infrared.

The Webb telescope, among its other abilities, is designed to see that ancient infrared light.

“We’re going to see the universe in a way that we’ve never looked at it before,” said Susan Thompson Mullally ’01 (MS, ’04 PhD), deputy project scientist for the Webb telescope. “It feels like, ‘Oh, we’ve seen everything out there in the universe.’ But the truth is we’ve had very little coverage.

Susan Mullally ’01 (MS, ’04 PhD), deputy project scientist for the Webb telescope: “We’re going to see the universe in a way that we’ve never looked at it before.” Photo: Susan Mullally ’04 (PhD)

“There was a time in which suddenly stars and galaxies started to form,” Mullally said. “Hopefully, Webb will be able to observe those very stars and galaxies, right at the very birth of the universe.”

The telescope also will be used to study exoplanets, planets that orbit stars of solar systems other than our own. Both Mullally and Provost Chris Clemens, the Jaroslav Folda Distinguished Professor of physics and astronomy who was Mullally’s doctoral adviser when she was at Carolina, plan to study exoplanets using data from the Webb telescope.

When a distant planet passes in front of its star, spectrometers aboard the telescope will examine the light passing through that planet’s atmosphere, giving us data that describe the gasses there.

“Will they be like the planets we have in our solar system, or will they be completely different?” Clemens said. “And if they are different, what will they be? It’s like Darwin going to the Galapagos and seeing animals from a different setting. … Are we typical? Will our planets be like those planets? Or will we find whole new classes of planets with different atmospheres?”

Mullally, who grew up with a mathematician mother and a chemist father who both stoked her interest in math and science, including once having her skip school to watch a solar eclipse, said she finds moments to ponder what it all means.

“I feel incredibly lucky that I get to work in an area where I even get to think about the awe factor,” she said. “The truth is, day to day, the work is very similar to a lot of other people’s work. You’re on Zoom meetings, and you’re talking and you’re trying to negotiate what’s the best thing to do.

“But at the end of the day, you get to think about how big this universe is that we live in and how much left there is to explore. It’s just delightful to see something new and to then explain it to other people.”

— Michael Hobbs ’15

While Webb looked to the future, he operated in the troubled present of his times. In 1948, biologist Alfred Kinsey, who established the Kinsey Institute at Indiana University, published the groundbreaking Sexual Behavior in the Human Male. Among its findings, Kinsey’s survey found 37 percent of men reported at least one homosexual experience in their lifetimes, with 10 percent reporting they were “more or less exclusively homosexual.”

The report, rather than assuaging American anxieties over homosexuality, inflamed them. It fueled a government persecution campaign — later dubbed “the Lavender Scare” — in which some government departments, stoked by Sen. Joe McCarthy and others in Congress, sought to identify and force out gays and lesbians from government.

“For most of the twentieth century, the most terrible secret one could possibly possess — more terrible, even at the height of the Cold War, than being a Communist — was being gay,” wrote James Kirchick in his book Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington.

The Lavender Scare reached into the State Department and NASA while Webb worked at the agencies. A group of astronomers last year called for NASA to rename the Webb Telescope, arguing Webb either was involved in the purges or should have known enough to stop them. A NASA investigation concluded there was not enough evidence of Webb’s direct involvement to justify renaming the telescope.

Historian David Johnson, author of the book The Lavender Scare, told the journal Nature that it appears Webb’s involvement was an attempt to limit, not inflame, the hysteria being stirred up by congressmen. “I don’t see him as having any type of leadership role in the Lavender Scare,” Johnson told the journal.

Brian Odom, NASA’s acting chief historian, has continued to investigate the documentation of Webb’s work in government, seeking to ascertain whether Webb took a leading role in the purges. He said he could not release findings yet. “It’s a critical issue,” Odom said. “If NASA is going to be committed to diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility, then this is the type of thing we have to know so that we can talk about it.”

Webb also found himself at the center of the Civil Rights movement. He and his team at NASA engaged, with mixed success, to support it. Webb, in his role as NASA administrator and as a member of President Lyndon Johnson’s Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity, personally lobbied on Capitol Hill for passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Webb also enforced Kennedy and Johnson executive orders requiring government contractors to hire Black employees. In one instance widely followed at the time, Webb hinted at the possibility of moving NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center out of Huntsville, Alabama, if segregationist Gov. George Wallace and other officials made life difficult for employees.

The New York Times, in an Oct. 24, 1964, story headlined “NASA May Leave Its Alabama Base,” reported Webb had given a talk the day before to businessmen in Montgomery, saying the agency might move operations out of the state unless race policies were changed.

“The announcement by James E. Webb, NASA administrator, was interpreted by his close associates as a direct slap at Gov. George Wallace of Alabama and the racial policies of his state,” the Times reported.

While the Black community in Huntsville led the campaign to break down racial segregation, NASA played a supporting role, said Odom, co-editor of NASA and the Long Civil Rights Movement. “They identified very quickly that poor race relations in Alabama were going to negatively impact their ability to recruit and retain Black engineers, or anyone, to move there,” he said.

Afraid of losing the economic might of NASA’s operations, civic leaders in Huntsville worked to ease tensions. Huntsville became the first city in Alabama to integrate its schools.

A science infrastructure

O’Keefe, who was NASA administrator when the deep-space telescope was being developed, said he chose to name the observatory after Webb because of Webb’s advocacy for NASA’s science missions. O’Keefe said Webb’s work to sustain support for the missions — in addition to manned space flights — made NASA the preeminent science organization we know today.

“But for James Webb there would be no NASA,” O’Keefe said. “There would be no focus on this broader set of objectives.”

Webb’s fight for NASA’s science included going toe-to-toe with President Kennedy. In a 1962 White House meeting, which was recorded on Kennedy’s secret taping system, the president exhorted Webb, several times, to agree with him that the moon program was NASA’s top priority. Each time Webb refused, saying that doing so would make all of NASA’s other projects targets for budget cuts, according to the recordings.

Kennedy, referring to the moonshot effort, asked Webb: “Do you think this program is the top-priority program of the agency?”

Webb: “No, sir, I do not. I think it is one of the top-priority programs, but I think it’s very important to recognize here” that argued missions aimed at scientific discovery were important for motivating researchers.

“Now … all through our universities, some of the brilliant [and] able scientists are recognizing this and beginning to get into this area, and you are generating here on a national basis an intellectual effort of the highest order of magnitude that I’ve seen develop in this country in the years I’ve been fooling around with national policy,” Webb told Kennedy.

Ten months later, in another White House meeting to discuss budget pressures, Kennedy pressed Webb again, questioning the value of the space program.

Webb said NASA science was important “in understanding the forces of nature and applying them right here on Earth and using them for national power. You’ve got to have, sometime, a proof of the theory of how the universe was formed and how it applies back on the scientific concepts.”

Webb told Kennedy the scientific community would appreciate his leadership and that young people especially were excited by the prospect of space discoveries.

“The high school seniors and the college freshmen are 100 percent for man looking at three times what he’s never looked at before,” Webb said. “He’s looking at the material of the Earth, the characteristics of gravity and magnetism, and he’s looked at life on Earth. And he understands the universe just looking at those three things.”

He added: “And if we find some life out beyond Earth, these are going to be finite things in terms of the development of the human intellect.”

Odom called Webb’s defense of NASA’s basic science programs “critical” to establishing NASA as a premiere engine of scientific discovery.

If going to the moon was NASA’s primary concern, everything else would have become peripheral, Odom said. “But what Webb is able to do is he thinks broader. What he understood was that this agency can’t just be about putting a human being on the moon.”

‘Public Servant’

Throughout the intense media focus on NASA and the Apollo program, Webb worked to stay out of the limelight, preferring that astronauts and others receive public attention and adulation. During the race to the moon, Webb never appeared on the cover of a newsmagazine.

As Lyndon Johnson’s presidency was ending, Webb resigned from NASA a month before the 1968 elections to allow the next president to appoint his own administrator. When Neil Armstrong stepped onto the moon just nine months later in July 1969, Webb was at home, watching on TV.

Webb stayed engaged in work to promote science education, including service on the board of regents of the Smithsonian Institution where he helped establish the National Air and Space Museum.

Webb died in 1992 at the age of 85. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery on a hillside of gravestones of American potentates.

His epitaph simply reads: “Public Servant.”

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.