Hot Spotlight, Cool Prosecutor

Posted on May 7, 2021

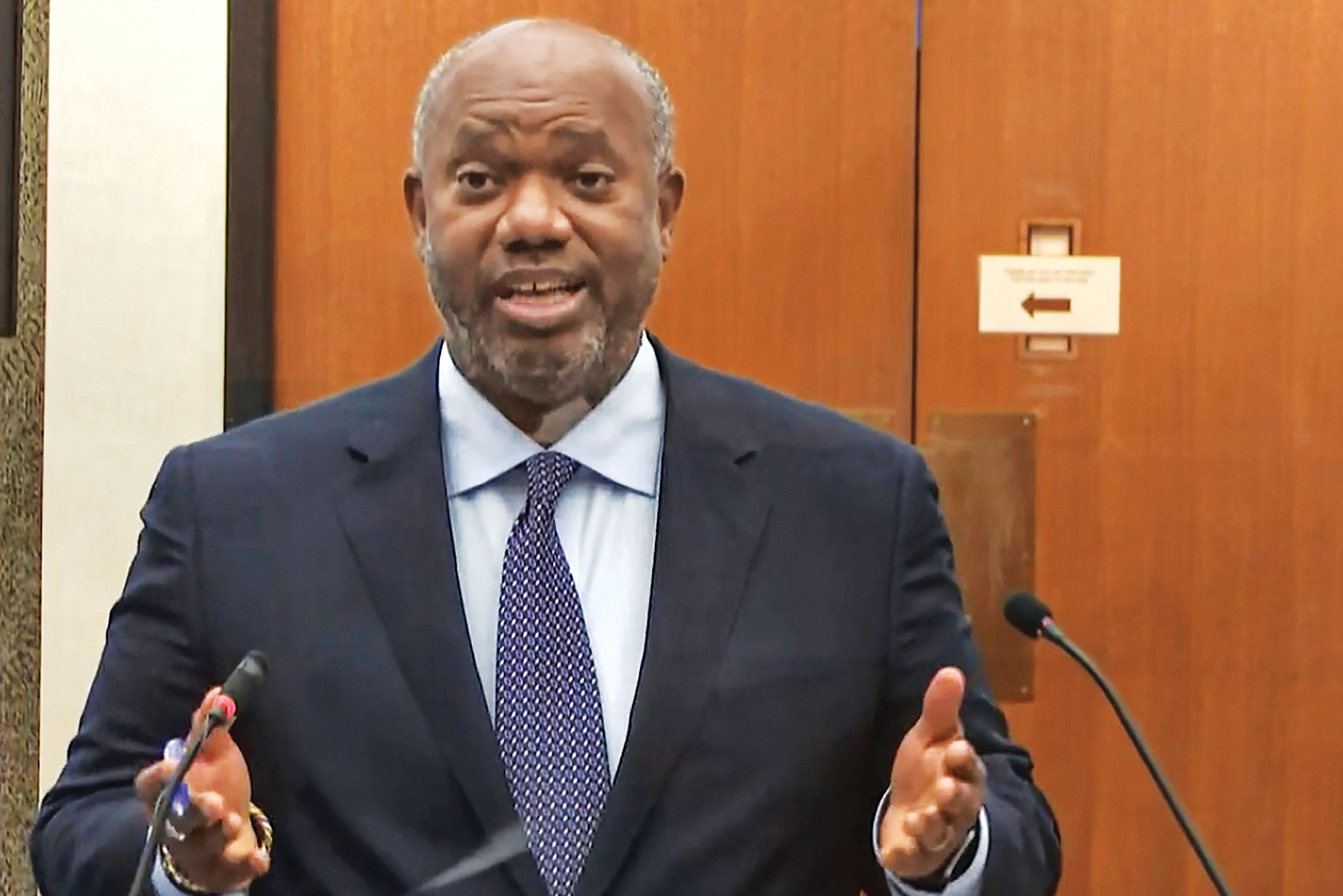

Jerry Blackwell ’84 doesn’t practice criminal law. He heads a firm that defends Fortune 500 companies in high-stakes, complex civil litigation. (Court TV via AP, Pool)

As the eyes of the nation watched, Jerry Blackwell ’84 (’87 JD) took center stage as special prosecutor in a Minneapolis courtroom in late March and did what a good lawyer does best: He told jurors a story.

Speaking softly, with the hint of a Southern accent, Blackwell recounted events of the day last summer when George Floyd died. He described how former police officer Derek Chauvin kneeled on Floyd’s neck for 9 minutes and 29 seconds, how Floyd cried out 27 times that he couldn’t breathe and how bystanders felt powerless to intervene.

“He put his knees upon his neck and his back, grinding and crushing him, until the very breath — no, ladies and gentlemen — until the very life was squeezed out of him,” Blackwell said, arguing that Chauvin was guilty of murder.

Dressed in a crisp white shirt and gray suit, Blackwell spoke for nearly 50 minutes, his voice even, his manner calm, explaining complicated medical terms in ways jurors could understand, all the while seeking to foster trust and credibility with them during his opening statement.

“Who is Jerry Blackwell?” one newspaper headline blared afterward. Other media followed with the same question.

Blackwell is not a prosecutor. He doesn’t practice criminal law. He heads a corporate law firm in Minneapolis, defending Fortune 500 companies in high-stakes, complex civil litigation. His clients have included 3M, General Mills and Walmart. He also represented the late singer-songwriter Prince, a Minneapolis native, as “trusted adviser and counsel … in all his personal and professional matters.”

But those who know Blackwell professionally and personally say they were not surprised that Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison turned to him for help in one of the nation’s most anticipated and emotionally wrenching criminal trials in years — ending with the rare conviction of a police officer for murder.

“Jerry is a titan in our legal community,” said Uzodima “Frank” Aba-Onu, president of the Minnesota Association of Black Lawyers. “He knows how to bring out the best in people. He’s a good soul.”

Those who know Jerry Blackwell ’84 (’87 JD) professionally and personally say they were not surprised that Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison turned to him for help with the trial of former police officer Derek Chauvin.

A native of Kannapolis, Blackwell was the first of the six children in his family to attend college, according to the Minneapolis Star Tribune. He credits his mother for his decision to go to law school, telling the newspaper in 2012: “[When I was] in the second grade, she saw that I liked reading and said, ‘You should be a lawyer.’ Right there, at 8 years old, I wanted to be a lawyer to make my mother proud.”

Bryan Beatty ’87 (JD) said he recognized Blackwell’s “legal brilliance” when they were law school classmates. “He stood out as someone with exceptional intellect,” said Beatty, former director of North Carolina’s State Bureau of Investigation and former secretary of Crime Control and Public Safety. “He was also very personal and humble, which I continue to find to be a rather rare combination of characteristics — to have that kind of brilliance but also be humble.”

After graduating from law school, Blackwell left North Carolina for Minnesota to work at Robins, Kaplan, Miller & Ciresi because he read in The New York Times that the firm was representing the government of India in the Bhopal gas explosion — one of the world’s worst industrial disasters ever. Blackwell was interested in international litigation and product liability, and he was eager to be part of such a big case.

He became a partner at the firm at 31. He co-founded his current firm, Blackwell Burke P.A., in 2006 and has successfully defended corporations in lawsuits filed by people claiming they were injured by exposure to asbestos, benzene and other chemicals.

In his 34 years in Minneapolis, Blackwell has worked to diversify the membership of the bar and the state judiciary. He co-founded the Minnesota Association of Black Lawyers in 1995 and has served as a mentor to younger lawyers. Last year, while Minnesota prepared to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the lynchings of three Black men accused of raping a white woman in 1920, Blackwell won the first posthumous pardon in state history — for a fourth Black man, Max Mason, who avoided the lynchings but was wrongly convicted of rape.

During the pardon hearing, Blackwell compared Mason to George Floyd and “tens of thousands of other people of color” who are viewed through a stereotypical and racist lens — “that they are other, that they are dangerous, that they should be imprisoned, restrained, subjugated, overly policed, unduly stopped, searched, harassed, disregarded or worse, as we have all recently seen on live television.”

Ellison, the attorney general, was one of three members of the pardon board. A month after the hearing, he asked Blackwell to help prosecute Chauvin. Blackwell volunteered without pay.

“He’s very well-prepared professionally to do this,” said Raleigh attorney Jon Williams ’85 (’90 JD), who got to know Blackwell when they were undergraduates at Carolina. Williams said Blackwell was his resident adviser in Avery — “very steady, very studious” — and Blackwell recruited him to join the Chi Psi fraternity.

“In dealing with product liability cases, attorneys are often dealing with issues of death and disfigurement and with medical evidence,” Williams said. “He really has an outstanding professional background to deal with that kind of evidence and the emotions in the courtroom.”

The two lawyers got together for dinner when Williams was in Minneapolis for a conference a couple of years ago. Williams remembers Blackwell talking then about the challenges of managing a large corporate law firm. “He had had a lot of stress in his life, which was causing some health issues,” Williams said. “He made a very radical and intentional effort to figure out new ways to deal with the stress.”

One way was through meditation. Blackwell is now a proponent of the technique; in 2019, he gave a talk in Asheville at the annual meeting of the International Association of Defense Counsel titled “Meditation: Learn the Techniques That Can Transform Your Life.” Blackwell also took up gardening and raising honeybees.

When asked by a reporter once where he goes to get away from work, Blackwell mentioned meditation but also said, “My wife is a great oasis!” He courted Tiffany Wilson Blackwell by anonymously sending red tulips and purple irises to the beauty salon she owns, according to the Star Tribune. They married in 2011.

The couple care deeply about their community, said Sarah Carthen Watson, legal director of the Louisiana Fair Housing Action Center. Carthen Watson thinks of Blackwell as “Uncle Jerry” although they have no blood relation. Her mother is part of a tight-knit community of Black lawyers in Minneapolis — a coterie of “aunts” and “uncles” that Carthen Watson said helped raise her and other “cousins.”

“Uncle Jerry is always looking out for us,” Carthen Watson said — and, she added, looking out for Minnesota’s Black community at large. She wasn’t surprised he volunteered to help prosecute Chauvin, who was convicted on all counts.

“He sees not only what this case has meant to the community but also what the outcome of it can mean,” she said. “He’s one of those people who’s called to serve.”

— Elizabeth Leland ’76

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.