Long List of Demands Dominates Meeting on Race

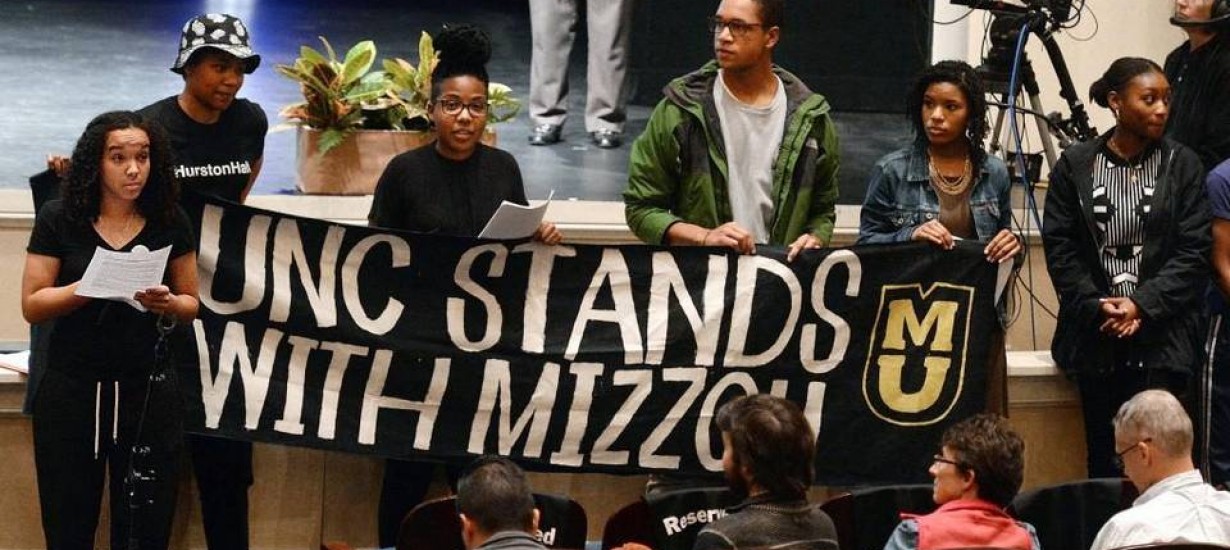

Clarence Page, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who was called in to moderate a town hall meeting on race and inclusion on the campus on Thursday, had barely begun to speak when a group of students took control of the event and recited a long list of demands to a nearly full Memorial Hall.

Calling themselves “a collective of students who are combating anti-blackness on this campus,” the group called for mandatory education on racial sensitivity for everyone who works, teaches or studies on the campus; a voice for students of color in the hiring of top-tier administrators; more aggressive hiring of faculty of color; the hiring of more mental health professionals at UNC with experience specific to the needs of minorities; and disarming and training of campus police in de-escalation techniques.

The complete list of demands was quite a bit more ambitious: “the elimination of tuition and fees” — more specifically a moratorium on tuition increases until all students are graduating debt-free; the firing of the recently hired new president of the UNC System, Margaret Spellings; an end to the use of the SAT, ACT and other standardized tests in admissions; free parking and free child care for all who work on the campus; and the right of all University employees to unionize.

The group reiterated that UNC must take down the Silent Sam Civil War monument and any other campus monuments to the Confederacy and rename the former Saunders Hall for the author and activist Zora Neale Hurston. It also called for gender nonspecific housing and bathrooms on the campus.

Demands were anticipated in the town hall, called last week by Chancellor Carol L. Folt in response to escalating racial protests at other universities across the country, after some 300 people gathered at a rally on Nov. 13 to hear the students’ grievances over what they called the hostile racial environment on the campus.

Twenty-five minutes passed before Page, many of whose awkward remarks between speakers were met with silence and quizzical stares, spoke again. Most of the some 25 people who stood during the reading of the demands then walked out after announcing a news conference outside the hall.

For two and a half hours, the audience heard many of the same people who spoke at the Nov. 13 rally. Their message is that Carolina often is not a welcoming or even safe place for people of color and that the largely white faculty, student body and administration have not made sufficient effort to understand the experiences of African-Americans and other minorities.

“Being black at Carolina is constantly waking up, thinking, ‘Am I good enough to be here?’ ” a freshman biology and political science major said. “Being black here is very, very difficult.”

The word microaggression — a buzzword for perceived individual, everyday (and even unintentional) racial slights — was repeated throughout the evening. One black student, sophomore Ashley Sapp, shared an example: She said two white people talking while sitting behind her made it difficult for her to hear the speakers, and when she politely asked them to be quiet, she was told that they were just expressing themselves and that if she didn’t like it she could move.

One of the more common demands among the speakers was that UNC establish programs to educate all on the campus to take coursework on the University’s history, specific to its building and maintenance by slaves in the 18th and 19th centuries, its honors for people who advocated and practiced white supremacy, and its refusal to employ black faculty or admit black students until the mid-20th century.

The group that formally presented demands, which represented the Real Silent Sam Coalition and other organizations, called for mandatory teaching of “the ways in which racial capitalism, settler colonialism and patriarchy structure our world.”

Page repeatedly discouraged speakers who asked to hear from faculty and administrators in the audience about what they proposed to do about the racial climate, saying the intent of the meeting was to listen. But several speakers called on faculty to become engaged on the issue and on students to do a better job of making their frustrations understood.

“They can’t help us if they don’t know the experiences we have had,” a freshman named Donna said. “Explain our experiences — we can’t just make demands if they don’t know where we are coming from.”

The speakers, some of whom were prepared and some who were moved by others’ comments to go to the microphone, ran the gamut. Some were African-American; some were not.

A member of the Lumbee tribe said she was put off by a “minority move-in day” event that she said felt exclusionary. Freshman Kennedy Locklear, also of the Lumbee tribe, said the Oct. 12 University Day commemoration should be indigenous people’s day, “because a day that currently recognizes a man that is responsible for the mass murder of my native people is completely unacceptable.” University Day honors the laying of the Old East cornerstone by William Davie, who introduced a bill in the N.C. General Assembly in 1789 that chartered the University and is considered the University’s founder.

Jennifer Ho, an associate professor in the English and comparative literature department, said that “amazing classes” are now offered on race and intersectionality. Ho said students in her class on mixed-race America “don’t always agree, and they have vastly different opinions, but they listen to each other and they understand that institutionalized racism and white supremacy are very real and very tied to the history of UNC-Chapel Hill.”

A student who said she is an undocumented immigrant decried the requirement that North Carolinians of her status must pay out-of-state tuition.

Senior Ajene Robinson-Burris said students must learn to work within the existing system. To administrators, she said, “I know some of this might come off as a little defensive, but try not to grow feelings of spite against students for showing their emotion, because this is a very emotional issue.” To students: “We all need to educate ourselves more on how to be active and how to be those activist students we’re trying to express ourselves to be.”

Folt took the stage briefly at the end of the meeting and said: “You can’t have been listening to this without feeling the frustration. I hear it loud and clear that people want action. But I also heard a lot of action that people suggested — many of them I might not have heard before.

“We couldn’t have heard more strongly that people want us to take a leadership role in training; we couldn’t have heard more strongly that people want better spaces and more spaces in which to find a place to be together. I don’t think the faculty could have heard more strongly the respect that the students have for them. We need to be better about explaining what actions we are taking.”

Last week, Folt announced that she had appointed G. Rumay Alexander as a special assistant. A Carolina faculty member since 2003 and an award-winning national leader in diversity and other workplace issues, Alexander is expected to “more closely integrate new and related initiatives that are arising across campus to accelerate diversity, inclusion, and family and work-life balance,” a statement said.