Office of Civil Rights Cites UNC Failures in Handling Sexual Assault

Posted on June 27, 2018

Andrea Pino’s blue toenails in 2013 alluded to her dream school. The “IX” tattoo on her ankle declared her commitment to seeing colleges improve how they respond to sexual assaults. Pino, who graduated in 2017, and Annie Clark ’11, have been outspoken advocates of change as the Office of Civil Rights investigated more than 200 schools, including UNC. (File photo)

The U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights has found that the University failed to respond promptly to some sexual assault and sexual harassment complaints because staff were not adequately trained to do so and that UNC failed to adopt and publish grievance procedures for the prompt and equitable resolution of student, employee and third-party complaints alleging discrimination on the basis of sex.

A letter from the Office of Civil Rights said that the OCR “has concerns regarding whether the University provided prompt and equitable responses to complaints of sexual harassment and sexual violence, of which it had notice; and, if not, whether such failure allowed individuals to continue to be subjected to a sexually hostile environment that denied or limited their ability to participate in or benefit from the University’s program.”

The letter was sent to the University and to four former students and a former administrator who had filed complaints. It comes five years after the OCR placed UNC under investigation as a result of the complaints.

The University, without admitting to any violation of law, agreed to review and, if necessary, revise its grievance procedures and report to OCR by November. It agreed to augment training programs for staff who are responsible for receiving complaints and reports of sexual violence and other forms of sex discrimination.

The OCR based its decision largely on information provided by the University and the complainants in 2011 and 2012. It acknowledged that changes put in place after that time had improved UNC’s handing of sexual harassment cases. The OCR said that it “reviewed 285 complaints under the current policy from 2014 to 2016, and found that UNC generally conducted adequate, reliable and impartial investigations of the complaints” but that investigators still “had concerns about whether the university provided timely resolution of the complaints.”

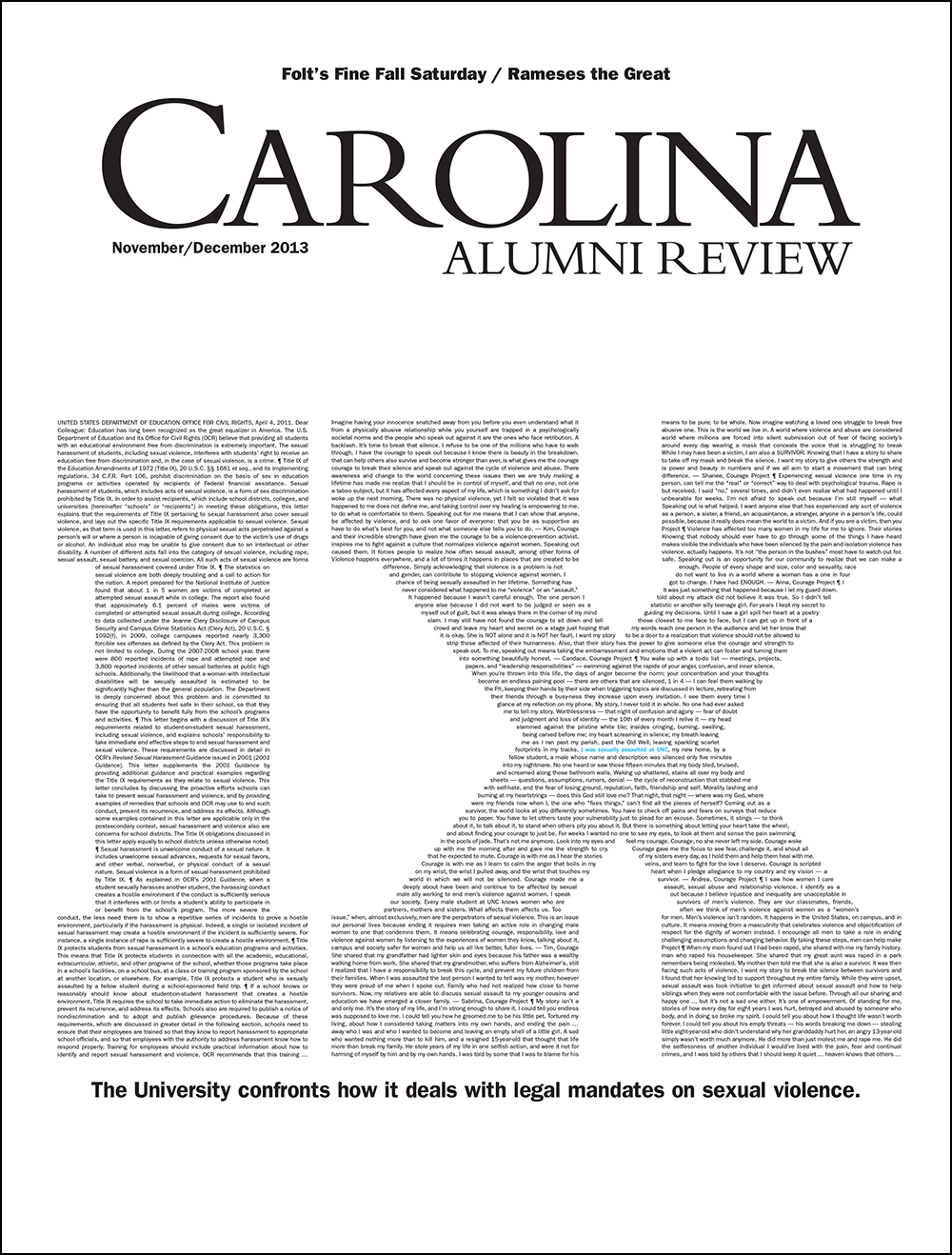

Title IX was enacted in 1972 to prohibit gender discrimination in education programs that interrupt a student’s ability to fully participate in her or his education. (Cover design by Jason Smith ’94)

The OCR acknowledged improvement in Chapel Hill: “During the course of its investigation, OCR recognizes that the University has been proactive regarding its efforts to maintain a campus environment free from discrimination, harassment, and related misconduct, including sexual violence and sexual assault, including through strengthening its Title IX response policies, procedures, resources, and outreach.”

The OCR did not specifically address any of the complainants’ individual claims.

UNC was one of the starting points of what became a network of assault victims across the country who called out their schools on what they saw as often poorly focused, overworked and poorly trained counselors, investigators, health care providers, police and adjudicators in uncoordinated patchworks of offices and agencies.

Outside of a college environment, sexual assault is dealt with by law enforcement and the courts — or not at all. But a university is a protectorate, and it has no choice but to be involved, both in finding a path to justice and in supporting victim and perpetrator in a way that satisfies government standards.

Two UNC alumnae who said they were raped while they were students were at the forefront of the movement. Annie Clark ’11 and Andrea Pino ’17 were outspoken advocates of change in a time when the OCR was investigating many schools. In May 2014, UNC was one of an initial 55 institutions being investigated by the OCR for possible violations of federal law over the handling of sexual violence and harassment complaints. Two years later, in May 2016, more than 200 institutions were under investigation.

In a statement to the campus community on Tuesday, Chancellor Carol L. Folt wrote: “The OCR recognized the extensive work that has been done in the more than five years since the complaint was filed when former students highlighted the need for a more accessible Title IX process. We thank our students and countless others across the nation for their advocacy, the 22 members of our sexual assault task force, which was convened in 2013, and others who gave input to our comprehensively revised policy and procedures.

“Nothing is more important to us than creating a culture at Carolina where every member of our campus community feels safe, supported and respected. While this concludes the OCR investigation, it does not conclude our commitment.”

Andrea Pino ’17

Also on Tuesday, The News & Observer published a statement from Pino: “Today the Office for Civil Rights validated our allegations, and we can finally confirm that UNC was indeed in violation of Title IX. Five years later, and at the heels of the #metoo movement and the 46th anniversary of Title IX, I am glad that our complaint pushed campus sexual assault and Title IX to the national agenda, and I hope that Carolina takes this opportunity to recommit to truly making our university a safe and equitable campus for all students.”

Annie Clark ’11

Clark was quoted by The N&O as saying: “UNC is certainly not the only school that has swept sexual violence and harassment under the rug; however, our students have learned from a great place of higher education, and because we have the knowledge, privilege, and power to do so, we have and continue to hold the university that we love accountable. I, like Andrea and so many others, am glad that our complaints have finally been validated publicly, but that is not the case for everyone. We as a society have so much further to go. I want every student to feel safe everywhere, but especially at school — whether that is in kindergarten or college.”

Seven years ago this past spring, in April 2011, the OCR sent to universities receiving federal funding a letter that emphasized that to simply adjudicate assault complaints was not enough: Universities also needed to dedicate sufficient and proper resources to maintain a safe environment and to help those who asked for support, including sufficient training and clear communication to the campus community.

The law behind the letter, known as Title IX, was enacted in 1972 to prohibit gender discrimination in education programs that interrupt a student’s ability to fully participate in her or his education.

Outside of a college environment, sexual assault is dealt with by law enforcement and the courts — or not at all. But a university is a protectorate, and it has no choice but to be involved, both in finding a path to justice and in supporting victim and perpetrator in a way that satisfies government standards.

“I want every student to feel safe everywhere, but especially at school — whether that is in kindergarten or college.”

–Annie Clark ’11

As UNC began reviewing its policies in spring 2012, it became clear that it lacked people with the specialized knowledge and training to meet the government mandate. Speaking of the staff at that time, Winston Crisp ’92 (JD), vice chancellor for student affairs, said: “I don’t believe any of those people was what you’d call a specialist. I think they had a more broad range of training that I’m guessing had to include … sexual assault … my guess is none of them would be what you would call a Title IX specialist.”

Even earlier, administrators in South Building and in student affairs had serious doubts that investigation of sexual assault by the student attorney general and adjudication by the Honor Court made sense, and they relieved the honor system of those duties that spring.

A task force studied the issue for months and created websites designed to make communication about available resources clearer. It mandated better training for students, faculty and staff.

UNC administrators said the letter and other messages from the OCR were their call to action; Pino and Clark, alternatively, leaned toward the view that change had occurred because of actions of people like themselves.

The letter got the University’s attention; the positions of deputy Title IX coordinator and investigator were created before the complaint reached the OCR.

–David E. Brown ’75 is senior associate editor at the Review

More online:

• Student’s Sexual Assault Claim Turns Attention to UNC Policy, September 2016

• University Refines Policies on Sexual Violence, August 2014

• “Sexual Assault and the Law,” cover story, November/December 2013 Carolina Alumni Review

• Task Force to Review How UNC Handles Sexual Assault Complaints, May 2013

• Timeline of Events: An investigation of Handling Sexual Assault Cases, April 2013

• Carolina Creates Full-Time Title IX Post, Names Interim, April 2013

• Feds Will Probe Handling of Sexual Misconduct Case, March 2013

The Review received four CASE District 3 awards related to its November/December 2013 cover story, titled “Sexual Assault and the Law”:

• Grand Award in Graphic Design for the cover, seen at left. (The words inside the “I” of Title IX were from the letter from the U.S. Department of Education warning colleges to improve their prevention of and response to sexual assaults involving students. The words in the “X” were from essays about sexual violence featured in UNC’s The Courage Project.)

• Grand Award in Publications Writing

• Award of Excellence in Best Articles of the Year

• Special Merit Award in Feature Writing