On the Record

Posted on May 31, 2022 This is part of a series on the 100th anniversary of the GAA hiring its first full-time, paid professional staff member for an organization that for 80 years prior had been run by volunteers.

This is part of a series on the 100th anniversary of the GAA hiring its first full-time, paid professional staff member for an organization that for 80 years prior had been run by volunteers.

For a university to be accredited, it has to keep track of its alumni. That’s no small order.

With 350,524 living alumni, a number that increases throughout the year, Carolina’s alumni database requires constant vigilance. Records staff at the GAA, led by Roger Nelsen since 1993, update name changes, addresses, job titles, phone numbers and email addresses, marriages, births and deaths. And that’s only the start.

“The job of alumni records is to make sure information on alumni is as accurate and full and complete as possible,” Nelsen said. The process starts early. “We get information from admissions before students even come to campus.”

Originally, records for alumni were simply cards with the name and address of each alumnus, along with some biographical information, such as date of birth and class year. In 1889, Cornelia Phillips Spencer, who rang the bell to reopen the University in 1875, funded an “alumni catalogue” that listed all 5,866 living and deceased alumni — Carolina’s family bible, The Daily Tar Heel called it. In 1943, Spencer’s son-in-law, James Lee Love (class of 1884), established a fund that would pay for the periodic publication of directories.

In 1922, when Daniel Lindsay Grant (class of 1921) was hired as the GAA’s secretary, the office began using Addressograph stencils to maintain mailing lists to correspond with alumni on such things as ordering football tickets. Grant also published an Alumni History in 1925, a directory of living and deceased alumni, about 15,000 names.

In 1922, when Daniel Lindsay Grant (class of 1921) was hired as the GAA’s secretary, the office began using Addressograph stencils to maintain mailing lists to correspond with alumni on such things as ordering football tickets. Grant also published an Alumni History in 1925, a directory of living and deceased alumni, about 15,000 names.

The GAA also keeps a folder on each alumnus, in which photos, newspaper clippings, alumni survey responses and correspondence are stored. Initially, the files were ordered by the class year the alumnus preferred. If staff didn’t know that class year, good luck finding the folder. (We stopped creating a folder for each alumnus in 1988 and now only open a paper file if we receive a document such as a newspaper article or survey response. Digital documents are stored in a database.)

J. Maryon “Spike” Saunders ’25 (’26 MA) took over as alumni secretary in 1927 and published another directory in 1954. Women known as Morgue Ladies kept the records on colored cards — white for degree holders, blue for those who didn’t graduate, yellow for female students once they married. For every class of graduates, Saunders bought a new file cabinet.

In 1970, Clarence Whitefield ’44 took the helm. The roster of the alumni living and dead had topped 100,000. Directories were published in 1975 and 1984.

In 1973, the University purchased software that computerized alumni records. With the help of Elizabeth Parker, a career administrative secretary at UNC who later received the University’s C. Knox Massey Distinguished Service Award, alumni records began migrating information to a graphical user interface computer system.

Whitefield still saw a place for paper, but the file cabinets had to go. He bought 100,000 manila cardstock jackets. Staff spent a summer sliding the contents of each individual’s file into a labeled jacket and arranged them in alphabetical order on open shelves, like slim volumes in a library.

The manila jackets hold a treasure trove of information found in letters from alumni or newspaper clippings. No item that appeared in a newspaper was too small to put in an alumnus’s folder — a list of pall bearers, out-of-town guests at a wedding, even a notice of a speeding ticket.

In 1982, Doug Dibbert ’70 was hired as secretary and director of alumni affairs, a title that later changed to president. He hired Nelsen in 1993, the year the George Watts Hill Alumni Center opened. When Nelsen took on computer support a year later, he wondered what it would take to computerize all of the information in each alumnus’s folder. At the time, it was too expensive to digitize the entire hard copy file for 1,416 linear feet of folders. So he waited. As technology evolved, the cost of digitization dropped.

Just before the pandemic, Nelsen grabbed a random three-foot-long section of folders and sent them to digitization specialists at Wilson Library. They studied how much material was in the folders, going so far as to count staples and paperclips that would have to be removed before digitization, Nelsen said.

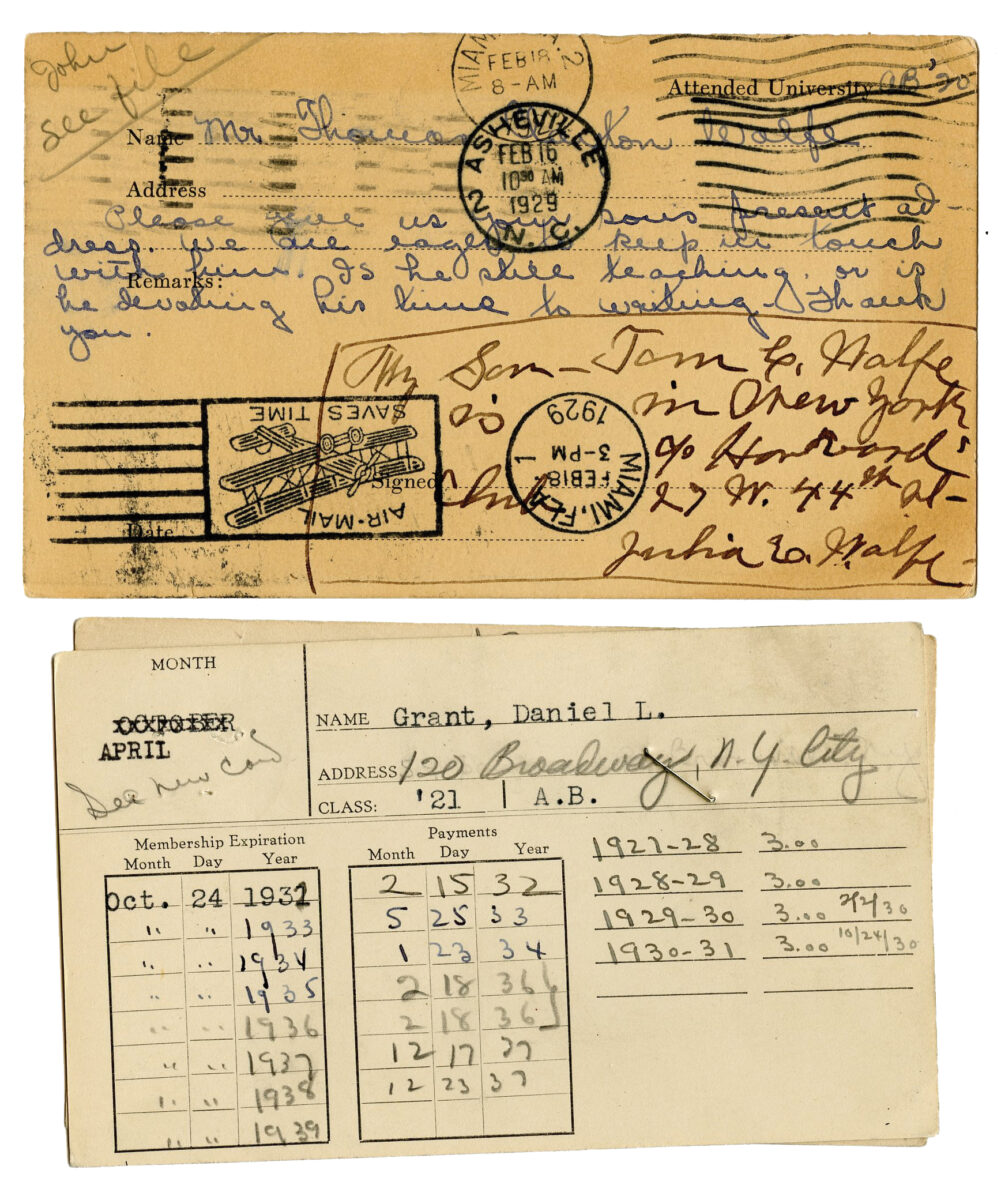

The GAA used to keep track of alumni via postcards like these. The one at the top was returned to the association in February 1929 by Julia Wolfe, the mother of novelist Thomas Wolfe (class of 1920). Julia reported that Thomas was taking his mail at New York’s Harvard Club. The postcard on the bottom is from our file folder for former GAA secretary Daniel Lindsay Grant (class of 1921). It shows that over the years he consistently paid his $3.00 membership dues (equivalent to roughly $52 in 2022). Today, the GAA’s online database allows our records department to track membership statistics and a whole lot more.

In 2013, the Database for Advancing our Vision of Institutional Excellence, or DAVIE, was launched. It is still used today.

Starting in 1997, alumni directories were published every five years or so, and a CD-ROM version was added. The directory is only as accurate as alumni make it. The process for collecting updates can take up to six months. “The print directory is a snapshot of one particular day,” Nelsen said. “It’s out of date the moment we say we aren’t taking any more updates.” In 2000, the entire directory was placed online.

Records staff also field phone calls and answer mail from people who, for example, have found a class ring and are trying to track down its owner, or from family members of a deceased alumnus curious about their loved one’s early life.

“We help alumni stay connected to each other and to the University,” Nelsen said.

— Nancy E. Oates