One-Man Crew

Morehead Scholar Ed Perkins ’09 says he’s not particularly creative, but Carolina freed him to become an award-winning, do-it-all documentarian.

By Paul Wachter

When Ed Perkins ’09 first visited UNC in 2005 as a perspective Morehead Scholar from England, he was struck by how the University’s presence loomed over every facet of Chapel Hill. He had previously toured several American universities in the Northeast, but even Harvard and Yale hadn’t left him quite as gobsmacked.

Perkins visited Kenan Stadium, looked up at the tens of thousands of empty seats “and was blown away,” he recalled. Even the McDonald’s on Franklin Street left an impression. “McDonald’s are red inside, but I went inside, and everything was Carolina blue,” Perkins said. “And I remember thinking this university must really be something if even a major corporation like McDonald’s changes its colors.”

Perkins was eventually awarded a Morehead Scholarship, now the Morehead-Cain Scholarship. When he arrived on campus that fall and entered his dorm room, he immediately experienced culture shock — “in a good way,” he said.

“I met my roommate, who was a guy named Elvis,” Perkins said. “He was wearing boots and a cowboy hat. It was this pinch-me moment, like in a movie, but this was actually real.”

Perkins has been pinching himself ever since. He recently recounted his first impressions of Chapel Hill in a Zoom conversation from his home in London, which he shares with his wife and child. He was in the middle of a publicity campaign for his third documentary feature film, The Princess, which debuted on HBO in August. The documentary explores the public life of Diana, Princess of Wales, who died 25 years ago but still holds a firm place in popular culture.

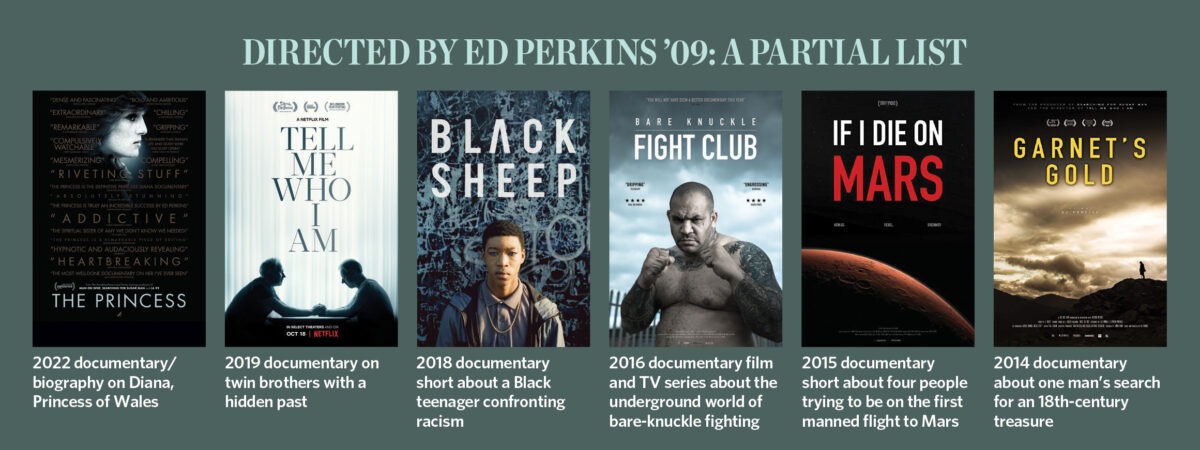

Perkins’ two earlier features and various short films showcased emotional stories about relatively unknown figures and have won numerous awards — including an Oscar nomination for the documentary short Black Sheep, depicting one person’s experience in an English housing project.

Perkins majored in political science, and it was during only his last two years at UNC that he began working in film, principally under Gorham “Hap” Kindem, professor emeritus of media studies and production. Kindem sees a distinctive voice that permeates both Perkins’ unpolished student work and his professional oeuvre. “What you see is his process of storytelling and discovery,” he said. “There’s a way of revealing things that allows the viewer the opportunity of discovery without an overreliance on interviews or narration.”

Ed Perkins ’09 at his home in Winchester, England. “One of my earliest emotional memories was wishing I was American, growing up with a white picket fence. … My dad came out [to UNC] when I started as a freshman, and there was an orientation ceremony at the Dean Dome with a marching band and cheerleaders,” Perkins said. “It was a bit of a shock for him in the best way. And it felt liberating for me to be thrown into this whole new world.” PHOTO: AP Images/Fiona Hanson

A lightbulb

The oldest of four siblings, Perkins grew up in Hampshire, a county in South England, where his father worked as a software engineer and his mother as a teacher. Ed was studious and attended the prestigious boarding school Marlborough College, whose graduates include Kate Middleton, the current Princess of Wales.

He was accepted at his father’s alma mater, Oxford University, with intentions of studying politics, philosophy and economics and thoughts of a career in finance or engineering. But he bristled at the path that was laid before him, not necessarily by his parents or teachers, but by the imperious forces of a prestigious English education. “I felt slightly that I was being funneled,” Perkins said. “My career choices seemed to be narrowing. I’m not naturally rebellious, but I was keen to do something different and get off that track.”

So Perkins began considering universities in the United States. “One of my earliest emotional memories was wishing I was American, growing up with a white picket fence,” he said. He considered Ivy League schools and a few other colleges, but then he came across what he remembers to be a black-and-white photocopy of a leaflet about the Morehead Scholarship in his school’s careers department.

Vanity Fair travel journalist Michelle Jana Chan ’96, a Morehead Scholar who had also attended Marlborough College, encouraged Perkins to apply. When he won a scholarship, it was an easy decision to accept.

“My dad came out when I started as a freshman, and there was an orientation ceremony at the Dean Dome with a marching band and cheerleaders,” Perkins said. “It was a bit of a shock for him in the best way. And it felt liberating for me to be thrown into this whole new world.”

By the end of his sophomore year, Perkins had almost completed the requirements for his political science major, giving him the time and space to enroll in a range of courses — a vastly different experience from a typical British education in which university students focus on one subject. Perkins said he felt his dreams broaden when he was free to take Spanish, French and European history classes.

Perkins said he didn’t consider himself a creative person and professed no aptitude for drawing or music. But he had a passing interest in photography and film and enrolled in a film class. “It was an amazing moment, making short films with a camera,” Perkins said. “A lightbulb went off. It was the first time in my life that I had found a genuine creative outlet.”

Carolina didn’t have a film school, and still doesn’t, but it offered several classes in the communications department, including courses in film theory and technical production. (The English and comparative literature department now offers a film studies concentration.) Perkins signed up for some classes and forged a close bond with Kindem.

Kindem showed his students films that were stylistically innovative, such as Errol Morris’ documentary The Thin Blue Line, about a Texas murder trial, which was controversial for its liberal use of reenactment when it debuted in 1998. “Students were trying to master the technical side of filmmaking and figure out what they have a passion about,” Kindem said. “The last part to grasp is style, something unique to them. And I think Ed already was developing a style.”

At Carolina, Perkins filmed numerous documentary shorts — including, in his words, “an awful production video for our club rugby team” — and dabbled in filming drama. For his honors thesis, typically a long paper, Perkins received permission to shoot a documentary about religion, based on his summer travels to India and other countries. It focused on the conflict between religious believers and the New Atheists, intellectual brawlers including Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens. (Hitchens, who died in 2011, appears in Perkins’s student documentary and The Princess.) “I made lots of filmmaking mistakes, but it was a great experience,” Perkins said.

Back to London

The Morehead-Cain alumni network is wide, and as he finished his senior year, Perkins reached out to Kim Woodard ’96, who had enrolled as a Morehead and then became executive producer of National Geographic Television in New York. She offered him a summer internship. “From week one, everyone was aware that this was a young person that had so much talent to give,” said Woodard, who now runs the unscripted production company Lucky 8, along with several partners.

Perkins was sent across the country to film “sizzle reels,” mini-films used to fundraise for feature-length documentaries. National Geographic assigned him to find characters, create proposals for new projects and outline what the shows would be about. “He excelled at everything,” Woodard said.

At the end of the summer, Perkins was offered a full-time job. Woodard recalled two projects he worked on the following year: one on the Hasidic community in New York and the other about amateur wrestling in New Jersey. While many former interns were glued to their computers searching for characters, Perkins went out into the world, Woodard said. “Ed was building relationships with a young wife in a Hasidic community and an older Hasidic scholar, while also spending time with a first-year amateur wrestler in New Jersey,” she said.

Perkins’ visa ran out a year into the job, however, forcing him back to the United Kingdom, “which wasn’t what I wanted to do at the time,” he said. In London, he reunited with James Dean ’89, a fellow English Morehead alumnus, who had recommended Perkins for the fellowship and happened to work in scripted film and television production. Dean hired Perkins for a couple of small projects and also arranged for him to do some promotional work for The Eagle, a 2011 historical drama, filmed in Hungary, about a Roman officer that starred Channing Tatum. It was directed by Dean’s friend, Kevin Macdonald, who also directed the Oscar-winning 1999 documentary One Day in September.

Dean also introduced Perkins to Simon Chinn, who produced the Oscar-winning documentary Man on Wire, about the French daredevil Philippe Petit, who famously balanced on a wire strung between the World Trade Center’s twin towers. “I had watched it during my final year at UNC, and it blew me away,” Perkins said. “It did for me emotionally what the best drama films did, and I hadn’t yet seen a documentary that had moved me in that way. I told myself, ‘I’d like to try one day to make that kind of film.’ ”

Chinn hired Perkins to shoot behind-the-scenes documentaries of the feature films he was producing, including the critically acclaimed Project Nim and Searching for Sugar Man, the latter of which won the 2013 Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature Film.

Meanwhile, Perkins was working on his own project. “When I’d meet up with Ed in London, he was always carrying camera bags and tripods, like a one-man crew,” Dean said. “He obviously was, after our coffee or beer, going to head out and visit this man he had told me about, who was looking for a pot of gold at the end of a Scottish rainbow.”

Tell Me Who I Am, Perkins’ second feature, is the true story of twin brothers Alex and Marcus Lucas. At 18, Alex loses his memory in an automobile accident, leaving it to his twin to fill him in on his childhood. But Marcus chooses to shield Alex from a horrid truth. Photo: AP Images/Fiona Hanson

A calling card

In Garnet’s Gold, Perkins’ first feature film, viewers meet Garnet Frost, an eccentric Englishman in his late 50s, who lives with his ailing but doting mother. About 20 years earlier, Frost was hiking in the Scottish Highlands and discovered a staff, which later he comes to believe is a clue to the location of a treasure lost in the 1700s that was bound for Prince Charles Edward Stuart, part of the exiled Stuart monarchy who launched a failed campaign from Scotland to retake the throne. Obsessed, and with no conventional job to hold him back, Frost borrows money from his mother to rent a car and sets off to Scotland with Perkins, who had by then spent many long hours with Frost in London.

The quixotic search, while featuring gorgeous shots of the Highlands, isn’t the point, but rather it serves more as a metaphor for Frost’s aimless life, filled with both small joys and existential regrets. Neither Frost nor his mother is as goofy as the mother-daughter protagonists (both named Edie Beale) of the seminal 1975 documentary Grey Gardens, and Perkins’s aim is not to dwell on Frost’s eccentricities but rather to provide a full, empathetic view of middle-age ambiguities.

“I took a look at a cut he had made and said there’s got to be a film here,” Chinn said. “I felt I had to be involved in Ed’s career, which was slightly self-serving, if I’m being totally honest. I knew he could help grow my young company.”

Garnet’s Gold debuted at the Tribeca Film Festival in 2014 and won awards at other festivals worldwide. Perkins was named best newcomer by the Grierson Trust, which gives out Britain’s most prestigious documentary awards. “Garnet’s Gold in a way was a very uncommercial film, but it was an amazing calling card for Ed given how he made it,” Chinn said. “Fundamentally, he made it on his own. At the very end, we brought on an editor and composer, but it was essentially a solo project.”

For Perkins, it was a vindication of his unconventional career choice. “It took me about five years to make,” he said. “The Tribeca premiere felt like a real moment — proof positive that if you just got a camera and had a great story, you didn’t need a big budget or big crews.”

As the producer, Chinn partnered on Garnet’s Gold with BBC Storyville, the documentary division of the British news service, and where Kate Townsend was the commissioning editor. “I already felt Ed was a distinctive, emerging filmmaker,” she said. In 2017, Townsend left the BBC for Netflix, where she secured the rights to Perkins’ second feature, Tell Me Who I Am.

The feature is a captivating, disturbing true story of twin brothers Alex and Marcus Lucas. At 18, Alex loses his memory in an automobile accident, leaving it to his twin to fill him in on his childhood. But Marcus chooses to shield Alex from the horrid truth — that their mother and her friends sexually abused the young boys — and paints a happier, more conventional image of their youth. The twins wrote a book of the same name that was published in 2013.

About two years later, Perkins saw a news article about the brothers’ story, and approached Chinn with the idea. “I loved the story, but I was nervous about plunging into it,” Chinn said. “Because Ed was quite young and it needed incredibly careful handling. We were all nervous about it, including the subjects. Mostly the subjects.” There were a couple of other projects Chinn and Perkins were working on, so they extended the options for the rights to the story for several years.

During the interlude between his first and second features, Perkins shot Black Sheep. The young protagonist of the film, Cornelius Walker, reached out to Perkins because he was interested in being a filmmaker. Over coffee, Walker told his story: a Black kid living in a working-class, predominantly white housing project, who ultimately, to fit in, adopted similar anti-Black prejudices held by his white peers. The 27-minute film premiered on The Guardian, and Walker subsequently began his own directing career.

Documentary canon

AWARDS AND NOMINATIONS

Tell Me Who I Am: 2020: nominee, Grierson Award for Best Single Documentary, Grierson Trust British Documentary Award. 2019: nominee, Best Documentary, British Independent Film Award.

Black Sheep: 2019: winner, Best Documentary Short, Irvine International Film Festival; nominee, Best Documentary Short Subject, Academy Awards; nominee, Grierson Award for Best Documentary Short, Grierson Trust British Documentary Award. 2018: winner, Northern Film School Award for Best Screenplay; winner, Festival Prize, Aesthetica Short Film Festival; nominee, Camden Cartel Award for Best Short Film, Camden International Film Festival; winner, Candidate for the European Film Award, Cork International Film Festival; winner, Sheffield Short Doc Award and International Competition, Sheffield International Documentary Festival; winner, Jury Award, Audience Award, and Students’ Award, Best Film, This is England Film Festival Rouen; nominee, Best Short Documentary, Hot Docs Canadian International Documentary Festival; nominee, IDA Award for Best Short, International Documentary Association.

2017: winner, Jury Award, Best Short Documentary, Dallas Video Festival.

Garnet’s Gold: 2015: winner, Best Newcomer Award, Grierson Trust British Documentary Award; winner, Award of Excellence Special Mention for Documentary Feature, IndieFEST Film Awards; winner, Jury Award, Best International Documentary, Docville; nominee, Best International Documentary, American Documentary Film Festival and Film Fund; winner, Festival Prize for Best Documentary (International), Jozi Film Festival; winner, Gold Panda for Best Photography International Documentary, Sichuan TV Festival; nominee, Festival Prize for Best Documentary (International), London Independent Film Festival; nominee, Biogram Film Award for Best International Documentary, Biografilm Festival.

2014: nominee, Jury Award for Best Documentary Feature, Tribeca Film Festival; nominee, Best Documentary Feature Film, Edinburgh International Film Festival.

Garnet’s Gold is a so-called observational documentary. Perkins and his camera followed Frost into his home, local pub and Scottish countryside. Aside from a few reenactments (excluding, of course, the sexual abuse), Tell Me Who I Am unfolds in a dark studio, with the brothers taking turns speaking to the camera and in the final act talking to each other. Stylistically, it recalls Errol Morris’ interrogation of former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld in The Known Unknown — though Perkins’ voice, unlike Morris’, never appears in the film. (For the interviews, Perkins, like Morris, used an Interrotron, a camera setup where the interviewee looks directly at the documentarian rather than focusing on the camera lens.)

“At the end of Tell Me Who I Am, there’s that extraordinary moment where Marcus finally tells his brother the truth of what had happened to them as kids,” Perkins said. “It’s totally unedited.”

To get to that moment, Perkins spent many months with the twins off-camera. “So much of what we do as filmmakers is getting permission from people,” Perkins said. “I told Alex and Marcus, ‘At some point, we have to talk about this really difficult thing that you haven’t spoken about. Are you okay with that?’ And they said, ‘You need to ask us to speak about it.’ ”

To establish this intimacy and thoughtfulness on camera, Perkins relied on several techniques. For most documentaries, filmmakers typically have only a few hours to interview their subjects on camera. But Perkins filmed seven days of interviews. Creating the dark studio interview space also was purposeful. “If you want someone to reveal something emotionally complicated, you might think you should talk at a place where they feel comfortable, like their house,” Perkins said. “But an uncomfortable space can create intensity.”

The goal isn’t to manipulate but to inspire introspection. “I’m trying to take the person on a journey to explore that ambiguity,” Perkins said. “Not to catch them out or make them feel bad about anything — the opposite. To embrace the complexity of real life. When you have people struggling to work things out in real-time, I find it incredibly captivating.”

Journalist Peter Savodnik, who has collaborated with Perkins on several short films, said a key to Perkins’ success as a filmmaker is his demeanor off- and on-camera. “I’ve worked with many documentarians, and with Ed, how he acts on camera you can tell it’s not a put-on,” Savodnik said. “With a lot of filmmakers, there’s a dramatic difference in their tone on- and off-set, while Ed doesn’t toggle his personality. You feel that, and it deepens the empathy with his subjects.”

Tell Me Who I Am premiered at the 2019 Telluride Film Festival in Colorado and was nominated for several awards. “It’s become a real reference point for emerging filmmakers,” Netflix’s Townsend said. “I get pitched treatments and outlines that use it as a reference in terms of tone and style. Ed has become part of the documentary canon.”

The drama space

Perkins’ latest documentary, The Princess, represents another stylistic shift. The film relies completely on archival material, a choice that now seems prescient as the documentary was made during the COVID-19 pandemic, when many film productions were suspended over health concerns.

Diana is hardly an uncovered subject. The Princess, following in the wake of Netflix’s The Crown and other recent productions about the Royal Family, “may sound like one Diana documentary too many,” noted Variety. “Yet after all those dramatic treatments, it’s galvanizing to see the real story laid out exactly as it happened — or, more precisely, as it happened and as it was presented to the public, those being, quite often, two very different things.”

Perkins can vividly recall his mom awakening him with the news of Diana’s death in 1997. “I was 11 or 12,” he said. “There was this outpouring of grief. Grown men and women crying on the streets. The reason for making the film was trying to find out how and why we all reacted in the way we did. We’re not trying to uncover who Diana was. We’re trying to uncover what her story says about us.”

Older than Perkins and with stronger memories of Diana, Dean said he admired the film’s approach to her life. “It was handled so skillfully, just showing without being told what to think,” he said. “Obviously it’s subjective, and choices are made about scenes to include and exclude, but there’s space for one to think for oneself.” Dean said Ed’s approach in The Princess reminded him of Asif Kapadia’s Amy, a documentary about the late singer Amy Winehouse, which unearthed a lot of unseen footage and won the 2015 Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.

Late last fall, Perkins was still handling publicity for The Princess while working on a few projects for Lightbox, the production company Chinn founded with his brother Jonathan, and for which Perkins is the only full-time director. He has yet to begin his next feature. “We’re working on some really interesting ideas, but we have a high bar for stories,” Perkins said.

Perkins said he’d like to make a fiction feature film, which several notable documentarians have done, including James Marsh (The Theory of Everything), Kevin Macdonald (The Mauritanian), and Werner Herzog (Aguirre, the Wrath of God and Fitzcarraldo). “I seem to spend a lot of time making my documentaries feel like dramas, and instinctively, if I got the chance to do drama, I think I’d try to make them feel like documentaries,” Perkins said.

“I’m excited to see what he does next,” Townsend said. “The natural progression may be to explore the drama space, but I hope he always keeps making documentaries.”

Paul Wachter has written for The New York Times Magazine, Harper’s Magazine, ESPN and The Atlantic. He lives in Chapel Hill.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.