Out of Anger, Frustration — Hope

Posted on Sept. 15, 2023

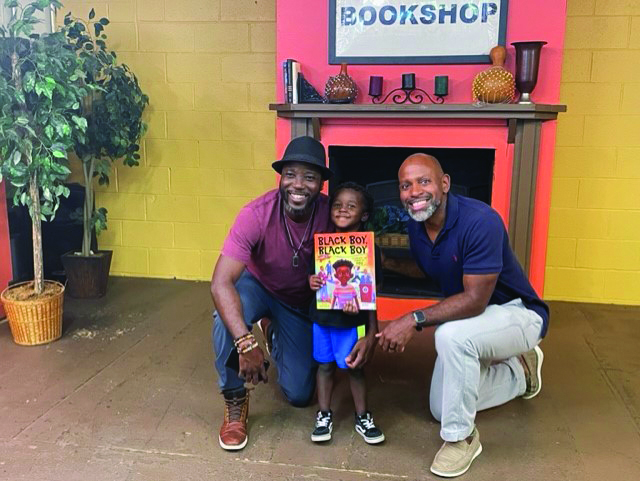

Ali Kamanda ’00 (left) and Jorge Redmond ’00 wrote a book to inspire Black boys. (Photo: Jorge Redmond ’00)

The students filing into the library at Carrington Middle School in Durham weren’t sure what to expect as they took their seats on a bright February morning. Most of them had never met a published author before, let alone attended a public reading and book discussion.

For the next 45 minutes, they listened intently as Jorge Redmond ’00 and Ali Biko Sulaiman Kamanda ’00 delivered a joyful, theatrical reading of Black Boy, Black Boy: Celebrate the Power of You, the children’s book they created in 2020 and published last year, with vibrant illustrations by Ken Daley.

“We wrote this for our boys, and for all of you,” Kamanda said. “We wanted to inspire you to believe in yourselves.”

Composed in the same rhyming cadence as the classic Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? — the classic 1967 children’s book written and illustrated by Bill Martin Jr. and Eric Carle — Redmond and Kamanda’s book introduces younger students to Black men who were pioneers in science, aviation, politics and culture. There are names that almost every school kid knows — Barack Obama, Colin Kaepernick, Martin Luther King Jr. — alongside historical figures that most students have never encountered: Elijah McCoy, an engineer and inventor who earned more than 50 patents for his work with steam engines; William Goines, the first Black man to qualify as a U.S. Navy SEAL; and Arthur Mitchell, an acclaimed ballet dancer and choreographer.

The school reading, organized by Carolina Public Humanities, was attended by mostly Black and Hispanic middle schoolers wearing hoodies, pajama pants, Crocs and sweatshirts. Many of them began leaning forward in their chairs as the authors told the story behind the book. Redmond and Kamanda told the kids how they met at Carolina, became lifelong friends and decided to branch out from their day jobs to become children’s book authors. Redmond is an assistant district attorney in Asheville, and Kamanda is a filmmaker and the president of Salone Rising, a nonprofit that supports small businesses in Sierra Leone.

After attending Carolina, the two men stayed in touch even as their lives went in different directions. Kamanda, who emigrated from Sierra Leone as a teenager, splits his time between Pennsylvania and West Africa. Redmond grew up in Asheville and has been a public prosecutor there since 2017.

“I’m very proud of this,” Kamanda said, holding the book aloft for the students to see. “I think it helps young people believe they have the capacity to do anything they want in the world.”

The message of hope and agency came out of a moment of despair and frustration for Redmond and Kamanda. In summer 2020, as some of the largest protests in modern American history erupted in response to the murder of George Floyd by a white Minneapolis police officer, Redmond and Kamanda found themselves venting their anger and frustration during long phone calls to each other. Both men have Black sons, and the widespread fear and outrage in the aftermath of Floyd’s killing felt urgent and personal. “We need to actually create something, to inspire,” Kamanda recounted during a public discussion at Chapel Hill’s Flyleaf books, the same day as the Durham classroom visit. “How can we transform this anger and pain into something hopeful?”

“I was hearing such limited visions of success for Black boys. … There are Black men who did extraordinary things who are also hidden. If we tell these boys about their past, it will help shape their future.” — Jorge Redmond ’00

For Redmond, a book of inspirational figures made sense after years of seeing young men come through the criminal justice system with few reasonable ambitions for adult life and no realistic sense of what’s possible for Black men in America. “I was hearing such limited visions of success for Black boys,” Redmond said. “They didn’t have goals outside of being an athlete or a rapper. They’re seeing rappers, entertainers — and George Floyd.”

Redmond and Kamanda wanted to offer a more tangible sense of hope to their sons and others like them. “There are Black men who did extraordinary things who are also hidden,” Redmond said. “If we tell these boys about their past, it will help shape their future.”

That goal is now widely shared in the publishing industry. Nationwide, the percentage of children’s books featuring Black or Hispanic main characters has increased in recent years, part of a movement for more representation of America’s diversity in books, movies and school curricula. The percentage of children’s books by Black authors more than doubled between 2019 and 2022, according to research by the University of Wisconsin released this year.

Redmond and Kamanda wanted to offer a more tangible sense of hope to their sons and others like them. (Photo: Jorge Redmond ’00)

The result is on vivid display in the Carrington Middle School library, where media coordinator Vanessa Calhoun ’97 presides over a space that looks more like an independent bookstore than a traditional school media center. The shelves are organized into kid-friendly genres. Section headings include Relationships, Powerful People, Resist & Persist and Cook It!, with biographies of Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman elected to Congress, blues singer and musician Muddy Waters and ceramic artist Maria Martinez. Calhoun was thrilled to host two charismatic Black authors with a local connection. “Our school is extremely diverse, and I want my students to know there’s more out there than what they might have seen in their lives,” she said. “Everyone deserves to be seen and know they’re integral to our world.”

The language in Black Boy, Black Boy is carefully chosen to convey the message of belonging in the plainest terms. On a page that depicts a Black father speaking warmly to his young son, the text reads, “With joy and love, this is written for you. Believe in yourself and all you can do.” At their Flyleaf talk, Redmond and Kamanda discussed the importance of cultivating agency in young people and building confidence by showcasing examples of success.

Both men credited their time at Carolina for opening a sense of possibility about the world and helping focus their ambitions. Kamanda found mentors who nurtured his interest in screenwriting and filmmaking. Redmond recalled the hard but meaningful experience of being dropped from the varsity soccer team after his grades dipped. By the time he graduated, he’d climbed from academic probation to the dean’s list.

“We came to this place as young minds, ready to take on the world but not really knowing what the world was,” Kamanda said. “It’s sweet to be back.”

At Carrington, when the men finished their reading and opened the floor to student questions, one of the first was from a girl who wanted to know why their book focused on boys. Redmond laughed. “My daughter asked me the same thing,” he said, explaining that Black Boy, Black Boy would not be their last book. He and Kamanda are already hard at work on Black Girl, Black Girl, and they promised they’d be back to read it soon.

— Eric Johnson ’08

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.