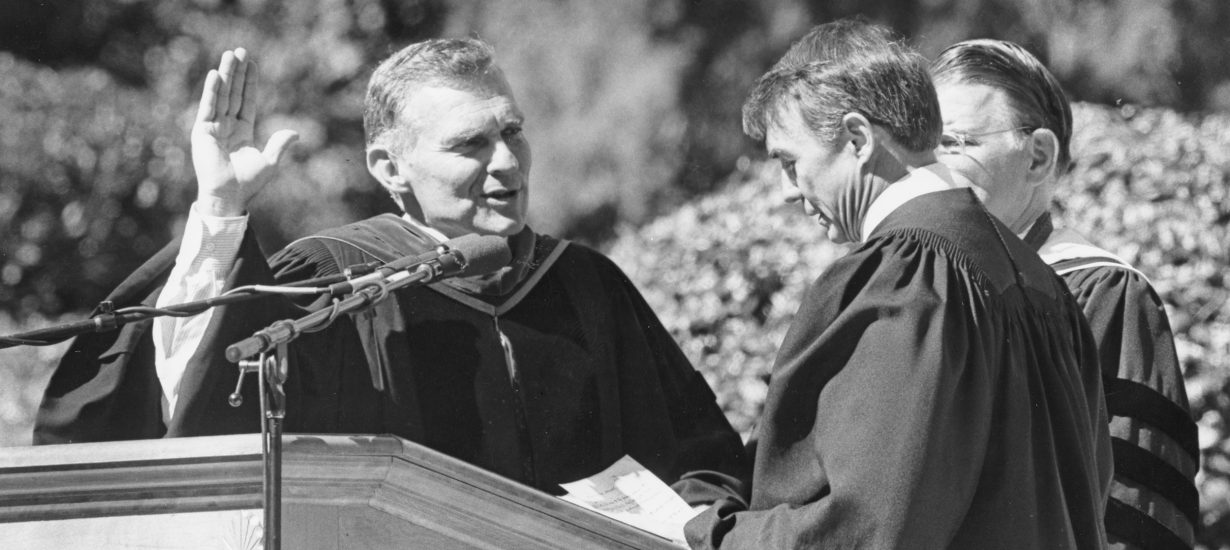

Friends, University Bid Farewell to Paul Hardin, University’s ‘Bicentennial Chancellor’

Paul Hardin III, the steadfast lawyer and Methodist bishop’s son who steered UNC and three other campuses as they grew through tumultuous and historic times, has died. He was 86.

Hardin spent 27 years as a leader in higher education — the final seven of those at the nation’s oldest state university under the sentimental glow of its bicentennial.

Hardin, who said in a 2014 speech before a small charity event that he had been diagnosed with ALS the year before, died at his home Saturday. He lived in Carolina Meadows in Chapel Hill with his wife of 63 years, Barbara.

His administration was highlighted by the triumph of the University’s yearlong bicentennial celebration and by the often-fiery campus debate that eventually birthed the Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History nearly a decade after he left office.

“Chancellor Paul Hardin was a visionary leader who is remembered in North Carolina and across our nation for his dedication to promoting the life-changing impact and benefits of higher education,” Chancellor Carol L. Folt said. “In his bicentennial address, alumnus Charles Kuralt [’55] spoke of how Carolina was meant to be ‘the University of the people.’ Paul seized upon Carolina’s 200th birthday as an opportunity to light the way to a better future and open Carolina’s doors for all North Carolinians. Paul was warm and gracious and remained very involved with Carolina after his retirement. He will be greatly missed.”

On paper, Hardin was an unlikely choice to become Carolina’s seventh chancellor. He was a 1952 Phi Beta Kappa graduate of Duke University, where he was on the golf team, earned a law degree and served on the law school faculty for 10 years. When told of Chapel Hill’s interest in him, Hardin, then the president of the 2,400-student Drew University in New Jersey, was incredulous. He twice turned down the offer to apply, believing it a doomed proposition.

He was convinced to send a resume in the late winter of 1988, and by April, Hardin was a Duke man no more. He was Carolina’s man.

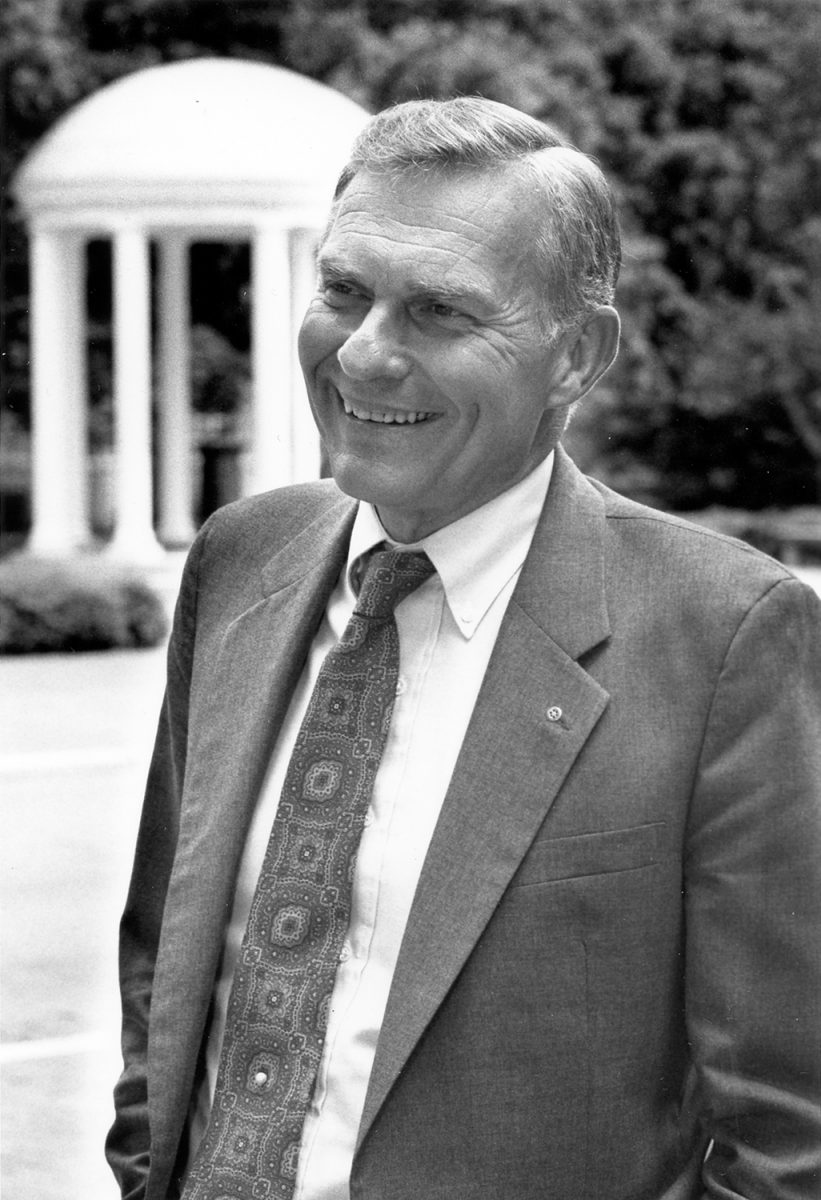

Chancellor Paul Hardin, pictured in 1989, said in an oral history: “I had the privilege of becoming a sentimental, outspoken supporter, an awestruck admirer and an advocate for this University.”

“There was never any doubt but that I was brought here to be the bicentennial chancellor,” he said. He was hired to prepare Carolina to start its third century, first by spearheading an initial $300 million capital campaign, the largest in school history. He did so with gusto. As he crisscrossed the state and country, he unabashedly needled supporters to turn out their deep pockets. In the end, the campaign raised an extraordinary $440 million.

It was the Bicentennial Observance, which culminated in a Kenan Stadium gala on Oct. 12, 1993, attended by then-President Bill Clinton and infused with Kuralt’s resonance, that was the most joyous for Hardin, the most cementing of his love for the place he came to call “my university.”

“I had the privilege of becoming a sentimental, outspoken supporter, an awestruck admirer and an advocate for this University,” he said in an oral history.

Great turbulence hovered among many triumphs. An unexpected political storm broke out at Carolina in 1992 after Hardin refused student demands for a freestanding Black Cultural Center, instead calling for an expansion of the inadequate space the BCC occupied in the Student Union. The announcement triggered a period that Hardin called the “greatest personal anguish” of his career.

All his life, Hardin had considered himself a progressive liberal who worked to promote women, minorities and differing opinions on campuses and in his administrations; indeed minority faculty numbers doubled at Carolina under his tenure.

Hardin had run for mayor of Durham, where he was active in civil rights issues, in 1967 and lost in part due to his liberal views on race relations.

In the BCC battle almost three decades later, the chancellor worried that a freestanding center would promote separatism. But student supporters of a dedicated building believed he was degrading the importance of black culture on campus and stalling progress.

Hardin’s statement, “We want a forum, not a fortress,” galvanized proponents for a freestanding center to lead the largest demonstration movement on campus since Vietnam. Sixteen people were arrested after marching into the chancellor’s office in April 1993. The controversy drew national attention from the media as filmmaker Spike Lee and the Rev. Jesse L. Jackson visited campus to lend their support.

News cameras captured placards that read “Hardin’s Plantation,” but not the truth that Hardin felt inside — that he was in a lose-lose situation. BCC supporters saw him as against the center’s existence, while conservative opponents of a BCC called him a champion.

“What’s broken my heart is that I’ve been portrayed as a ’60s liberal who stopped growing,” Hardin told Newsweek in October 1992. Earlier in his administration, he had convened a special committee to study the campus atmosphere for minority groups, including blacks. “I believe in the legitimacy of a black-culture center,” he said. “I’m not an opponent.”

The controversy cooled in July 1993 when a planning committee appointed by Hardin — minus student protesters, who refused to participate — recommended a freestanding center for the BCC. Hardin won what he considered the salient point in the debate: that the center would be a working classroom building under the auspices of the provost, not a separate union under the department of student affairs. The Stone Center opened in a 44,500-square-foot building in Coker Woods in 2004.

Hardin also tangled with the rules and rule-makers who hovered outside the stone walls and had the power to prevent the kind of progress he desired. When he was installed at UNC, he experienced what he called “culture shock” after two decades of presidencies at private, Methodist-related colleges. He never had steered an institution quite like Carolina: a major public research university with voluminous working parts and complicated gear — and with a state government ever looking over its shoulder.

He pushed for a $310 million construction bond referendum, grew research grants by $156 million and raised a disagreeable voice right up until the final weeks of his tenure, when he scolded Gov. James B. Hunt Jr. ’64 (LLBJD) and his 1995 budget proposal for its deep cuts to the campus with the warning, “Don’t play political chicken with my university.”

“He has been the first to jump to the defense of the University faculty, students and staff when he believed they were being shortchanged,” Hunt told the University Gazette when Hardin retired, “facing down everyone from the state legislature to the governor to accomplish what he believes in.”

Hardin’s determination became known to the greater higher education community during his tenure at Southern Methodist University from 1972 to ’74. Hardin discovered payments were being made by boosters and trustees to Mustang football players for good plays; he reported it to the NCAA, relieved Coach Dave Smith of his athletic director duties and shortened Smith’s four-year football contract to one season.

Hardin’s honesty cost him his job when SMU’s board asked for his resignation.

He came by his fighting spirit honestly. Born in 1931 in Charlotte, his family lived in towns across North Carolina, moving every few years with his father to a new church. Competitiveness was in him and all around him: His father bet him $5 when he was 8 years old that he could not beat him on the links; he finally did when he was 19.

And at Duke, where he was on the varsity golf team, he laid down the terms of his participation during his first year of law school, when he still had a year remaining of college sports eligibility. Hardin told his coach that he would not compete at the conference tournament because it was played too close to his final law exams and he did not wish to be distracted; he intended to finish first in his class. And so he did.

Hardin married fellow Methodist preacher’s child Barbara Russell the day after his law school commencement, and then the High Point High School graduate spent two years in the U.S. Army Counterintelligence Corps, crawling “through steam tunnels in the Pentagon to make sure the area was secure.” When he re-entered civilian life, he worked as a trial lawyer in Birmingham before Duke asked him to return to the law school, where at 32 he became its youngest full professor.

Hardin was hired from Duke in 1968 at age 37 to be president of Wofford College, his father’s and grandfather’s alma mater, without having held so much as a committee chair while on the faculty in Durham. He stayed four years, using his relative youth to relate to a student body made restless by the political times — and caught the attention, however ill-fated, of Southern Methodist in 1972.

He landed at Drew University after his ouster in Dallas; there, he built a reputation in the sciences for the small liberal arts campus. In 1983, long before it became vogue to do so, Drew put a personal computer on the desk of every student.

Hardin received the 1995 N.C. Public Service Award from Gov. Hunt; the Distinguished Service Medal from the UNC General Alumni Association in 2003; and the William Richardson Davie Award from by the UNC Board of Trustees in 2004, the highest honor given by the board.

Following retirement, Hardin served one year as interim chancellor at the University of Alabama-Birmingham, was emeritus professor at Carolina’s law school, and spent time with his wife, three children and his grandchildren.

In March 2007, Morrison South Residence Hall was renamed Paul Hardin Hall. Hardin and his wife joined with then-Chancellor James Moeser and Chancellor Emeritus William Aycock ’37 (MA, ’48 JD) and former Interim Chancellor William McCoy ’55 for the hall’s dedication.

Also on hand was Dick Richardson, a retired provost and political science professor who chaired the Bicentennial Observance while Hardin was chancellor.

Richardson said the essential quality of leadership Hardin possessed was his great comfort being himself. There is no veneer to him. No pretense, no façade of personality to hide the real person, Richardson said.

“If you scratch deeply beneath the surface of Paul Hardin, you will find exactly what you find on the surface, for this man is solid oak from top to bottom,” Richardson said.

— Beth McNichol ’95

This story includes reporting from UNC.edu

Updated July 11:

A memorial service was held at 3 p.m. Saturday, July 8, at University United Methodist Church in Chapel Hill. In lieu of flowers, the family suggested gifts may be made to The Robert and Martha Gillikin Library Fund in honor of Paul and Barbara Hardin at the UNC Libraries, the Duke University ALS Clinic, the Paul Hardin Scholarship Fund at the Duke Law School or the Hardin-Russell Endowment Fund at Lake Junaluska Assembly.

View an excerpt of the memorial to hear Russ Hardin eulogize his father.

The University rang the South Building bell seven times on the day of Hardin’s memorial service to honor his role in UNC history as the seventh chancellor. The ringing of the bell is used to mark only the most significant University occasions.

More Online

- Paul Hardin was UNC’s seventh chancellor, serving from 1988 to 1995.

- More about the history of the chancellorship is available online in the Review’s “History of the Chancellorship” series.